Gordonia is a remote, frontier part of South Africa, located in the Northern Cape Province. It is a dry, mainly barren, marginal land with a small linguistically and culturally mixed population. Along the Orange River the land is fertile because it is irrigated. It was an area settled by the Basters (in the late 19th century but there are also Xhosa speakers and descendants of other Khoisan people). Frontiers people are a breed of their own, self-reliant, tough, hardy and poor. The frontier is an important part of South African history and we are reminded that there were northern frontiers in addition to those of the eastern Cape.

This book is a collected set of essays about the 19th and 20th century history of the area by the late Martin Legassick. It is Legassick’s last work. Most of the essays have been published previously in academic journals. However, the value of this book is that it brings together a sizeable body of historical work, is a tribute to the scholarship of Legassick and contributes to the local history of the Northern Cape. As such it makes a contribution to the development of a new, alternative history of South Africa that challenges the colonial past. The book also extends our grasp of heritage and, because of the activist approach of the author, effectively illustrates the link between heritage, history and the ownership of the past. New histories make for new heritage.

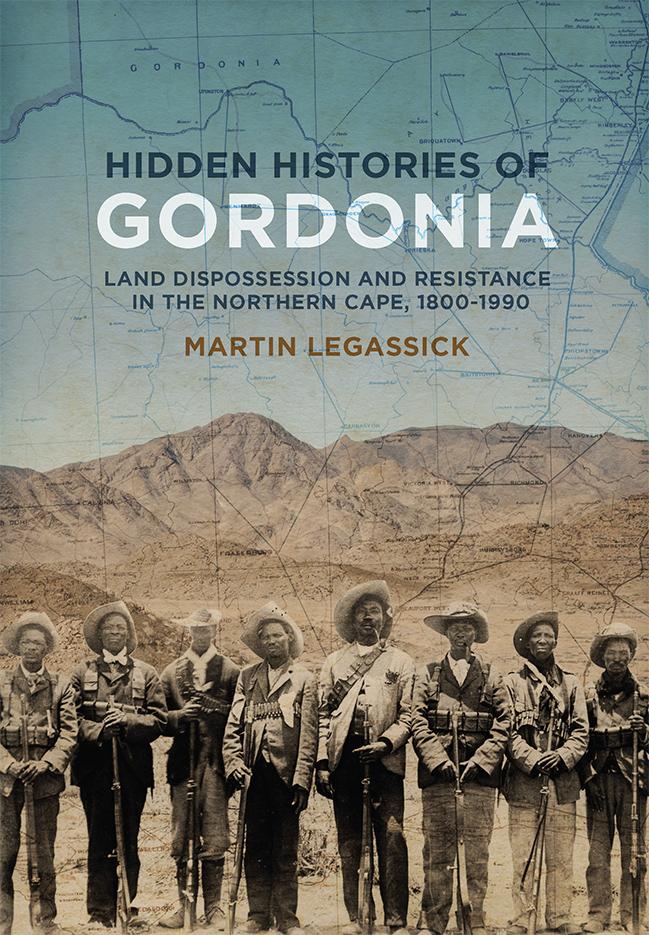

Book cover

Legassick’s history is grounded in field trips and personal exploration undertaken in the 1990s; his work builds upon and complements Nigel Penn’s “The Forgotten frontier: colonist and Khoisan on the Cape’s northern frontier in the 18th century” (2005). Legassick considered himself to be an applied historian and his efforts show that well grounded historical research and writing is of relevance to the lives of people in the present. He writes to inform “transformation in the present on the basis of evidence from the past” with the direct objective of addressing past injustices in support of land claims or compensation.

The colonial occupation of Gordonia starts with the indigenous history but also illustrates the northward movement and creation of settlements of Basters and whites from the western Cape. It was an area without boundaries other than the natural boundary of the Orange River. The British colonial efforts to impose law and order is shown in the names Gordonia (named for Sir Gordon Sprigg four times Prime Minister of the Cape Colony between 1878 and 1902) and Upington (founded in 1884 and named for Sir Thomas Upington, Attorney-General and then Prime Minister of the Cape). It was a part of the world that remained remote and barren and bred frontiersmen of all colours. In fact, the frontier mentality and determination to survive in inhospitable conditions reveals a greater common identity than the bewildering array of racial demarcations divide.

Legassick’s interest is in case studies of ordinary people, such as members of the Baster September family. Abraham Baster was a former slave and was the first person to lead water out of the Orange River for irrigation purposes and it is Legassick’s work that has led to recognition of his pioneering efforts. The representations and treatment of the so-called “Bushmen” between 1880 and 1900. One can’t but be shocked by the account of the late 19th century illegal trade in skeletons dispatched to the Natural History museum in Vienna and for purposes of ‘scientific’ research. I was interested in the link between the academic work of the Bleek family and the fact that as late as 1911 Dorothea Bleek participated in the collecting of human remains as related in the Weintroub biography of Bleek (click here to read a review). It is this kind of “hidden history” that results in applied revisions and it is difficult not to be judgemental even when taking account of the standards and norms of another era because there were severe consequences for racial stereotyping and disrespect of individuals and groups.

A fascinating chapter on the “brown” Afrikaners of a remote spot called Riemvasmaak (which came to prominence in 1974 when a community of 1000 was forcibly moved), shows their origins through migration, colonization, war and revolt. The Marengo Rebellion of 1903-07 is a well told tale of resistance, surrender and heroic last stands. The fluidity of the border of the Northern Cape and German South West Africa speaks to the politics of space and demarcations, cooperation and conquest. Borders only matter if they can be enforced but borders also turn rebels into refugees.

The uniting themes of the collection of seemingly disparate essays is that of land occupation, dispossession and resistance. Legassick’s skill as an historian shifts people from dubious frontier characters to individuals with a history worth recording. It is important to recover the history of reserves, mission stations, farms and conquest to support modern day land claimants and subsequent restitution. Hidden histories are about racial segregation and people treated as pawns in both colonial and apartheid eras. Governments mattered because they counted and classified, drew maps and imposed taxes.

The strength of the book lies in Legassick’s command of the history of the area and the ease with which he moves through several centuries at the same time as explaining why history matters today. The problem with a book of essays is that they are standalone entities and there are some obvious gaps. Absolutely essential to any historical study has to be an investigation of the economic life of the people. How did they make their living? Farming on irrigated land requires capital investment - where and how can capital be found? How did the Orange River wine industry emerge? What mining activities took place? One returns to the low population figures and one wonders whether current demographics and economic circumstances promote migration.

The two map reproductions of 1801 and 1882 are unreadable and add nothing to the book. The figures and small maps of Upington are examples of poor reproduction. The book would have been enriched with more of a photographic record. In contrast the chapter end notes, the comprehensive bibliography and the index pulls the book back towards acceptable and strong academic standards.

The interest of this collection of essays extends well beyond the Northern Cape. This is a book that matters to South African history. I recommend this book for the breadth of coverage of the essays, but also the way in which the study of detail then contributes to an understanding the whole. It is an important historical study and stands as a memorial to the author who was an accomplished historian and compassionate activist. Legassick’s historical methods and careful research are an inspiration to other local historians interested in the small man.

Kathy Munro is an Honorary Associate Professor in the School of Architecture and Planning at the University of the Witwatersrand. She enjoyed a long career as an academic and in management at Wits University. She trained as an economic historian. She is an enthusiastic book person and has built her own somewhat eclectic book collection over 40 years. Her interests cover Africana, Johannesburg history, history, art history, travel, business and banking histories. She researches and writes on historical architecture and heritage matters. She is a member of the Board of the Johannesburg Heritage Foundation and is a docent at the Wits Arts Museum. She is currently working on a couple of projects on Johannesburg architects and is researching South African architects, war cemeteries and memorials. Kathy is a member of the online book community the Library thing and recommends this cataloging website and worldwide network as a book lover's haven.

Review copy kindly provided by Wits University Press.