Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

From the very beginning of the formal establishment of Dundee in 1882, the town was remarkable for the calibre of its inhabitants. Perhaps none more so than a young doctor and a young surveyor, who set off in 1884 for the unexplored “sea of land – land of water”.

The initiative was their own – without sponsorship from Government, the Royal Missionary Societies or the Royal Navy - they made and paid their own way. They were Dr Aurel Schulz MD and Mr August Hammar CE.

Over a hundred years later, the land that Schultz and Hammar traversed on foot, remains a land of adventure. They discovered this world in all its pristine glory.

Rumours of this magical world must have filled Hammar’s first years in Africa. He landed in 1879 and was sent to Rorkes Drift to map the frontier farms along the Buffalo river. He watched the battle of Isandlwana, from the heights of the Oscarberg. Unable to escape due to the approaching Zulu impi, that night he lay concealed on the hillside, watching the burning flames of the hospital building and hearing the frightful sounds of the battle below him. Signing on with Baker’s horse he fought throughout the rest of the campaign until after the battle at Ulundi when he returned to the burnt remains of the mission station to pick up the threads of his career. Round the campfires and talking to locals and passing adventurers, he heard many tales of grand adventure.

Site of the Battle of Isandlwana (Talana Museum)

The “old Dutch hunting road” of the elephant hunters climbed over the Helpmekaar and dropped down to Rorkes’ Drift. On the shoulder of hills above the drift at “Knostrope” lived Willie Adams, a renowned hunter. Beyond him lay the lands of the Vermaaks and du Bois brothers. Bands of armed 'natives' moved to and fro along the road bringing home their spoils from the Limpopo, Zambezi and Swaziland. Adams extended family included Piet Hogg, Rathbone and Vicar Brayhurst, all hunters, all with tales to tell, of wondrous sites and experiences.

Hammar, precise, artistic, slight of build met a congenial spirit in a Berlin trained doctor, Aurel Schultz, who had chosen the “boom” mining town of Dundee as his first practice. Schultz was a genial giant, 6’2 inches in his socks and with the strength of a young bullock and extremely likeable and jovial. He too, probably had his fill of hunters and adventurers’ tales, as he lived on “The Oaks”, a farm belonging to the Wades, yet another family of hunter/traders who been living along the frontier for many years.

The two men left Dundee quietly one autumn morning in 1884 in a two-wheeled cart, drawn by 12 oxen from Hammar’s farm, with Rudolf, a European cook and 3 native servants.

2700 miles and 10½ months later, they returned and settled back into their professions of doctor and surveyor.

What prompted them to publish an account of their journey 13 years later, was the outbreak of the Matabele Rebellion in 1896. A Dundee family, the Cunninghams were massacred in that uprising and the frontier town and the rest of Natal, were keen to have information about far-flung Africa.

“The New Frontier – A journey up the Chobe and down the Okovango rivers” (Heinemann, London 1897) was written by Schultz and illustrated by Hammar. A rare and extraordinary account of endurance and courage.

They left armed with 11 guns - Swinburne Henry’s, 4 elephant guns and a variety of shotguns and ammunition. Trade article for barter, blankets, beads, copper wire made up the bulk of their baggage, along with Hammar’s survey instruments and artists tools, a half dozen each of shirts and 4 pairs of moleskin trousers, and “nine pair of ammunition boots and woollen socks, which are the best footgear for work of this kind, also a couple of coats apiece.” Hammar wore a helmet and Schulz a “veld hat augmented by a Panama straw hat over which the veldt hat was drawn and fixed, with good ventilation holes punched through the sides, to allow the air to circulate freely over the head.” The 3 white men rode salted horses, whilst the 3 'natives' trotted alongside the oxen.

Ten days of steady travel took them to Pretoria, where plenty of advice was to be had from old hands. From Rustenburg, then a tiny village they set out for the Kalahari and the capital of King Khama of the Bamangwato at Shoshong. Although the expedition followed an established trader’s route, with hunters and traders moving along the route and cattle being driven to Kimberley, the unknown was a daunting thought, and the 3 Natal 'natives' deserted at the Limpopo crossing.

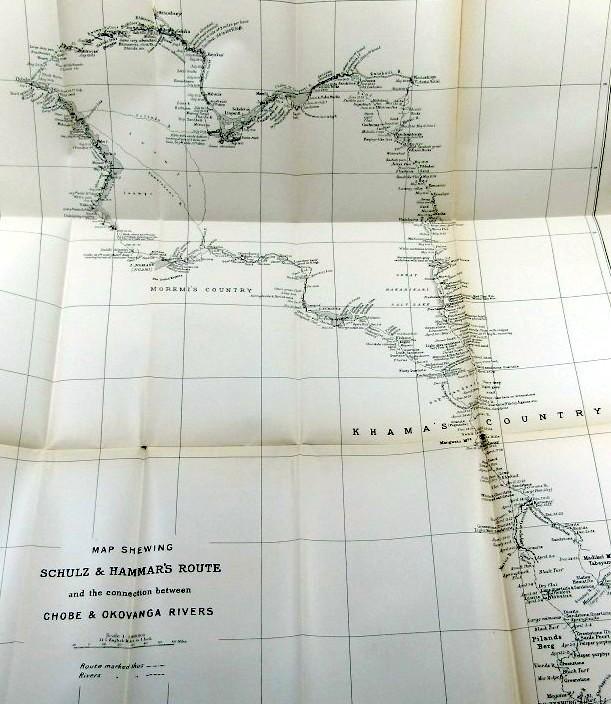

Chobe and Okovango map via Talana Museum

The 3 men slogged on, dragging their cart through the light sand and digging it out from the muddy river swamps. They marvelled at the vastness of the Makarikari salt pans, deplored the absence of game and hence food, on the Nata river, and rejoiced at the ample water in the Klamachanyana pools, but were dejected when they found that huge herds of elephant had drunk the Jurva pan dry.

However, they were still in known territory. Their guide, Franz, an African hunter, would tell his tales of adventure around the evening camp fires. The end of the road was Panda Matenga, a trading station, where George Westbeech held sway. Next door were two Jesuit priests, Fathers Kroot and Bohn, who conducted a teaching mission. They were welcomed and treated to food and yet more tales of adventure.

The Victoria Falls were only 58 miles away, so leaving their cart and oxen behind, they set off to see the mighty falls. Hammar, like Thomas Baines, before him recorded the awe-inspiring site in an oil painting. Schulz recorded the “glorious view” in lyrical terms.

Hammar's painting of Victoria Falls (Talana Museum)

Back at Panda Matengu, Westbeech had found them 90 bearers and a Dutch hunter, Jan Veyers, to carry their gear and guide them and their three donkeys loaded with canvas bags. Once again they followed a path that had been trodden by two Swiss missionaries, Arnot and Colliard. But the territory ahead towards the Chobe river was notorious for the activities of Mantamjana and the murderous rivalry between the Matabele and Barste. As they moved off into the unknown all they had, was a very old and very inaccurate Portuguese map.

Not long into the journey, Rudolph, the cook, died of fever and they had already come across a number of incidents. And they had ready come across some incidents of treachery among the bearers. July and August 1884 saw the two men coping with the desertion of Jan Veyers, shouldering heavy packs, shambling through hot soft sand, coping with cramping feet, but they carried on. Schulz’s writings and Hammar’s sketches recorded all the details of their odyssey – the splendour of the Mopani and maroela forests, the shrewd features of the “wily old trader Sakoomina”, the cockaded dignity of Chief Moreni, the beautifully ornamented pottery and the eclectic weapons of the tribes.

Eventually they crossed from Linyate, via Jakula’s drift, the Loengure river and the Lina until they came in sight of the Chobe. Great hunting followed and a sense of peace, that they were beyond the reach of the Matabele.

At the end of August, the expedition began the 17 day trudge across the Chobe/Okavango watershed. This became a nightmare. Desperate thirst, failure of supplies and they were forced to eat their sandals – but they survived. As the great expanse of channels and islands filled their vision, they drank their fill and cooked a handsome meal.

Exhausted, frail and feeble they had reached their goal. As they drank in the sights they realised “that they were the first whites who ever gazed on this glorious stream.”

Chief Indala was a threat to their survival. Ever since his run in with the Dorsland Trekkers, he had a great distrust of white men. At Morenie, his men stripped the small band of their supplies and clothing. A Dutch hunter was killed and Schulz’s Zulu bearer, Paul, put on trial for his life. Hammar had to shoot their way out. In desperation, they turned back, seeking sanctuary at the distant trading station, of Mr Stremboom at Lake Ngami.

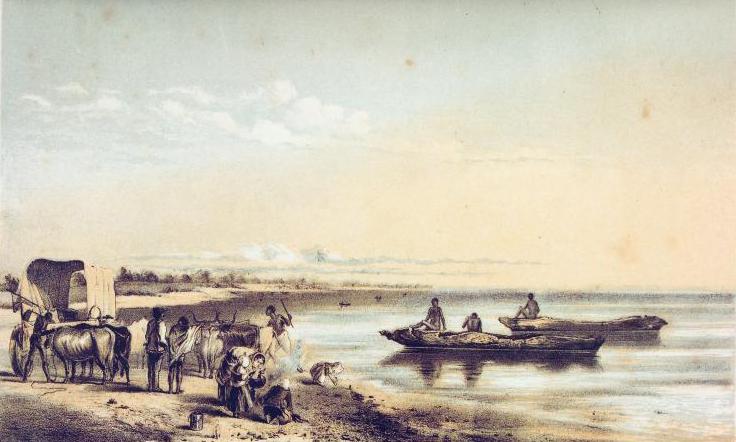

Old painting of Lake Ngami 1857 (Wikipedia)

This was not the end of their troubles, the Zulu, Paul was attacked by a hysterical crowd of women who left him covered with a number of wounds from their blunt knives. Hammar, who had been wounded in the foot during the Indala attack, struggled on in agony “with the welfare of the expedition at heart”. The local Barotse, mistook Paul to be one of Lobengula’s men (possibly because of his language) and again his life was threatened.

Lake Ngami was a sanctuary. Chief Moreni was a gracious host, the hunting was good – lion, elephant, giraffe, leopard and all the smaller game were recorded. October came and went. But the long trek back through King Khama’s territory awaited. This saw tremendous hardships, with Schulz and Hammar reduced to eating ants for survival. The two wheeled cart, lent to them by a trader Mr Steele, could only move at 2 miles an hour through the sand. All December they trudged on via the Thlakane water pits, Haakedoon valley (the name says it all), Lichachana and the Malatzwye water holes until they reached the junction of the Zambezi and Lake Ngami tracks. They were on the high road to home.

To celebrate Schulz “had a shave – the first in 9½ months”. A storm cooled and hardened the blistering sand and they were able to walk on ‘the first solid ground for months”. However, they were almost at the end of their endurance – only a handful of corn remained to feed them.

Their arrival at Shoshong was triumphant. Schulz and Hammar marched in clean “clothed in our best shirtsleeves and much worn frayed moleskin” and their last pair of boots. The traders were amazed as they had all speared rumours of their deaths. After an idle week at the hot sulphur springs in the Waterberg and some hunting they headed back to Dundee.

Seven Sisters Waterberg (Richard Wadley)

Visitors to Dundee in later years, would not have recognised the successful doctor, geologist and coal entrepreneur Dr Aurel Shultz and the distinguished Surveyor-general of Natal, Mr August Hammar for the intrepid explorers of 1884.

With the publication of the book, and an interview which was published in The New York Times on 18 December 1897, as to why they had delayed so long before writing their account, Dr Schulz answered “that since we were the first whites to traverse partly unknown country, no explorer has followed in our footsteps, and the regions of the Central Chobe and the country we traversed from here to the Okovango still remain partly undescribed territory….this country has been difficult to access to the ordinary sportsman.”

He then continued to add during the interview that “I am one of the few individuals to have seen both the Victoria and Niagra Falls, perhaps it will occur to the reader as it did to many Americans whom I met, which is the greater Fall?....unhestatingly stated that the Victoria Falls burst on one’s sensebility with appalling grandeur, while the Niagra at first appear to be not so marvellous, but by growing on one seem to increase in magnificence the longer one stays by them.”

Pam McFadden has spent many years researching the battlefields of KwaZulu-Natal. She has been interested in them since a young child. As a registered specialist guide on these battlefields for the past 40 years her knowledge about events and the people involved is considerable. Since 1983 as curator, Pam McFadden has developed the Talana Museum in Dundee into one of the finest in the country. As part of the museum collections she has collected and created an extensive museum archive, that holds many treasures.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.