‘Then and Now’ books of photographs are becoming popular. I recently reviewed Vincent Van Graan’s Cape Town: Then and Now (click here to view). There is an appeal in matching old photographs that open a window on the past and then to return to the exact same spot to see the same place as it is today. What has changed and what has remained? It is a form of heritage treasure hunting. Old photographs are a valuable documentary source to provide information about streetscapes, old architecture, panoramic views etc. Such photographic books are a source of comfort and continuity between the past and our time and make that past seem much less a “foreign country”.

Now Yusuf Agherdien’s South End, Then and Now has dropped onto my desk. It too is an item of Port Elizabeth (or is it more correctly termed Nelson Mandela Bay Municipality?) local history but more specific, more local and more purposeful than the Cape Town Van Graan book. This is a delightful book of photographs of an area of Port Elizabeth that suffered from the Group Areas Act, apartheid social and racial engineering. The bulldozers arrived to up end communities and implement unjust laws in the name of apartheid modernization, town planning and sorting people out according to race and government decree. This is a book that looks for a forgotten history through images and seeks to address past wrongs.

South End was the "District Six" of Port Elizabeth, a vibrant cosmopolitan community. It comprised “English and Afrikaans speaking Caucasians, Malays, Coloureds, Indians, Chinese , Jews and a mere handful of Africans”. It had churches, temples, mosques. It offered its residents a bioscope, dancehall, park, cemeteries, retail shops, doctors, airport, railway station, medical clinic, hospital, post office, schools, police stations and much more besides. It was an integrated community with a sense of belonging and completeness. It was a way of life.

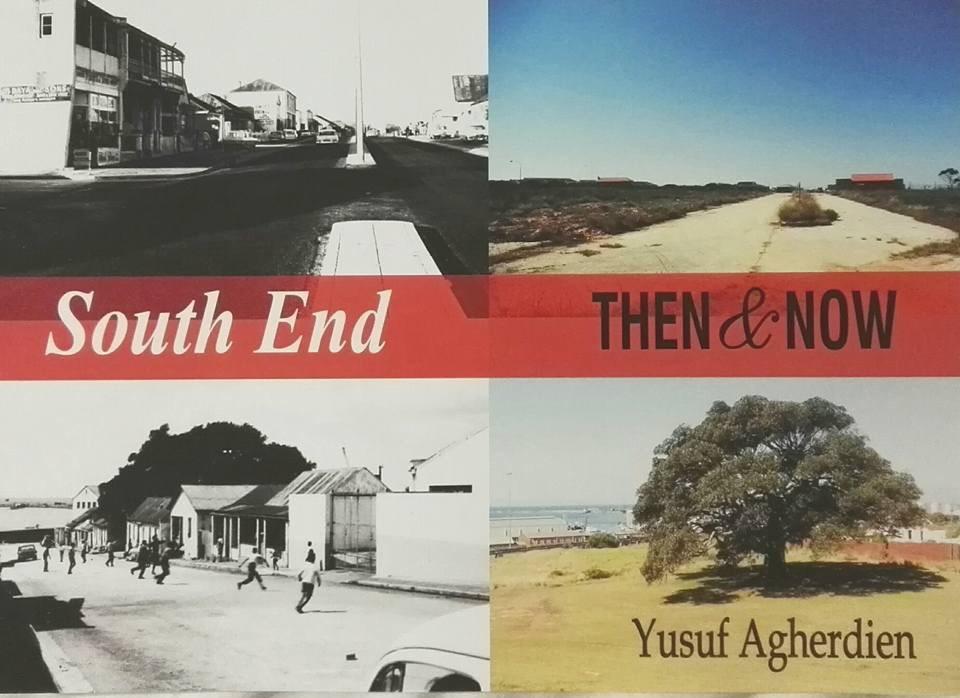

One of the 'Then' shots from the book cover

It must have grown organically with the settlement and growth of Port Elizabeth (named for the deceased wife of Sir Rufane Donkin, the first governor of Port Elizabeth in 1820 to 1821) from the time of its origin in 1820. Port Elizabeth became the second port of the Cape Colony. Donkin was the British military man charged with organizing the 1820 settlers whose task it was to settle on the Eastern Frontier, a community to form a buffer zone against the local people of the area living beyond the Kei. Here too was another bit of social engineering.

The Group Areas Act was passed by the Malan government in 1950 and was to be implemented from that year. Of course sorting people according to race and colour and finding them accommodation in new sometimes barren remote new residential towns, settlements, townships, and suburbs took time and investment capital. By 1965, the enterprise to demolish South End had begun. This too took time and some people resisted by staying put and not moving. Short term plans for renewal and redevelopment took on long term time horizons and created wastelands that lay there.

This particular publication captures in photographs the Then of South End dating from approximately the year 1970, there was still enough of the old area to document. It contrasts sharply with the photographs taken by Agherdien in 2013. Agherdien was lucky in finding the photographs of the late Ron Belling, a photographer and an artist of the old South End. The book is also a homage to Belling. Agherdien ‘s family came from South End. Three generations were all born in the same house. His family was forced to move and move they reluctantly did to Salsonseville, but only in 1973. He returned in 2013 to stand in Ron Belling’s footprints and retake the same photos. His objective was to understand feeling and emotion and to recall in memory and image a way of life that disappeared fifty and more years ago.

Today there is a South End Museum, housed in the old Seaman’s Institute (it stood vacant for 30 years). Agherdien has made it his life’s work to capture history, to tell the story of apartheid and what it meant at a local level and in a sense, to hold accountable “someone” for the loss. Agherdien wants to give his children a vision and a history, a pride in their family past and through this book he shares it with all South Africans. He has mounted exhibitions and produced books.

There are two maps of South End as an Allotment area for the City of Port Elizabeth in 1970 and a map of South End 2013 prepared for the Nelson Bay Municipality. It is almost impossible to relate these two maps to one another. I recognize a railway line and a couple of roads but the landscape has been re-engineered. The final images are of aerial photographs, one is of South End in 1939 and the other is of the same aerial view in 2013.

The pages of photographs are interspersed with the memories of people who lived in, for example Rudolph Street, South End. The memories come tumbling out. And the images are balanced by the written word that tells of family stories and life of the forties, fifties and sixties.

In paging through this book of photographs, one is struck by the contrasts. There were houses, factories, idiosyncratic homes of people, little homes, some quite substantial facing onto streets where children could play. Today the views are of wide spaces, underutilized or barren land, no organic street life, demolished open areas, bigger street lamps, and wider roads meant for cars, new planned houses. Where are the people? St Peter’s Church, a beautiful stone church is just a ruin. High rise blocks rise in the distance. The old water tower for the Forest Hill residential area is gone. There are some facades of old houses on Walmer Road still there, but they have been gentrified. The south End Clinic has been renovated and become residential units. The fingerprint and echo of the past comes through only in the surviving mosques such as the Rudolph St Mosque (Masjied Ul Abraar).

Of course time moves on, then “development happens”, but there is pause for reflection that a vibrant community was destroyed and shifted to a point of disintegration. There is no community left. Our town planners and social engineers should be reflecting on whether the improved landscape is actually an advance. Heritage is decontextualized. Today to see South End as it was you need this book or a visit to the South End Museum. For further discussion have a look at this Guardian article.

One of the 'Now' shots from the book cover

Any criticisms? Agherdien tells the story through personal stories but there needs to be a framing text to provide context and explain the Group Areas Act. The history of South End needed to be related to the wider history of Port Elizabeth. I would have liked to know more about the economics of the process – who financed removals, who paid for new houses, what happened to title deeds? It seems to me that there simply was not the investment capital for property development on the scale the state planners anticipated; poverty could not be magicked into prosperity. The capitalist system does not quite work the way in which the ideologues anticipate. Why should South End matter to Port Elizabeth? But overall the book is about the recovery of history and memory and for that I salute the author.

End note - The only connection I have to Port Elizabeth is that I recall that my grandmother was buried at the Walmer Cemetery in about 1943 and my mother worked for a time at the Firestone Factory when she cared for her sick mother. My family never put down roots in Port Elizabeth, but I feel that an important part of local history has been handed to me and I thank the South Enders for making their history mine.

2017 Guide Price: R275.00. Available from the Museum - Tel: +27 (0)41 582 3325 | Email: adminsem@telkomsa.net

Kathy Munro is an Honorary Associate Professor in the School of Architecture and Planning at the University of the Witwatersrand. She enjoyed a long career as an academic and in management at Wits University. She trained as an economic historian. She is an enthusiastic book person and has built her own somewhat eclectic book collection over 40 years. Her interests cover Africana, Johannesburg history, history, art history, travel, business and banking histories. She researches and writes on historical architecture and heritage matters. She is a member of the Board of the Johannesburg Heritage Foundation and is a docent at the Wits Arts Museum. She is currently working on a couple of projects on Johannesburg architects and is researching South African architects, war cemeteries and memorials. Kathy is a member of the online book community the Library thing and recommends this cataloging website and worldwide network as a book lover's haven.