Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

“Be quiet and calm, my countrymen, for what is taking place now is exactly what you came to do. You are going to die, but that is what you came to do. Brothers, we are drilling the drill of death. I, a Xhosa, say you are all my brothers, Zulu, Swazis, Pondos, Basutos, we die like brothers, for though, they made us leave our weapons at home, our voices are left with your bodies.”

In February 1917, another First World War centenary commemoration will be held. The 21st February 2017 marks the centenary of the tragic loss of 625 lives when the SS Mendi, a troop ship carrying over 800 members of the South African Native Labour Contingent, officers and crew, sank in tragic circumstances off the Isle of Wight in the English Channel. The ship departed from Southampton on the 20th February and the men having made the long voyage from Cape Town were on the final leg of the journey to take them to France to work as labourers in support of the British Empire war effort. 616 of the men who lost their lives were part of the 823 South African non-combatant servicemen (or labouring members) of the 5th Battalion.

The Mendi sank in less than half an hour when another British ship, the SS Darro, a much larger vessel, smashed into the Mendi with such force that a gash opened from keel to deck to a depth of about 20 feet. There was thick fog and no lights showing, the weather was cold and the water icy. The sinking of the Mendi has become part of our oral history of heroism and bravery in death. The men were said to have removed their boots on the deck and performed the death dance. The Reverend Isaac Wauchope Dyobha’s speech – ‘We die like brothers’ in these final moments became a speech of pride, and an impassioned plea for a united black national identity. In 2003 a new honour primarily for civilian bravery (in three classes, gold, silver and bronze) was instituted by the South African government (Order of Mendi).

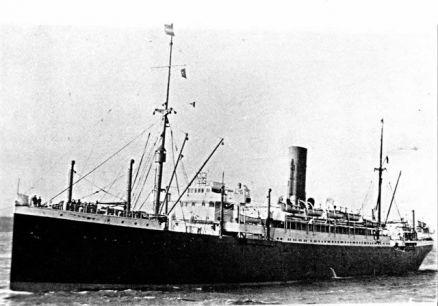

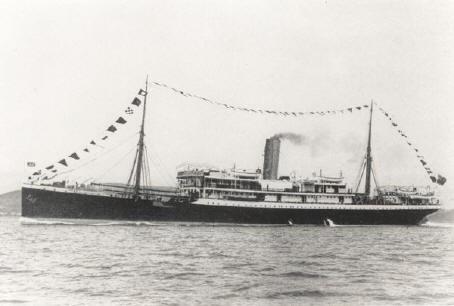

SS Darro (South African Museum of Military History)

The Mendi was a cargo ship of the Elder-Dempster line which was contracted to the British navy in 1916 and converted into a troop ship. Because the ship was a cargo ship in its previous period of commercial service, transporting goods between West Africa and the UK, the name Mendi derived from a Sierra Leone tribe, the Mendi, which comprises about 30% of the population of that country today and numbers about 1.5 million people (information from the Wessex Archaeology report - click here to view website).

The loss of the men of the Mendi together with the loss of the soldiers in the Battle of Delville Wood in July 1916 were regarded as two of South Africa’s worst war tragedies. There are several memorials to the men of the Mendi. Most significant is the one at Southampton England, the Hollybrook memorial; there is also a Mendi memorial at Atteridgeville in Pretoria, another in New Brighton, Port Elizabeth, one in Cape Town on the campus of the University of Cape Town (the site in Rosebank was where the Mendi men camped prior to their departure on the troopship). There is a memorial plaque and a lift buoy for the Mendi in Simonstown. In 1995 Queen Elizabeth unveiled a memorial at the Avalon Cemetery, Soweto. There is a Mendi memorial in Maseru to the Basotho men lost. There is also a memorial in Umtata with the names of the men of the Transkei who never returned. With the creation of the Military History Museum at Delville Wood in the 1980s the tragedy of the Mendi was portrayed on one of the pictorial bronze works of art. In July 2016, the names of those lost on the Mendi were added to the names of all South Africans who lost their lives in World War I recorded on the Portland stone panels lining the new walkway at Delville Wood, running from the old Baker Delville Wood Memorial to the Museum (which dates from 1985). This newest memorial was unveiled in July by President Zuma.

Commemoration of the 99th anniversary of the sinking of the Mendi at the Holybrook Memorial (Commonwealth War Graves Commission)

The news of the loss of the Mendi was not announced in the South African House of Assembly until the 9th March 1917 and when Prime Minister Louis Botha addressed the house all members rose as a mark of respect. Botha recalled that these were volunteers and he expressed the condolences and sympathies to the relatives of the men.

The story of the Mendi is part of a bigger story of the recruitment of South African black men to the South African Labour Contingent (often called the South African Labour Corp) for non-combatant labour service in France between the end of 1916 and 1918. In that period nearly 21 000 Black South African volunteers served with the SANLC in France. Other countries too provided labourers who served well behind the lines (though sometimes they were exposed).

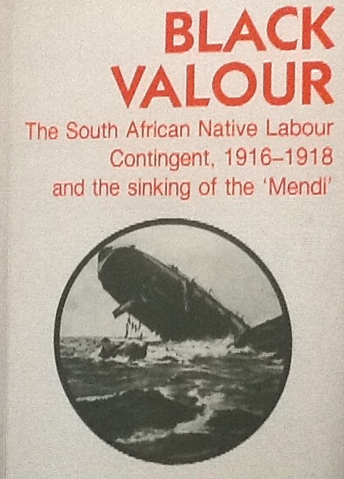

It used to be thought that the Mendi was a forgotten bit of South African history, and it has only been in recent years that the tragedy has been given rightful space and recognition in South African history. In my view, Norman Clothier’s 1987 book Black Valour: The South African Native Labour Contingent, 1916-1918, and the sinking of the Mendi remains the essential source of reference on the Mendi and the history of the South African Native labour Contingent. The Black experience in World War I was also covered by Albert Grundlingh in Fighting their Own War: South African Blacks and the First World War. The strength of this book lies in talking about conditions in South Africa’s rural areas and the reasons why men volunteered or were volunteered for service.

Black Valour book cover

Clothier makes the point that the SANLC received hardly any attention in standard older South African histories. Buchan in the official The South African Forces in France did not mention them at all. Clothier’s research was impressive because he collected information on the Mendi since the 1960s, but his serious writing began only in 1978 so he did not interview any survivors. However, his research covered a most comprehensive line up of official and unofficial manuscript sources, contemporary accounts, newspaper accounts, written memoirs and numerous letters. Clothier’s was therefore the first detailed account of the tragedy of the sinking of the Mendi.

Chapters devoted to the Mendi’s last Voyage, the actual sinking, the experiences of men who floundered or survived the icy waters, the aftermath of the sinking and finally the inquest and official Board of Trade enquiry are at the core of this study. It is a meticulous volume because wherever possible Clothier has attempted to use the first person accounts of what happened. Today it is possible to read the Board of Trade enquiry online and to find a more recent 2007 Wessex desk based archaeological investigation of the Mendi. But Clothier’s work in a pre-google era was a model of research.

Clothier also probed the extent to which the death dance and the address by the Rev Wauchope Dyobha actually took place. He weighed the evidence of written versus oral tradition, and came to the conclusion that there must have been a solid core to this great account of heroism in the face of death. It certainly was and still is an inspirational epic.

The remainder of his book tells of the work and experiences of the Labour Corp in France, their health and living conditions, the question of discipline, the cross cultural encounters and misunderstandings in language and cuisine. In 1918 the recruitment of men to serve in the Corp was disbanded and here there is some information about why the experiment in labour service was brought to an end. The last shipload of labour recruits arrived in France in January 1918. The labour volunteers had agreed to a year long contract and during 1918 the number of labourers in France declined (the last black troops left France at the end of September 1918). The question has been asked how politically active did black ex-servicemen become in the years thereafter. Clothier finds evidence of work in the Industrial and Commercial Workers Union in the 1920s.

Mendi Day on 21 February became for black South Africans what Delville Wood day meant for White South Africans. But there was huge resentment that black south African servicemen were not awarded medals for their service, in contrast to their white fellow soldiers. This was a disgrace and a blot on the record of successive governments.

Subsequent military and social history books have been very patchy in their coverage of the SANLC: Peter Digby’s Pyramids and Poppies (1993) concentrated on the First South African Infantry brigade in Libya, France and Flanders. Ian Uys wrote about Delville Wood in two superb books (1980s), but he included a section of the Mendi in his book Survivors of Africa’s Oceans (published 1993). Chris Schoeman: The Somme Chronicles South Africans on the Western Front (2014) only includes the role of Black South Africans in an Appendix. Bill Nasson’s Springboks on the Somme South Africa in the Great War 1914-1918 (2007) puts the SANLC into a broader context but he relies almost entirely on Clothier and Grundlingh. The Nasson book is excellent on the subject of memorialization.

The Schoeman and Nasson books

In recent years the Commonwealth War Graves Commission has declared the wreck site of the Mendi off the Isle of Wight an official war grave and there has been far more effort recently to make the story of the Mendi known to a much wider public. A short CWGC historical documentary and dramatization was shown in 2007. The Wessex Archaeological Report of 2007 was a significant British effort to put right historical neglect but its approach is strongly from the perspective of British nautical archaeology and its object is to address the issue of recreational dive sites and hallowed naval war graves. This year in July the Delville Wood Commemorative Trust published a Centenary Retrospective covering Delville Wood 1916-2016 and the Sinking of the SS Mendi 1917-2017, and gives the roll of honour of the men killed at the Battle of Delville Wood, the men lost on the Mendi and the names of all the members of the SA Labour contingent who lie buried at the Arques-la-Baataille cemetery, near Dieppe in France.

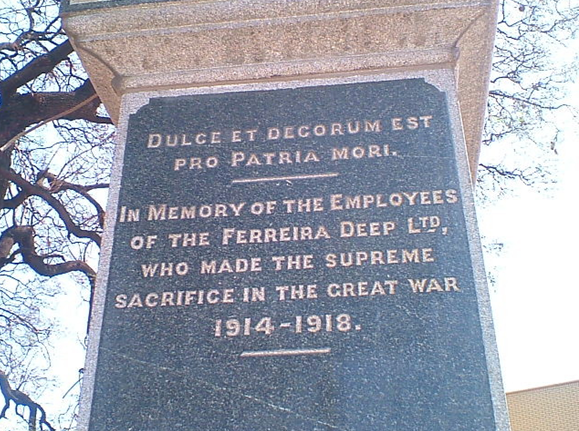

As a footnote, to add a Johannesburg link, the Selby War Memorial in Eloff Street Extension, is a war memorial to the men who were employed by the Ferreiras’ Deep mine in Johannesburg and who died for their country in World War I. I found one name connected to the Mendi: Sergeant Major T K Turner. I looked up Turner’s record in the CWGC archive. Turner had been a mine labour supervisor; recruited because he had had mine experience in managing black mine labourers. He was one of the men lost on the Mendi and was commemorated at the Hollybrook memorial, Southhampton. His cause of death: “lost at sea”, his widow was a MH Turner of 137 6th Avenue, Mayfair.

Ferreira Deep Memoria (City of Johannesburg)

Inscription on the Memorial (City of Johannesburg)

Click here to view details of an upcoming lecture by Kathy Munro on the SS Mendi (26 November 2016)

Kathy Munro is an Honorary Associate Professor in the School of Architecture and Planning at the University of the Witwatersrand. She enjoyed a long career as an academic and in management at Wits University. She trained as an economic historian. She is an enthusiastic book person and has built her own somewhat eclectic book collection over 40 years. Her interests cover Africana, Johannesburg history, history, art history, travel, business and banking histories.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.