Constance Stuart Larrabee was a 20th century photographer of distinction but is not well known in the 21st century. This book sets out to change perceptions. Constance was born in Cornwall in 1914 and following her parents' emigration to Grootfontein in the then Northern Transvaal, grew up in South Africa. She always wanted to be a photographer and for her this was “the one road to take“, but in fact her life took her down quite a few roads. Photography mattered. In 1933, as a 19 year old, she returned to England to study photography and later chose a spell in Munich, Germany to sharpen her skills. She was in an unusual position to observe the rise of national socialism in Germany and there are two graphic photographs of those political moments of illusion and decision in 1936 Germany.

Constance returned to South Africa in 1936. Following a stretch of professional life in South Africa as an independent young woman photographer, she became a war correspondent in France and Italy in 1944, working with the South African 6th Division and American 7th Army.

Conquering Hero, Rome, 1944, Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington D.C., CGA. 1998.8.68

Constance returned to South Africa at the end of the Second World War and showed her photographic work at a major solo exhibition. She established her own studio and became a fashionable and popular photographer of people, particularly beautiful women in studio poses. In 1947 she was an official photographer of the Royal Southern African Tour in Basutoland. Her best known South African work dates from this period.

However, in 1949 she left South Africa and headed for the USA. Here her road led to romance and marriage to Sterling Larrabee. Constance became an American citizen in 1953. Her life took a different turn as she settled in to new interests on the east coast of the USA. Serious professional documentary photography seems to have slipped into the background as she and her husband sailed, hunted, farmed, and bred dogs. She was still a photographer and had the potential to become a major 20th century American or international photographer. Her photographs, still in black and white, capture the life she lived on Chesapeake Bay. Her best work was on Tangier Island in 1951. She became involved in the arts programme at Washington College, Chesterton. She photographed houses, historic buildings and gardens. All these were quite sophisticated settings. One documentary commission was of Steuben Glass factory in Maryland in 1957. In the USA her South African work was recognized, particularly so her images of rural, African people, and she was invited to exhibit her Tribal Women of South Africa at the Museum of Natural History in New York City. That exhibition later toured throughout the United States and Canada.

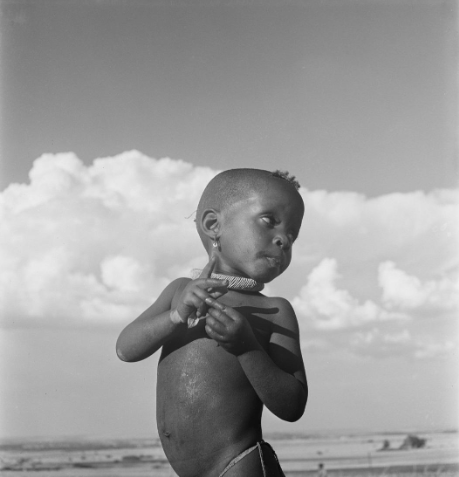

Ndebele Child, Near Pretoria, 1946. EEPA 1998-060411, CSL Collection, NMAfA, SI

She did not return to South Africa for 11 years. Marriage clearly brought its own fulfilment. There was a major retrospective exhibition of her work in South Africa in 1979 at the Johannesburg Art Gallery, the Cape Town National Gallery and the Pretoria Art Museum. This retrospective exhibition showed one hundred photographs. It was a moment in time when her photographs were recognized in South Africa as works of art. “Perhaps the first person in South Africa” to elevate photography to a serious art form“ said one critic.

Johannesburg Art Gallery (The Heritage Portal)

In 1983 her work was included in an exhibition of Ndebele images (with accompanying catalogue / booklet by Natalie Knight and Suzanne Priebatsch). This now collectable catalogue, commented: “1983 marked the return of Constance Stuart Larrabee’s work to South Africa” where she exhibited at the University of Stellenbosch, the South African Association of Arts in Pretoria and at three galleries in Johannesburg, including the Natalie Knight Gallery. In particular the exhibition at the Natalie Knight Gallery focused on the tribal life photographs and included 18 pictures exhibited at the American Museum of Natural History in New York as well as other photographs taken of the Ndebele in the Pretoria district between 1937 and 1947. But as Natalie Knight commented to me: “When we exhibited Larrabee’s work at my Gallery in Johannesburg, there were few purchasers other than myself; I have simply kept all my Larrabee photographs for more than three decades.“ Natalie was definitely one art expert who understood the value of Constance’s photography.

Today the label “ethno photography“ could be attached to much of Constance's work in South Africa, after all she was an educated, professional white photographer observing a culture and a lifestyle that was not her own. In that sense she was the outsider looking in on “tribal life” but her photographs have a timelessness, transcend race and culture and exhibit a dignified respect for the people she photographed. It was said by the Director of the National Gallery in Cape Town of her 1979 exhibition: “The unique element in these photographs is the quality and deep human sympathy which is evident in them”. Her images were moving and memorable because of those qualities, along with her mastery of light, pattern and composition. This is where her European training, particularly in Germany gave her the edge. There were several later exhibitions of her work in the USA, celebrating her African work and her USA years. She died in the USA in 2000 and her artistic estate was left to six American museums and institutions, linked to the Smithsonian.

It is tragic that this extraordinary photographic artist should have produced great photographs in Southern Africa, but other than the small collection at the Brenthurst library it would appear that her work is not held in the public collections in Cape Town, Johannesburg or Pretoria. Her artistic estate has been lost to South Africa (it must be noted that Natalie Knight has perhaps the largest private collection of Larrabee works). This is a photographer who preceded David Goldblatt and Peter Magubane and her work is also reminiscent of their documentary photographs of the South African scene. Within her own lifetime her work can also be compared to that of Margaret Bourke White.

Brenthurst Library (Kathy Munro)

I am immensely grateful to Peter Elliott for finding Constance Stuart Larrabee and telling her story. It is clearly a labour of love and ferret like research. The archival material was very limited and he has made the most of what he has found. Elliott has taken the interesting journey to locate the photographs, journals and work of his subject. The book, produced in paperback format, is a sombre presentation in black and white of her photographs. It is most effectively designed and will become a classic photographic collector’s item.

Book Cover

His commentary though insists on understanding the South African political condition through the racial prisms of privileged whiteness and impoverished blackness; and even Alan Paton is lambasted for living a life of white privilege. South African history is multi-layered and rooted in historical complexities. Paton’s Cry the Beloved Country, had an enormous American impact (don’t forget the musical Lost in the Stars). I read Paton in an American senior school English textbook in the mid-west of America at a time when the Civil Rights movement was forcing through a new consciousness about racial discrimination in the US. Paton’s story about South Africa gave American school children a new introspection.

Nevertheless, Elliott has had a lifelong interest in history and art. He discovered Constance when he was researching the story of the South African forces in the Apennines in Italy in the winter of 1944-45. He wanted to know more about this war correspondent cum photographer and to place her work in a context. Although he wishes his reader to see her as a driven, career photographer, taking a single road, the story he tells is of a woman who allowed her art to slip into a secondary hobbyist space following a happy marriage (yes, there were moments when her creativity reasserted itself in her photographic images of life on the eastern shores of Maryland).

I recently purchased a copy of the best of Time Life photographs of the 20th century; Constance should have had work and recognition in news magazine work in the USA in the second half of the twentieth century but she was not there on those great American historic moments of politics, peace and war. It’s her African and wartime photographs of the first half of the twentieth century that earn her a place in the making of photography as an art. The sadness is that when Constance exhibited her work in South Africa in the seventies and eighties, photography as an art form to be purchased and collected had not even then been widely recognized. Elliott is to be congratulated on finding and reviving the story of her life. I hope that an exhibition of her work will be mounted in South Africa in 2019. Her art has come of age and she deserves this posthumous homecoming and recognition.

Constance Stuart Larrabee (via wikipedia)

Images - Ndebele Design and Ndebele Child, Constance Stuart Larrabee (CSL) Collection, 1998-006, Eliot Elisofon Photographic Archives, National Museum of African Art (NMAfA), Smithsonian Institution (SI); and Conquering Hero, Corcoran Gallery of Art.

Kathy Munro is an Honorary Associate Professor in the School of Architecture and Planning at the University of the Witwatersrand. She enjoyed a long career as an academic and in management at Wits University. She trained as an economic historian. She is an enthusiastic book person and has built her own somewhat eclectic book collection over 40 years. Her interests cover Africana, Johannesburg history, history, art history, travel, business and banking histories. She researches and writes on historical architecture and heritage matters. She is a member of the Board of the Johannesburg Heritage Foundation and is a docent at the Wits Arts Museum. She is currently working on a couple of projects on Johannesburg architects and is researching South African architects, war cemeteries and memorials. Kathy is a member of the online book community the Library thing and recommends this cataloging website and worldwide network as a book lover's haven.