The first thing this book taught me was the meaning of Iziko (it means hearth in Xhosa). The Iziko organization (from its website) is a cluster of fourteen Cape museums covering natural history, social history and a number of art collections. Any history of the august National Gallery, located in the Gardens in the heart of Cape Town, needs to start with the radical changes that hit the museum world in 1996 when the new government decided to consolidate previously independent institutions in the Cape and hence create this “Southern Flagship” of museums, all under the administration of the Department of Arts, Culture, Science and Technology. Iziko seems in this context to be more of an umbrella than a warming hearth, but clearly there is a strong government hand at work. Perhaps it all made sense administratively, but there is a problem when artistic, gallery and museum independence becomes subjected to essentially political control. New nationalisms and new ideas about using state controlled cultural organization to define culture, taste and nation building makes for some discomfort. Of course this is nothing new and as pertinent today as it was in the past.

Debates around these issues bring to the fore the key questions about what is art, what is the distinction between different types of art objects (e.g. a painting versus a craft textile), who is this art for, who shapes taste, who should shape taste, who should be the custodians and curators and, most significantly, where should the money come from to buy the art and build the collections of the future. Perhaps even more fundamental, should there be a national collection housed in one place in a national gallery? What is its influence and what influences the national gallery? Should the art museum reflect taste or history? Should a national gallery collect and exhibit art narrowly defined as paintings and sculpture or should it extend into the applied arts? Where do the classificatory boundaries lie? These questions are among the themes and threads that run through this fascinating book.

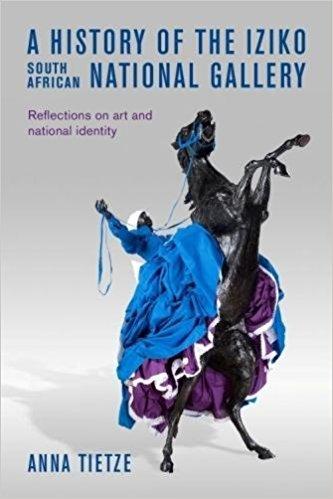

Book Cover

This study is timely and prescient and should stimulate further debate at a time when we have the extraordinary case of UCT and its public art and sculpture. It started early in 2015 with the the desecration of the Marion Walgate statue of Cecil John Rhodes on the upper campus of UCT, the fierce reversals of fortune of the public legacy of Rhodes. The Fees Must Fall activists of 2016 at UCT brought the destruction of 23 works of art. These students were on the rampage to eiminate the visible presence of a colonial white South Africa. It was a bonfire of note and received national and international media coverage. This was followed by UCT’s own self censorship of what art should or should not be displayed in its anxieties about the sensibilities of young viewers. Then there is another kind of challenge that stems from the opening of the private Zeitz Museum of Contemporary Art Africa (Zeitz MOCAA). The National Gallery is in difficult terrain.

Tietze puts her finger on the problem. This is the moment when the status, purpose and nature of art in contemporary South Africa are contested. It did not only happen in Cape Town but impacted everywhere. Libraries, museums and galleries were most under threat because they house past collections assembled for and by a completely different society. Even before 1994 public galleries were forced to come up with some answers about their own attitudes to the post-colonial nation, redefining African art. They began to ask and address what passes for appreciated and acceptable exhibition. What is the role of the art curator and how should works that may well include some installation art be displayed.

Tietze’s objective is to delve into the 150 year old history of the Iziko South African National Gallery. She aims to get a grip on context and use background as a possible guide to the future. Art specialists going forward in the face of both iconoclastic attacks and affirming outreach to new audiences need authority and here is one such possible source. When one section of a society attacks the art of another, art becomes a battleground for social tensions and pressure points that explode in a proxy war. Art is instantly political. This is a fascinating study of one institution within the current South African social cauldron.

Tietze’s excellent study is at first glance aimed at an academic readership and will appeal to those who work in the field. It is well researched, with careful footnoting (the footnotes are every bit as interesting as the text and there’s many a gem of a quote to be found in the small print), a comprehensive bibliography and a professional index. Once again UCT press has produced a quality study that ought to be read by anyone with more than a passing interest in galleries and museums. If you visit a museum to be educated, edified or entertained this book will set you thinking. It raises questions about why and how an important national gallery sets about building a collection, working to acquire new works and at the same time preserving old collections. Today, to attract people who are the life blood of these institutions, galleries and museums must be all things to all people and must educate, entertain, feed and provide a shopping experience. How well they perform these varied tasks then turns the gallery from an elitist place of scholarship into a popular adventure for mass culture. How far though should popular become populist?

Iziko National Gallery is hardly a ‘national gallery’. It originated as very much a Cape Town institution along with the Library and the Musuem. For South Africa after 1910, a “national gallery” in Cape Town was always something of a contentious point in a country where there were there were three capitals; and a further excellent collection of national stature assembled by Florence Phillips for the Johannesburg Art Gallery. Incidentally, Phillips also had ideas about how a Cape Town Gallery should be shaped and developed and that it should have something of the appeal of the Victoria and Albert Museum in South Kensington, London. Perhaps the idea of a national gallery is only of significance where international comparisons are made and one looks to London, Berlin, Washington DC or Paris for parallels in national collections. But a national gallery drives to the heart of the matter about a national identity and purpose of such an institution at least since the making of Union in 1910. Its task then was to shape and mould a unified South African identity. Whose “hearth” should it house, whose heart should be warmed? There is an unintentionally hilarious footnote (page 206, footnote 54) quoting a 2013 Iziko press release: “the interior of the Iziko South African National Gallery is as warm and familiar as a Xhosa mud hut”. National institutions risk falling under state control and as such invariably have the unfortunate fate of reflecting the political agenda of the day.

The state too can be open handed in their financial support or regard a gallery as low on a list of pressing social priorities. This study tracks the colonial era (strangely having the dates 1875 to 1930), the seemingly more enlightened era of the thirties and forties, the post war years from 1948 to 1972, the seventies and eighties efforts that brought political crisis during the apartheid years but were also years of protest. The final chapter addresses the changes and transformation during the last thirty years but also a time when Picasso and Trechikoff revealed new opportunities and raised old debates. There were and are dangers in the selection of art for the nation, its display and the curatorship of exhibitions which has an onus of new interpretations for a new generation. There are parallels that could have been drawn with other national institutions such as the concept of a National Library in Cape Town versus a State Library in Pretoria.

A national gallery needs a strong minded, educated, intelligent and visionary leader with excellent connections, a creative flair, independent judgement and immense charm to navigate difficult territory. Again this is no more true today than it was in the past. Such a leader is the director and this book is effectively the story of the succession of directors from the early days when the director was an honorary appointment (an example being the not uncontroversial Edward Roworth) through to the relatively late appointment of the first full time professional director (John Paris) to the most recent appointment (again the not uncontroversial, Riason Naidoo). So one reading of this book is to keep a critical eye on how each successive director juggled the different agendas of his or her era. The subtext is about decision making by directors and their successes and failures. The directors, Edward Roworth, John Paris, J W von Moltke, Matthys Bokhorst, Raymund van Niekerk, Marilyn Martin, and most recently Riason Naidoo were all people who shaped curatorial and acquisitions policy and had to engage with practical approaches and solutions to the artistic and political issues of their time. My hat off to Marilyn Martin for her management, transition and management during a long eighteen year tenure. This book is the story of the response of a succession of directors to the central question of social responsibility. How should a national gallery serve the cause of the nation’s art. One interesting theme is the question of how attitudes towards international connectedness matter to ensure that this particular gallery in Cape Town does not become a provincial outpost of empire. The director who jumps to the prevailing fashions and specific agendas of ignorant politicians or poo clutching students will fail. Tietze neatly sums up the challenge for the future in an almost throw away sentence at the end of chapter 5 when she says: “In the coming years, Iziko Museums and the Gallery will need to maintain an independence of vision and position themselves as cosmopolitan international institutions.”

This is a recommended academic study but a book that is accessible and interesting because it raises these critical questions around social purpose and identity and examines the way in which the South African National Gallery has understood its function and how a succession of influential directors sometimes led the way with flair and soared and sometimes blundered into controversy and crisis. This is far less a book about artists than about management, art policies and directors.

Another theme that is worth close study is that of the management of the donors and donor collections. The National Gallery has always depended on gifts from old masters to the landscape genre. Despite being the National Gallery, funding and money to finance acquisitions in the face of rising commercial prices for either good or popular art, has meant that donor support has been significant in all decades. Funding always seems to have been in crisis. Here then is the story of the varied collections such as the J B Robinson collection, the Abe Bailey bequest, the Alfred A de Pas collection, the Lady Michaelis gift of old masters, the Davis gifts of British art. These donations were not without controversy; the type of art collected and popular in one generation could become passé and dated by the time the original collector gifted his collection or left a bequest in a will. What happens when too many paintings, not all of them regarded as top quality, arrive and need to be placed on display? The display of collections carries a cost.

A question arises - why do donors give their work to the nation? How do you reconcile the morality of the making of money by the Randlords (it opens a Pandora’s box to talk about collections acquired from wealth made on the back of very cheap labour - don’t even go there unless you want to really debate the morality of the money and art nexus) and the spending of money on art which is then given to the nation? Why would a donor give his or her art to a public gallery when there are risks? While Tietze covers the scandal of Roworth’s decision to sell works of art from the permanent collection in 1944 in some depth, the appalling saga of the Labia Museum at Muizenberg and the court case that followed is glossed over. This is central to understanding the Robinson collection.

On the other hand, how can more private collectors be enticed to leave their collections for the greater good of society? A useful probe could have been extended into the motives of the donors. Why has South Africa not made more effective use of tax concessions in the collection of national art? Is immortality being bought through a collection, particularly when a condition of a bequest is that the collection should remain together or could not be sold? The story of the Lycett Green collection, which was on loan to the National Gallery until 1954 and the fall out with director Paris over attributions is entertaining and surely holds some valuable lessons in how to manage (or not manage) potential donors. The Lycett Green debacle reminded me of the saga of the Gilbert Collection of London and Los Angeles, which because of challenges, disputes and changes in mind, floated between London (the collection was best displayed at Somerset House but then drifted into an amorphous space at the Victoria and Albert) and the Los Angles County Museum of the Arts ( LACMA).

There is some coverage of the construction and the architecture of the National Gallery. I would have liked more to have been written on this, after all it is an iconic building dating from 1930 located in the heart of Cape Town, magnificently sited below Table Mountain. The setting is breathtaking. The National Gallery was designed by John Clelland and Frederick Mullins of the Public Works Department working with Franklin K Kendall, with funds provided by the Government and the Cape Town City Council. Kendall (dates 1870-1948) needs a much fuller coverage of his involvement and the politics of the architecture is itself a fascinating subject. Kendall was the senior partner of the firm Baker and Kendall and the heir to the Baker tradition in Cape Town. The National Gallery reflects this legacy. Unfortunately the grainy old small, black and white photographs of the National Gallery and its interior are poor and hardly bring out the best features of the site, building and its magnificent setting.

Magnificently sited below Table Mountain (The Heritage Portal)

An area that has not been studied but could have featured in greater detail is finance and the economics. It is an underlying theme but needs more direct and fuller information. What was the precise budget of the Gallery? How was the funding split between salaries, art acquisitions and the administration. Art marches forward on its stomach and the broad brush sweep that funding was always perilous is not precise enough to know how well each director managed the financial issues. One needs finance to back scholarship, to mount exhibitions and of course to buy art. We need to know more about this delicate subject.

Finally there is also the question of where a national gallery with a limited budget stands in relation to new private initiatives, such as the Zeitz Museum of Contemporary Art Africa at the Waterfront. The official current line is for the Iziko Museums to promote African, now defined as essentially black heritage. Whereas the Zeitz Museum has an African continental wide vision and it has the funding to support a generous and wide acquisitions strategy. Is this new Waterfront initiative a threat to the National Gallery? The Iziko National Gallery cannot compete against such superior buying power. It has to look for an African identity and underpinning for its own collection means not only purchasing contemporary works of art but also filling past gaps and voids. However, it is being nudged in very different directions by new private players.

Haden Proud’s useful article 'Our National Gallery: The ‘Book’ of our Art?' is mentioned in a footnote, it is not listed in the bibliography. It is a quick read that gives another useful dimension (click here to view).

The quality of printing in this book is uneven with ink fading on some pages from black to grey. The cover of the book gives the work by Mary Sibanda (2010) pride of place (also featured as plate 21). There is an attractive section of 21 coloured plate illustrations but the black and white text illustrations are not appealing for a book that deserves top quality reproduction in all its aspects. Unfortunately, the look of the book may well consign it to the specialist readership but it warrants much wider appreciation.

There is no comment on the garden statuary. For example, two statues of Jan Smuts, former general and prime minister (1870–1950), are to be seen on Government Avenue. The one by Sydney Harpley is prominently position in front of the South African National Gallery.

Smuts Statue in front of the National Gallery (The Heritage Portal)

In summary, I found this study delivered in a scholarly and detailed manner on its task of reflecting on the history of the institution, art and the national identity.

Thank you to UCT Press / Juta AEA for providing a copy of the book for review.

Kathy Munro is an Honorary Associate Professor in the School of Architecture and Planning at the University of the Witwatersrand. She enjoyed a long career as an academic and in management at Wits University. She trained as an economic historian. She is an enthusiastic book person and has built her own somewhat eclectic book collection over 40 years. Her interests cover Africana, Johannesburg history, history, art history, travel, business and banking histories. She researches and writes on historical architecture and heritage matters. She is a member of the Board of the Johannesburg Heritage Foundation and is a docent at the Wits Arts Museum. She is currently working on a couple of projects on Johannesburg architects and is researching South African architects, war cemeteries and memorials. Kathy is a member of the online book community the Library thing and recommends this cataloging website and worldwide network as a book lover's haven.