Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

Here is some exciting news for the heritage community. Dr Ronald Levine, antiquarian book collector and dealer, is offering a remarkable Railway manuscript and some attachments for sale as a single lot, on the Antiquarian Auction in June 2020 (see www.antiquarianauctions.com).

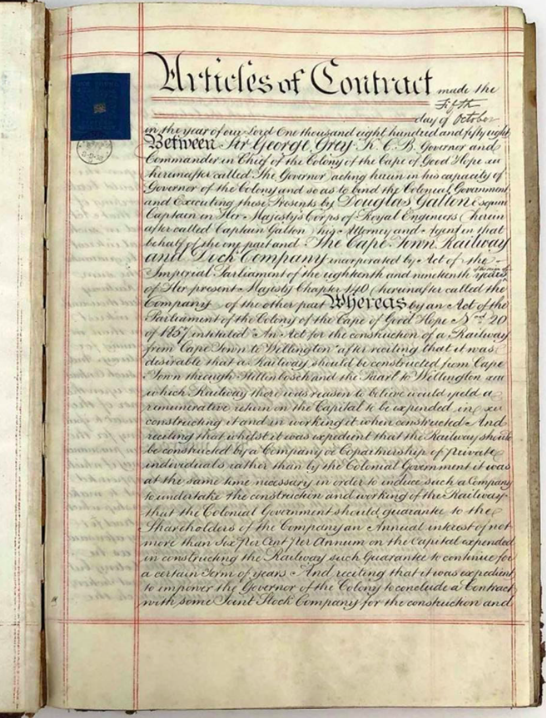

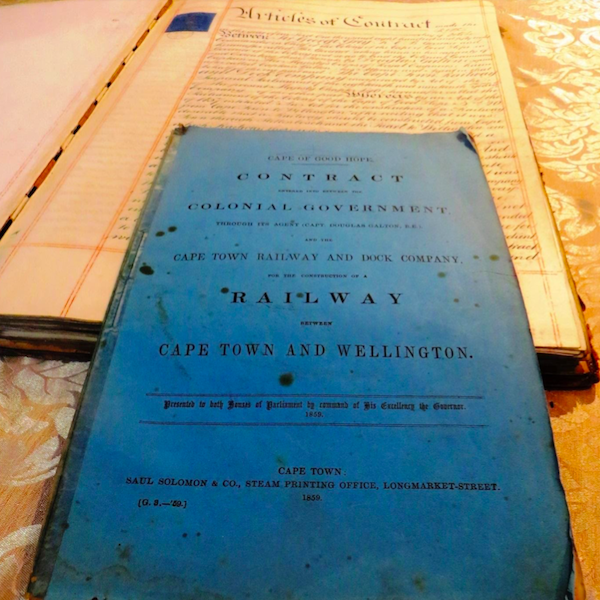

The central item, the manuscript, is an original Cape Railway contract in calligraphic script dated 1858. This document is unique and I concur with the view of Dr Levine that this is one of the earliest and most important items of South African railway history or Railwayana. It is a South African heritage treasure and an extraordinary legacy item from the Cape colonial era of the 19th century. For this reason Dr Levine has restricted sale to South Africa, which will ensure that the sale of the manuscript will comply with the National Heritage Resources Act and remain in South Africa.

The first page of the contract in calligraphy - hand written on parchment

When Dr Levine shared the news of this auction with me, my curiosity was roused and I decided to read up and give the document some historical context.

South Africa was relatively late to acquire its first railway lines. From the early 19th century, Railways and the steam engines revolutionised long distance travel between towns and across continents in Europe and in the USA. Africa, India, Australia, Russia and South America followed. For passengers, railways offered convenience and speed of movement and rapidly took over from coaches pulled by horses. The fact that the capacity of steam engines was expressed in horse power reveals the link to increasingly obsolete coaches.

Railways launched a second industrial revolution and the potential of steam rapidly spread around the world. The first railway with a steam powered engine was the Stockton and Darlington Railway constructed by Robert Stephenson and Company, to convey passengers over 25 miles between these two north eastern English towns in 1825. In the United States, the first steam locomotive (but running on wooden rails) ran in 1829. Dozens of companies were formed; everyone thought railway investments offered riches and the general public were caught up in bouts of share mania on stock exchanges in the major financial capitals.

For the most part railways were driven by private enterprise and the profit motive but government cooperation was necessary to deal with the legal frameworks, enable land purchases (sometimes through expropriation) and ultimately it was government that came to regulate and to own and run the railways.

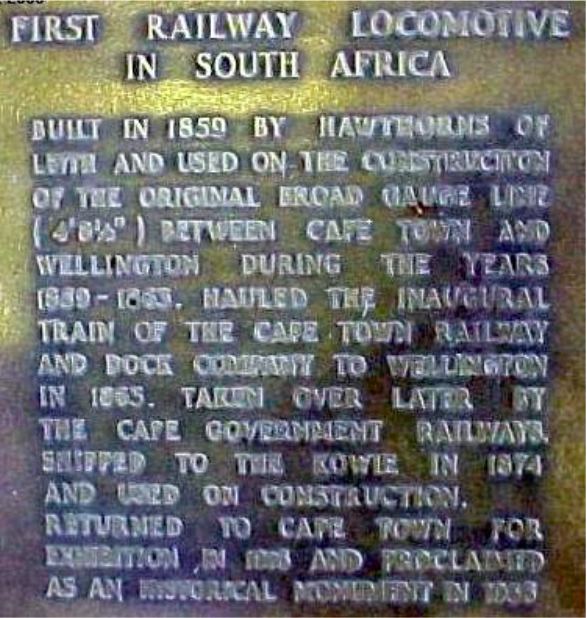

Blackie, the first steam locomotive of the Cape Town and Wellington Line - a national treasure (Danie van der Merwe)

Railways were also appealing to colonial interests of the British Empire. South Africa, Australia, India and New Zealand all wanted a slice of this engineering wonder. There were obstacles to overcome in a “distant” colony such as South Africa. Populations were sparsely settled and the port towns remote from one another. Distances were far greater than in Europe and the geographical terrain was challenging. Coastal towns needed connecting, but the interior could not generate a demand for a railway system. Local roads were even more essential than railways. Roads and railways were competitors in the early days. The lack of political unity in South Africa until 1910 made for competing political interests, for example between the Eastern and Western Cape. Industrial products had to be imported - there was no local iron industry and manufacturing concentrated on elementary consumer goods. Mountain passes were physical barriers. Who would invest in railways, who would build lines, and operate the railways? Could railways be profitable either for local or foreign investors? Should government or private companies own lines?

Jose Burman’s book “Early Railways at the Cape” (1964) gives the relevant background history. Whilst attempts were made to form a Cape of Good Hope Western Railway Company in London in 1845, it did not succeed because road construction was deemed to be the first priority. So another decade passed.

In 1853, the Cape Town Railway and Dock Company was formed, a London based company but with local connections. The Managing Director was G Lathom Browne, the consulting civil engineer was Sir Charles Fox. An investment sum of £500 000 was sought. Cape railways needed London Capital and local commitment. There also had to be Cape Colonial government involvement. By 1854 a local Select Committee investigated the project and presented its report. It concluded that a railway should be built by a private company, but with Government guaranteeing interest.

No progress followed, local interests talked but did not act. In 1857 there was another Government Select Committee. At that date it was the experienced railway engineer, John Scott Tucker who proposed the construction of a Cape Town to Wellington railway line. The Cape Parliament approved the plan and it was agreed that the line would run from Cape Town through Stellenbosch, on to Paarl and extend as far as Wellington.

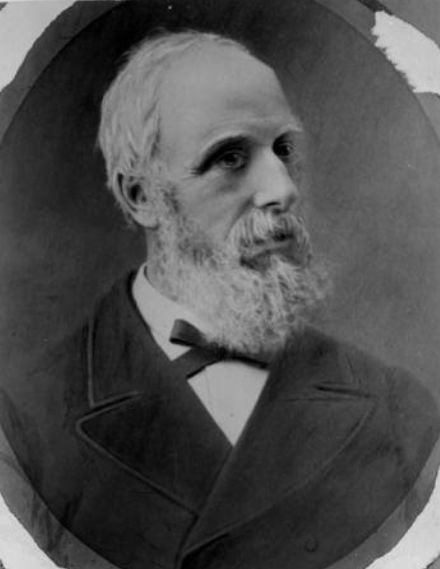

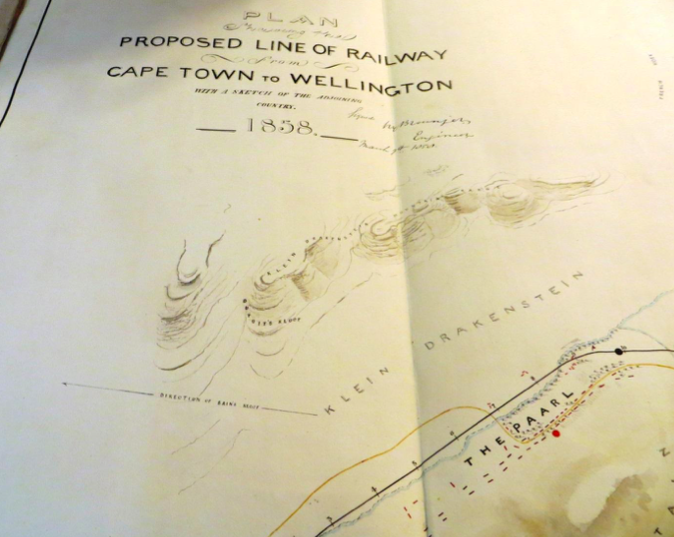

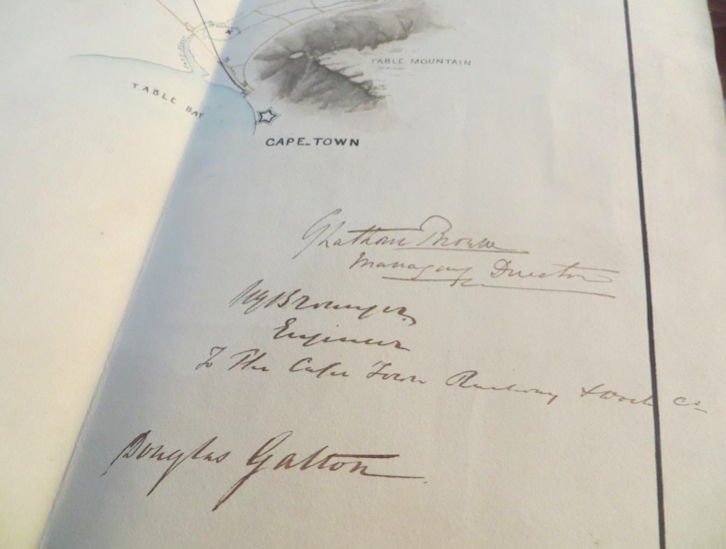

Enter a remarkable man, the civil engineer, William George Brounger, an Englishman born in 1820. He was a pupil of Charles Fox and as a young apprentice he was involved in the construction of the London Birmingham railway. He also worked on the 1851 Great Exhibition at Crystal Palace, London. Fox saw Brounger as the right man for the Cape project. Brounger was appointed the Resident Engineer in 1857. Within seven months Brounger completed a detailed survey of the proposed route. It is his map and plan that are included in the sale lot. Brounger earned a place in Rosenthal’s Southern African Dictionary of National Biography and G R Bozzoli’s book, Forging Ahead (1997 on pioneering engineers, also covered his Cape career).

Mr William George Brounger, pioneer of railways in South Africa (DRISA archive)

The winning tender was that of the Cape Town Railway and Dock Company and the contract was signed on 5th October 1858. The professionalism of the plans of the route suggest why the Cape Town Railway and Dock Company was the favoured competitor.

This contract, marked the start of South African inter-town railway. It is an example of an early, very hopeful, public private partnership with the potential for success despite the risks. The line was to be a single railway track, with an investment of £400 000; the Cape Government guaranteed an interest of 6 per cent per annum, making it attractive for London and Cape Town investors. After 20 years the Cape Government had the right to take over the line and this happened subsequently with the formation of the Cape Government Railways.

Meanwhile the first railway line actually constructed was in Durban, a short three mile line in Durban from the Point to the Market Square in the centre of the town, but note that the Cape contract pre-dated the Durban initiative.

The Cape project started but there were delays, slow progress, labour troubles and legal disputes. 159 labour recruits were shipwrecked en route to the Cape. There was no loss of life, the rescued men were routed to Pernambuco, Brazil before they eventually arrived at Cape Town.

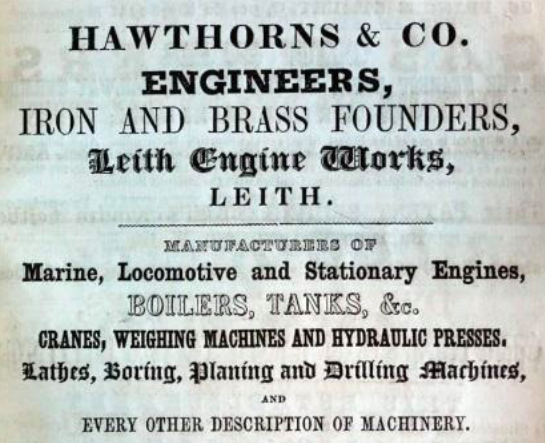

The first steam locomotive had to be imported and was manufactured in Leith, Scotland by Hawthorns and Company, a specialist Scottish engineering firm; they built railway engines specifically for Scottish railways and expanded into exports of engines. By 1872 they had produced a total of 400 steam engines.

An early advert for the firm of Hawthorns and Co. of Leith Scotland

The first locomotive in South Africa. Hawthorns & Co Leith Engine Works No.162 built in 1859 (via Old Steam Locomotives in South Africa)

The first engine arrived in 1859. In those days locomotives had names, but we only know this pioneering engine by the name it acquired later, Blackie. The driver, also an immigrant, was a William Dabbs. By 1860, the Cape Town company had purchased eight 4 ft 8 1⁄2 in (1,435 mm) broad gauge locomotives. They had names such as Fire Horse, Wellington and Sir George Grey. Built to last, these early locomotives remained in service on the Wellington line for over 20 years though were superseded when the Cape or narrow gauge lines were introduced in the 1870s.

The locomotives were painted in a green livery, very similar in shade to that of the Great Western Railway in England. This green colour became the standard passenger livery of the Cape Government Railways (formed in 1872). Colour coding became a form of identity and marketing.

The first railway locomotive was declared a national monument in 1933. This information is conveyed on a plaque mounted on a plinth at the base of the first railway locomotive in Cape Town Station. (via Wikipedia)

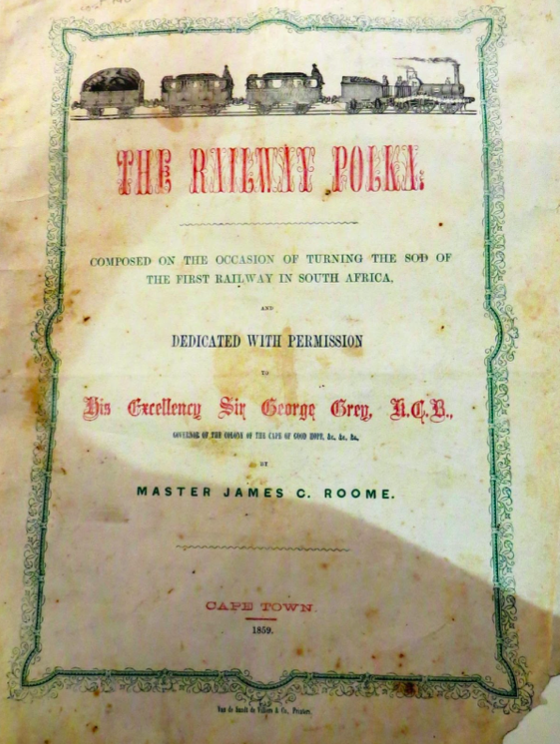

A celebratory ceremony took place in 1859 at Papendorp (now Woodstock) in the presence of the Cape Governor, Sir George Grey (also a signatory to the contract). Music was part of the festivities. A Railway Polka was composed and dedicated to Grey and a copy of this sheet music is part of the auction lot.

E Pickering was the construction contractor but he failed as it took him two years to lay the first 3 kms of track, the total length of the line was only 63 miles. Pickering was dismissed and a wild labour dispute erupted. The Cape Argus reported that Pickering’s men tore up iron rails and sleepers and ran one of the new locomotives, no 4, Wellington into a culvert and repairs were necessary.

It led to a Supreme Court action and eventually William Brounger, the resident engineer of the Cape Town Railways and Dock Company, stepped in and took over construction. Brounger was also responsible for operating the new railway.

One clear flaw in the project lay in the triangular relationship between the Cape Government, the entrepreneurial Cape Town Railway and Dock company and the contractor. It was a small local world of intense professional rivalries.

Members of the public took their train ride on 26 December 1860. What about speed? Steam power enabled the locomotives to achieve speeds of anywhere from 30 miles per hour (48 kms) up to 60 miles an hour. Workshops were established at Salt River.

By February 1862 the line had reached Eerste River, then Stellenbosch and finally arrived in Wellington. In 1863, a branch line was opened between Salt River and Wynberg. The project had reached conclusion.

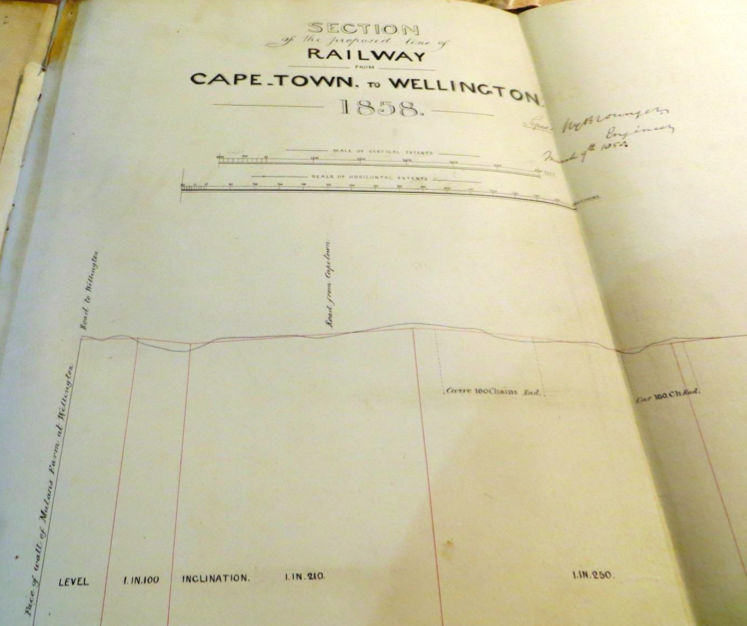

The contract also has an annexure of plans of the proposed route of the line, with the surveyors attempting to choose the least difficult terrain.

The challenge of the South African terrain

The plans pictured above illustrate that South African terrain presented a particular challenge. The continental terrain comprised a fairly narrow flat coastal plain, a steep escarpment and rugged inland mountain ranges which had to be conquered before the inland plateau was reached. Initially, the Cape chose the standard British broad gauge of 4ft 8 ½ inches (1,435 mm, designed for the English landscape). Africa was another proposition. As the railways pushed inland and the objective became to bring the railway to Kimberley, it was agreed in the 1870s that all new railways would be built to a narrow gauge of 3ft 6 inches (1,067 mm). This gauge became known as the Cape Gauge. The construction of lines through mountainous terrain and up the escarpment became more cost efficient. A drawback was that the narrow Cape gauge slowed speed until later technical advances in bogies.

Key signatures on the plan of the line included that of W G Brounger, 1858

Section plan of the proposed railway line from Cape Town to Wellington, 1858

Was the first railway project from Cape Town to Wellington a success? After 1863 the Cape economy went into decline. Confidence evaporated because the American Civil War caused a crisis in cotton supply to the UK.

Depression lasted from 1862-1870 and with the economy based on wool and nascent sugar, the economy was something of a backwater, and even more so when the Suze Canal (opening 1869 and under construction from 1859) undermined the route to the east around the Cape. This was a country of frontiers, mainly subsistence farming, limited trade, land hunger and conflict from competing agriculturalists, black and white. It took the diamond discovery and the mineral revolution for economic growth to take off and make railways an essential form of transport.

The Cape Government certainly wanted the line to continue further once it had reached Wellington. There is an interesting later history to the Cape Town Railway and Dock Company and in 1872 the Cape Government took over the Cape railways constructed up to that date.

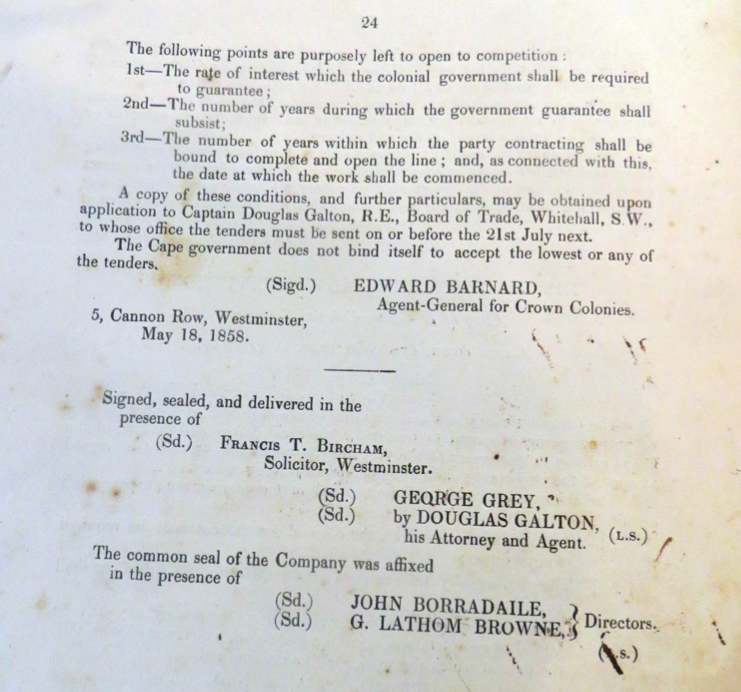

Final page of the Cape Government Blue Paper version of the contract showing the signatures - it would appear that this document was signed in London by Edward Barnard, the Agent-General for Crown Colonies.

A comment on provenance

When a rare collectable item of this significance comes onto the market the question of provenance arises. This particular manuscript can be traced back to the inventory and stock of Frank Thorold and Co, well known and most reputable Johannesburg antiquarian book dealers. Robin Fryde purchased Thorolds after the death of Frank Thorold in 1962 and the business remained in his possession until Robin’s death in 2011. We know that Robin Fryde was the owner of this contract.

The online viewing opens on Friday 12th June and the auction commences on Thursday 18th June and extends over a week. Click here for a longer version of this article.

The site for this sale is Antiquarian Auctions (click here to view).

Main image: The printed version of the contract in the form of the 1858 Blue Book which accompanies the leather bound hand written calligraphic version.

Acknowledgements: I thank Dr Ronald Levine for sharing his manuscript contract with me and allowing me to take photographs. All photographs taken by Dr R Levine or Prof K Munro

Kathy Munro is an Honorary Associate Professor in the School of Architecture and Planning at the University of the Witwatersrand and chair of the Johannesburg Heritage Foundation. She enjoyed a long career as an academic and in management at Wits University. She trained as an economic historian. She is an enthusiastic book person and has built her own somewhat eclectic book collection over 40 years. Her interests cover Africana, Johannesburg history, history, art history, travel, business and banking histories. She researches and writes on historical architecture and heritage matters. She is a member of the Board of the Johannesburg Heritage Foundation and is a docent at the Wits Arts Museum. She is currently working on a couple of projects on Johannesburg architects and is researching South African architects, war cemeteries and memorials. Kathy is a member of the online book community the Library thing and recommends this cataloging website and worldwide network as a book lover's haven.

References

- Jose Burman. Early Railways at the Cape

- C W de Kiewiet. A History of South Africa Social and Economic

- Bozzoli, G.R. Forging ahead: South Africa's pioneering engineers. Johannesburg: Witwatersrand University Press, 1997.

- Rosenthal, E. South African Dictionary of National Biography. London: Warne, 1966.

- Feinstein , Charles. An Economic History of South Africa, Conquest, discrimination and Development, Cambridge University Press, 2005

- Ball, Peter, Blood Sweat and Beers, the story of the railway navvy - posted online 6th January, 2017

- Grace’s Guide to British Industrial History. See entries on W G Brounger and Hawthorns and co of Leith.

- Murray Tony, Past Master: William George Brounger, Father of the South African Railways. Civil Engineering, July 2017

- Transnet Freight Heritage – 150 years of railway history.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.