I am always keen to dip into new books on Joburg and this title, Anxious Joburg, caught my attention. Johannesburg is an African metropolis of considerable wealth but also a city of visible poverty. There is a wide gulf between the rich and the poor.

This mix of writers promises an interesting read. The book is a collection of essays by a group of academics from a variety of disciplines: History, Social Anthropology, Psychology, Media Studies, Sociology, Geography, Literary and Cultural Studies and Photography. There are local contributors based at Wits University in Johannesburg but also other authors, perhaps with a South African background who now work abroad – New York, Stanford, London, Sheffield and Harvard. It’s those authors who live elsewhere who perhaps have the basis for comparison of this city with others.

What makes Johannesburg different or unique? The book is based on a study project called “Urban anxieties in the Global South” and the creative juices flow when prospective contributors gather to workshop ideas and share their own experiences of Parktown prawns or life in Derek Avenue Cyrildene. What does the word, “anxiety” signify? Is Johannesburg more “anxious” than other cities?

The foreword by Sisonke Msimang signals that the book is all about the experience of black denizens who migrated to the city and what their experiences were as forced labourers in the mines and living in shacks. It startles that the opening sentence tells us that for black people Johannesburg has always been a place of toil and misery. That is a sweeping statement particularly when supposedly black people in the USA could experience liberty and have dignity restored. It is all too gross a generalization. But stick with it and by the third page Johannesburg is a place of charm, pumping adrenalin because of the unexpected you may happen to encounter any day and just around the corner. There is something of an identity crisis about what Johannesburg is and why it might be a place worthy of close study from a different angle. Msimang describes too her love of Joburg, the city is magical, the moments of audacity and pain are ever present. She argues that this is an important academic study mapping the inner landscapes of the city.

The introduction by Falkof and Van Staden, who have orchestrated the study project, opens with the tension between Johannesburg as the dangerous city and Johannesburg the desirable city. They justify another book on Johannesburg because it is a city of extremes. Any resident of Johannesburg can reel off all of the shortcomings of the city; it is a troublesome metropolis abounding with problems of housing, water, unreliable public transport, dangerous taxis, and potholed roads and for many people because they are poor, the realities of daily life are harsh. The editors see it as an interesting city because of the sharp juxtaposing of luxury living and the poverty of informal settlement. Johannesburg has been much studied and documented and this book makes a contribution to the mapping of Johannesburg as a city of contrasts. Their focus is on the emotional topography. They traverse the complexities of different lives lived in this city and in particular foreground the impact of surviving racism and its legacy as played out in contemporary Johannesburg.

The prism chosen is to study how people experience the city as exhibited through the condition of anxiety. However, I found the definition of anxiety somewhat imprecise. Anxiety appears to be a feeling or a neurosis. Is anxiety a clinical condition with a diagnosis and a possible treatment and a cure or is it a human experience that everyone encounters to a lesser or a greater degree living life, from cradle to grave? All cities induce anxieties but here in Joburg there is every reason to be anxious as you traverse the city. Anxiety means a raised personal defensive awareness that going about in Johannesburg whether in a car or a taxi or on foot could bring you face to face with crime. Everyone I have met will tell you their story of a hijacking, a mugging, cell phones snatched at traffic lights, a break in at a home, being held at gun point etc. When all of that happens, people feel a lot more than anxious.

Reading this book will have you thinking about your own anxious moments; I am convinced that we all, whether white or black, rich or poor have such a story. One of my own - driving from Louis Botha Avenue and halted by a red light on Clarendon Place, taxi ahead, a man with a gun approaches and uses sign language to tell me to open the window on the driver’s side; adrenalin pumps and pulse rate shoots from normal to a zillion in about 3 seconds; instinctive reaction to raise my hands, place elbow on hooter and release the brake to roll the car forward with the conscious intent that a bumper bash into the taxi was better than having a gun to my head; it is an anxious moment - lights change to green, the man with criminal intent evaporates and taxi and my car drive on. Better luck next time! The question for me is how to take precautions against the “next time“ and still continue to live in Joburg.

I think the objective of the editors is to raise awareness about the inequalities of Johannesburg and why poor people who are largely black, have every reason to be anxious about life in Johannesburg as they negotiate the basics of life – transport in taxis, living in crowded buildings, putting food in stomachs, sexual exploitation, being victims of crime, just getting by if you are unemployed and live on the street. Anxieties about city life and indeed the inequalities of this city are so stark because the poor suffer through these hardships of urban life, while white people isolate themselves in walled-in houses, gated communities and have patrolling security squad cars. Yet the paradox is that it is white people who bleat most about the insecurities and are most anxious about the dangers of their lives in the city. The people who have reason to feel extreme anxiousness are the poor black people who in their daily lives have far greater threats and dangers to be confronted and harassed. It seems that a key argument is that hyper visible urban anxiety is a consequence of modernity and that its modern life that makes people more anxious, but there is also the overlay of the racial legacy. I am not convinced - a reading of the city in history throughout the world will reveal that urban life for everyone was filled with unexpected challenges, full of risk and dangers. Is anxiety a perception or is it a reality? In Johannesburg anxiety is reality and the editors set us thinking about that ever present condition.

This book was written prior to the onset of the Covid pandemic which certainly seems to have intensified anxiety in the city. We have gone through months and months of our city going dead as lockdowns were enforced. So there is a sequel to be written about the modern city coping with pandemic conditions, enhanced poverty and a situation where city life then became a breeding ground for a time of madness, violence and mayhem, when shops were looted, people were trampled underfoot and chaos reigned. All conditions which raised the levels of anxiety and have us reflecting on fundaments of inequality, morality, cause and consequence.

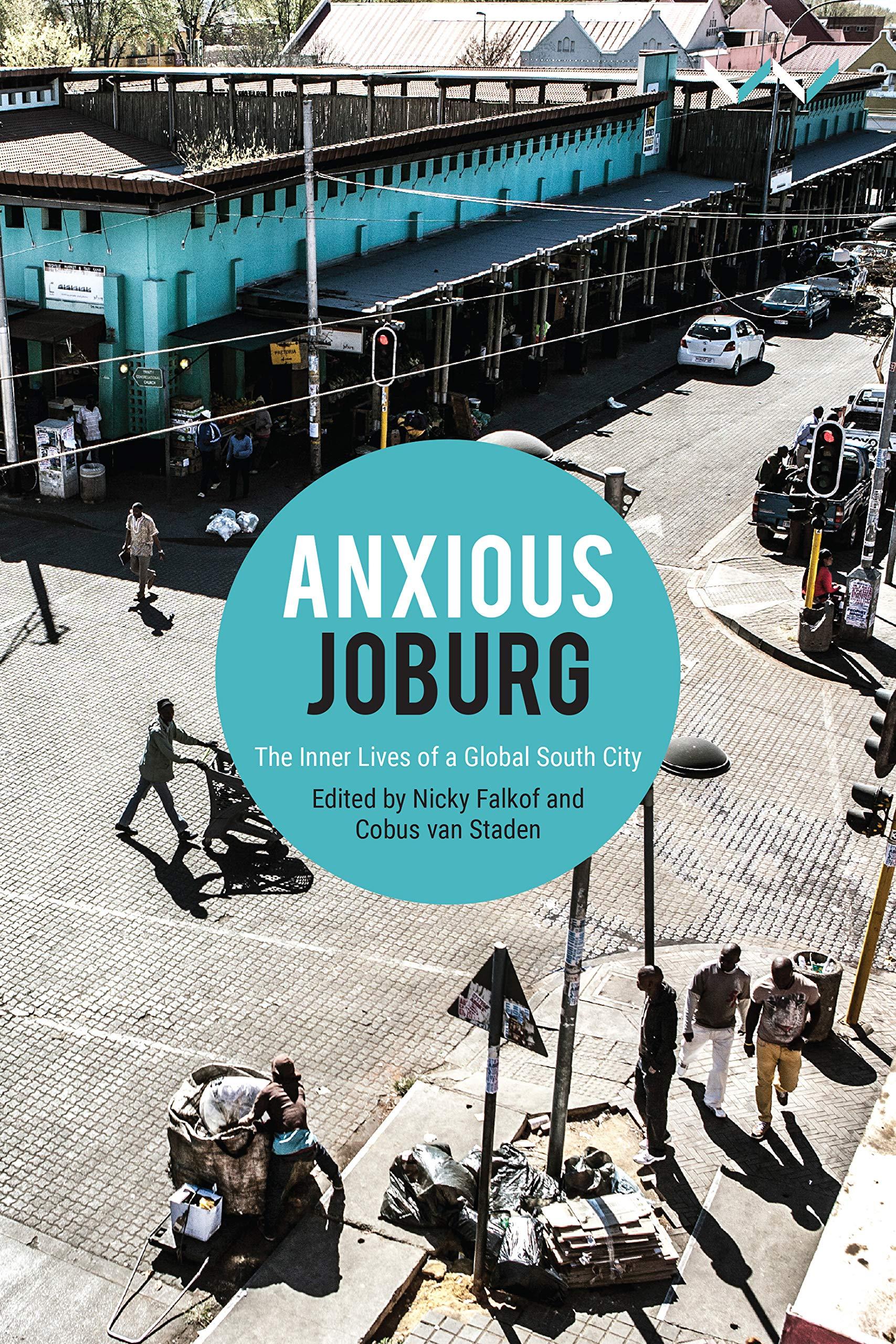

The cover shows the intersection of Raleigh and Rockey Streets and Cavendish Road, Yeoville, with the fairly recent Yeoville Market in the background (a project meant to remove street traders). The picture deserves close study – a mix of parked cars, street furniture, dumped trash, a waste recycler in the foreground, another recycler examining his haul round a pole, someone pushing a trolley.

Book Cover

I suppose the picture was chosen because it is about the underbelly of urban life and there is much in a single picture to be anxious about. The subtitle is ‘The Inner Lives of a Global South City”. So one reads the book with a growing discomfort about the inner lives of the “other half”. Who will be the reader of this book? The outsider looking in or the insider looking out? The reader is more likely to find this book in a university library than to encounter it as street literature or to use it as a guide to navigating the city.

I have questions – why reduce the name of the city to Joburg rather than Johannesburg? Johannesburg, the name of this city, has disputed origin - who were all the men with the name of Johannes who could have had their name attached to the city. That aspect of entomological origin does not interest the authors - there is very little deep history and no chapters on how the city evolved. Instead we take it that the name of the city can be shortened to Joburg - it sounds a deliberate update and a rejection of the earlier history. It is no bad thing to take Joburg for what it is in the 2nd decade of the 21st century – edgy, divided, decayed, dangerous, rich, poor, a cool capital, a place of hijacked buildings, glamourous - these descriptive appellations point to the fractured nature of the city. The luxury of Sandton is juxtaposed against the slum life of nearby Alex.

The Glamour of Sandton (The Heritage Portal)

Second question - what is a “Global South City”? Does this mean that Johannesburg is a city in the Southern hemisphere but with connections to the rest of the world? What is so distinctive about the "Global South” or is it just an in phrase that makes Joburg sound important? So the first problem is knowing the context. Where are the other “Global South" cities? Sao Paulo, Melbourne, Auckland, Santiago, Lima? I am not picking up on any points of comparison to other “Global South Cities“. The reader knows that the term “global south” means something much more substantial than a trendy phrase but more of a discussion of the points of comparison is needed. There is a danger that academic writers use a lingo that is familiar to an inner group of scholars but will be opaque to the wider public.

Do you feel anxious when in another city, whether north or south? Crime is universal and tourists are often prey to the thugs and petty miscreants. So is it a different anxiety we feel when a tourist in another city?

As a group the authors are well meaning and desire a better life for all – and I assume that this is what is meant by “an authentic life"; finding solutions depends on reflections on the conditions of the illness. They know Johannesburg and love the city but are dismayed and distressed at the huge inequalities and the varied manifestations of anxieties. There is a diversity of insights and in line with academic norms much sociological theory detains the reader; my enthusiasm is for the interesting ways of analysing the many experiences of modern contemporary Johannesburg. Perhaps I am asking for too much to wait for the Mayhew of Johannesburg to emerge - the best series for that was the Fourthwall publishers series of 10 booklets, Wake up, This is Joburg.

Johannesburg. Made in China. One of the booklets in the series

For this book the use of the prism of anxiety is an innovative approach and though there might be much to question and to dispute, it is a thought provoking read. Overall this is a challenging and serious study. Tones, moods and voices change as narratives unfold. I wish there was more discussion about solutions and alternatives. The book lacks an economic core and a policy analysis of city government. I don’t see an engagement with or by the town planners, the property developers, the housing companies, transport specialists, city government, architects, city engineers - these are the people who have engaged and continue to engage with the realities of infrastructure provision and trying to find the solutions. They are the ones to match scarce resources to expanding wants to find the finances for redress, investment, employment and economic growth. Anxiety is a touch point for some psychological analysis of what ails the body and mind of the city but solutions will need to excise or apply balm to the condition. So go with the title and take it that Joburg is a city to be put under the forensic scalpel of the social analysts and literary storytellers and it all adds to the mosaic of the city. It is a different addition to a Johannesburg library.

Kathy Munro is an Honorary Associate Professor in the School of Architecture and Planning at the University of the Witwatersrand. She enjoyed a long career as an academic and in management at Wits University. She trained as an economic historian. She is an enthusiastic book person and has built her own somewhat eclectic book collection over 40 years. Her interests cover Africana, Johannesburg history, history, art history, travel, business and banking histories. She researches and writes on historical architecture and heritage matters. She is a member of the Board of the Johannesburg Heritage Foundation and is a docent at the Wits Arts Museum. She is currently working on a couple of projects on Johannesburg architects and is researching South African architects, war cemeteries and memorials. Kathy is a member of the online book community the Library thing and recommends this cataloging website and worldwide network as a book lover's haven. She is also the Chairperson of HASA.