Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

The exploitation of convict labour at the Cape during the Colonial era is closely connected with the work of John Montagu, Colonial Secretary for the Cape 1843-53. Montagu began his career as a colonial administrator in 1834, when he was appointed Colonial Secretary to Van Diemen’s Land, later known as Tasmania which, at that time, was one of the largest penal colonies operated by the British. There he gained a reputation as a brutal administrator and, after a disagreement with the Governor, Sir John Franklin, accepted the post of Colonial Secretary for the Cape, which he held from 25 April 1843 until just before his death in 1853. He was a staunch Anglican, and it is obvious that many of his policies towards convicts were firmly grounded in the puritan belief that correction ought to be brought about through the mixture of a protestant work ethic and religious proselytizing.

On 18 December 1843 Montagu was ordered by Governor Napier to visit Robben Island, for the purpose of “inquiring into the working of the convict system at that penal station”. As a result he put forward a plan which would consolidate the various mental institutions and lazaretti of the Colony upon the island, and would remove the major part of its convicts to work camps upon the mainland. Following the experience he had gained in Tasmania, it was Montagu’s intention that no convict should be detained upon the island “whose crime, conduct and character do not require a more severe degree of discipline and punishment than that which is observed at the convict road station”. Instead convicts were to be removed from their places of incarceration, whose upkeep was a drain upon the fiscus, and placed into work camps where they were expected to engage their labour, for free, on road building and maintenance projects.

In 1844 Montagu’s plan was accepted, and the removal of the chronically sick, lepers, lunatics and paupers to Robben Island was completed by November 1845. By 1857 there were about 720 convict camps scattered about the Colony. These were housed in temporary barracks, capable of being easily dismantled and moved to new locations as the need arose. After working hours, convicts were given basic schooling, with a heavy emphasis upon religious education (De Villiers 1971). However the larger of these camps also housed non-convict labourers, as well as their supervisors, and it is apparent that a number of additional facilities were included for their benefit, such as the use of a postal establishment. At minimum, this service would have been necessary for the engineer in charge to forward his weekly reports to Cape Town, but must have included the Master of Stores, whose need to place orders from Central Stores for provisions, tools and necessary equipment would have been a constant factor in the running of a work camp. .

From the outset of his arrival at the Cape, Montagu propounded that the establishment of an efficient road infrastructure for the Colony would open up communication and trade with the interior, and was thus an important precondition to its economic development. To achieve this, he needed a source of cheap labour and, given the depleted state of the Cape treasury at that time, convicts were seen as a logical solution to his problem. In this work, Montagu had the benefit of the support of two skilled road designers and land surveyors: Col Charles Michell and Andrew Geddes Bain.

Michell was born in England in 1793, commanded a brigade during the Napoleonic wars, fought at the Battle of Waterloo, and subsequently became Professor in the science of fortification at the Royal Military Academy, at Woolwich. In 1828 he was appointed the Colony’s first Surveyor-General, Civil Engineer, and Superintendent of Public Works. He was a brilliant architect, who is credited with the design of many important buildings at the Cape, and played a leading role in the planning and construction of a number of its roads. He retired in 1848 when he returned to England on pension. Bain was an equally multi-talented personality. Initially he trained as a saddler, took part in numerous trading expeditions into the southern African interior, wrote popular verse, and in 1836 was attached to the Royal Engineers. A natural, if untrained engineer, he constructed a number of military roads and passes on the eastern frontier, before undertaking a pioneer study of southern Africa’s geology and making several important fossil discoveries (SESA 1972).

Of the 720-odd convict camps believed to have been in existence during the 1850s, only twenty-two of these are known to have incorporated a postal facility as part of their establishments. This means that the other seven hundred camps were either too small to warrant a post office in their own right, or did not have an administrator of sufficient seniority to be entrusted with the running of a post office, or were located in the vicinity of an existing postal establishment. Although the majority of these camps probably fell into this category, it must be assumed that at least some must have enjoyed equal standing with the 22 listed here, and must therefore have had access to a postal service in their own right. If this was indeed the case, then no direct record of their establishments has been discovered to date.

The position of postmaster on a convict station usually fell to the Master of Stores, who was issued with “an obliterating stamp” to process postal matter. At least two such instruments have been documented to date: Wagonmaker’s Valley, which used the octagon numeral 15, and Howison’s Poort, which used a barred triangle obliterator. Being dumb, these could easily be transferred from location to location without necessitating a change of name or the expense of providing their postmasters with an engraved office date stamp. A similar policy of “wanderstempels” was also employed subsequently by the Cape GPO for temporary post offices in Basutoland and on the Kimberley diamond fields, and may have also been applied to the Cape’s Field-Cornet’s Posts.

One clue to the presence of additional convict station post offices may lie with the existence of a number of postal establishments during the 1849-74 period, which were listed as agencies, but which were quite obviously run by field-cornets. These establishments were listed in the Civil Establishment Blue Books from 1849 through to 1874, when all reference to them vanished from Post Office lists. Many of them were short-lived; had a penchant to disappear from the Blue Books, and then mysteriously reappear for a year or two only to vanish into oblivion; or to change their names at short notice, often two or three times within the short period of five years.

This is not the behaviour expected of a Field-Cornet’s Post, which was usually of a much more permanent nature, but would be consistent with an establishment given to impermanence, and removal at short notice, such as a road crew. Not all of these convict stations would have been large enough to warrant the appointment of a dedicated postmaster, nor, for that matter, would they have supported a thriving postal business, given the levels of literacy existing at that time. It is feasible therefore, that the collection and delivery of mails to temporary road camps would have been charged to a local official, whose duties already included the provision of a rudimentary postal service to isolated farm homesteads.

Given all of the above, it now appears probable that the series of seemingly irrational movements of postmasters, the unpredictable appearances and disappearances of post offices and their staff, and the endless changes of names, locations and divisions which blight the Colonial listings, were not the result of indifferent documentation, bureaucratic incompetence or the impermanence of staff. Rather, it can now be argued that many of these were temporary post offices which were attached to the nearest existing field-cornetcy, on a short-term basis, to service the needs of convict labor camps. The formation and location of such camps would not have been subject to Post Office planning, but would rather have been ordered by the planning needs and functional work requirements of the Public Works Department, leaving the GPO to passively document such information as the PWD saw fit to pass on to them.

To date only 24 postal establishments have been positively linked to convict labour camps, and little is known of the service provided them by the Post Office. Even then, this information is not entirely reliable, as many of the dates of opening and closing of their postal establishments do not correlate to the dates of appointment of the postal officials concerned. This is obviously an area of investigation which warrants the future attention of researchers, and the assistance of colleagues will be most gratefully accepted.

- Bain’s Kloof, Worcester - 1 June 1847 to 1852

- Berg River Convict Station, Paarl - 12 April 1853 to 24 February 1854

- Bird Island, Port Elizabeth -1 May 1872 to 1873

- Blanco, George - 4 December 1851 to Union

- Boontjes River Convict Station, Alexandria - 1860 to about 1866

- Breede River Convict Station, Worcester - 31 December 1852 to 30 January 1854

- Buffels River Convict Station, Namaqualand - 30 September 1867 to 1870

- Doornnek, Boontjes River, Alexandria -1867 to 1876

- Garcia’s Pass, Riversdale - 1880 to 1882

- Gydouw Pass, Tulbagh - 1 April 1866 to 1867.

- Howison’s Poort, Albany - 31 December 1856 to 1859

- Katberg, Stockenstrom - 25 March 1862 to 31 December 1878

- Lichtenburg Convict Station, Paarl - 24 February 1854 to 25 March 1856

- Michell’s Pass Convict Station, Worcester - 30 January 1854 to 23 December 1855

- Mostert’s Hoek, Stellenbosch - 16 November 1846 to 31 May 1847

- Nieuw Kloof, Tulbagh - 27 December 1858 to 1868

- Paarde Poort. Uitenhage - 19 November 1860 to 1878

- Pakhuis, Clanwilliam - 1 February 1862 to 1871

- Piquineer’s Kloof, Malmesbury - 24 June 1857 to 1858

- Vlugt , or De Vlugt, formerly Welgelegen - Post office opened as Welgelegen on 18 May 1859

- Wagonmaker’s Valley, Worcester - 1846 to 31 May 1847

- Winterhoek Convict Station, Tulbagh - 3 October 1860 to 1861

- Yzer Nek, Knysna - No postal establishment known until January 1885

- Zuurberg Convict Station, Somerset East - 6 January 1849 to 1859

To the best of my knowledge, the convict labour system is one of the last aspects of colonial society that researchers in this country have yet to cover, and once the locations of these camps can be established research by other disciplines, such as archaeology, may follow. This short article is being offered in the hope that others in the field who have stumbled upon references to Convict Stations during the course of other research, will be able to contribute such snippets to the general data base.

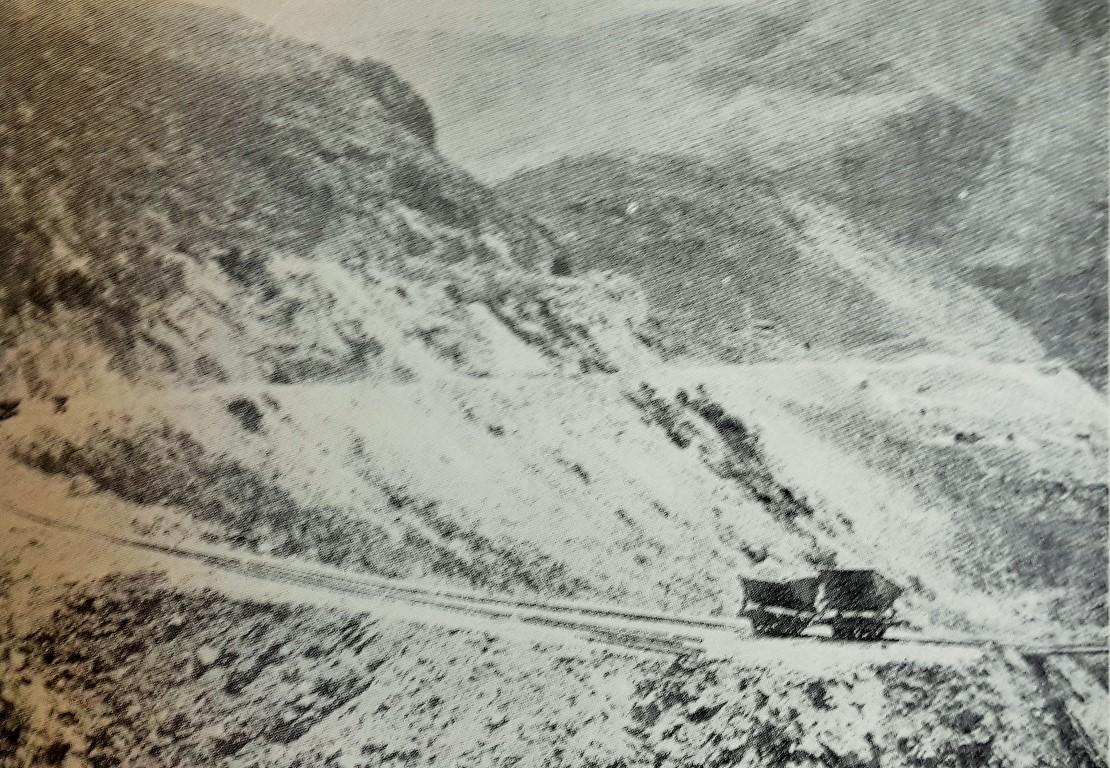

It is also worthwhile noting that the majority of convict stations listed above are linked to the construction of mountain passes. To draw a military analogy, the construction of a road can be likened to a military campaign. The general reading public is generally more interested in the drama of battle than in the skirmishes, the hours of training or the square bashing that precedes it. Similarly, the building of mountain roads and soaring bridges is more likely to capture the attention of the public than the setting out of the road over a plain, or the laying in of provisions and labour that precede the final climb over a mountain range. Yet, the location of such road camps may well provide the key to the organizational issues that had to be overcome by road engineers of that time.

Besides, not all convict labour was linked to road building, and a number of important colonial structures and urban buildings were erected by the use of convict labour.

Franco Frescura - Professor and Honorary Research Associate, University of KwaZulu-Natal. He is currently engaged in the documentation of the historical built environment of Durban, including aspects of its oral history and material culture.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.