Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

In the desolate reaches of the Canadian Arctic Circle, a mystery that has long baffled archaeologists and historians alike, is slowly unravelling. This is the fate of the lost Franklin Expedition. But to follow the full story, we must return to 1845.

The Expedition

On 19 May of that year, two ships of the British Admiralty, HMS Erebus at 370 Imperial tons and HMS Terror at 340 tons, were slowly departing Greenhithe on the Thames, downstream from London. Commanded by Sir John Franklin, a fifty-nine-year-old veteran of two previous arctic explorations, their objective was to find and navigate the elusive North West Passage. During the previous quarter century much progress had been made in exploring the Polar passages connecting the Atlantic to the Pacific Ocean and only about 100 kilometres of unknown channels needed to be explored to successfully complete the navigation of this Passage. Considered to be the best equipped Arctic expedition yet, it was inconceivable that it would fail in its given task.

Prior to departure Franklin received information from whalers that the previous winter in the Arctic had been exceptionally cold, but unable and unwilling to delay departure, he could only hope the following winters would be milder.

Quite recently scientists determined that the Franklin era was climatically one of the least favourable periods in the last 700 years to have explored the Arctic, which explains the thick pack ice encountered by Franklin off the north-west coast of King William Island. In Inuit folklore it is referred to as ‘the summers without sun’.

By June 1847, almost two years after the ships had disappeared into the Arctic, the first concerns were raised. Reluctant to appear alarmist, the Admiralty responded that since the expedition had sufficient food and provisions to last for at least three years, a relief expedition at that stage would be premature.

How then had this calamity come about?

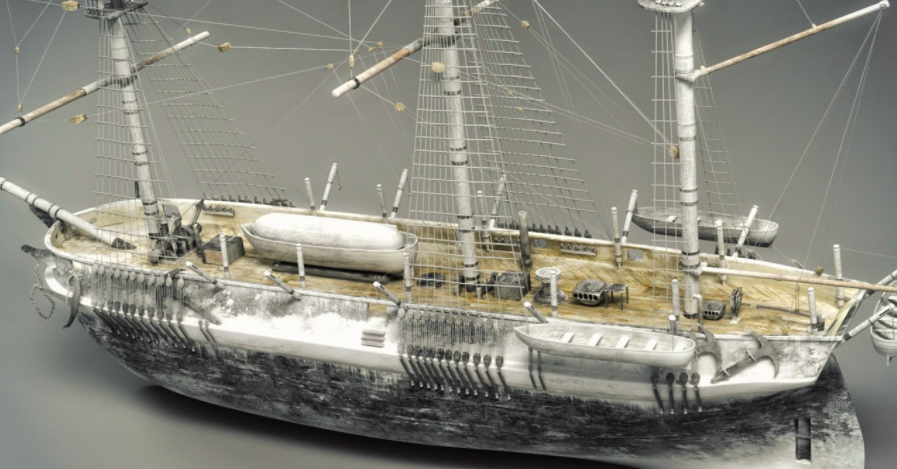

HMS Terror was commissioned in 1813 and HMS Erebus in 1826. Both were warships known as bomb vessels, mounting two large mortars weighing three tons each, to bombard coastal fortifications into submission. They were not big vessels, Erebus was only 32 meters long, and Terror half a meter less, but they were sturdily built and broad in the beam, like Sumo wrestlers. Their strong decks and hulls were specially designed to withstand the recoil of the two big mortars, while drawing a draft of only eleven feet, which would allow traversing the narrow and shallow Arctic passages.

These two ships proved their suitability for exploring the polar regions during a long exploration of the Antarctic during 1839-43, under command of Captain James Clark Ross. Here they sailed further south into what became known as the Ross Sea, than any other ship had ever been or would venture for the next sixty years.

For the exploration of the Antarctic, the Admiralty dockyards had doubled the thickness of the ships’ decks with a layer of waterproof cloth being sandwiched between the old and new layers. The interiors of the two ships were also braced fore and aft with oak beams to resist and absorb shock from ice and triple strength canvas was fitted for the sails.

The ships’ bows were further strengthened with sheet iron for the hazardous journey through the Northwest Passage. To cope with glacial Arctic winter conditions, Mr. Sylvester’s system, an early form of central heating was installed, which distributed warm air from a brick furnace to heat below decks.

Model of the Terror (Wiki Commons)

For emergency use, a steam locomotive with a specially adapted retractable propeller was installed in the after holds of each ship. Although these installations were cutting-edge technology for sailing ships at that time, they developed merely 25 and 20 horsepower respectively, insufficient to propel them through any thick ice. They would nevertheless come in handy to steer the ships through gaps in the ice during becalmed conditions.

As may be expected of a three-year expedition, considerable amounts of food and provisions were taken on board. The food comprised, amongst others, 61 987 kilograms of flour, 16 749 litres of liquor, 999 litres of wine, 4 287 kilograms chocolate, 1 069 kilograms tea and nearly 8 000 tins of varying sizes containing preserved meat, soups, and vegetables. Over 4 200 kilograms of lemon juice were loaded to avert scurvy. Large quantities tobacco, winter clothing, 1 225 kilograms of candles and plenty of other accoutrements were also loaded.

To keep the men entertained during the dark and cold winter months, each ship was provided with a hand organ that could play fifty tunes including ten hymns. Various instruments to research and record aspects of geology, botany and zoology also accompanied to expedition. For the first time a camera was taken along on an arctic expedition.

A transport vessel, the Barretto Junior, accompanied the two ships to the Whalefish Islands off the West coast of Greenland, carting ten live oxen and additional supplies. Here the oxen were slaughtered for fresh meat and together with the other supplies transferred to the Erebus and Terror.

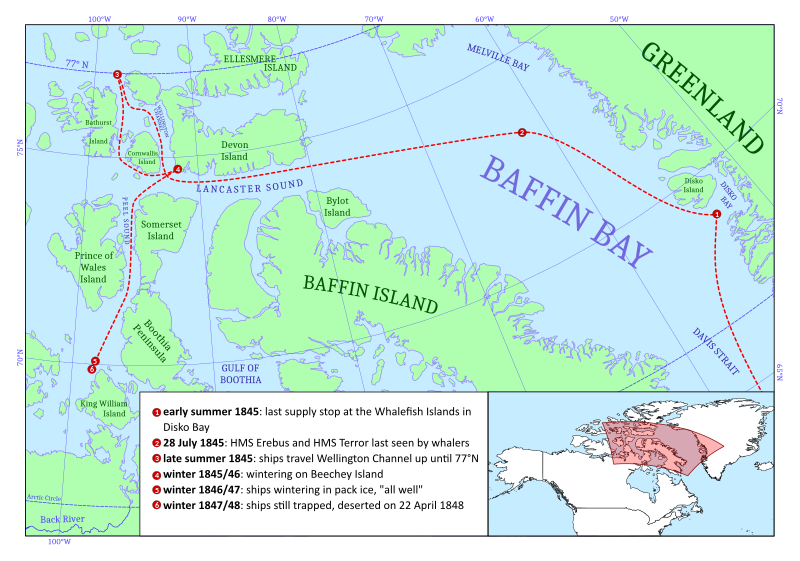

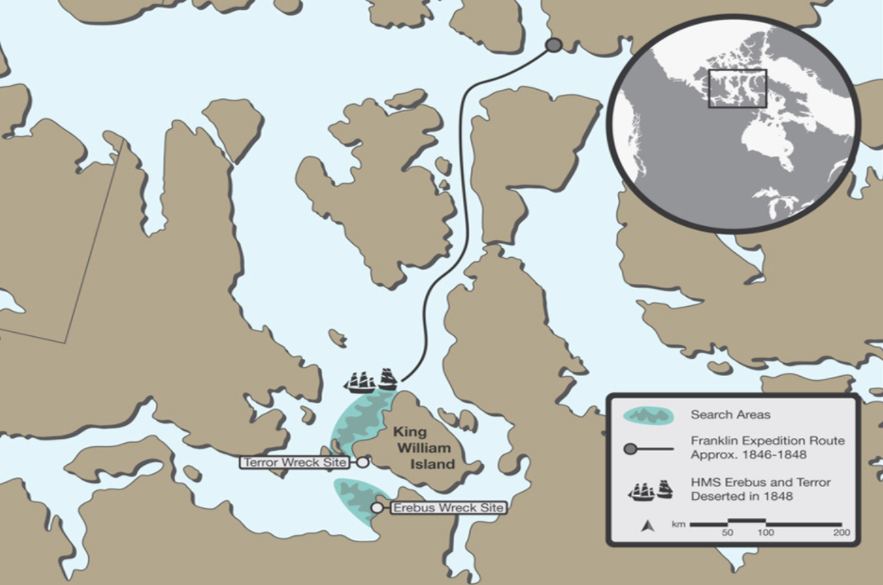

Approximate route of the Franklin Expedition (Wiki Commons)

On 12 July 1845, the expedition departed the Whalefish Islands steering west-north west. At the end of July, they met up with two whaling vessels in Baffin Bay, where Franklin was awaiting suitable conditions to cross to Lancaster Sound. On 28 July 1845, as contrary winds separated them from the whalers, the Erebus and Terror were seen for the last time. Little did the Franklin men realise they were about to enter a world of snow and ice from which they would never emerge.

Robert Martin, Captain of one of the whaling ships, later recalled Franklin saying they had sufficient provisions for five years that could be extended to seven years, if necessary.

Searching for the Lost Expedition

Finally relenting to public pressure in the winter of 1847-8, the Admiralty dispatched three relief expeditions. One sailed for the Bering Strait to search the coast of Alaska, where nothing was found. An overland party worked their way down the lower reaches of the Mackenzie River to the coast and explored the channels between the Banks and Victoria Islands. While much useful surveying was completed, no trace was found of the Franklin Expedition. The third relief expedition sailing on the Enterprise under the experienced James Clark Ross crossed Baffin Bay into Lancaster Sound in the summer of 1848, where heavy ice blocked all the passages. The Clark Ross expedition was experiencing firsthand the extreme glacial conditions that had confronted Franklin since 1845. Wintering on the north eastern tip of Somerset Island, the intense cold prevented any searches until May 1849, when Ross’s party was able to explore the north and west coasts of Somerset Island, hauling their sledges by hand. Finding the Peel Sound so blocked with impenetrable pack ice that any passage appeared impossible, they left provisions at various points before withdrawing to their ship. During this epic journey across Somerset Island they travelled 800 kilometres in merely thirty-nine days while hauling sledges across extreme arctic conditions.

Modern cruise through the Peel Sound (Wiki Commons)

When the Ross Expedition also returned empty handed, fears of an impending tragedy began to replace the high hopes of a successful rescue. Over the next ten years more than thirty expeditions set off to the Arctic to search for the Franklin Expedition.

Finally, in August 1850, more than five years after the departure of the Franklin Expedition, Captain Erasmus Ommanney of HMS Assistance, found some remnants at Cape Riley on the south-western tip of Devon Island. From the traces found, it appeared Franklin had wintered here during 1845/46. This was almost immediately followed by the discovery of three graves on the nearby tiny Beechey Island.

The wooden headboards declared them to be the graves of Leading Stoker John Torrington, Able Seaman John Hartnell and Royal Marine William Braine. The first two died during January 1846 and Braine on 3 April 1846.

On the right, three graves from the Franklin Expedition on Beechey Island. The grave on the left is that of Thomas Morgan, who died in 1854, a member of the McClure Expedition (Wiki Commons)

Following the above discoveries, the trail of the Franklin Expedition went cold again. Unfortunately for the rescue expeditions, Franklin, either through overconfidence or neglect, omitted to leave directions of his route in strategically placed stone cairns.

Therefore, not quite knowing where to proceed from there, the best option seemed to follow the route the Admiralty had instructed Franklin to follow, west through Lancaster Sound and Barrow Strait to Cape Walker and from there to the Bering Strait. Captain Ommanney therefore sailed to Cape Walker on Russell Island to the north of Prince of Wales Island. He found nothing and concluded Franklin would not have been able to sail directly from Cape Walker to the Bering Strait, as this route was totally and impassably blocked by thick ice.

An overland party led by Dr. John Rae from Stromness in the Orkney Islands, who was employed by the Hudson Bay Company, explored the west coast of Victoria Strait. There he found two pieces that appeared to be from ships’ wreckage. One was an oak stanchion and the other looked to be part of the flagstaff of a cutter. Both pieces bore the imprint of a broad arrow, with which all Royal Navy equipment was marked. Since nobody knew which route Franklin had taken, Rae assumed the fragments must have drifted down from the north.

At this stage it appeared that Franklin had not gone west of Cape Walker nor any of the heavily iced channels to the south. This left the Wellington Channel to the north between Cornwallis Island and Devon Island, which was one of the alternative routes recommended by the Admiralty if the others were blocked by ice. An Admiralty expedition therefore sailed up the Wellington Channel and investigated Melville Island, but again no traces of the Franklin Expedition were found.

With no further information forthcoming, a notice appeared in the London Gazette on 10 January 1854 that unless news to the contrary were received by the end of March, the men of the HMS Erebus and HMS Terror would be considered to have died in Her Majesty’s Service.

Finding Relics and Remains

But only a few months after the above announcement, unexpected news emerged. John Rae had travelled Inuit style to the Boothia Gulf, to complete the first survey of this remote area. Here he met up with an Inuit named Inukpuhiijuk who was keen on trading with him. When Rae, through an interpreter asked him whether he had seen any foreigners in the area, he replied in the negative, but explained he had overheard others referring to a large group of white men who had perished somewhere to the west. Rae purchased various items from the Inuit, including a silver spoon and fork engraved with the family crest and the initials F.R.M.C., those of Francis Crozier, Captain of the Terror. He also bought Franklin’s Guelphic Order of the Hanover Medal awarded for his service in the Mediterranean. Slowly, Rae with assistance from Inukpuhiijuk and other Inuit, pieced together the last days of the survivors of the Franklin Expedition. They explained a group of about forty men were seen travelling southwards from King William Island four winters past (1850). Dragging sledges, one of which had a boat on it, they communicated by sign language their ship had been crushed by the ice. Most of the men were thin and weak but their leader was described as tall, broad, and middle-aged. This description could well have matched that of Crozier. He bought some seal meat from the Inuit and with both parties unable to communicate further, went on their respective ways.

Tombstone of Arctic explorer John Rae, in St Magnus Cathedral in Kirkness, Orkney Islands, who discovered the first remnants and oral information of the fate of the Franklin Expedition (Wiki Commons)

Francis Crozier, Captain of the Terror (Wiki Commons)

The Inuit added that later that same winter the remains of thirty men were discovered on the mainland with five bodies on a nearby island. Some of the bodies were found in tents and other under an upturned boat. Seemingly, they were close to the mouth of the Back’s Fish River. The Inuit then dropped a bombshell. From the state of the mutilated bodies and the contents of the cooking pots, it appeared the survivors had in desperation resorted to cannibalism.

Rae’s report to the Admiralty, including the Inuit allegations of cannibalism was published in The Times and caused an immediate uproar. Critics refused to accept any suggestion that British sailors would have resorted to cannibalism, and roundly criticised Rae for not following up on the Inuit reports, instead of hurrying back to London.

Lady Franklin, with assistance of a public appeal for funds and a donation of supplies by the Admiralty, purchased a small steam yacht, the Fox, to continue the search for the Franklin Expedition. This small vessel with a crew of only twenty-five, most of whom had previous Arctic experience was commanded by Captain Francis M’Clintock, a Royal Navy officer who had participated in three earlier Franklin search expeditions. The Fox departed England in July 1857 but became locked in the winter ice in Baffin Bay, only able to proceed further at the end of April 1858. The expedition then steamed down the Peel Sound but finding ice blocking their route, turned back to sail around the top of Somerset Island and then south down the Gulf of Boothia before steering west through a recently discovered narrow channel, the Bellot Strait that connected the Gulf of Boothia to the Peel Sound.

Unfortunately, the western exit of the Bellot Strait into the Peel Sound was blocked by ice and it was only in February 1859, that the expedition was able to commence travelling with sledges hauled by men and dogs. Traveling down the west coast of the Boothia Peninsula, McClintock and his companions encountered Inuit willing to sell relics. Some spoke of a ship that had been seen to sink off the west coast of King William Island while others told of a ship forced ashore there by ice.

When they reached Cape Victoria on the south-western coast of the Boothia Peninsula, the M’Clintock Expedition split up. M’Clintock resolved to travel down the east coast of King William Island to the mainland and the estuary of the Back’s Fish River and before returning along the west coast of King William Island. Lieutenant William Hobson, his second in command was instructed to search the west coast of King William Island for possible clues.

Hobson’s party was first to locate solid evidence that the Franklin men had passed this way. On 3 May 1859, a stone cairn, and the remains of a bivouac near Cape Felix on the northern tip of King William Island were discovered. A thorough search of the cairn disappointingly only yielded a blank piece of paper, on which the pencil inscription may have faded. The abandoned bivouac contained three small collapsed tents covering some bear skins and blankets that appeared to have been occupied by about twelve men. Hobson opined that the bivouac seemed to be hastily abandoned and that the men must have returned to their ship.

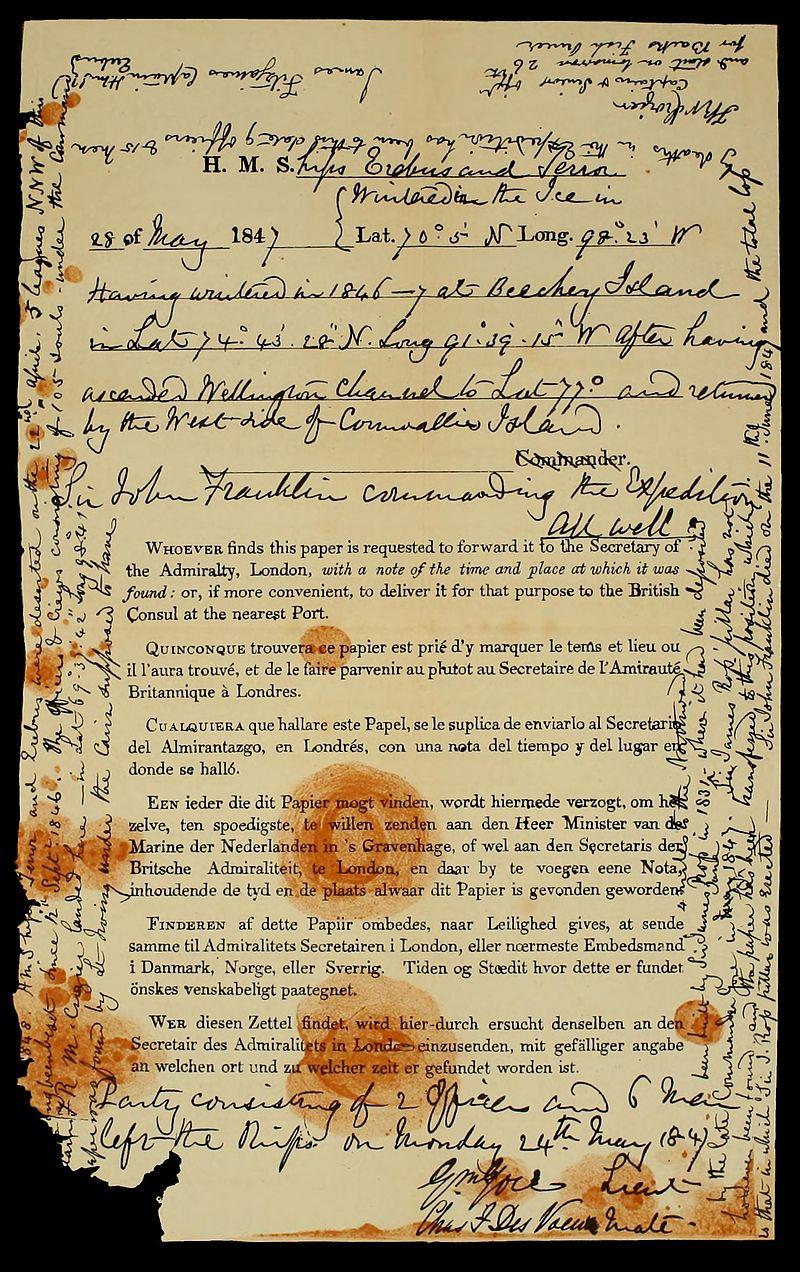

Three days later a second cairn was found, again without any message. A short distance further south they discovered a third stone cairn with a large amount of gear scattered about. Searching with mounting excitement amongst the stones, a small cylinder containing an Admiralty regulation form was soon spotted.

The first note scribbled on the form, dated 28 May 1847, contained the reassuring message:

HMS Ships Erebus and Terror, wintered in the ice in Lat. 70º 5’ N Long. 98º 23’ W. Having wintered in 1846-7 at Beechey Island, in Lat. 74º 43’ 28” N, Long. 90º 39’ 15” W, after having ascended Wellington Channel to Lat. 77º, and returned by the west side of Cornwallis Island. Sir John Franklin commanding the expedition. All well. Party consisting of 2 officers and 6 men left the ships on Monday 24th May 1847. Gm. Gore, Lieut. Chas F. Des Voeux, mate.

But around the margin of this form appeared a second hastily scribbled note far more ominous than the first. Dictated by Captain Crozier to Commander Fitzjames, almost a year after the first, it told of the disaster that befell the Franklin Expedition.

April 25th, 1848 – HM’s Ships Terror and Erebus were deserted on 22nd April, 5 leagues N. N. W. of this, having been beset since 12th September 1846. The officers and crews, consisting of 105 souls, under command of Captain F. R. M. Crozier, landed here in Lat 69º 37’ 42” N, Long. 98º 41’ W. This paper was found by Lt. Irving under the cairn supposed to have been built by Sir James Ross in 1831, 4 miles to the northward, where it had been deposited by the late Commander Gore in June 1847. Sir James Ross’ pillar has however not been found, and the paper has been transferred to this position, which is that in which Sir James Ross’ pillar was erected. Sir John Franklin died on 11th June 1847; and the total loss by deaths in the Expedition had been to this date 9 officers and 15 men.

James Fitzjames Captain HMS Erebus.

F. R. M. Crozier, Captain and Senior officer.

And start tomorrow, 26th, for Black’s Fish River.

The scribbled notes on an Admiralty Regulation Form, of the Erebus and Terror being abandoned on 22 April 1848 (Wiki Commons)

‘So sad a tale was never told in fewer words’, M’Clintock lamented after learning of the discovery some weeks later.

One mistake in the first message was quickly noted, the expedition had wintered at Beechey Island in 1845-6, not 1846-7 as stated on the note.

Daguerre-type image of Sir John Franklin taken prior to departure (Wiki Commons)

Around the cairn a vast quantity of clothing and stores of all sorts lay scattered around, as if at this spot every article that could be dispensed with was thrown away, such as pickaxes, shovels, boats, cooking stoves canvas, instruments, oars and medicine chests.

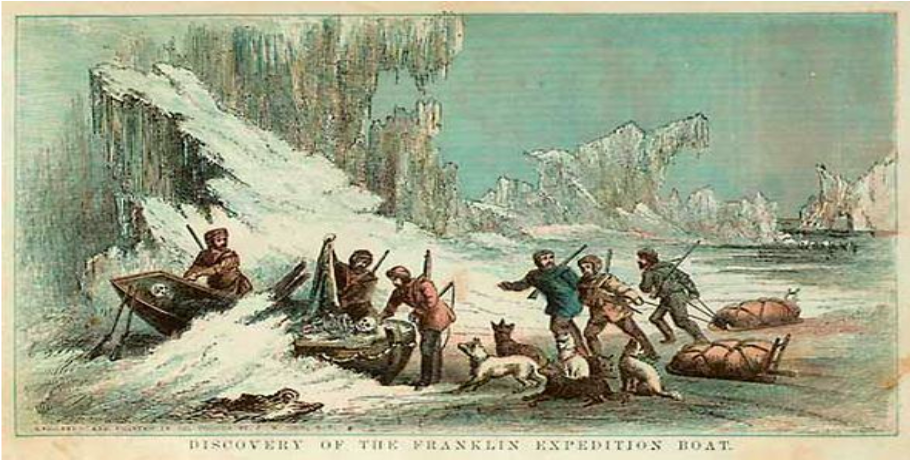

On 24 May 1859 about 50 kilometres further south, Hobson discovered a large ship’s boat on the beach containing two skeletons and filled with much equipment. M’Clintock later named this area on the western extreme of King William Island, Cape Crozier. The boat was 8.5 meters long and M’Clintock estimated the combined weight of the boat and oak sledge it was mounted on at 635 kilograms. The boat contained large quantities of goods, most of which M’Clintock considered ‘mere accumulation of dead weight, of little use and very likely to break down the strength of the sledge crew’. The boat’s bow pointed towards where the Erebus and Terror had been abandoned, as if the survivors had changed their minds and were retreating to their ships.

Discovery of the Franklin Expedition Boat

Crippled by scurvy, Hobson, and his men returned to the Fox, seventy-four days after they set out with the sensational news of their discoveries.

McClintock's party arrived four days later. They had not found much on their outward journey or at the Back’s Fish River estuary, but on the return journey on the south coast of King William Island they came across a bleached skeleton lying face down on a gravel ridge. From pieces of the uniform it was identified as a steward, probably Thomas Armitage, gun-room steward on the Terror. Nearby lay a small pocketbook, containing indecipherable writings and drawings, which might have belonged to Henry Peglar, a close friend of Armitage. Written during the expedition, none of the messages seemed important and some were indecipherable but given the lack of written material from the expedition this booklet may yet turn out to be an important source of information.

With this tragic but dramatic news the Fox returned to England in September 1859. The success of the expedition deservedly brought honour and fame to M’Clintock and Hobson and perhaps some comfort to Lady Franklin.

How did it go so wrong?

With the benefit of hindsight, we can surmise how and where things had gone wrong. When the Erebus and the Terror departed Beechey Island during the summer of 1846, they sailed south-west down the Peel Sound until beset in thick pack ice on 12 September 1846, just off the north-western coast of King William Island. Franklin clearly believed this route would eventually lead him to the mainline coast he had explored two decades prior. He and his officers were probably initially not too concerned about being trapped in the pack ice, fully anticipating the ships to break free during the following summer of 1847, when the ice was expected to thaw.

Where the Erebus and Terror were abandoned (via Wiki Commons)

Franklin’s incomplete maps would have informed him and his senior officers that they only needed to sail the 100 kilometre stretch from King William Island to the mainland to find the elusive Northwest Passage. Unfortunately for the expedition, the early explorers of that area were under the impression that the stretch of land now called King William Island, but then known as King William Land, was an isthmus of the Boothia Peninsula. Franklin, no doubt familiar with the maps and descriptions of the earlier explorers probably believed he had to sail to the west of King William Land, since the route to the east would lead to a dead end. By turning the ships towards the south-west of this island, he sailed directly into the continuously replenished pack ice that grinds down from the north-west into the length of what was later called the M’Clintock Channel. This ice mass does not always clear during the short summers, whereas the channel to the east of King William Island often does. Amundsen demonstrated this when he sailed east of King William Island to complete the first successful navigation of the North West Passage in 1903-6.

It must have been very disheartening for the expedition when the Victoria Strait, as this channel is known, failed against all expectations to clear during the summer of 1847. By now provisions were starting to run low and all fresh produce had long since been consumed. The depressing thought of spending a third freezing winter trapped in ice, the ships continuously jostled and scraped by the pack ice, surviving on a monotonous and unhealthy diet of tinned food and with no certainty whether their vessels would be freed even during the next summer of 1848, must have weighed heavily on the men’s minds.

Michael Palin in his book Erebus the story of a ship, quotes the dismal comment of Henry Piers, the assistant surgeon on the Investigator, trapped during the winter in ice off Banks Island in 1852:

... let anyone imagine a ship frozen up, with the deck covered with snow a foot or eighteen inches deep … a temperature of minus 30 or 40 with strong wind …the fine snow drift …finding its way through and covering everything, the wind howling through the rigging at the same time: let him picture to himself then this covered deck lit by a single candle in a lantern; five or six officers walking the starboard side and maintaining some conversation, and twenty or thirty men, perfectly mute, slowly pacing the port side, muffled up to their eyes and covered with snow drift or frozen vapour … he will then have some idea of many of this winter’s day’s exercise.

Why did so many aboard the ships die?

During the eleven-month period between Lieutenant Graham Gore’s reassuring message of 28 May 1847 until 22 April 1848, when the ships were finally abandoned, the Expedition suffered the very high death rate of nine officers and fifteen men, almost twenty percent of its total strength. The last winter of 1847-8 must have been the killer. One can only imagine how depressing it must have been for the men’s morale to have to bury two of their shipmates per month. But why such a high figure?

The state of health of the men has been hotly debated ever since the discovery of the human remains on Beechey and King William Islands. Various theories have been advanced including food poisoning, because of poor quality tinned food provided by Hungarian manufacturer Stephen Goldner. Although Goldner’s tinned food was on one occasion rejected by an Admiralty shipyard because of quality concerns, he also won a prize at the Great Exhibition in 1851. One would expect an outbreak of acute food poisoning or botulism to have killed off the crew much sooner.

According to the US Department of Agriculture, low acidic canned food such as soups, stews, meats, and vegetables, can last almost indefinitely but will taste best between two and five years from date of manufacture. High acidic canned food such as lemon juice, berries, sauerkraut, and all foods treated with vinegar-based sauces or dressings are good for about twelve to eighteen months of storage.

Richard Cyriax, a respected scholar of the Franklin Expedition, maintained in his 1939 book, ‘Sir John Franklin’s Last Arctic Expedition’ that scurvy was the main cause of death. He quoted statements from Inuit that they had seen White men with bad teeth and swollen gums, an indication of scurvy. An Inuit woman also told American explorer Frederick Schwatka who searched for the Franklin Expedition in 1878-9, that the men she had met were thin and their mouths were ‘dry and black’. This would corroborate the known deterioration of anti-scorbutic rations, such as lemon juice over time. Cyriax pointed out that the gestation period for scurvy takes some time. The symptoms of the disease may not appear for twelve months or even longer, but when it does, it takes effect rapidly.

According to Michael Palin, this could account for the rapid increase in deaths in the third winter (1847-8) and may well be the reason why Crozier and Fitzjames felt they had to abandon the ships and travel overland to seek help.

In 1984, anthropologist Dr Owen Beattie obtained permission to exhume the remains of the three members of the Franklin Expedition buried on Beechey island.

Casket and remains of Able Seaman John Hartnell disinterred from the permafrost on Beechey Island. Hartnell’s forehead and nose were discoloured by a covering blue cloth (Wiki Commons)

Beaty had previously conducted important fieldwork on King William Island when he discovered some remains of the Franklin Men. Shallow pitting and scaling on the outer surface on the human bones were observed like those seen in described cases of Vitamin C deficiency, the cause of scurvy. He also found a femur bone of a long dead member of the expedition that contained cut-marks, most likely made by a sharp instrument, which seems to corroborate the Inuit reports of cannibalism being practiced amongst the dying men. Laboratory analysis of the bone fragments also indicated very high levels of lead. Beattie was however concerned that long exposure to the harsh climate might have affected the bone fragments and hence also the analysis. He therefore wished to compare the analysis of the bone fragments with samples taken from the remains of the three men buried at Beechey Island.

Analysis of hair samples removed from the bodies at Beechey Island also showed markedly high levels of lead. In their book Frozen in Time, Beattie and John Geiger argued that the excessive lead soldering applied to seal the tinned cans had leached into the food, causing lead poisoning.

Other historians disputed this, reasoning that the prevalence of lead piping in Victorian England, would in any case have caused elevated levels of lead. It was further argued the period onboard the ships would have been too brief to cause acute lead poisoning of the men.

Therefore, the most likely scenario seems that those who died while still on the ships must have succumbed to various illnesses and diseases because of poor health brought on by lack of a balanced diet and the extreme cold. Once the surviving but weakened men abandoned the ships it was only a matter of time before they too died from exposure and exhaustion aggravated by hunger and starvation.

When the men abandoned their ships on 22 April 1848, three years after departing Greenhithe, their slender hope was to haul some of the ships’ boats to the estuary of the Back’s Fish River. There is some evidence that they might have tried to haul three boats along this route. Hobson and M’Clintock found one and the Inuit claimed to have found the other two. But even if these weakened men reached the estuary of this river the odds remained heavily stacked against them. They would have had to sail, row and portage nearly 1500 kilometres upstream of one of the most dangerous rivers on the mainland to a Hudson Bay fort on the eastern edge of the Great Slave Lake. All this while travelling across some of the most inhospitable terrain on earth.

One must also not forget Royal Navy sailors were trained and accustomed to living onboard their ships and lacked the necessary skills and experience to travel light and fast while living off the land, like the Inuit.

They must have hauled the three boats some 24 kilometres to Victory Point. Here Lieutenant Irving was assigned to fetch the ‘All well’ note left a year earlier by Gore and Des Voeux in a cairn a few kilometres distant. Crozier dictated a new message to Fitzjames, which he scribbled around the margins of the earlier one.

To lighten the boats, a large amount of material was discarded at Victory Point. They then travelled for a further 80 kilometres down the coast where one of the boats was left behind, possibly as shelter and to further lighten the load. Here the party split with those strong enough continuing towards Back’s Fish River and others too weak or unwilling to attempt this long hazardous journey to the south, either remained to die at the abandoned boat or staggered back to their ships.

The last survivors stumbling to the Back’s Fish River crossed the strait, thereby discovering the North-West Passage, not that this would have given them any satisfaction because of their desperate condition. Several bodies were later discovered at Starvation Cove on the mainland a short distance from the Back’s Fish River estuary.

According to Inuit oral tradition, a handful of men retraced their steps to the ships where they might have survived a fourth winter (1848-9) before leaving their ship for the last time, probably to hunt for fresh meat, but were never seen again. On 24 June 1879, a small expedition of the American Geographical Society led Lieutenant Francis Schwatka discovered an open but well-prepared grave, seemingly that of Lieutenant Irving. Irving was the same officer who had been assigned to fetch the ‘All well’ note left a year earlier by Gore and Des Voeux. Although the grave had been despoiled by the Inuit while searching for useful items, it could only have been prepared by men who had already returned to their ships.

Only the very earliest rescue expeditions would have been able to save any survivors. Because of the icing of the Peel Sound and the failure of the Franklin Expedition to leave clues of its route, help finally arrived but eleven years too late.

The Hunt for Erebus and Terror

Over the years, various individuals and groups studied the evidence, developed their own theories, and undertook searches for the two ships. Finally, in 1992, the Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada designated the wrecks of HMS Erebus and HMS Terror as a national historic site to protect them if they were ever found. This together with a 1997 agreement with the British government gave Parks Canada a role in finding and protecting the ships.

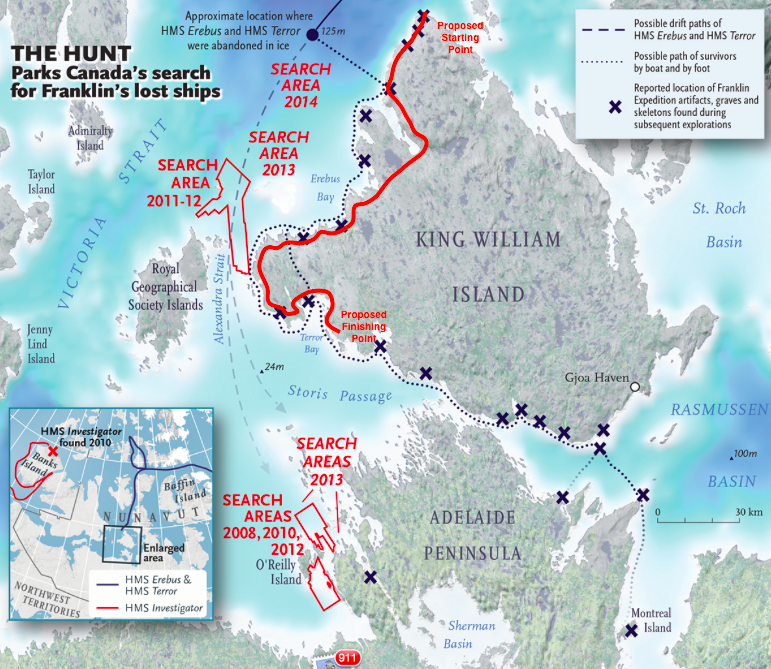

Where the initial searches for Erebus and Terror took place (www.adventurescience.com)

In 2008, the Underwater Archaeology Team of Parks Canada supported by a variety of collaborators, began a new multi-year series of modern searches.

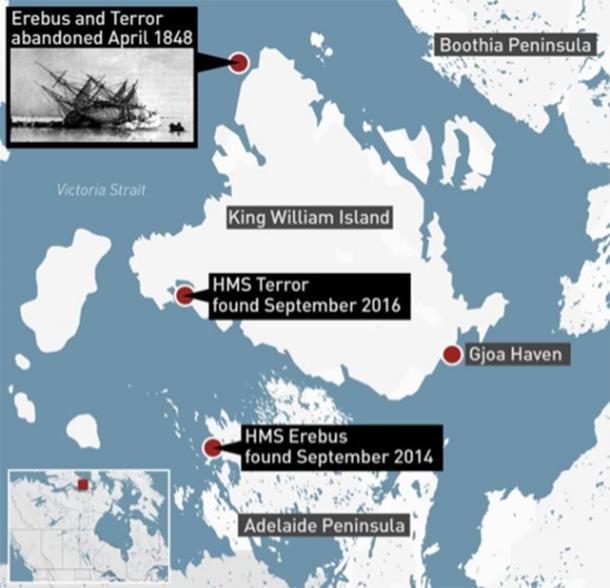

Finally, at a press conference in Ottawa on 9 September 2014, then Prime Minister Stephen Harper announced that one of the Franklin Expedition’s ships had been found. A few days later it was confirmed that she was indeed the Erebus.

In 2016 the Terror was also discovered at a depth of 24 meters, ironically at a place named Terror Bay.

Erebus was discovered much further south than anticipated, although Inuit oral tradition maintained one ship was last seen near an area called Utjulik, which is about where the wreck, submerged under 11 meters of seawater was finally discovered. So close to the surface that her masts if they were still erect would stick out.

By 2019 a multitude of artifacts have been recovered from the Erebus. According to Smithsonian Magazine, Parks Canada’s underwater archaeology team found over three hundred and fifty artifacts, including wine bottles, personal items, cooking and dining supplies. A recovered hairbrush with strands of hair still attached may offer clues to the men’s diet and stress levels.

There seems to be no intention of raising the ships but archaeological research and work on Erebus have been prioritised as she is at a shallower depth and more vulnerable to deterioration.

Where the sunken wrecks of Erebus and Terror were located (www.ancient-origins.net)

For the Canadian government it was not only a major archaeological discovery, it was also a matter of geopolitics. Because of global warming the hitherto iced up Arctic channels and passages might soon become navigatable with the North West Passage becoming an important channel for seaborne trade and communication. It was time to remind the world that the ships sank in Canadian waters.

Drone image above the wreck of HMS Erebus (Parks Canada’s Underwater Archaeology Team)

No doubt, the secrets that have remained hidden below the Arctic seas for so long will finally be unravelled and those interested in the fate of the lost Franklin Expedition will follow this unusual account with bated breath.

The South African connection

Readers may well wonder whether there is any connection between this British naval expedition and South Africa, and somewhat surprisingly there is.

Both the Erebus and Terror docked at the Simonstown Harbour en route to their exploration of the Antarctic and some of their officers used the opportunity to visit the nearby Constantia vineyards.

Sir John Franklin while serving as Lieutenant Governor of Van Diemen’s Land (Tasmania) had such serious disagreements with his Colonial Secretary John Montagu and other prominent citizens, that he (Franklin) was dismissed from his post in 1843. John Montagu who referred to Franklin as the ‘petticoat man’, because of Franklin’s strongwilled and overbearing wife Lady Franklin, was appointed Colonial Secretary of the Cape Colony in 1842, where he remained until 1852. He then departed on fifteen months extended leave to the UK to recover his health. Unfortunately he died in November 1853 from a chronic obstructive lung disease before he could return and lies buried in the Brompton cemetery, London. The little Western Cape town of Montagu established in 1851 was named in his honour. If it had not been for this quarrel who knows, perhaps Franklin would have been promoted to Governor of the Cape Colony and there might even have been a village there called Franklin!

About the author: SJ De Klerk held many senior positions in HR during a distinguished career in the private sector. Since retiring he has dedicated time and resources to researching, exploring and writing about South African history.

Sources

- Beatty O. & Geiger J. Frozen in Time. The Fate of the Franklin Expedition. Bloomsbury, London. 1988.

- Canning J. Editor. 100 Great Adventures. Odhams Books, Middlesex. 1969.

- De Kock W. J. Hoofredakteur. Suid-Afrikaanse Biografiese Woordeboek. Tafelberg Uitgewers, Kaapstad. 1976.

- Palin M. Erebus The Story of a Ship. Arrow Books, London. 2019.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.