Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

The article below forms part of Mike Alfred's series on Joburg personalities from the first decade of the 21st century. Click here to view Kathy Munro's fantastic introduction and here to view the series index. The stories were written in 2005/6.

It took some hunting to find Kenneth Stanley Birch or KSB as he is sometimes called. With no telephone entry I began to feel like a private eye. I had incorrectly assumed him dead, because the dates on the prints of his memory provoking watercolours of Witwatersrand gold mines went back many years. My wife had found some of those prints buried in a charity shop. Knowing they would interest me, she bought some. They were more than interesting, providing as they did, a pictorial reminiscence of our economic heritage; the basic, golden reason for our existence in this great, forested metropolis on the highveld. I then made a few fruitless enquiries about the artist. Months later, Geoffrey Klass, of the Collectors Treasury (click here to read the essay on the Klass brothers), told me that he’d spoken to Ken Birch who sounded very much alive. But Klass could supply no contact details. After several other queries, someone confirmed that Birch had once been Group Architect for Anglo American Corp. So my quest moved to that company’s administration. Quite by accident, because Birch had taken a lump sum pension and was no longer on the books, a helpful woman ‘found’ the 90 year old. When contacted, he agreed to be interviewed. I arrived on the wrong day but he was happy to talk. ‘You’ll excuse me for not having shaved,’ he said, ‘I’ve been shaving for 77 years so I thought I’d give my face a rest.’ If the man had proved elusive in the finding, he was at first, even more so when we sat face to face.

He appeared to accept me quickly, bade me sit and proceeded to talk, and talk, and talk, tapping his voluminous and labyrinthine memory. I soon learnt that he operates his own internal free association process. His recollections are complex; digressions are numerous. As he describes his mental journeys, ‘I occasionally venture down a branch line.’ Occasionally he seems to remove himself; he smiles sweetly as he replays and becomes immersed in an intense filmic memory. He assumes satirical or exaggerated accents when he describes certain personalities or interactions. It seems that he remembers half the world’s people. Mischievous and wayward, he doesn’t respond easily to leading questions. I’m left with little doubt that he’s been independent, autocratic and strongly opinionated all his life. He’s watchful, notices people’s foibles, a trait which does not necessarily induce popularity. He’s been called conceited more than once. He’s ‘never been a pushover.’ In mature old age he maintains that he’s ‘still contending.’

Kenneth Birch (University of Pretoria)

So this is a series of glimpses into the life of a man who was born into a comfortable and privileged English South African family just before the start of the 1914-18 War. His parents had arrived in 1892 to establish a new life for themselves. It is the story of a man educated at Jeppe preparatory and high Schools and later, in the 1930s, in the faculty of Architecture at Wits. It’s about a scholar and sometime soldier who fought ‘up North’ and in Italy during the 1939-45 War. He chooses to describe the two major Twentieth Century conflicts as European Civil Wars, those emanating from Continental rivalries; a perspective which tells us much about his world view. Birch is broadly talented, not only an architect and town planner but a musician and an artist skilled in the use of watercolours. Wherever he went, and he traveled widely in Africa, Europe and the Middle East, he sketched scenes ‘before they disappeared into the swamp of the modern traffic jam.’ He never painted from a photograph. His camera was used only to record architectural projects and people.

He worked for the Anglo American Corporation as Group Architect for 22 years and after retiring from that company, he at first occupied himself with preserving South Africa’s heritage. He was able to do this as a result of his historical expertise and his financial security. By far the most important of his post-1970 occupations has involved his attention to humanitarian efforts. During his retirement years he has been able to channel funds into philanthropic projects. Among other bequests, the department of Family Medicine at Wits owes its establishment to Birch. He’s a creative intellectual, whose papers, sheet music, photographs and various book and art collections enrich the archives of several South African museums and universities. Many individuals and institutions acknowledge his unusual generosity, but he moves quietly, he’d hate being known as a sanctimonious do-gooder.

His factual, scholarly research into the rise and fall of ancient cultures and civilisations has convinced him that the 1700 year old European civilisation is crumbling. He despairs the poor example it offers Africa. He feels compassion for the contemporary world and its mindless pursuit of wealth. He wonders whether ‘this euphoria of everlasting growth, consumerism, the billionaire complex, is likely to create paradise?’ All living matter he believes, follows the inexorable Laws of Creation, of birth, youth, maturity, decline and death. He calls himself a prophet, someone swimming against the tide; sees the rejection of courtesy and the loss of tradition all around. Uncertain about perpetual boom times, he reiterates an ancient Roman edict, “All men when prosperity rages, should know how to face adversity.”’

He lives in the Jacaranda shaded old Johannesburg suburb of Melrose. His property, house and indigenous garden are traditional. His house, in which he lives and works, offers a portrait of experience and discernment, the intimate environment of a man who confesses to having enjoyed ‘a tempestuous but rewarding life.’

For his age, Kenneth Birch is amazingly vital. Using a wheeled walker he outpaces me. His intensity of gaze makes one immediately realize that this is a man not to be crossed. His body is slim. His voice is strong and resonant; he commands his retainers with old fashioned assurance and respect. He regards them as his family. Their children call him grandpa. His appetite is hearty, and the occasional champagne indulgence is just the thing to spice a life which still presents him with challenges and which he finds naturally invigorating.

But, this is a man whose rich experiences encompass four fifths of Johannesburg’s history, whose life provides a particular window onto much of the Twentieth century. This is a man to whom I am delighted to listen; someone whose longevity offers me a theatre of unusual material. His memories of early Johannesburg and its people are rich and extensive. So rich, that alas, within the constraints of this essay I can do them only partial justice. Where might one find a man alive today who remembers attending his first Xmas pantomime “Babes in the Wood,” at the old His Majesty’s in 1919; who visited Florrie Phillips at Vergelegen; who knew Hermann Kallenbach [Gandhi’s architect disciple] well; who watched Whiskers Blake wrestle and Willie Smith box in the thirties; who corresponded with Agatha Christie; who sat in tea room bioscopes; who heard and saw famous early 20th century stage and opera stars; who talks with such familiarity about Herbert Baker and his architectural protégés, J M Solomon and Gordon Leith. Birch later worked for Leith and was with him at his end. Birch remembers inspecting with his family, the artillery damage to Fordsburg Square immediately after the 1922, Rand Rebellion. An episode incidentally, which he calls the Red Revolt, a name fashionable at a time when the capitalist world was terrified of communism and white Labour was terrified of being replaced by black.

Market Square Fordsburg during the Rand Revolt

Birch’s parents, Walter Birch and Alice Besant came from Hampshire and Dorset families which were prosperous in the 18th Century but adjusted poorly to the Industrial Revolution. In 1888, aged 20, Walter sailed for South Africa. Having established himself, he returned to marry Alice. In January 1892 he brought her to South Africa. They arrived in Johannesburg in 1895 as the Jameson Raid was taking place. Between 1892 and 1902 they not only established a family of four girls and two boys but, unusually for that day and age, assumed equal responsibility for developing a successful building and decorating business serving the burgeoning town. Birch describes them as, ‘partners in all aspects of life.’

KSB, did not appear until May 1914, twelve years after his closest sibling, a sister. His father and mother were then 47 and 43 years respectively. He grew up among adults but although ‘late on the scene,’ he placed himself in the same generation as his brothers and sisters. This explains why he is ‘ancient and modern in behaviour, why I am both a mixer and a loner.’

He was the first family child to be born in a maternity facility, Nurse Macmillan’s, which now houses the Bertha Solomon Centre and Clinic in Jeppestown. He was taken home to the family residence in Kensington. Rocky Langermann Kop provided his outdoor playground. As a child of strong willed, middle aged parents, he was reputedly also difficult from the start. He remembers rattling his steel cot to demand attention. And he remembers his mother later threatening to place him with the orphans in Nazareth House, Yeoville if he didn’t behave.

Recent view of Joburg from Langermann Kop (The Heritage Portal)

His parents were active and outspoken. They held Cecil Rhodes in low esteem and father played no part in the Anglo Boer War. Birch wonders how he got away with it? In 1905 they voted for responsible Transvaal government. In 1912, father visited Europe, England and the USA. He just missed traveling on the overbooked Titanic. Walter Birch died suddenly in 1917 during Ken’s fourth year, a great loss. His reserved brothers, then 19 and 16, paid little attention to him. They never taught him ‘to keep his eye on the ball,’ nor allowed him to ride their bicycles. He was very fond of his 22 and 18 year older sisters upon whom, in the early days, he relied more than his mother.

He grew up in an early Johannesburg suburban home reflecting Victorian values and presenting a varied panorama embracing Anglican Christianity, chickens and ducks in pens in the garden, responsibility for household chores, musical evenings, jazz on the phonograph, evening treats to the bioscope and theatre, picnics, boyfriends and dances for the younger sisters. He was constantly exhorted to keep his nose to the grindstone. Up to the age of 11 he was sent early to bed, but in the nature of smart children, he always fell asleep with an appreciation of ‘what was going on.’ He spent his annual school holidays at the coast or on farms. He remembers driving around South Africa with the family, seeing the krantzes white with vulture droppings, the great swarms of locusts devouring every thing in their path. He remembers watching the swallows gathering for their annual migration north. Of the family interactions he recalls, ‘We were not a docile family, not lovey dovey, nor ‘smoochie’ but we enjoyed many arguments and much laughter.’

Birch remembers the family doctor, Taylor Brown, who, white coated, ‘with a moustache like Poirot,’ drove up in his open tourer. ‘There was a bottle of sulphur and treacle on the pantry shelf; when the Dr said, “Give him a spoonful of that,” I was cured in next to no time. He exerted a powerful influence upon me, intimating that malingering was not acceptable. He also told me about my father.’

KSB started prep school in January 1921. He recalls, ‘In June, despite protests, the matriarch takes me off to Europe for seven months. Of course that trip comprised some of the best education I ever received: the ship, the trains, the sightseeing, the underground, Crystal Palace, my English relations. I came back to school full of ideas, much too bumptious, no one else had enjoyed such an opportunity. In 1924, the Afrikaans teacher, Miss Louw, decides to take the mickey out of this little, sissy jingo. She shouted and raved, went purple, “Groot praat, jy is mos a Bessie.” Thereafter some boys set upon me and I ran away. I could not squeal to anybody, so I had to make up my mind. Do I stay and face the music or run? By the time I got to high school I could stand on my own feet. In all my student years the only teacher I ever jerked was Miss Louw. Poor thing, she had a nervous breakdown later that year.

‘I had some first class teachers at both Jeppe schools. At high school the outstanding St J B Nitch, taught me history. I received top marks in that subject every year.’ Birch was asked to play Macbeth in the school play. He turned down the offer. ‘Ever after I regretted the chance to rant and rave in public. I’ve chickened out of some situations during my life, due to weaknesses and irresponsibility. Some remain in my memory and annoy me to this day.’ Scholarly Birch claims no ‘gladiatorial instincts’ at school. Nor was he a natural team player. Sport for him was a matter of exercise and recreation, rather than the ‘skop hom dood’ philosophy. He disliked soccer and cadets but his skill with a rifle won him the Bisley.

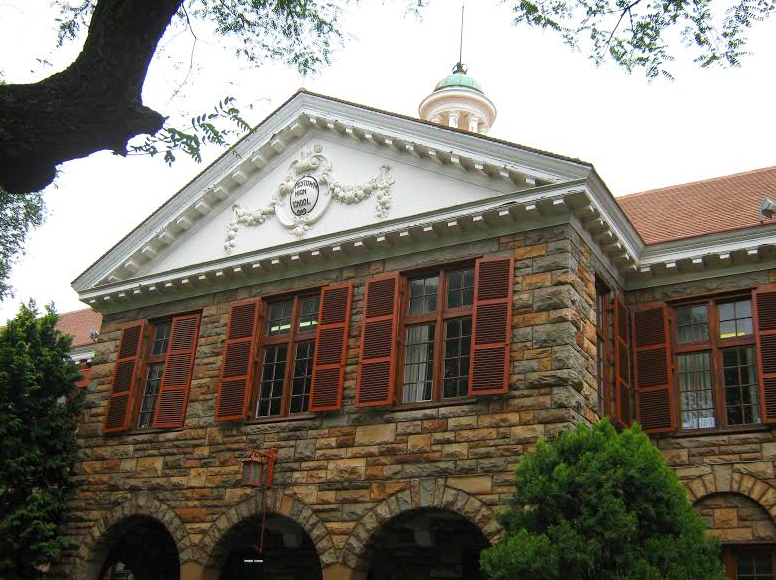

Jeppe High School (Kensington Heritage)

After 1928 when all his siblings had left home, KSB was alone with mother at the spacious Kensington house. ’Momma wanted her own way, Kenny wanted his own way and I sometimes paid no attention to momma’s instructions. Not overindulged in the facts of life, I was conducting my own adolescent experiments. There was a certain diffidence in the Victorian family; sex was de rigeur and I never heard my elder siblings exchanging ideas.’ Reflecting on later experience, Birch says, pre occupation with and occupation with sex are two very different things.’ Experience has taught him that the act without affection is overrated. He expresses compassion for the modern generation who seem robbed of innocence too early in life. He says, ‘In 2005, sex is nothing but a top market, shiny magazine!’

‘Alone with mother, I was the man in the house, so I gained a subtle sense of responsibility. When I was sixteen in 1930, mother gave me this birthday advice:

There is only one thing in life worth living and that is to run straight. Don’t for God’s sake, ever play a double game, or give people away who trust you. The truth, the whole truth and nothing but the truth.

It was a good principle, important enough to be cherished all his life. His descriptions of his mother suggest her strong influence. Birch recalls, ‘When I was about 22 at a party in the French Club, I was told by an Oxford don that I had a mother who, in her infinite variety, resembled Shakespeare’s Cleopatra. I have always appreciated this unsolicited compliment. A widow for 47 years, my mother faced several very difficult situations in life. I never saw her floored and only once in 50 years did I see a tear shed for her son Arthur, while he was in hospital recovering from serious surgery. After my father’s death she ran the family estates and exercised final control until her death in 1964 in her 93rd year.’

One of those tough situations involved Birch’s second sister, born in 1894, nicknamed Toby, who gave birth to his niece, the talented, coloured writer, Bessie Head. In an attempt to deal with the ‘fancy legends’ concerning Bessie Head’s early life, Birch has written a monograph entitled: The Birch family: An introduction to the white antecedents of the late Bessie Amelia Head. This was published by the University of the Witwatersrand Press in 1997. Today he regrets that he did not do more to find his niece and form a significant relationship with her.

He relates, ‘To a so called, respectable family, the cross colour bar, 1937, bombshell birth, gave rise to great drama. This continues to this day, years after Bessie Head’s death. When Bessie Emery [as she then was] left high school in Natal about 1955, the matriarch placed the final taboo on illegitimacy. She said, “Out! This girl must make her own way in life.” This autocratic injunction suited most of my family only too well. By 1970 the main Birch family were aging or gaga but sister Dorothy and I have feelings of guilt. I started to look for my neice, but what if she’d become a shebeen queen? I tried not too hard. How was I to know that this girl was brimful of the energetic Birch, Besant genes, writing her terrifying novel on the conflict between good and evil? My intelligence and energy look shabby at this point of no possible return. I fall within the timeless indictment of the Prophet Job, “If I justify myself, my own mouth shall condemn me.”

Once at a party in his home, at which Alice Birch aged 90, was present, she was asked by a guest. ‘Are you related to Annie Besant?’ [divorced suffragette, feminist and founding Theosophist.] ‘In reply Alice Birch answered, “Yes we’re related but I don’t know what that woman’s about. She wants to change the universe. A woman’s duty in life is to find a decent man and make something of him.” Mother, like son, was adept at ‘taking the mickey.

KSB relishes this story. ‘In 1937 I bought a lovely Ariel 500cc motorbike. Expecting trouble I wrote a note with my left hand purporting to come from the secretary for the committee, saying that I had won the tennis club raffle and that they had pleasure in presenting me with the prize. Momma said, ”This looks surprisingly like your handwriting.” But in this case, right or left, I won the day. Momma could read the riot act, but once she paid me the compliment, “You’re the only one of my seven children who ever listens to anything you are told.”

In 1936, Birch qualified in architecture at Wits. He made the most of the ‘universitas.’ During his student years, in addition to his formal studies, a stimulating world of art, music, literature, the humanities and recreation opened up to him. He won several academic prizes. During his first two vacation assignments, he worked as an artisan on building sites. He helped plaster the Colosseum cinema. In 1936, he spent seven months on a life and architectural study tour in Europe. He recalls, ‘I met Le Corbusier in Paris. I went to his place for lunch. He couldn’t much speak English and I then couldn’t speak much French, but we got on very well together. He made a drawing for me. We met for the last time in Marseilles in 1952’.

Colosseum Theatre in the 1930s

At Wits he became yet another student to revere the modern functional movement [“the house is a machine for living”] promoted by senior lecturer Rex Martienssen, later to become the renowned Professor. Another of KSB’s teachers was Englishman, Stanley Furner, recognized as bringing modernism to SA and who later joined the Kallenbach and Kennedy practice where he designed the Plaza cinema in Rissik St. Birch joined Furner and others on Monday nights at Monica McIver’s studio to discuss ‘the high flying arts.’ He was also invited to join a group of literary intellectuals which turned out to be a communist cell, mentored by the later-to-become-notorious and later still, heroic, Bram Fischer. This group of comrades together with university counterparts all over the world, espoused the cause of radical socialism, seeing it as an answer, particularly during the Great Depression, to the then so visible consequences of unbridled capitalism. At this point Birch raves, ‘Capitalism in 2005? There’s no such thing! Now it’s unprecedented greed.’ Also at that time and not unsurprisingly, he questioned his religious roots and moved towards atheism.

Rex Martienssen (Wits University)

In 1937, in the final round for the Elsie Ballot, he lost the scholarship to Cambridge because, so he believes, he told the examiners in answer to one of their questions, that consideration of the forthcoming European war was more important than cricket test scores. This vignette, so the writer believes, illustrates Birch’s personality well.

Birch recalls the Johannesburg of the thirties: ‘By 1930 Johannesburg was no more the mining camp known by my family. It had become a city. When the gold boom started in 1934, Joburg became a miniature New York, where ‘moths’ were attracted to the bright lights of a rebuilt city centre; where they “heard the beat of dancing feet in Prichard [42nd] St.” Birch notes that the period between 1918 and 1939, the years of the war torn generation, were the red sun days of the Global European civilization. ‘By 1950, it was all over. Those times will never return. Today we are leveled out, where are the peaks to which we can aspire?’

Between 1937 and 1940, Birch worked for the then famous South African architect, Gordon Leith, one of Herbert Baker’s protégés. Leith, among other noteworthy projects, designed the Johannesburg Railway Station where the atrium housed the famous Blue Room restaurant and featured the Pierneef murals now removed to the Johannesburg Art gallery. Leith was also responsible for designing the Pretoria and Johannesburg Reserve Bank buildings and the edifice that housed the Rand Water Board. ‘Leith was a very capable virtuoso,’ says Birch, who remembers altering one of the boss’s drawings, whereupon Leith tore them up and stamped on the remains. During his time with Leith’s studio, Birch worked on the Union Corporation building at 74 Marshall St, by day and savoured Johannesburg’s social amenities in his free time.

Old photo of the Blue Room

Old Reserve Bank Building (The Heritage Portal)

Union Corporation Building

His crowd danced at the French and German Clubs, dined at the Luthjes Langham and Carlton Hotels, saw movies from Hollywood’s ‘Golden Age’ at the Metro and Colosseum cinemas, played tennis together, flew planes at Baragwanath and Rand airports, spent weekends camping at Retief’s Kloof in the Magaliesburg and at Loskop Dam, ‘where a boere dans was thrown in.’ They were entertained in private homes under watchful parental eyes. They hired riding horses from Bob Grayston’s stables and, regarding those animals, Birch always thought they knew more than he did.

Old photo of the Carlton Hotel

During the late thirties, Birch enjoyed one of Johannesburg’s glorious times. He loves ‘old Johannesburg,’ the centre city of great mining houses, the milieu in which he grew up. He makes mention of ‘the old suburbs.’ He describes the Witwatersrand in astronomical terms with Johannesburg as the sun, Pretoria the moon and the reef towns and their mines as the planets. He wishes Sandton had remained ‘mink and manure country.’ He mentions the Jewish community, so influential in those days, stating that Johannesburg would never have been what it was, ‘without those attractive, “chosen people,” so quick off the mark. There are so few of them left, so few with whom I can enjoy a good laugh.’ He maintains that Johannesburg in the period 1937 to ‘39, ‘was for him, better than being at Cambridge. The city was intimate then. You’d go to a concert and you’d know half the people there.’

Sandton Skyline (The Heritage Portal)

After the Nazis began to overrun Europe in 1940, Birch joined the South African army. ‘In 1937, we boys already knew, the second European Civil War was coming. We knew we must go and we expected 1914-18 conditions.’ He served first as a despatch rider in the Tank Corps, but soon, his qualifications took him, as an NCO, into the SA Engineering Corps. He trained at Premier Mine depot and was later promoted to 2nd Lt, and transferred to 85th Company, Deception and Camouflage. He landed in Egypt in June 1941. In November, his squad was detailed to First British Armoured Division for service in the desert. Birch recounts, ‘action was varied; sometimes rough stuff, sometimes not much to do, and we always wondered, what was going to happen next? In 1941, The Luftwaffe was still strong. When in June 1942, I returned to the Delta on leave, I was sorry to go. My open air activities in SA had schooled me to enjoy desert life. I spent nights stretched on the ground watching the stars before falling asleep; sometimes wondering whether that moving salt bush concealed a Jerry sniper? Later, in Italy during the 1944 battle of Sangro river, I was riding my motorbike along a white limestone track. A voice came from the darkness,”Gut efening meester engelsman.” I retreated as gracefully as I could.’

‘I saw the Germans defeated only 35 miles from Alexandria. Between 1940 and 42, the desert war swung on the pendulum of logistics. Now, in November 1942, after the battle of El Alamein, General Smuts issued a decree saying that South Africans who’d served outside the country for two years could return home. I wanted to follow Rommel right through to Tripoli. But the South Africans lost the job to the New Zealanders. Back at base camp I say to the OC, a man of 1914-18 vintage, “I don’t want to go back to South Africa. I joined the war to finish it.” My idea was I’d be demobbed in Britain. Because from my pre war experience, I wanted to live in the civilized part of the world and not back with a lot of beef eating, paunchy, rugby forwards. Right, and ah, culture; art, music, theatre, sophistication, everything. Build a brave new world, rebuild the slums of Europe. So I said, “I’m sitting here and the British are running an intelligence course in the Helwan base, can I go?” So I go to that for two weeks. As it’s drawing near the end the OC says to me, “Would you like to go to the Staff College in Palestine? It’s a three months stint.” I think, Staff College, what’s that?

‘So I rush round to the Pommy unit next to us and say, ‘What’s the Staff College?’ They say “Ooh I say, right, Staff College, this is sending you up a military rung. We’ll change with you any time!” Back I went to the OC, I told him, “I’m only too keen to go this Staff College.” I’ve been ever grateful for this opportunity provided by my OC, Major Wilfred von Berg, a Johannesburg architect. So in February 1943, off I went and of course I had the spring in Palestine, enjoying the biblical beauty. For three months I learnt a great deal about intelligence work, strategy and administration. Not always attending the weekend parties and binges, I also went to Jerusalem, where I visited famous historic sites and met local personalities, one of whom was Flinders Petrie’s [famous archaeologist] wife, Hilda.’

In Egypt, while at base, Birch made the most of Cairo and Alexandria, those intensely stimulating world cities, ‘so much more venerable than Johannesburg.’ Birch visited the ancient sites, explored the wartime-reduced museums, made friends with important Egyptians, and gathered the nucleus of his Civilisations book collection now residing in the library archives at Unisa. A life member of the Egyptologist Society, London, he speaks with as much ease about Egypt’s ancient rulers as he talks about his own friends and acquaintances. He laughs, wondering whether he sounds like a war time tourist rather than a soldier? but explains it as an ability to do more than one thing at once. He enjoyed the soldierly leave life in the army clubs where the colonials met. There the routine was ‘booze, laughter, exchanging vows of eternal friendship or occasional blows, followed of course, by the morning after hangover.’ We traveled the streets in horse drawn gharries and visited Mary’s and other notorious houses on the Sharia, el Gizeh. During the war Cairo’s street lamps were painted blue, giving the city an unearthly, glamorous night time radiance. It was called the “blue out.”’

When Captain Birch returned to Cairo having completed the Staff Course, he found that his South African unit had returned home. He volunteered to join the British army. ‘The British couldn’t find enough officers to staff their conscript army, so they had to ask us colonials. I said, “I’m only too willing to serve the greatest culture within the European civilization.” At least, I thought so then. I was put into a Beach Landing Group for the invasion of Sicily.

‘We had no problem landing on Sicily. There was a vineyard at hand. We, the 8th Army, were unopposed. We were going to have this great tank battle, and then we’d sweep through like a dose of salts. But the Germans were waiting inland on the Plains of Catania. British intelligence seemed to think these flats would be like the desert. The plains were a morass, ditches filled with winter rain off Mt Etna. A tank bogged down is a sitting duck. The Germans gave the British a hard time, tore the armoured division to pieces. It was the Americans who won Sicily. Sicily was my introduction to the Yanks. I saw modern mechanized power for the first time. The ‘Empire’ was still in the pick and shovel age. The war was won by Yank technology and Russian manpower.’

After Sicily, in mid 1943, Birch was sent back to North Africa to join the Italy, Salerno beach group. ‘I caught a beach landing craft, sailing to Bizerta. Three LSTs set off from Port Augusta through a German air raid; we got through that all right, and we got to Malta where we spent a day and then set off on the night of a full moon August 24th. The sea was dead calm. These ships were designed so that soldiers were accommodated on the sides, and on two middle levels, there was space for tanks and vehicles which landed on the beach across the dropped prow. The ships were empty of soldiers except for me, a British sergeant and a few other ranks going back on compassionate leave to England.

‘We sail along, it’s bright moonlight and we turn in. I slept in the crews’ quarters at the back end. The British sergeant goes and sleeps amidships. At two in the morning all of a sudden there’s the most terrific crash. Bang, clang, wham; it was like one of my later mine stainless steel kitchens crashing to pieces. I get up. We had one destroyer with us and the destroyer’s going around in circles dropping depths charges into the sea. I say to the sailors, “what’s going on?” “Oh, we’ve been hit by a torpedo.” The sea is as flat as a pancake. There is Cape Bon outside Bizerta standing out in the moonlight. “So we’ve been hit by a torpedo, when are we going to sink?” But the hole is two metres above the waterline. I looked out and there was this long ship with a bump in the middle. The sergeant who’d been amidships is killed. Later on we get put on tow, we sail onto the African beach, lower the front and walk off. And we wondered how could a torpedo have jumped out of the calm water?’ Birch later learnt that the LST was hit by an early German flying bomb launched from a plane flying out of sight, many miles distant.

‘That night in a Tunis night club I danced with a French vedette. She sang “Dans mon Jalousie” in a deep, rich voice. I went awol for a few days to look at the ruins of Carthage and reflect on the love of Dido and Aeneas.

‘The Salerno landing was dicey. The Beach Group was attached to the British 7th Armoured Division but we fought alongside the Yanks on the Ebro River. Their Lockheed Lightnings and battleships at sea gave the Germans a pounding.

‘And at the end of Salerno, I saw the war in the Mediterranean wasn’t going to finish, and as a leftie, I was all for promoting the 2nd front to assist Russia, so I said, “now look, I’ve had experience in two landings, I want to be transferred to Britain and I want to go on the force when it lands on the second front in France. I can speak and write French quite well, my Grandfather was a Frenchman and I want to serve these two brilliant allies and these two brilliant European cultures.” I was then still somewhat starry eyed. But the Director of Military Services said, “You can’t do that, because as a South African, you can’t go out of the Mediterranean theatre.”

‘As the war went on, I became pretty bolshie. I was going back to my Wits days. I’d been very religious at the beginning of the war because I wanted to save my skin. I didn’t have a father to ask and my two brothers had missed both wars. So I thought well, I must ask God: “God you save me!” Like the modern happy clappy religions, “God, you do what I want!” As time went by, I was getting out of that salvation syndrome and I was going back to Rationalism, the Wits left wing, brave new world stuff, Liberty, Equality, Fraternity.’

However, December 1943, saw Captain Birch a staff officer in Algiers. ‘There’s a big do at the posh St George’s Hotel. Here is Roosevelt, Churchill, Voroshilov, the Russian Ambassador, all preparing to confer with Stalin at Yalta. The Director of Military Services puts me together with Voroshilov’s ADC because we both talk French and can interpret. Birch is dressed in his mess kit. I saw myself in the many glass mirrors. Boy was I handsome!? I was reminded of that old jazz number which went: You must have been a beautiful baby, ‘cause Trotsky, look at you now. Soon after the ‘party’ the DMS sends me back to Italy where I report to General ‘Ginger’ Hawksworth, OC, 46th British infantry division, called the Oak Tree Division. He was my ideal leader, no spit-and-polish tailor’s dummy, and he wouldn’t allow buck passing. I stayed with the Division from Monte Casino until the end in the Po River valley in April 1945.

‘In the Division I was promoted to Major and reported to Adjutant and Quarter Master, Colonel Gordon McMurtrie, a West Country lawyer in civilian life. “Uncle Mac,” was pure dynamite with a devastating wit thrown in. We ran the food and ammunition to the brigades and regiments like a missile from a German 88mm gun. Incidentally, that gun was so devastating that even looking at it, made some of the boys feel funny. McMurtrie gave me fine management training.

‘The Italian war was rough at times, but we made the most of it otherwise. The allies outnumbered the Germans both in men and equipment but my goodness, those Gerrys, could they make use of the mountainous terrain! The German air force was practically non existent in Italy. Our later mess was good, we dined in a big tent, we were always in the open, and we managed to live off the land; adequate produce, plenty of vino. The newspaper reports about hardships in Italy were often exaggerated. In the evenings we sometimes relaxed under the trees drinking vino and singing songs with the senoras. I initially went to Sicily full of propaganda fed prejudice against the ‘Ities.’ Within 24 hours, I was 100% pro Italy!

Later, in 1946, his great amore, an Italian woman whom he met late in the war, was killed in a motor accident. With his reserve, he’ll tell me no more than that. ‘I’m not going to talk about that because it’s private. I don’t see why I should air my private life.’ But he later relents and offers me his touching notes which say more: ‘The war moved on, Egypt, Libya, Sicily, Italy, always on the move. In Taranto, on the move to Greece in December 1944, Angela d’Ertinorro held out her hand to me. We went to hear the military band play the Warsaw Concerto and Dangerous Moonlight, indeed! I came back from Greece and Angela was waiting. The war ended. Rome. We were both left wing, going to build the brave new world. It lasted until March 1946 and then, as in Carmen, the tocsin sounded. We were partners, never officially married – against her family and my family’s principles we were shacked up. Nobody can ever replace Angela. For 59 years I have thought of her day by day. She is OK, waiting.

‘Since Angela I’ve often been urged to “settle down,” but no one could take her place. I’ve remained restless, parlez vouing from time to time, with a number of distinguished ladies. Once, in a triangle, a gun was pointed at me, but as with the sniper in Italy, the silly blighter didn’t pull the trigger!’’

The writer arrived one interviewing morning to find Ken Birch wearing a brand new Jeppe High blazer. He’s bought it as a joke but enjoys wearing it while he sips a ‘brandewyn’ and we talk. I’ve been away for a short holiday on the Natal, North Coast. On learning this, Birch tells me about a week’s fishing trip to Kosi Bay which he undertook in the thirties with ‘another chap, traveling in a Chev Coupe.’ From the pont over the Usutu River they drove all day through sand to reach Oro point. ‘We camped on the beach. Not a soul about except for some resident blacks from whom we bought eggs and chickens. I never caught a fish, I’m too impatient. When we got to the Sahara I knew how to drive in sand without a four wheel drive.’

Interlude: Birch takes me to see his Civilisations collection in the Unisa library archives. He bustles ahead using his walker. ‘Birch is here!’ he announces, ‘hey, where’s the champagne?’ They know him well those librarians, and they make a fuss of him, but we have to make do with chocolate biscuits before we look at the treasures.

And another: We visit Gordon Leith’s old Reserve Bank building in Johannesburg centre city. It’s been mothballed for decades but now being refurbished for the Gauteng Government’s finance department. The building already reflects its original magnificence. Birch entertains the contractors with his detailed memories. They show him due deference. Then we bustle into Hollard St, Alfred trailing. We storm into the Union Corporation building on which Birch did the detail at the end of the thirties before he ‘joined up.’ We aren’t expected, but he overwhelms and charms everyone and soon we are being given a tour. Later we sit outdoors drinking coffee while Birch regales me with tales of his involvement with the work on the Chamber of Mines building looming nearby.

‘So anyway,’ continues Birch, ‘the war ended. I was demoted from an acting Colonel to an out-of-work. Sadly, the partnership with Angela and Europe was broken and I came back to South Africa. I tried to adapt to a peacetime world. It was a hard time. I drank a lot. But I realized that life must go on. I went back to ‘school,’ to study town planning at Wits. And then, instead of rebuilding the slums of Europe, I got the job of building the new model mining towns as Group Architect for Anglo American Corp. But first, in 1946, I landed a year’s trial partnership with a firm engaged to build the General Mining and Chamber of Mines buildings. I thought the firm I’d joined had the potential to become one of the premier architect’s offices in the city. It soon became clear that the senior partner and I were incompatible. Here I was, a doer, an extrovert, young, fresh from the war and “Uncle Mac,” trying to work with someone quite indecisive. However, as it happened, I teamed up with that excellent Canadian, C S Mclean, who was that year, the president of the Chamber of Mines. He was a mining engineer, a go getter. And we planned the Chamber of Mines building on Hollard St, and we got it done and we got it built; it was well into construction when I left.

‘Meanwhile I thought, is there a future here? I’m getting out; but how? The salary was quite good. I’m not the chap to go around touting for work, to visit pubs and clubs procuring, so how am I going to start on my own? Destiny took over. The senior partner ‘landed’ 45 Main St, for Anglo American Corp, but he dithered. Then the redoubtable Francis Lorne, of Burnett, Tait and Lorne, who had designed 44 Main, the Anglo head office, in the late nineteen thirties and who wished to live in South Africa, took over the commission.’

44 Main Street (The Heritage Portal)

Birch recounts, ‘in 1946, the Anglo American Corporation faced up to opening seven gold mines in the Orange Free State. Sir Ernest and his team decided that in addition to a modern underground development, the surface was also to receive special attention. Francis Lorne was appointed consultant for the architectural planning of the Orange Free State gold mines at Welkom and Allanridge. Lorne needed assistants. I met Lorne and we clicked. Here was my chance and I seized it.

‘Lorne introduced me to my second general in life, Sir Ernest Oppenheimer, leader and humanitarian. An architectural department was formed with me as Group Architect.’ Birch enjoyed working with Lorne, describing him as ‘another time bomb. I look back on my association with him as a very special privilege and reward in life. Lorne was like a wound up spring! Working at AAC with my team was like working in a human beehive. Minimal conferences, to-the-point meetings; a few words and in that way, right up to the sixties, we just got on with the job.’ The very job which, Birch describes as ‘the best architectural job in the country,’ ran for 22 years, ‘a wonderful period!’

Birch’s architectural department became a pioneer in the field of industrial architecture. Before the war, factories just grew. ‘To the best of my knowledge, the 1936 Lion Match factory in Industria and Sappi’s 1937, Springs, Enstra factory, were the pioneer industrial plants. Enstra was designed on modern lines by the civil engineer, Ernst Baumann. We later worked very satisfactorily together. In 1939, Baumann married an attractive girl. They went to the Victoria Falls on honeymoon where their sightseeing plane crashed, killing them both. Baumann might have become the business pal I’ve always sought but never found.

‘Except for the Public Works department in Pretoria, the architectural department of Anglo American was the biggest in the country. It was then not a very easy task to find the 40 architects and draughtsmen to cater for the Corporation’s diverse Southern African building programme. We embraced every kind of domestic, medical, recreational and industrial facility, all based on the slogan – What you require we design. The department built at Welkom, Western Transvaal, Kimberley, South West Africa, Wankie, the Zambian Copperbelt, in Tanzania and Mozambique, and in the Eastern Transvaal, Natal and Johannesburg. In many areas we were confronted with bare veld and at Consolidated Diamond Mines at Oranjemund and Kleinzee, with bare sand; the right challenge for a “Desert Rat.” The department did not produce stereotyped designs. The buildings at Wankie were quite different from those at Oranjemund, as these were from Western Deeps, Bancroft or Premier Mine. The mine buildings, offices, change houses, black hostels and houses, hospitals, recreation clubs and industrial buildings were designed to suit the varying climatic and environmental conditions of Southern Africa.

Although Birch enjoyed a special quality of life in the ‘good old days,’ he’s always known that change is inevitable. About 1965, he became aware that Angela’s and his ‘dreams of a brave new world, were wearing thin. Work standards were dropping; people were deviating from professional standards. The financial world was hit by inflation and currency fiddling. For more than fifty years of his life five US dollars equaled one pound sterling. At Anglo, the vital old guard had gone the way of all flesh; the new seemed pompous and mundane. Fringe benefits became an important component of the salary package leading to petty comparisons. He began to feel sleazy. He took the early retirement package at 55.

In June 2004, Birch said a few words at a gathering to honour his old Anglo friends, Ilse and Norman Morgan. Excerpts from the address capture some of the the spirit of his Anglo days:

Staff member reports to Personnel Dept: Mr. Birch is not a devil, he is the devil incarnate.

An East Rand builder: “We don’t like you. We used to make our money on what was left out of the plans and specifications.”

A staff notice in the architectural office read: This is a democratic joint; you can do or say anything you please as long as the boss agrees with it. [But where would I have got without my staff? I’ve kept a record of all of them and I seem to be outliving them.]

KSB values his long and satisfactory life but regrets that he did much of it alone, sitting on a pinnacle. Harry Oppenheimer always referred to him as ‘the leopard which never changes its spots.’

In 1986, Birch, the experienced industrial architect wrote: I am staggered when I visit houses, office complexes and public edifices with their display of interpenetrating interiors, gymnastic elevations, waterfalls, Babylonian gardens and vast entrance halls with only security guards as occupants. All that seems missing is the Henri Rousseau lion or buffalo peeping through the vegetation. Maybe I’m a frustrated old timer, but to me, somewhere amid this vulgarity, ostentation and virtuosity, the scale of life has been lost. Today we confuse bigness with greatness. He asks, ‘where’s the common sense, where’s the humour?’ [In 2005, he tells me, ‘I’m even more staggered now!’]

KSB devoted many years of his post Anglo life, to heritage preservation. He worked for the National Monuments Commission in the Eastern Cape where for a while, he lived in Somerset East and Grahamstown. During that time he helped ease Ronald Lewcock’s book, Nineteenth Century South African Architecture, into print. His Somerset East house is now the town museum, and the nearby Walter Battiss museum came into being as a result of his collaboration with Owen Eaton, Port Elizabeth architects.

Birch says, ‘when a man pauses during the dangerous sixties, he either turns to the joys of youth or he involves himself with the welfare of others.’ Birch tried both but welfare won! His not inconsiderable fortune allowed him to become a private benefactor of great influence; he turned many ideas into action. He has not been remote from Africa. He grew up in paternal times. His viewpoint changed when he worked from Central Africa southwards, witnessing people coming to grips with post colonial independence. He assisted local groups in their attempts to discover the whys and wherefores of advancement and responsibility. He built rural black classrooms, promoted mathematics, bought books and supported teacher upgrading programmes. As he grew older, he concentrated his efforts in the northern and eastern Cape. Today he is disturbed by the exploitative quality of the ‘system,’ including jerry built housing, the product of aggressive commercial rake off which widens the gulf between ordinary blacks and their ‘global promoters.’ He financed the establishment of a model farm for the Veterinary Department at Medunsa. His funding contributions to his alma mater, Wits University, are extensive. Benefiting from his munificence are the departments of Architecture and Town Planning, Continuing Education, Medicine and Civil Engineering.

John Moffat Building, School of Architecture and Planning, University of the Witwatersrand (The Heritage Portal)

In 1978 the Chamber of Mines appointed him consultant in a working group to establish a Gold Mine Museum in Johannesburg. The original concept was similar to the Kimberley Mine Museum established by De Beers after 1954, and in the establishment of which, together with PRO Fred Bergstrom, KSB had played a pioneering role. In Johannesburg’s case, largesse in the form of land and all the existing facilities and buildings at No 14 shaft, Crown Mines, were donated by Rand Mines at the instigation of Chairman, Punch Barlow.

Birch found the advisory role as opposed to that of authority wielding executive, extremely frustrating. ’It was all dead pan, without spark or laughter.’ Nor is he enthusiastic about the result. His vision, first mooted in his 1936 letter to the Star and later supported by Dr Anna Smith, Johannesburg’s great researcher and onetime Chief Librarian, did not stir the public as he would have wished. The museum, which opened in 1980, was planned to emphasize the astounding history of the Witwatersrand gold discovery, its pioneers and the establishment of the world’s leading mining technologies. Within five years the museum was absorbed into a theme park. Today, when visiting highly commercialised Gold Reef City, visitors can still experience limited underground conditions, they can inspect surface mine activities, but the amusement park rides and the Casino relegate the astounding tale of gold mining to the periphery of appreciation.

The opening of the Gold Mine Museum in 1980 was marked by the issue of a set of prints of KSB’s Witwatersrand mine watercolours, those same prints that brought me face to face with him. Throughout his life KSB kept an artistic record of his local and internationally visited environments. I spent an afternoon in the research section of MuseumAfrica looking at Birch’s watercolour landscapes preserved in plastic sleeves. He was prolific during the 1960s. Street scene after Johannesburg street scene unfolded before me. Here I was, looking at my beloved city through the sharply perceptive eyes of another. Some works were executed at the day’s extremes when he captured the oranges and pinks of sunrise one day, the mauves and purples of a winter’s evening on another. He depicted Johannesburg after an unusual snow fall and many scenes of buildings and trees huddled under towering, summer storm clouds. His Western Cape scenes so accurately depicting blue seas and grey, rock strewn mountains, were, I considered, quite inspired in their capacity to place you right there. Returning the work to storage, I wondered when next someone would enjoy the sheer joy of place that he so well portrayed. The feast of his 93 traveller’s sketch books containing some 3000 drawings, are housed in the Unisa Library Archives. His Eastern Cape scenes are retained in the University of Port Elizabeth Library.

When I asked him how he came to art? he replied with some impatience, ‘how did I come to anything?’ He continued, ‘If I did, it was via heritage and environment. My large and older family offered advantages, practical education and the customs and perceptions of those significant Victorian and Edwardian times. My sisters designed their own dresses and their needlework still adorns the cushions on my settee. Girls were domesticated, boys went for hobbies.’

Birch showed me his childhood exercise books filled with well executed drawings of bridges, roadways, buildings, harbours, railways and maps. Architectural and Civil Engineering inclinations were displayed from an early age. Birch grew up in a time before TV and computer games, when ‘families devised their own stimulation.’

But his painting talent was further inspired by his friend, Siegfried Hahn, with whom he studied at Wits and from whom he learnt the use of watercolours. He claims, tongue-in–cheek, that hours at an architectural drawing board not only designing, but playing bridge and poker, undoubtedly helped to foster an artistic bent. The mentoring of Stanley Furner is also acknowledged. Another major source of inspiration came from the work of famous artist Gwelo Goodman, who, commissioned by Randlord Lionel Phillips, painted many local mine scenes.

It’s disquieting to note how few artistic records of Johannesburg’s mining heritage exist, and that even fewer are available for public viewing. I can remember seeing only one or two mine scenes in the Johannesburg Art Gallery. Birch’s portfolio of fourteen watercolour paintings with an introduction and historical comments on the Witwatersrand and some of its mines, is a valuable but almost wholly neglected piece of Africana. Birch retains two of the 500 sets originally printed; the originals reside in the Hans Merensky Collections, University of Pretoria, together with 120 finished drawings comprising a pictorial History of the Witwatersrand Gold Fields. On reading this manuscript, Birch says to me, ‘Why so anxious? Moenie worry nie, people just want sensation now!’

Birch’s 14 watercolors depict scenes of mine surface workings in their varied seasonal environments. They present a harsh and unique industrial beauty, stimulating my half submerged memories. Let me provide an abridgement of his introductory words: Along the reef today, motorways, supermarkets and the masses of housing and industrial concentrations occupy the attention. There is no longer the opportunity to observe the wonderful contrasts of the Witwatersrand – the tremendous skies, the dry brown winter, the dust and haze of August and September, the brilliant greens of early summer, the January and February thunderstorms and the benign days of March to May... I grew up amidst this beautiful acre of God when its character was still discernable and I have never failed to be fascinated by my homeland. Through my on-the-spot recordings over the years I attempt to pay tribute to the Witwatersrand and its inhabitants, both white and black, whose labour and efforts have made our highveld heritage what it is.

Rietfontein Consolidated Mines (Kenneth Birch Collection - University of Pretoria)

Kenneth Stanley Birch has lived a long time. What do you call someone who’s reached ninety? A nonagenarian? ‘No, a miracle!’ he claims. But in this age of modern medicine, one encounters more and more ‘miracles.’ ‘The lucky ones not buried by surgeons,’ quips Birch. In recent decades, Birch himself has experienced and survived some powerful medical encounters. His long life has been richly interwoven with great events and stimulating characters. His memories, tales and viewpoints cannot but be challenging to today’s people who perhaps cannot afford to look back. In his sixties he ‘went back to the founding Catholic Universal Faith.’ The austere priest, Father Kevin Flood, was another man he ‘greatly respected. A man has a soul as well as a body!’

So at the end, we find Kenneth Stanley Birch fiercely opposed to the permissive and to the blind pursuit of wealth. He sees himself as a rebel with a cause. He’s a man out of step with the modern generation and its relative morality, but is sensitive to their behaviour as reflecting an anxious uncertainty about worldly forces they cannot control. Being a product of Johannesburg’s earlier vitality, he now claims to ‘spend his last days in the suburban zones of living death; dead silent, dead secure.’ His frightened neighbours, ‘pay,’ he says, ‘their millions for a living tomb complete with electric security.’

Birch by his own admission, can ‘talk the hind leg off a donkey,’ All his life he’s spoken his mind. This sometime tyrant and status quo challenger, somehow fears that he will be depicted as ‘having a halo round my shoulder.’ Readers’ might agree, that it’s most unlikely. He’s emphatic, ‘no eulogies or rainbows.’

With all his fire and brimstone, his occasional irascibility, Kenneth Stanley Birch, still loves learning, socializing, gossiping and going about. He visited the Jeppe Schools early in 2006 leaving them collectively richer with a swimming pool, a bursary in memory of a former girlfriend, laboratories and improvements to a library. Will any of theses bequests bear his name? ‘No! That’s boasting.’ He revisits his old Johannesburg haunts which provide him with rich nostalgia. He recalls with obvious delight, his travels all over the world. But he entertains no longing for Europe. He has come full circle: his life’s achievement is linked to Africa. ‘My loyalty is to Africa!’ He’s a man who yet enjoys ‘the astonishment of living,’ one who can still ‘admit mistakes’ and fully indulge his sense of the ridiculous. He engages ‘the enemy’ with an obstinate and redoubtable vigour. He sees himself approaching ‘that undiscovered land across whose bourne no traveler ever returns,’ but he believes the 3000 years old wisdom of King Solomon, ‘The day of a man’s death is his first birthday.’ Straight faced he tells me, ‘I don’t see myself exactly playing a harp in the afterlife, but being a first class concert pianist might be the thing!’

About the author: Mike has spent most of his life in Johannesburg. He earned his living as a human resources practitioner, first in large companies as a manager, [many stimulating years with AECI] and later in his own small HR consultancy. Much of his later occupational time was spent running training courses for managers on how to handle staff within the framework of South African labour legislation, He wrote and published The Manpower Brief, an IR, HR and sociopolitical newsletter, which was popular in many large companies during the 80s and early 90s. A selection of Briefs were incorporated into the book, People Really Matter published by Knowledge Resources. While working, he wrote several business books, one of which, on negotiating, was a sell-out.

In his ‘retirement,’ he has written extensively about Johannesburg, publishing articles mainly in The Star and Sunday Times. Working with Beryl Porter of Walk & Talk Tours, he developed and guided many walking tours around historic Joburg – Braamfontein, Parktown, Newtown, Centre City, Constitution Hill, Kensington & Troyeville, Fordsburg etc. He regularly took visitors to Soweto. His book Johannesburg Portraits – from Lionel Phillips to Sibongile Khumalo, offered popular biographical essays of well known Joburg citizens. His researched paper on Judge FET Krause who surrendered Johannesburg to Field Marshall Roberts during the Anglo-Boer War, was published in the Johannesburg Heritage Journal. The same journal published his series on famous local paleoanthropologists.

Mike is also a widely published poet. Botsotso recently published his third book of poetry, Poetic Licence. His current historical work, published by co-author Peter Delmar of the Parkview Press, The Johannesburg Explorer Book, takes readers on a journey through old Johannesburg, weaving together a history of events and people, which make this city such a fascinating place. His most recent book, a work of journalism, Twelve plus One, featuring transcribed interviews with Johannesburg poets was issued in 2014.

He lived with his wife Cecily, in a century old, renovated house on Langermann Kop, Kensington. A widower since July 2014, he now lives in Eventide Retirement Village in Muizenberg. He believes himself very fortunate in that his son, daughter in law and grandsons live nearby. His daughter lives in Sydney with her husband and son. In case you’re wondering, Luke Alfred, Mike’s son, is the well-known journalist and author.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.