Observatory in Johannesburg is one of those rare "hidden treasure" type of suburbs in Johannesburg, located to the north east of the city and spreading across the high ridges of the Witwatersrand. It is a suburb that takes full advantage of the koppies, panoramic views and rocky terrain. Established more than 100 years ago, there are many fine old heritage houses on stands between half an acre and a full acre. The core nodes of the suburb are the Observatory Golf course, (Johannesburg's oldest extant golf course) and the old Johannesburg Observatory with its familiar round domed observatory, the prominent Baker designed library, some heritage houses on the ridge and the many buildings of what is still an important scientific complex.

Observatory Ridge from the South (The Heritage Portal)

I should declare an interest as I have lived in the suburb for nearly four decades. When we bought our house on the other side of the valley, I never expected to put down deep roots here but the appeal of the suburb grows on one with its clean air on the ridges, fine views and lovely homes, and easy reach to most places in the city. This is a book to read if you live in the suburb or if you are interested in Johannesburg and scientific history.

Sometimes it takes a journey abroad to raise one's appreciation for "home sweet home". Last month I travelled to Argentina and came across an observatory in a spectacularly scenic part of the Andes, the Apimpa observatory, of the University of Tucuman. It to is on a high rocky ridge with spectacular view sites but of fine mountain country. Immediately I felt a sense of belonging as it recalled the observatory right here in our own suburb.

Books about local history are important because they are like a mosaic square which is both a work of art in its own right and at the same time is part of a greater whole of the fabric of society and the urban history of Johannesburg. This book documents the illustrious and extraordinary history of the Johannesburg Observatory, though this is a sort of summary name covering many specific name changes and changes in scientific purpose and direction over a century.

The significance of the Johannesburg Observatory lies in its contribution to South African science across the decades in multiple fields (in meteorology, astronomy, time keeping, scientific studies of driver fatigue, telecommunications research, rainfall research, lightning and in recent years a wide range of scientific and science education projects, under the auspices of various science based bodies and associations).

The author, Dirk Vermeulen is a professional electrical engineer and amateur historian of science and technology. Vermeulen was a key player in the development of the South African Institute of Electrical Engineers' historical section and, as the SAIEE has its headquarters at Innes House located at the old Johannesburg Observatory, the task of recording the history of the observatory site fell to Vemeulen. The first edition was published in 2006. My copy is the second edition published in 2012 (however a few typographical and editorial errors still remain).

The title Living Amongst the Stars is a brilliantly evocative title and reminds one that the ridges of the Witwatersrand in the early days on a dark night were the perfect place to study the southern hemisphere stars above the highveld. Clear cloudless skies and predictable rain patterns in a place, that in 1903 was still way out of town. Later of course the bright city street lights and suburban developments made the stars and planets not quite so easily visible. This book documents the significant role of Johannesburg in astronomical study, research and discovery. The author has done a superb job tracking down rare photographs, diagrams and letters and this adds an immediate appeal for the lay reader.

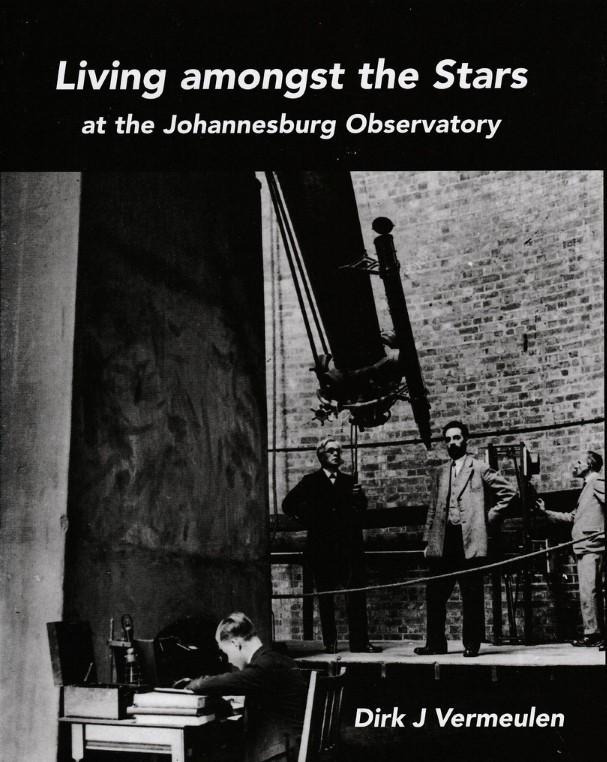

Book Cover

The book blends the personal stories of the great astronomers of Johannesburg and the specific scientific discoveries and advances in astronomy that constituted their work from the first decade of the 20th century until, what was then named, the Republic Observatory, closed in 1971 and some of the equipment moved to Sutherland. There were four Union astronomers who put the Johannesburg Observatory on the stellar map and achieved international reputations in astronomy. They were Robert Innes, Harry Wood, Willem Henrik van den Bos and William Finsen. From 1909 to 1965, the name of the institution evolved from the Transvaal Meteorological Department, to Transvaal Observatory, to Union Observatory, and finally to Republic Observatory. These were the decades when pioneering, extraordinary work was done.

Robert Innes (today remembered in the name of the main road though the suburb) was the eccentric man who shaped the Johannesburg Observatory. The principal legacy and founder status, was his, as he came to the Transvaal in 1903 to establish the Transvaal Meteorological Department and the observatory for meteorological, astronomical and allied subjects was established on land (eight acres) given to the Transvaal government by the Bezuidenhout family who owned the original farm Doornfontein. A condition of the gift was the making and maintaining of the road between Bellevue East and the Bezuidenhout farmstead and hence the origin of what became Observatory Avenue. Herbert Baker prepared the plans for the director's house (to become the Innes homestead) and the meteorological observatory on the ridge and the Baker building were opened by Lord Milner in 1905. Despite a fire in the 1980s that building is still there. Vermeulen has sourced some great photographs of the gala opening. The Baker building was the library but also the station that recorded temperatures, rainfall, lightening, cloud cover and earth tremors.

It was a logical shift to appeal for a telescope and for the observatory to become an astronomical centre for Innes to pursue his interest in double stars. Innes must have been a charming and determined man who purchased (and personally guaranteed) a nine-inch telescope. Then came the making of sky maps and photographic records of the southern skies. Perhaps somewhat confusingly Vermeulen has separated the scientific history (covering the telescopes acquired, and the scientific achievements) written up in two key chapters from the six chapters relating the biographical details of the astronomers of note. There was consequently some repetition of facts.

Finsen was the first and last Republic astronomer and retired in 1965. Thereafter there were two acting directors, appointed between 1965 and 1978, Jan Hers and JA Bruwer and the Republic Observatory had become the responsibility of the CSIR (the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research). By the mid 1960s, the writing was on the wall for closure of the Observatory. it was Hers who compiled the report that led to the decision to centralize astronomical work at Sutherland in the Cape and the Republic Observatory was officially closed in 1971. it was an enormously controversial decision and Vermeulen glosses over the controversy and criticism in a minor paragraph. More detail as to what happened and why the decision was controversial is to be found in the succinct chapter in The Astronomy of Southern Africa by Patrick Moore and Pete Collins (1977). Perhaps Vermeulen is too close to the events to give a critical assessment of a fraught period.

The section of the book I found most fascinating was the story of the work of the accurate setting of time and the move from relying on the Markham clock, in the city centre, to reliance on radio time signals, to the development of the Observatory Quartz clocks and it was Hers' achievement to construct these Quartz clocks giving high accuracy and stability.

The Markhams Clock (The Heritage Portal)

After 1972 the Observatory site was occupied by other CSIR bodies and Vermeulen covers the continuation of the tradition of scientific research in a descriptive chapter which also tells of the devastating fire at the Baker Library in the early 1980 (no precise date has been given). The final few pages summarize the history of various scientific societies and institutes and their location at the Observatory site. The Johannesburg Observatory is still the home of amateur astronomy in Johannesburg and today the National Research Foundation (the NRF) has as its mission the promotion of science, engineering and technology at the Observatory Science and Technology Site.

I recommend this book for the useful aerial view of the Johannesburg Observatory in the early 1990s, plus the appendices documenting the asteroids (minor planets) credited to the Johannesburg Observatory and lists the names of staff. There is a helpful reference section and a professional index. The one design feature that irritates is the banner sized print of the book's title on each page.

The Johannesburg Observatory has slipped into landmark and heritage status but this book serves well in telling the history of the science and the people who lived amongst the Stars. Certainly there is a case to retain the street names of Observatory that recall the roll of the suburb and some great men in world astronomy.

2016 Guide Price: Still in print and available from the South African Institute of Electrical Engineers, office in Observatory for R275

Book Details: Living Amongst the Stars at the Johannesburg Observatory, Dirk Vermeulen, publisher Chris van Rensburg publications, 2nd edition 2012. 134 pages, illustrated.

Kathy Munro is an Honorary Associate Professor in the School of Architecture and Planning at the University of the Witwatersrand. She enjoyed a long career as an academic and in management at Wits University. She trained as an economic historian. She is an enthusiastic book person and has built her own somewhat eclectic book collection over 40 years. Her interests cover Africana, Johannesburg history, history, art history, travel, business and banking histories.