Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

John Lincoln's series on the history of Cullinan continues with this look at the town between the wars (Click here to view the series index). It contains a spectrum of stories that occurred during a difficult period for Cullinan.

Below is an extract from the Résumé of operations from 1903 until 1932:

Mining and washing operations were entirely suspended from August 1914, until January 1916, when washing was resumed with the No. 3 Gear only, and confined to the treatment of tailings and cylinder lumps from the No. 1 Gear. Work in this connection was continued until July 1916, during which time 717,726 loads of tailings and lumps were treated which yielded 266,945 carats of diamonds equal to .372 ct. per load.

Hauling from the mine was resumed in July 1916, on the basis of two shifts of 8 hours each per diem, the output being restricted to the capacity of the No. 3 Gear, the No. 4 Plant having been closed down since August 1914.

For the period January 1916 to October 1920 – practically 5 years - the quantity of ground treated varied from 4,530,000 to 4,928,000 loads per annum, with a corresponding fluctuation in the annual output of diamonds between 814,500 and 906,300 carats, the highest figure attained being for the financial year ended 31st October 1920, when diamonds to the value of £2,098,483 were produced.

The total quantity of ground washed from January 1916 to 31st October 1920 was 20,496,760 loads, from which diamonds weighing 3,813,002 carats were recovered to a total value of £938,425. The highest price per carat realised for the product during this period was £2.11. 2 and the lowest £1.2.8. These figures afford a striking example of the benefits derived from the policy of control and limitation of production, disclosing, as they do, a substantial advance upon prices obtained during the period 1903 to 1914 when production was entirely unrestricted.

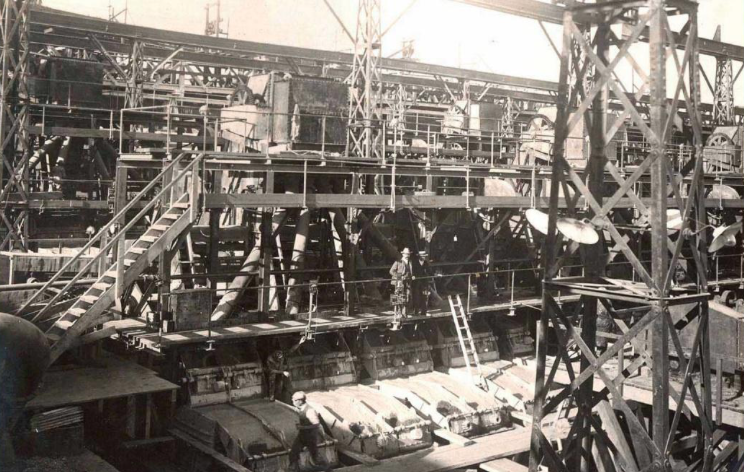

Endless rope haulage return wheel (Cullinan Mine Archive)

The daily average number of Europeans and natives in service was 451 and 4,600 respectively. In March 1918, a departure was made in regard to the working conditions hitherto in vogue, when, in response to pressure brought to bear upon the Company by the Labour Unions, who were very active at that time, it was agreed to introduce an 8 hour day in place of the shift of 10½ hours then being worked. Three shifts of 8 hours each per diem were accordingly inaugurated and work on this basis was continued until 31st October 1920, when, owing to the depression in the diamond trade, the Company was compelled to reduce the scale of its operations to two shifts of 8 hours each per diem.

It is worthy of note that the operation of the three shifts proved to be wholly unsatisfactory and costly, and was not justified by the results obtained in comparison with the former working conditions.

As already stated, owing to the depressed condition of the diamond trade, operations were restricted to two shifts of 8 hours on the 1st November 1920, when the services of 85 Europeans and 2,500 natives were dispensed with, and a further 225 men and 2,000 natives were discharged in March 1921, when mining and washing operations were reduced to one shift of 8 hours per diem.

On the 1st July 1921, operations were still further curtailed to a 5 day week on which basis work was continued until March 1922, when production on the normal scale, namely 2 shifts of 8 hours each per diem, was resumed.

Tom Cullinan and unknown person at No. 3 gear circa 1920 (Cullinan Mine Archive)

For the period November 1920 to October 1921, during which time operations were conducted on a restricted scale, the total quantity of ground lashed was 1,954,230 loads, from which diamonds weighing 411,981 carats were recovered equal to .211 ct. per load.

Expenditure during the same period amounted to £358,144 and the working profit to £110,385.

Operations were continued with the No. 3 gear until July 1926, when the No. 4 plant which had been idle since August 1914, was again brought into commission, and the No. 3 gear closed down.

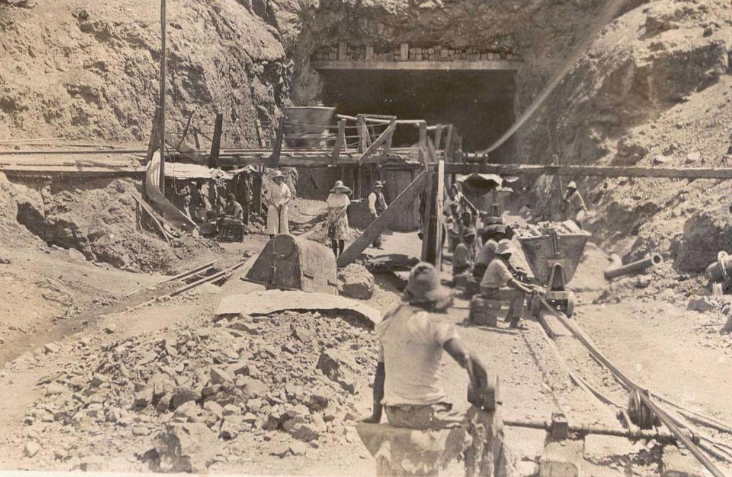

Entrance to the new Incline Shaft (Cullinan Mine Archive)

Below are recollections by Arrie Minnaar of life during the depression in the village translated from Afrikaans. Arrie was a descendent of the original owners of the farm Elandsfontein on which Premier Mine was found. They used to live in the now demolished part of the village called Hallsdorp.

The depression of 1933.

The good years are gone and times are now hard. The mine closed and the workers were forced to look for employment elsewhere. The mine authorities of Premier Mine did their best to assist the workers. It was decided to upgrade the road from Cullinan to the Molotto crossing and some of the dismissed workers were employed on this project.

The depression became a little brighter for residents still living in the area when it was decided to open the farm Bynespoort to diamond diggers. Each prospective digger had to apply for a claim of four square metres. To peg your claim involved a race to the diggings started by a pistol shot. The older people hired fit young boys to race for the claim for them. My eldest brother Roelf ran on behalf of my father and pegged a claim close to that of Koos Jonker.

Poverty slowly began to strike and fathers and sons all had to jump in to work their claims. I remember one day my father came home from the diggings and as usual my mother asked how the day had gone. With a slight smile on his face my father pulled out his wallet and from the wallet he extracted a yellowish stone. Mother looked at it and said: ‘Why is it such a strange colour?'

To test if it was in fact a diamond, a tennis ball was cut in half and the diamond left overnight in hydrochloric acid. If it was a diamond it would glitter and if it was crystal it would be dull and opaque.

My father took it to the diamond buyers. The diamond weighed 15 carats but was of a poor quality. They offered him £20 for it which my father was forced to take as times were tough. When my obviously disappointed father told my mother she said ‘Hush, my husband, perhaps next time you will get a better one.

One winter morning we woke with our father to go and work on our claim. The path to the claim was through a poplar wood. Dad was in front with his pick and sieve, my brother Flip was next and I brought up the rear carrying a shovel. We crossed over a ditch and I trod on a thorn which embedded in my foot. I sat down to pull the thorn out and my brother, who realised I was not behind him came back to see what the problem was. He knelt next to me but suddenly pointed to the side of the ditch and said ‘Hey, check there, is that a diamond?’ Just then my father arrived and told us to follow him and not to touch it. This is not part of the farm we now own, it now belongs to the Mine’ he said.

We arrived at our claim and dad went down into the claim on a ladder and filled a bucket with ground which we hauled to the top with a rope. We continued in this way but it was taking longer and longer to haul the bucket from the claim. But what could you expect, my brother was only seven and I not yet ten. When the sun was high in the sky, Dad told us to stop work to eat and rest. Whilst we were eating, Koos Jonker who had a claim next to us, came to see how the work was going and had coffee with us.

I was there on our claim one day when the same Koos Jonker jumped out of his claim screaming. He had in his hand a diamond, later to be weighed at 726 carats.

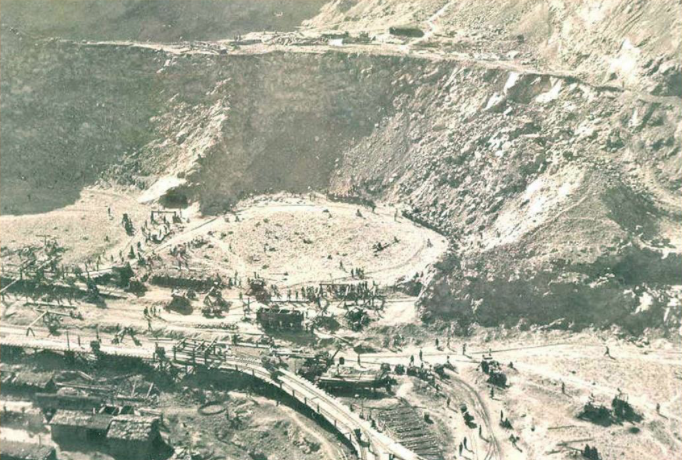

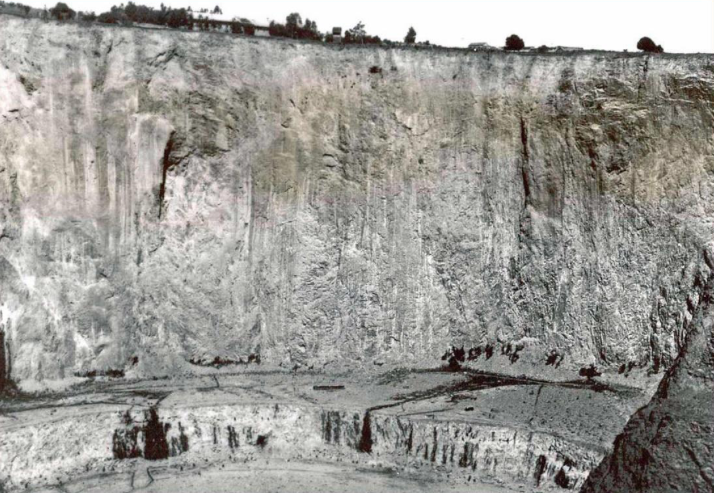

General view of the workings at 210ft. level (Cullinan Mine Archives)

Here is another extract from the Résumé of operations from 1903 until 1932:

For the period March 1922 to the 6th July 1931, washing operations were conducted on the basis of two shifts of 8 hours each per diem, with the exception of short intervals periodically when, in order to fulfil the quota allotted to the Company, two shifts of 10 hours were resorted to.

On the 6th July 1931, washing was restricted to one shift of 8 hours per diem when the Europeans employed at that date were placed on half time, and operations were pursued on this scale until the 31st March 1932, when the Mine was closed down owing to the prolonged depression in the diamond industry. Upon the cessation of mining operations, 331 Europeans were retrenched, and the natives - numbering 1232 - repatriated.

The services of 65 white men have been retained for the purpose of guarding the property and maintaining the essential services, while the retrenched employees have been permitted to remain in occupation of the Company's houses rent free, and are being provided with water, light, sanitary and medical services without charge.

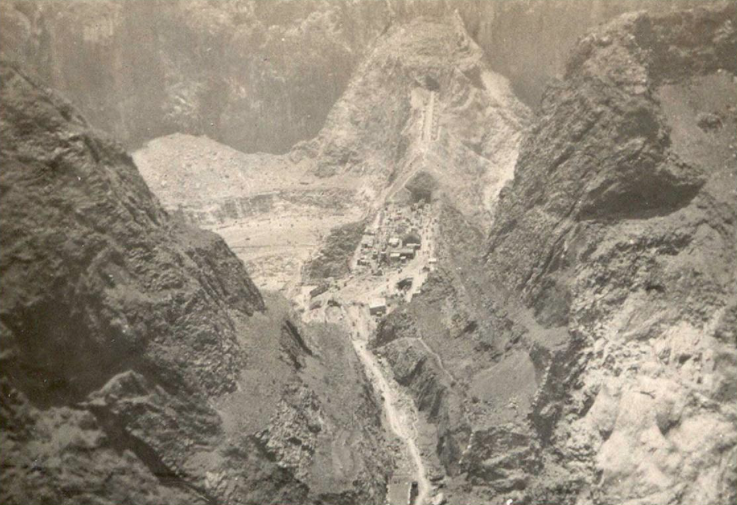

Haulage incline shaft (Cullinan Mine Archive)

Since the commencement of operations, the open-cast system of mining has been pursued, and the greatest depth attained in the Mine, at date, is 610 feet.

Owing to the encroachment of the bar of floating reef, the work-able area available on the 610 ft. level has been reduced to 2,000 claims, as compared with 2,800 claims in 1914 when operations were being conducted on a larger scale.

Under the system of working hitherto adopted, and having regard to the claim area available, it will not be possible, in future, to extract more than 18,000 loads per day of 24 hours from the mine, and for the treatment of this quantity ample capacity is afforded in the No. 4 Crushing and Washing Plant.

Workings on the south side circa 1925 (Cullinan Mine Archive)

Below is an extract from an article in The Star newspaper date 5 March 1921 with the headline: 'Appalling Distress on the Diggings. Dire effects of Diamond Slump. Men and their Families crying for food.'

The slump in diamonds that caused extensive retrenchment on the De Beers, Premier and Jagersfontein Mines has had an appalling effect on the alluvial diggers in the Western Transvaal.

On all the fields without exception starvation and worse is rampant. The Government officials in the nearby towns are powerless to appreciably diminish the awful distress prevailing, and the few small special grants that have been made by the Provincial authority have been swallowed up without even relieving the situation.

A representative of the “Star” had occasion to be in Wolmaransstad a few days ago, and in response to the representations of a number of responsible townspeople who urged the necessity of giving publicity to the position, a visit was made to several of the fields.

In the course of a journey of some 60 miles a close, personal investigation revealed a situation that completely beggared description. In all the camps there were pathetic cases of starving families: of parents powerless to relieve the painful cries of hungry children. Some had lost all hope of winning for themselves the precious contents some-times found in the dirty white gravel and are only too glad to hire themselves for a full day’s work turning the machine for a more fortunate washer for 2s or 3s. The latter will buy a bucket of meal at the stores.

There are hundreds of families who have not tasted meat in any form for months. One person haltingly and shamed-facedly begged a shilling from the writer to buy meat for his wife. She was sick and had not tasted any for five weeks.

Nearby in a shack I saw a woman, middle-aged and clean with a crying baby. The shack had a sack roof, and was marvellously clean considering the heavy afternoon downpour. She was reluctant to talk of her circumstances. Her husband had been admitted to hospital for a serious operation some weeks before leaving her with 4s and two children to keep. She had spent this amount on ginger and sugar, and made ginger beer, which she had carted around, to diggers in the hope of increasing her funds. The venture was a disaster, and she had sold a tickeys worth. Since then she had lived on what she could beg from her neighbours.

In one tent an aged couple was found with a little granddaughter who was dependent on them, her parents having succumbed to the influenza epidemic. It was raining heavily and as the rain poured through the worn shelter one wondered whether it was not less wet outside, but there was no word of complaint from the old pair.

One of the visitors produced an order for 30s worth of mealie meal and it was a touching sight to see the old couple laughing through their tears and it was learnt that they had been out of food since the morning.

Open pit in 1925, with the main onsetting station (Cullinan Mine Archives)

Main onsetting station (Cullinan Mine Archives)

West Mine Circa 1930 (Cullinan Mine Archives)

Open pit 1932 after it was closed (Cullinan Mine Archives)

Hole flooded before being pumped when the mine reopened in 1945 (Cullinan Mine Archives)

Oubaas the lion and the side-car

During the thirties there was an attorney on the mine called Mr Coetsee. His son Wiekie was a good friend of both my brother and I. During the winter Mr Coetsee used to go hunting near the Kruger Park. One day he came across a lioness which had been snared and was in a bad condition and he was forced to put the poor animal out of its misery. Unfortunately, the lioness had cubs. He brought one of the cubs back to Cullinan and reared it in a cage next to his house. The house was in Hallsdorp. He fed it donkey meat which in those days cost as little as one shilling per donkey.

One Sunday afternoon Wiekie, my brother and I decided to take the lion for a walk. We put a collar on the lion and attached a strong chain to it. Up the hill from Hallsdorp we went when suddenly the lion spotted a herd of donkeys grazing in a field. The chain went tight as we tried to stop the lion from getting at the donkeys. The chain slipped through our fingers as if there was grease on the chain and the lion attacked the donkey. I must tell you at this stage that the lion was called Oubaas. We shouted at the lion and he released his grip on the donkey, but he was growling fiercely at us. Wiekie then said, ‘Now we are in trouble, someone will have to go and get my father.’ Whilst he was saying this he looked at me and my brother.

We then ran back to Wiekie’s house and breathlessly knocked on the door. We heard the floorboards in the house creaking as Mr Coetsee walked to the door and then the shiny doorknob turned. He opened the door and fierce blue eyes looked down on us as he demanded ‘What do you want? Do you not know it is Sunday afternoon?’ ‘It’s Oubaas.’ my brother told him in a shaky voice.

'We think he has killed a donkey.’ ‘Where?’ Mr Coetsee thundered. Take me there.’ We told him where and hurried to keep up with him back to where Oubaas was.

When we arrived at the scene Mr Coetsee shouted, ‘Oubaas come here.’ We were surprised that the lion came to him and he took hold of the chain and said. ‘Okay, all of us back home now.’ Wiekie tried to explain what happened but was told to keep quiet. ‘We will talk at home’ he said.

When we got to his house we were all asked to tell Mr Coetsee what happened. Our excuses seemed to fall on deaf ears as we were all asked to bend and were rewarded with some blows to our backsides with his broad leather belt.

The mine mules used to graze on the hill close to the pen where Oubaas was kept. One Saturday afternoon one of these mules got too close and Oubaas charged at him. The wire pen collapsed under his weight and Oubaas got the mule by the throat. Mr Coetsee was once again called and it was with great difficulty that he managed to drag the lion off the mule. He now realised that it was no longer a cub but a young adult lion.

The mine gave him twenty-four hours to get the lion off the property. Arrangements were made with the curator of the zoo in Pretoria to take Oubaas. The agreement, however, was that the lion had to be personally delivered. This was easier said than done. Mr Coetsee’s friend had a motor-bike and side-car and the first attempt to get the lion to Pretoria was with this motor-bike.

The idea was to load the lion in the side car and Mr Coetsee to sit behind the driver and hold the lion in the side car with a short chain. With great difficulty they managed to get the lion in the sidecar but every time they moved off, the sound of the engine frightened the lion and he jumped out of the side car, dragging Mr Coetsee with him. Eventually they gave up.

The next option was Mr Coetsee’s Oldsmobile. The seats of the car were of fine canvas and they struggled to get the lion into the car. It can be said that the drive to Pretoria zoo was a difficult one and the seats were no longer fine canvas.

Oubaas adapted well at the zoo and grew up with a fine black mane and was a model of his species. Mr Coetsee was a regular visitor to the zoo to see Oubaas. On his visits to the zoo, other visitors could never understand why the lion would react to Mr Coetsee’s call and allow himself to be fondled.

Oubaas was a feature of the Pretoria zoo for many years.

The Pierneef Panel

Jacobus Hendrik Pierneff was born in Pretoria to Dutch/Afrikaner parentage in 1886. He studied art as a student in South Africa and in Holland, his parents having moved there due to the Second Boer War. It was during this time that he came in contact with the works of many of the old masters.

Pierneff returned to South Africa when he was eighteen. In 1913 he had his first solo exhibition which was well received. In 1929 he was commissioned to paint 32 panels for the Johannesburg Railway Station. These were installed in 1932 and were of various South African landscapes. He was reportedly paid R80 each for the panels.

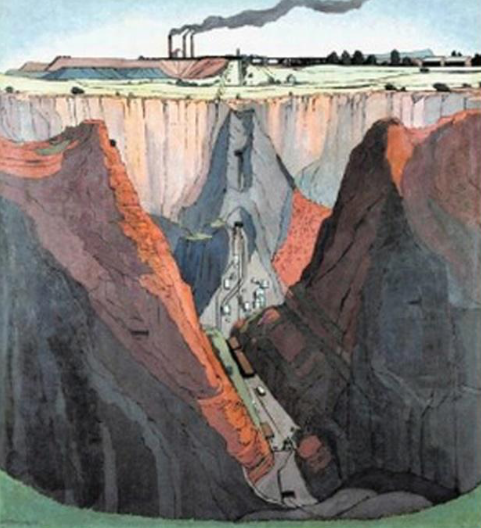

One of the panels was of the Premier Mine open pit. When he painted the panel of the open pit he also painted a water colour from the same position. The panel and the painting have very slight differences, the main difference being the direction of the wind, noticeable due to the smoke coming out of the chimney stacks of the power station.

The painting by Pierneef which was one of the 35 panels painted for the Johannesburg Railway station. A view from the east of the open pit showing the haulage and power station (Transnet Foundation)

The Pierneef watercolour of the mine (John Lincoln)

The amount for which he sold the painting is unknown, but it has been rumoured that he painted it for the mine in exchange for his accommodation. The panels were removed from the railway museum in 1971. Pierneff paintings often sell for, in excess of one million rand.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.