Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

It is said that the Portuguese Empire came to a fall partially because of all the cargo-filled shipwrecks that line the South African shores. A hundred years before Jan van Riebeeck landed at the Cape, the survivors of the first of these shipwrecks were left with no choice but to walk to the nearest watering port in Mozambique. This event led to the earliest documented prolonged stay of Europeans in Southern Africa. Many shipwrecks after that left hundreds of people stranded on our coast during the Age of Discovery. Some of these survivors decided to stay and were integrated by the local communities, while others made for Mozambique or the Cape. Many died along the way. Their degraded bones are now a part of our land, of us.

Despite the fact that these early shipwrecks left a great impact on South African genetics, culture and language, as well as popular European opinion of Africa and Africans at the time, they are merely glossed over in our history books. No fewer than nine of these ancient wreck sites can be traced between Port Elizabeth (Gqeberha) and Port Shepstone, most within range of a day trip from holiday destinations along the coast. The stranded passengers on every ship made different decisions from their predecessors, which led to different outcomes. Their heart-rending stories are about a forgotten age, courage in the face of adversity and tribulation, and the indomitable human spirit.

Shipwreck sites dating from 1552 - 1713

The first of these shipwreck sites mentioned in original detailed narratives from survivors can be found at Sardinia Bay Beach near Gqeberha. It was during the Santíssimo Sacramento's maiden voyage that she was caught up in the same storm as her consort, the Atalaia. Running before high waves, the Sacramento struck land and quickly went to pieces. After travelling for a month, the 72 survivors came across the Atalaia wreck. They set a quicker pace to catch up with the other survivors. By the time they reached the wreckage of another shipwreck, the Belem, they were so famished that some devoured a shoe they found as well as the mariner's chart. The last nine survivors eventually met up with the Atalaia party.

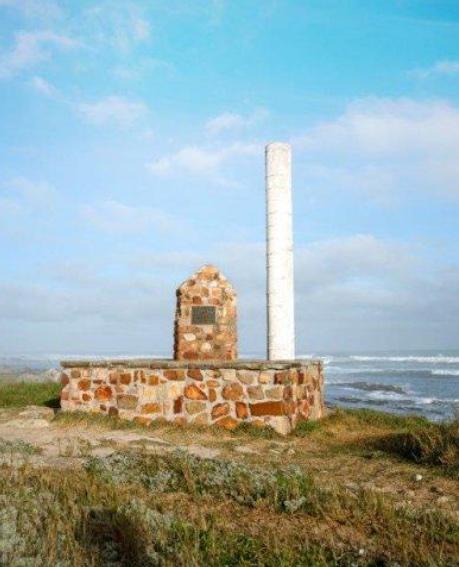

The Sacramento monument along the Sacramento round trip coastal walk through the Schoenmakerskop-Sardinia Bay Nature Reserve (Nelson Mandela Bay Tourism)

If you travel 147 km on the N2, you will reach the São João Baptista wreck site at Cannon Rocks. It sailed from Goa in 1622, but was caught in a running fight between two Dutch ships sailing in the opposite direction. The fight lasted nine days, during which the ship's rudder, bowsprit and main mast were lost. Thankfully, a storm blew in, separating one of the Dutch ships from the engagement. While the Portuguese were driven landward by the wind, they lost the remaining enemy ship. In seven fathoms, they cast anchor and, using a line, 279 people waded ashore close to where Port Alfred is today. They set off for Mozambique using the cows they had bartered for as pack animals.

The São João Baptista wreck site was identified by Graham Bell-Cross as Cannon Rocks, though the anchor dates from a later shipwreck (We Travel)

116 km up the coast south of Hamburg, a Dutch East Indiaman wrecked at the mouth of the Mtana River and was smashed by the rough waves in 1713. The 77 survivors of the Bennebroeck decided to walk to the Cape, but, faced by an impassable river, most turned back to the campsite. Of those who decided to continue, only one slave made it to the Cape more than a year after the wrecking. Four months later, the others tried to reach the Cape again, but were once more defeated by the Fish River. An English trading vessel found the remaining nineteen survivors supported by the friendly Xhosa in 1714. Four survivors went back to Cape Town while the rest preferred to integrate with the local community.

Travelling northwest from Hamburg for 114 km, you will find Sunrise-On-Sea. This is where the Santo Alberto ran aground in 1593 after it left Cochin. As soon as the leaking galleon came within sight of Natal, goods were thrown overboard to try and raise the stern. The ship grounded 400 paces from shore, with the upper decks parting from the lower and drifting close enough for the 285 people on board to land dry-shod. The Santo Alberto party chose a route further inland, negotiating with friendly locals to guide them more than 1,100 km to the watering port in Maputo Bay.

The Santo Alberto wreck site was identified in 1979 by Graham Bell-Cross from washed-up Ming Dynasty porcelain as the beach of Sunrise-On-Sea.

23 km away, between Cefani and Chintsa, is the unmarked Atalaia wreck site. It sailed together with the Sacramento from Goa in 1647. To celebrate Easter Day, the Nossa Senhora da Atalaia do Pinheiro fired seven shots to salute its consort, but the reverberations opened the seams, and the ship began to leak. The main mast was lost in a gale amid thunder, lightning and hailstones the size of hazelnuts. At the mouth of a river in a bay, the ship's rudder struck land. During the sixth boat trip to shore, it capsized and was smashed. The band of survivors met nine people from the flagship Sacramento, which had foundered in the same storm, and they continued on their journey together. Six months later, they reached Maputo Bay.

The next wreck site is a stretch of 299 km away since the N2 does not hug the coast between Chintsa and Port St. Johns. In 1635, the Nossa Senhora de Belem sailed from Goa. Within days, slaves manned the leaking carrack's pumps on the short-staffed ship. They found the worst leak in the stern, which gaped like "lattice work," but the carpenter had fallen overboard in a faint after he was bled many times and nobody else could fix it. The ship ran aground at the mouth of a river in wild surf. Deciding not to trek through the wilderness, it took the party of the N. S. de Belem six months to build rescue boats. One of the boats was lost, but the other made it all the way to Angola.

The São Bento ran aground against Msikaba Island 79 km further. Manuel de Castro, one of the survivors of the São João which wrecked two years earlier, died the next night from a serious leg injury. The survivors salvaged washed-up carpets, silk and gold cloth to construct a luxurious campsite. A few days later, they set out to follow the same perilous journey of the São João survivors. They met a few along the way who were then encouraged to finish the journey. Of the 322 survivors, 25 were rescued.

Cannon salvaged off Msikaba Island mounted to overlook the São Bento wreck site.

The oldest story is that of the São João, which left Cochin, India, on February 3rd, 1552, bound for Portugal. The hull was filled with about 340 tonnes of pepper as well as Ming porcelain. Before it reached the Cape, the ship hit storm after storm, causing so much damage that the officers decided to head for land. Among the 500 people who survived the shipwreck were the Captain's young, aristocratic wife and their two infant sons. After five and a half months of enduring starvation, disease and native attack in the wilderness, only 25 people were rescued.

The second Dutch ship wrecked 36 km away in 1686 where Port Shepstone is today. Pilot error was the reason the Stavenisse ran aground. 47 survivors decided to walk to the Cape while the remaining thirteen were joined by castaways from the Good Hope (1685) as well as the Bonaventura (1686). Together, they built a rescue boat, the Centaurus. Upon their arrival at the Cape, Governor Simon van der Stel had their boat refitted with the instruction that they should return to find more survivors. They found twenty-one survivors, including the fifteen-year-old 'French boy', Guillaume Chenu de Chalezac, whose own narrative is filled with more adventure than most of us will see in a lifetime.

Those who drowned along our coast or died through hardship in our wilderness during our country's early history are an important part of our heritage. The pieces of themselves the Portuguese and Dutch lost along our (then) lonely shores can today be traced in the faces of our local peoples and can be heard in folklore and legends of clans who have lived on the coast for centuries. Unfortunately, most of these sites that have seen major loss of life are unmarked. Only four of them have monuments. We should treat these as places of gathering, of sharing information, of remembrance and we should celebrate the people long gone who contributed to making us the nation we are today.

Main image: The lovely monument in Port Edward which commemorates the sinking of the São João. (SJ de Klerk)

Jukie Joubert is finalising the last touches to a historical fiction manuscript that has been ten years in the making. During that time, she has gathered information from archived material in search of original survivor accounts, and she referred to literary sources of the time. She has spent time walking lonely beaches to retrace the journeys of shipwrecked survivors, noting the monumental architecture of medieval ports, churches, and mosques.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.