Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

For more than 150 years, airborne cameras have produced awe-inspiring images of our planet, revealed the devastating scale of natural disasters down below, consequences of ugly wars, tipped the scales in combat, assisted in studying plant ecology, identifying archaeological spots, constructing maps and much more.

Eventually underpinned by militaristic surveillance, aerial photography became a world tendency that took off 30 years after the invention of photography. Aerial photography immediately attracted photographic pioneers, who captured exquisitely composed aerial photographs.

This article primarily focuses on South African aerial photographic history but also had to deviate into a neighbouring country by including a crucial historical portion related to aviation activity during the conflict between South Africa and the Germans in early Namibia during World War I.

In support of this article, aerial photographs, spanning 70 years were either extracted from the Hardijzer Photographic Research Collection (HPRC) or relevant web pages.

First, a brief reflection on the world history of aerial photography.

1. Brief World history – Aerial photography

Not long after commercial photography was invented “adventurous amateurs” launched cameras into the sky using balloons, kites, pigeons, and even rockets.

- Gaspar Felix Tournachon, more commonly known as “Nadar,” is credited with taking the first successful aerial photograph as early as 1858 from a hot air balloon tethered 262 feet (80 meters) above Petit-Bicêtre (now Petit-Clamart) just outside Paris. Sadly, these original photographs have been lost.

- Two years later (1860), the first American to capture the oldest surviving aerial photographs was James Wallace Black. These images were also taken from a tethered hot air balloon, the Queen of the Air, 2000 feet (610 meters) above Boston. Black is best known for his later photographs of the devastating Boston fire in 1872.

Elsewhere in the world, aerial photography pioneers were experimenting with other methods.

- In 1903, German engineer Alfred Maul demonstrated a gunpowder rocket that, after reaching 2600 feet (some 790 meters) in just eight seconds, jettisoned a parachute-equipped camera that captured images during its descent.

- That same year, German apothecary Julius Neubronner, curious about his prescription-delivering pigeons’ whereabouts, strapped cameras to his birds to track their routes. Neubronner also used his pigeons to take photos of the 1909 Dresden International Photographic Exhibition, turning the resultant photographs into postcards.

- Piloted powered aircraft were first used for aerial imagery just a few years after the Wright Brothers’ first flight in 1903. Cinematographer L.P. Bonvillain took the first known such photo in 1908, photographing from an airplane over Le Mans, France, which was piloted by none other than Wilbur Wright himself.

- The first known photo from space, depicting a glimpse of Earth, was taken on 24 October 1946.

During the late 18th century, aerial photographic views of large cities such as Paris, London, Melbourne and New York became commercially popularised. This honour would only be partly achieved in South Africa by 1911.

2. Aerial Photography Defined

Aerial photographs entail taking photographs from an aircraft or any other airborne platform.

While many incredible photographs exist taken from elevated vantage points such as mountain tops, high-rise buildings, towers, cable cars and such, they do not fall into the category of aerial photography.

Aerial photography has been used in recording, mapping and surveillance. Contemporary aerial photography has a diverse field of application, such as in geology, irrigation and forestry, railway and roads, and mining. They also play a role in planning infrastructural projects, agricultural production and urban development. Accurate topographical maps remain indispensable to the government, engineers, land surveyors, geology students, property owners and the general public. They also remain a military necessity.

Aerial photography is further used in regional analysis and evaluation of specific sites. It also provides a historical perspective that allows us to view landscape changes over time.

In short, aerial photography is an optimal tool for observation and research.

Unlike a generalised line map, almost all detail is visible in an aerial photograph. The user, although unable to make accurate measurements from the photograph, can perform an interpretation of what exists on the ground.

Diverse image forms and formats originate from aerial photographs, including vertical, oblique, contact prints, mosaics or enlargements, topographical map sheets, flight plans, line drawings and sketches.

Stereo photography was also not unusual in this field. Aerial stereograms are created from pairs of photographs that show the exact same location but from slightly different angles. By viewing the photo pairs through a stereoscope, the brain is tricked into seeing or perceiving an impression of heights and depths.

Rozzi (2019) states that aerial photography has a distinctive image form. They appear obscure, highly encoded and hard to “read,” understand and make sense of. This view would be in reference to topographical, straight-down imagery. They are ambiguous at best, simultaneously evocative yet aesthetically appealing, but strangely blank in their metric layout. While the larger perspective is comprehensive, their legibility is all but obvious, yet – depending on image scale, quality and resolution – limited in detail.

Rizzo (2019) adds that aerial photography establishes a visual contact for individual features on the ground, places them in relation to one another and a broader topography, and, crucially, reveals patterns to the eye.

While aerial photography produces decent overhead images providing a general sense of an area, it lacks the precision necessary for most surveying jobs in that it does not show the topography. For that, photogrammetry is required.

Modern photogrammetry involves taking multiple images of a feature and using them to create digitized high-resolution 2D or 3D models from which accurate measurements can be deduced. Depending on the project’s scope, a model made with photogrammetry may require anywhere from a couple hundred to several thousand separate images.

Aerial photography is not to be confused with aviation photography. Aviation photography has the primary intention of capturing aircraft in flight. Types of aviation photography include air-to-air, ground-to-air, ground-static, and remote photography. Photographing aircraft crashes would also fall into the category of aviation photography.

In aviation photography, when photographing aircraft in flight, land captured below only becomes secondary. This article includes two examples of aviation photographs showing aircraft in flight with views of some land below.

Earlier photographers from the South African Railway Publicity Department produced many aviation photographs. Britain’s Charles E. Brown is renowned for the aviation imagery he created (Harold, 1983).

Example of an oblique aviation photograph showing 4 Westland Wapiti aircrafts flying over the west of Pretoria during 1933. These same aircraft were also used in aerial photography. Down below the Pretoria West power station and early ISCOR development can be seen.

Oblique aerial photograph showing a Douglas from the SAA flying over Johannesburg. Photograph by unknown photographer employed by the South African Railway Publicity department. Image via Drisa,

3. Types of aerial photographs

Aerial photography can be categorised into two distinct categories, namely Vertical and Oblique aerial photography (low and high).

3.1 Vertical aerial photography

Vertical orientation aerial photographs are photographs that are taken straight down. They are mainly used in photogrammetry and image interpretation. Photogrammetry pictures are traditionally taken with unique large format cameras with calibrated and documented geometric properties.

The resultant images are typically used in cartography (particularly in photogrammetric surveys, which are often the basis for topographic maps), land-use planning and aerial archaeology.

Due to their abstract nature, vertical photographs have more of a practical application versus a commercial value. They are, therefore, not as well circulated (or freely available) as oblique aerial photographs. Oblique photographs have a significantly better visual appeal.

For this reason, this article includes more oblique aerial photographs compared to the “duller” vertical photographs.

Vertical aerial photograph of unknown South African location, neatly mounted on cardboard. Vertical photographs have less of interest compared to oblique aerial photographs in that an untrained eye may find it challenging to decipher. Photograph by unknown photographer.

3.2 Oblique aerial photography

Oblique aerial photographs are photographs taken at an angle. They can be taken from either a low or a high angle.

Photographs taken from a low angle relative to the earth's surface are called low oblique, whereas photographs taken from a high angle are called high or steep oblique.

Oblique aerial photography has endless uses, such as in movie production, environmental studies, power line inspections, construction progress, commercial advertising, conveyancing and artistic projects.

An international example of aerial photography used in archaeology was the mapping project done at the site of Angkor Borei in Cambodia from 1995–1996. Relying on aerial photographs, archaeologists were able to identify archaeological features, including 112 water features (reservoirs, artificially constructed pools and natural ponds) within the walled site of Angkor Borei.

South Africa has its own example in the form of a pre-colonial city, namely Kweneng (Suikerbosrand), in which aerial archaeology played a significant role.

The public would have better access to oblique aerial photographs because they have a better visual appeal and commercial value.

Very detailed oblique aerial photograph of Sunnyside in Pretoria. Captured by Dotman Pretorius during 1960s. Amongst other, Esselen street can be seen on the image. The Sunnypark shopping centre was still to be built.

Oblique aerial photograph captured by Lynn Acutt’s of the Durban bay and bluff during 1957.

Oblique aerial photograph taken during 1957, showing the Bloemfontein railway workshops. Photograph by unknown photographer employed by the South African Railway Publicity department. Image via Drisa.

Oblique aerial photograph showing the Durban harbour during 1935. Photograph by unknown photographer employed by the South African Railway Publicity department. Image via Drisa.

4. Southern African Aerial Photography History

Ironically, not much research has been done on the history of South African photography in general. The one exception, however, is aerial photography. While the information on early aerial photography is not cohesive from a historical perspective, much information on this topic is available online. The interest in the topic is primarily aviation related.

Southern African Aerial photography history can loosely be divided into four categories, namely:

- From first use until the end of World War I (1918)

- The period between the two World Wars (1918 – 1939)

- World war II (1939 – 1945)

- Period post World War II (1945 – the 1970s)

Due to aerial photography having a reconnaissance focus during periods of conflict, the periods between the two world wars and post-World War II have become less romanticised.

4.1 From first use until the end of World War I

While the southern African history around aerial photography for this era still requires ongoing research and historical verifications, this era was characterised by the gradual recognition that aerial photographs could be used for surveillance and mapping.

The development of southern African aerial photographic history was marked by the commercial balloon ventures in Durban, a Swiss balloonist and photographer presence in Johannesburg and three conflicts, namely the Anglo-Boer war, the German South West Africa campaign and World War I.

4.1.1 Anglo-Boer War

Nesbit (1996) refers to a British Balloon unit headed up by Major Elsdale that travelled to Bechuanaland (Botswana) and the Northern Cape during 1885 as part of an expedition to repel Boer incursions. While Elsdale experimented with cameras fitted to three balloons in England during 1883, no record exists of photographs captured while the balloons were in Bechuanaland (Botswana).

Lee (1986) also refers to the British army that brought several hydrogen-filled balloons for reconnaissance to South Africa during the Anglo-Boer war (1899-1902). The primary function of the balloon sections was to collect intelligence about Boer movements during 1899 and 1900. One of their most important but less published roles was to improve the British situation due to poor maps the British had of South Africa at the outbreak of war and to sketch Boer camps and battle positions. Lee (1986) adds that the potential of these balloons was not fully realised in that the observers could have been trained as photographers.

At the same time, Lee (1986) includes an aerial photograph allegedly sourced from a Durban-based museum. This single glass-plate negative, he claims, may well have been the earliest South African aerial photograph. Lee confirms that the photograph was verified by a retired RAF reconnaissance officer, who “agreed that it appears to be a genuine aerial photograph.” What was not confirmed was whether this was an aerial photograph originating from the Anglo-Boer war.

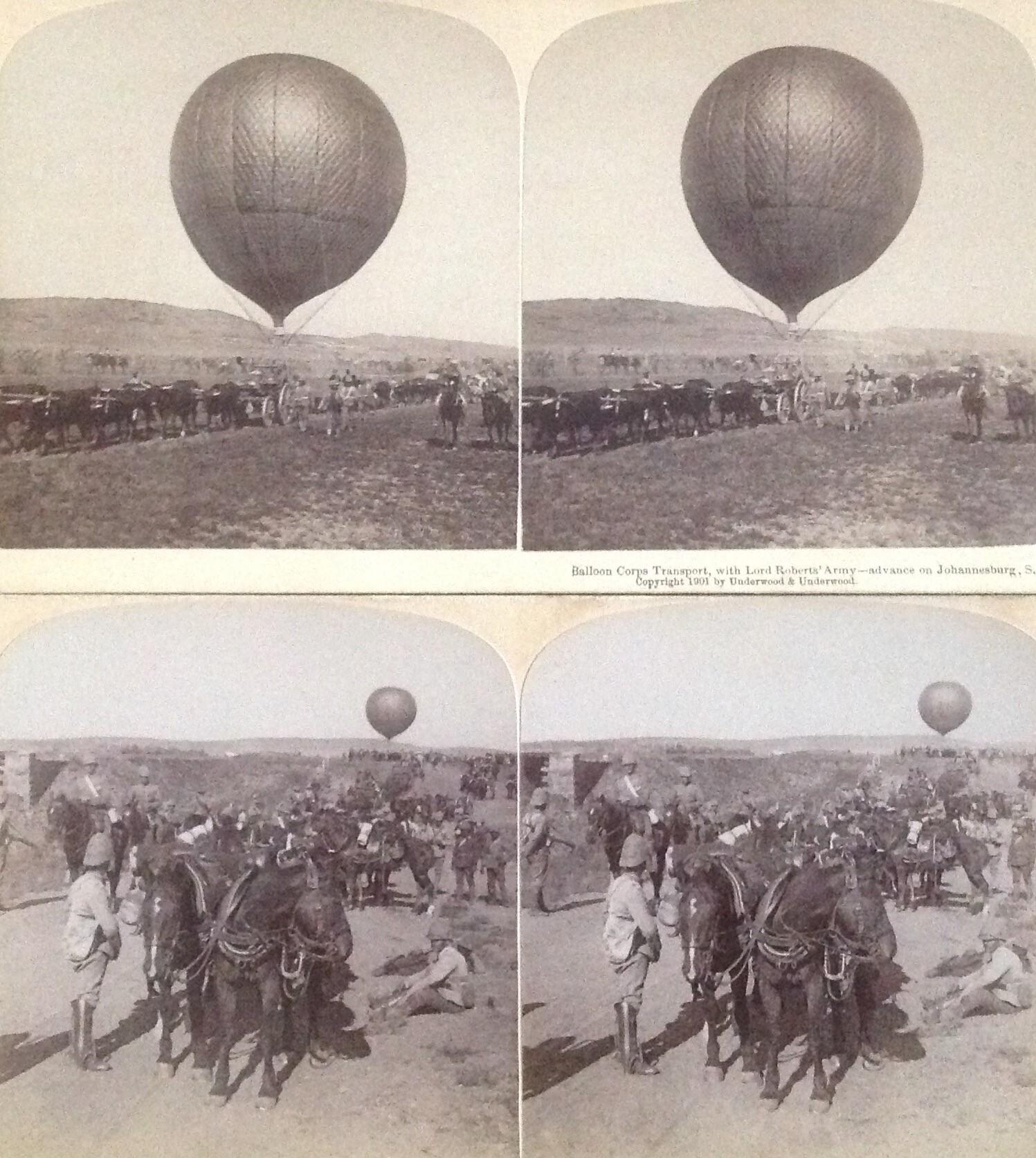

This photograph, which appeared in “With the Flag to Pretoria”, provides a sense of balloon reconnaissance activity during the Anglo-Boer war. The balloon basket hardly allows for enough space (and stability) to take up bulky photographic equipment.

The photograph Lee presents is of reasonably decent quality, taken at one thousand feet (305 meters), allegedly showing a military camp of an infantry battalion, a cavalry or mounted infantry regiment and a headquarters or administrative unit.

This, however, turns out to be incorrect. The image Lee relied on as potentially the first South African aerial photograph, captured during the Anglo-Boer war, turns out to be a photograph captured during the South West Africa campaign. Illsley (2012) and L’Ange (1991) use this same image in their respective works confirming the South West Africa link. The RAF reconnaissance officer Lee relied on to verify the image was correct; it was a genuine aerial photograph, only from 15 years later. More about this image later.

Having determined that the photograph in question was not from the Anglo-Boer war era then begs the question, were aerial photographs captured from the British balloons during the Anglo-Boer war?

An answer to this question is possibly provided in Captain JB Jones’s diary of their activity as a balloon unit during the Anglo-Boer war. Jones, of the Royal Engineers, headed up the No 1 Balloon section. In his diary, he references the balloons that could take up two men, cramped in a wicket basket. He described the work done by the section as “captive work,” which included sketching. In this diary, one entry appears of photographs taken on the afternoon of 28 February 1900 (Cormack, 1990). It is unclear whether this is in reference to photographs taken on the ground or from the air. No further reference to the taking of photographs has been identified in his diary, which strongly indicates that capturing photographs was not a primary focus of the unit.

In “With the Flag to Pretoria” of 11 December 1899, one photograph was published taken from a balloon. This is an image showing soldiers on the ground holding the balloon down. While the image, in all probability, could not be described as an aerial photograph in that it was only taken at the height of some one hundred feet (30 meters), it does confirm that cameras were taken up in balloons.

This particular photograph in itself certainly provided no valuable reconnaissance information. Could the soldier who potentially captured the photograph have taken up a camera up on behalf of a journalist, who later published it in the magazine?

Bensusan (1966) provides the answer, where aerial photographic activity can be safely linked to a British war correspondent, HC Shelley. Bensusan states that on 11 December 1899, Shelley was instructed to take his camera up in a balloon. He allegedly used a 5 x 4-inch folding Kodak camera at a fixed focus of infinity and stopped down at F.22. Although a hand-held camera, Shelley recommended a carrier for firm fixation of the camera in position while up in the air. His first pictures were reported as successful and led the way to frequent use of balloon telephotography, particularly at Paardeberg, where the Boers were confined in the riverbed.

It was the custom for balloon observers to send down messages in a canvas bag while still aloft, but photographic reconnaissance was now being considered more seriously, resulting in canvas bags being sent down immediately containing exposed film.

In February 1900, the new weekly London magazine King produced a unique set of Shelley’s balloon pictures taken from a considerable height. To date, I have been unsuccessful in sourcing this magazine and images.

This photograph, which appeared in “With the Flag to Pretoria”, hardly qualifies as an aerial photograph. If accepted as an aerial photograph, it may well be the first known record of an aerial photograph on South African soil in that the photograph does confirm that a camera was taken up in a balloon during the Anglo-Boer war. This photograph was captured from a height of some 30 meters and shows five British soldiers below, one holding onto the balloon with a rope. Considering the shades of the soldiers, this photograph was either taken early morning or late afternoon.

Based on the above, the unaspiring photograph of British soldiers below, if accepted as an aerial photograph, officially becomes the first aerial photograph captured during the Anglo-Boer war – until proven otherwise.

The reality remains that:

- A British journalist captured the first South African aerial photograph during the Anglo-Boer war;

- British soldiers were not trained to conduct aerial photography while in South Africa;

- which also means that they would not have had unique cameras required for capturing aerial images;

- photography in the earlier years required prolonged exposure times. Any movement would have caused a blurred picture;

- time (and opportunity) to develop photographs would also have been restrictive, resulting in delays. By the time a photograph was developed, aspects on the ground relating to Boer activity would have changed.

As an avid collector of original Anglo-Boer war photographs, I have not encountered any original aerial photographs from the Anglo-Boer war period. Would these possibly be found in a British military museum?

Two stereo photographs by Underwood and Underwood showing the British balloons in use during the Anglo-Boer war. Whilst one balloon commander made a diary note entry stating that photographs were captured on 28 February 1900, it is unlikely that this was in reference to photographs being taken by soldiers from the balloons.

4.1.2 Commercial venture by Spelterini

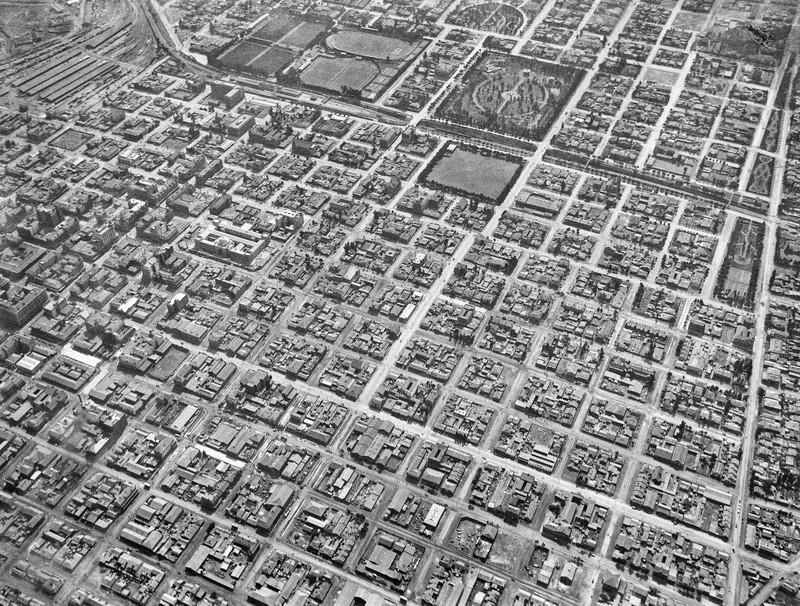

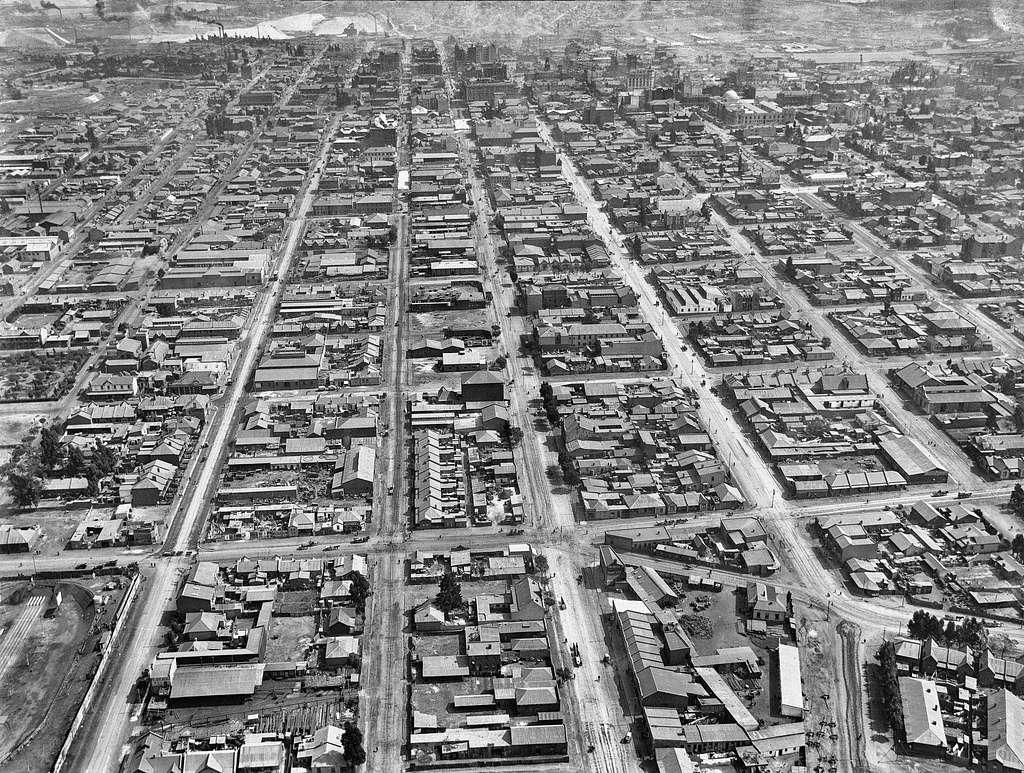

The first professional (and commercial) South African aerial photographs were captured by the Swiss balloonist and photographer Eduard Spelterini (born Schweizer). Outstanding oblique aerial photographs of the world's premier gold mining city, Johannesburg, were later published by him.

He photographed the Johannesburg mines from his balloon in 1911. It was certainly not easy to capture photographs with equipment weighing between 40 and 60 kilograms.

Part of the batch of the first commercial aerial photographs of South Africa, showing Johannesburg, captured from a balloon by Swiss photographer and balloonist Spelterini (1911). The Johannesburg High Court which opened a year prior to this photograph been taken can also be seen. Photograph via Goodfreephotos.

Part of the batch of the first commercial aerial photographs of South Africa, showing Johannesburg, captured from a balloon by Swiss photographer and balloonist Spelterini (1911). In the background goldmining activity can be seen. Again, the Johannesburg High Court can be seen at the top right of the photograph. Photograph via Swiss archives.

4.1.3 Durban balloons

Illsley (2003) also references two different balloons used at Ocean Beach (Durban) in two separate instances, one during 1911 and the second during 1912. This commercial venture took thrill-seekers into the air to view the city from one thousand feet above. While I have not seen any such images yet, it is suggested that the same balloons were used as a photographic platform from which several fine aerial photographs of Durban were allegedly captured.

Illsley adds that in each instance, the balloons were wrecked by coastal weather after just one day of commercial activity, meaning that photographs taken during these two days of balloon activity would be scarce.

This raises a curious question? Who was the photographer of these images? Could this have been South Africa’s first aerial photographer?

4.1.4 World War I and the German South West Africa campaign

The first purposeful southern African aerial photographs taken from an aircraft are thought to have been those captured during the South West Africa campaign. Illsley (2012) uses the very same image Lee (1986) used, however, confirming that this was an image that was captured during the South West Africa campaign (1915). This image, he claims, was captured by the German officers from their aircraft in use at the time.

The German officer Fiedler was a pioneer not only in bombings but also in aerial photography in South West Africa, and his pictures of the Union troop dispositions were handy to the Germans in planning their tactics against the South Africans (L’Ange, 1991).

South Africa was asked to invade the neighbouring German colony of South West Africa (today, the Republic of Namibia) as a British dominion. The German colonial forces had only a pair of aircraft at their disposal. One of these, an LFG Roland, flown by Lieutenant Paul Fiedler, was used to undertake several bombing raids on South African camps. One of which, at Tschaikaib, he managed to photograph, despite his biplane being under fire from South African troops (See photograph below).

South African Aviation Corps (SAAC) operated the invading South African forces’ aircraft. The biplanes of the SAAC were used as reconnaissance aircraft over the Namib desert and did not undertake any aerial photography.

Van der Westhuizen (1996), however states that Major Ireland-Low became South Africa’s first aerial photographer in that it has been suggested that even before the SAAF being established (in 1921) that Ireland-Low took aerial photographs with a wooden camera during 1915. He seemingly photographed the Southern tip of Africa, which he took for British Forces under command of General Smuts. It is not clear whether this is in reference to activity in Namibia.

This remarkable photograph has incorrectly been linked by some as an Anglo-Boer war aerial photograph. This photograph was however taken 15 years later during the South West Africa campaign (1915) over Tschaukaib at a hight of 6000 feet (1830 meters) and is viewed as one of the first aerial photographs captured during wartime. It was in all probability captured by the pilot, lieutenant Fiedler himself during the bombing raid over Tschaukiab. At the left is the rail line and Tschaukaib station. The South African tents and trenches are clearly visible. The two larger clouds of smoke are from bombs and in the top right-hand corner a smaller puff of smoke can be seen as a 4,7-inch gun fires at the aircraft (image via Illsley article)

World War One (1915) - German South West Africa. This unusual postcard shows German officers Fiedler and Von Scheele standing next to a LFG Roland aircraft that would have been used to photograph and bomb South African positions.

Aerial photograph in picture postcard format showing Keetmanshoop from above – 1915. The photographer in all probability was Fiedler. The building on the bottom right of the image is the railway station.

Aerial photograph in picture postcard format showing Aus from above – 1915. The photographer in all probability was Fiedler. The shapes of military tents can clearly be seen.

4.2 Period between the two World Wars (1918 – 1939)

Following World War I, military commanders soon saw the potential advantage offered by up-to-date aerial imagery of the battlefield. Cameras were equipped on all makes of aircraft, and the wartime practice of aerial survey was born. Later advancements in aviation and photography meant flight crews could go further and return with more valuable images, reveal enemy movements and plan future attacks.

Military control of air surveys was inherited from the war. Still, after 1916 it gradually gave way to the involvement of South African commercial companies in that in the wake of World War I, several wartime pilots bought surplus military aircraft, setting up the first civil aviation enterprises in South Africa.

Aerial photography activity during this era can briefly be summarised as follows:

- Between 1919 and early 1922 the Solomon brothers, used their aircraft for commercial ventures. They also started taking oblique aerial photographs which, in all probability, became the first use of a winged craft in South Africa to capture photographs from the air in order to generate an income from them. Many of the images they captured were of well-known parts of the Cape peninsular. They also converted their photographs of individual farmhouses into postcards which they then sold to the farmers. This started a trend that later companies continued until at least the 1960s (Illsley, 2012)

- What is thought to be the first operational vertical aerial photographs taken in South Africa were those captured during the 1922 gold miner strike, which turned into a violent confrontation between miners and the government along the entire Witwatersrand. The South African Airforce (SAAF), which had barely assembled its first aircraft, was called into action. During the attack by army units to recapture Fordsburg square, an observer in a DH9 aircraft photographed the advance of tanks and troops. The resultant glass plate negatives still survive in the military archives in Pretoria (Illsley, 2012)

- Among other aerial photography projects undertaken in the 1920s were:

- 1925 Kalahari Irrigation Reconnaissance;

- 1926 Vaal-Harts irrigation scheme

- 1927 Transkei survey, and

- the 1929 survey of the route for the Belfast to Waterval Onder railway line

- the first use of aerial photography in plant-ecological survey was that of AOD Mogg in 1929 with his account of the flora in Pretoria in relation to its geology. He took hand-held oblique photographs from the side of an aircraft.

In tandem with the above, the SAAF under its founding father, Sir Pierre van Ryneveld, was in a position to undertake aerial photography from the very beginning because the requisite photographic equipment was included in the package of aircraft, spares and hangars donated by the British.

After the SAAF was established, it was decided in 1921 to photograph the entire South-African territory for surveying purposes, one of the first tasks conducted by the Air Force. On 26 April 1921, the first aerial photograph from a SAAF aircraft was recorded by the photographic section of the Air Force, then known as 67 Air School (van der Westhuizen, 1996).

In most cases, the tasks undertaken by the air force were limited to specific areas in the country. For mapping purposes, systematic aerial surveys were not in place at that point in time.

Not all SAAF aerial photography was of the vertical variety in that some oblique images were also captured from the rear cockpit of the biplanes to have a record of all airfields in the country and strategically essential facilities such as harbours.

The SAAF’s monopoly in aerial surveying was reduced because a private entity, Aircraft Operating Company (AOC), opened an office in Johannesburg in 1931, working for various government departments.

By 1936, the SAAF had established a resolute photographic and survey flight unit at the Zwartkop Air Base.

The first camera used by SAAF was a semi-automatic Williamson-made LB camera fitted with interchangeable magazines, each holding 18 photographic glass plates in special metal sheaths (van der Westhuizen, 1996).

In 1931, the fully automated F8 roll film camera was introduced, easing the photographer’s work considerably. One magazine held 100 exposures while recording all relevant information regarding a photographed area, such as exposure number, exposure time and altitude.

The F24 camera was introduced a year later (1932) and could record 125 images.

Trails with multi-lens cameras (seven lenses) found that the use thereof was not practical for the work intended.

Until 1938 the responsibility of positioning the aircraft during aerial surveys to obtain the necessary overlapping strips of photographs was left to the pilot, whose only aids were maps (where they were available), combined with his ability to memorise small ground details and judge accurately short ground distances from an altitude of between 8000 to 12 000 feet above ground level. Needless to say, this method was unsatisfactory and consequently, special camera-aiming sights were obtained. A third crew member, the photographic navigator was added to the survey crew, which until then, had consisted only of the pilot and the camera operator. The duty of the navigator was to direct the pilot along the flight lines predetermined by the surveyors (van der Westhuizen, 1996).

A Keystone Fairchild F8 Aerial camera that was in use during the Second World War – from the collection of Carol Hardijzer

An electrical Graflex camera used during the Second World War – from the collection of Carol Hardijzer

4.3 World War II (1939 – 1945)

From World War II onwards, aerial photo coverage and improvement in camera equipment expanded rapidly.

Aircraft used in aerial photography initially flew low, but the threat of being shot down required planes to fly higher, encouraging the development of cameras with longer focal lengths.

Just before the outbreak of World War II, the SAAF photographic section consisted of thirteen members who surveyed a large area within the Union from the air using aircraft such as Wapitis, Gloster Survey and Airspeed Envoys. Apart from flying duties, these photographers also had to assist with ground photography. The training of photographers changed drastically to accommodate the growing request for regular photographic tasks, such as aircraft accidents, modifications on aircraft, road accidents and other photographs used for archival purposes (van der Westhuizen, 1996).

With the outbreak of World War II in 1939, a conflict that South Africa joined as part of the British Commonwealth, the story of AOC and the SAAF's first operational photo reconnaissance unit became closely intertwined. The SAAF would go on to operate alongside Allied squadrons in North Africa and Italy, winning respect from British and American units for their work, including that of the two photo reconnaissance units (Illsley, 2012).

Bensusan (1966) provides rich information on aerial photography during World War II. What makes this information, captured below, even more significant is that he was there himself – as an aerial photographer. In his writing, he refers to himself on two occasions.

Bensusan (1966) suggests that during World War II that there were over five hundred trained photographers in the South African Air, Land and Naval forces.

In 1941, under the heading of the South African Air Force (SAAF), an advertisement appeared in the daily press for one hundred photographers “urgently required, men with experience preferred, but others will be accepted for training, pay attestation 5/- per day, plus usual allowance; on qualification increased from 7/- to 10/-. Rapid promotion for good men.”

This advertisement was constructed by the personal assistant to the Director of Photography of the SAAF, Major WD Corse (at Defence Headquarters in Pretoria). According to Bensusan (1966), this advertisement caused consternation at Headquarters in that nothing was known of its source. Especially considering that groups of aerial photographers were already under full training at Robert Heights (Pretoria).

Many of South Africa’s foremost professional photographers had answered the call. By the end of 1941, some seventy skilled aerial photographers and photographic instructors had completed their training in the combined RAF and SAAF programme.

In addition to practical work of up to one hundred hours flying time, the photographic course consisted of 12 weeks of theoretical training on technical aspects of general and aerial photography, repair and maintenance of aerial cameras and aerial survey in the production of mosaic maps.

67 Air School undertook general and aerial photography instruction at Zwartkops Airbase where they were responsible for all aerial survey work in South Africa during the War for mapping purposes. Some 210 000 square miles (544000 square kilometres) of the Union of South Africa was photographed between 1939 and 1945.

Besides other aircraft used by the SAAF at the time, a Gloucester aircraft was also in use, one of only two in the world built especially for aerial surveys.

Many of these trained photographers eventually saw action in the Abyssinian and Madagascan campaigns.

Amongst others, Bensusan (1966) shares the story of two SAAF “Battle” aircraft that were attacked over Kismayo on the coast of Italian Somaliland while they were taking photographs of shipping on 22 November 1939. The Commander-in-Chief of the East Indies had mandated the SAAF to furnish regular photographs of all shipping activities in these parts.

Bensusan (1966) also captured a fascinating narrative of this campaign, where Major RH Preller set out on a reconnaissance flight in the Kismayo area on 19 June 1940 with air corporal BR Ackerman and the photographer EH Petterson in the only Fairey Battle aircraft of No 11 Squadron. They stayed in the area for some time, taking photographs, especially of two enemy warships. When returning to base, an Italian bullet struck their engine and caused a leak in the cooling system, forcing them to land in the uninhabited dry bush country. After removing the magazine from the air camera, the compass, machine gun and other instruments, they burned the aircraft and set out on foot towards the border some sixty-two miles away. Following a camel track, the trio eventually discarded everything, except the precious air photographs. They eventually found a mud pool that saved them from dying of thirst. From there, Preller continued alone and reached base. The two corporals left behind were later rescued. The films survived the hazardous wanderings and later proved to be immensely valuable.

Resultant photographs taken at the time were not only used in military reconnaissance but also used in producing prints for survey companies and the compilations of maps.

Aerial photographers also received due recognition for their work during the war in that Corporal PC Sedwell, air gunner and photographer of SAAF’s No 11 Squadron, received the following citation:

Corporal Sedwell has displayed continuous gallantry and devotion to duty while photographing points of immense military and strategical value in Mogadishu area in August and September 1940

Aerial photographers sadly also experienced the wrath of the War in that photographer Hothersal was killed in action when shot down in East Africa during a survey flight. Later, photographer Nat Hawk was lost in the Western Desert while performing his duties as a photographer.

Throughout the Western desert in Egypt, Libya, Tripolitania and Tunisia, the Allied forces were supplied with endless aerial photographs taken by SAAF’s 60 Squadron on full-time reconnaissance duties.

South African photographers had played their part in the victory but there was no time for relaxation in that soon they had to move onto Malta, Sicily and then Italy. Here the SAAF’s No 60 Photographic Reconnaissance Squadron spent their first white Christmas with Air Sergeant Jack Arnold (formerly a professional photographer in the Eastern Cape) and Air Sergeant Karl Baumgartel as senior photographers, whilst Charles Barry, a noted amateur photographer back then, was their pilot. Ralph Hodgson was the photographic interpretation officer.

Nearby, at Foggia, was No 3 Wing SAAF comprising three squadrons. Their photographic interpretation officers were Captain EB White and later Lieutenant NJ Swardt. Flight Sergeant AD Bensusan and Sergeant Lotter were in charge of the huge photographic unit with some thirty-six photographers at one stage producing up to 3500 prints in one day. This photographic section of No 3 Wing SAAF received a special commendation for their photographs which resulted in the discovery of ammunition dumps in Italian cemeteries.

With heavy-bomber night raids over Europe, No 2 Wing SAAF came into operational flight with Liberator bombers. They carried timed aerial flash units that illuminated the countryside from thousands of feet up and produced the first operational night photographs for the SAAF. Here Captain QEW McGlasham was the photographic interpretation officer while Flight Sergeants Bensusan and Cliff Moller were in charge of the photographic work.

On 12 May 1943, No 21 Squadron dropped their last bombs on Africa, which was photographically recorded. The information captured on the photograph indicates that the image was captured at 03h26, at an altitude of eight thousand feet, using an 8-inch lens on an F24 aerial camera.

The unit was recalled from their overseas duties in 1945 whereafter they were temporarily disbanded, only for a restructured 60 Squadron to resurface again on 1 January 1948, responsible for all photographic survey and reconnaissance in South Africa. Four Dakotas for aerial survey and four spitfires for photographic reconnaissance training were allocated to the 60 Squadron.

Not only professional commercial photographers accepted the challenge to be trained as aerial photographers during the war. South African Railway (SAR) employees (from the publicity department and other railway departments) also assumed the challenge of becoming aerial photographers.

Another example of a professional photographer who joined the ranks of SAAF aerial photographers at the outbreak of war was Krugersdorp-based Robert Kassel. He had been practising as a photographer since 1905 and had presented the Duke of Windsor with an album of pictures of Krugersdorp during his visit in 1927.

Oblique aerial photograph of Pretoria (westerly direction), showing the bottom of the Union Building grounds, Church, Pretorius and Schoeman streets with the Caledonian grounds on top right hand. Photograph by Dotman Pretorius

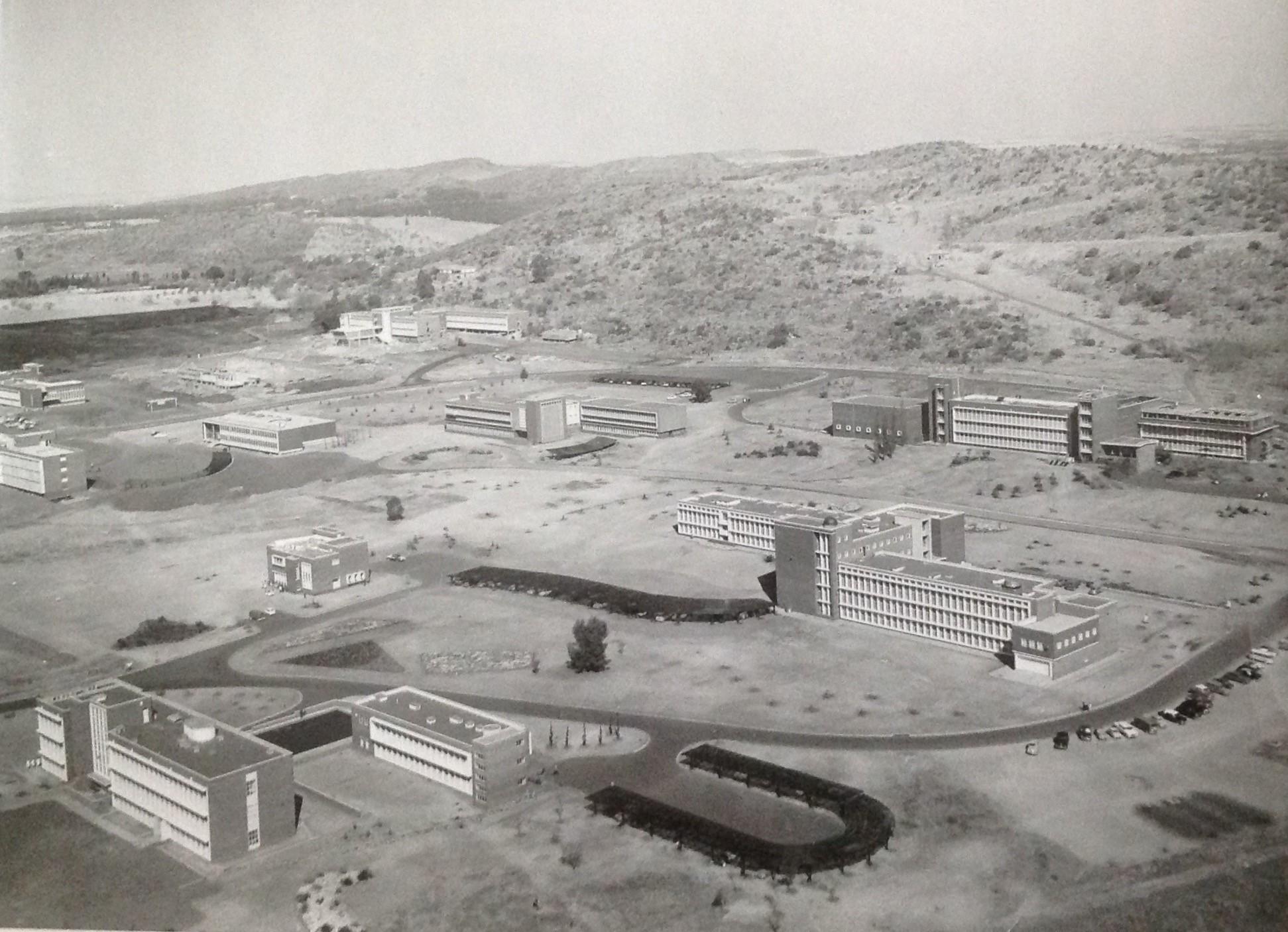

Oblique aerial photograph by Dotman Pretorius (1960s) looking in a South Easterly direction, showing the CSIR complex (established 1945)

Oblique aerial photograph by Dotman Pretorius (1960s) showing a rural Ndebele village just outside Pretoria. Note the cars parked in the shade of the tree bottom right.

While Bensusan (1966) names some photographers active during the war, it is also essential to highlight the work by Ireland-Low.

James Augustus Ireland-Low was born in Dunedin, New Zealand, on 17 November 1880. After completing a photography course at Farnborough, England, he came to South Africa during the Anglo-Boer War.

At the start of World War I, he enlisted with the Royal Flying Corps and served at 26 Squadron between 1914 and 1919. Although it has been suggested that he was a photographer during the German South-West African campaign, it is however not clear whether he took aerial photographs at that point.

Pierre van Ryneveld later recruited Ireland-Low in England for the South African Airforce, which he then joined on 1 April 1921. Less than a year later Ireland-Low transferred to the No 1 Squadron at the Zwartkop Airforce base.

It is recorded that he was the Chief Air photographer of the SAAF in 1923.

In 1947, Ireland-Low, then commanding officer of the “photographic school”, was presented with the M.B.E. by King George VI during the Royal tour of South Africa.

In a Railway magazine article, Ireland-Low’s activity as a photographer has also been described as follows:

After a long break, Durban residents have again become accustomed to the drone of planes cruising over the town. Two De Haviland machines of 300hp made continuous trips, remaining aloft for a couple of hours at a stretch and it transpires the airmen were engaged in connection with the model of this town which is being arranged for in connection with the British Empire Exhibition. Sergr-Major Ireland-Law (sic), Chief Air Photographer of the SA Aviation Corps, exposed some 250 plates during 12 trips…. It is understood that the whole of the photographs will be fitted into a complete panoramic picture.

It has been suggested that Ireland-Low was the first photographer attached to the SAAF to have compiled a portfolio of his work. These photographs he captured by using a hand-held camera. This portfolio has not been seen by me at the time of publishing this article.

So significant was his contribution in South Africa that a street in Valhalla (Pretoria) was named after him. On 1 June 1926, he married Clara Nancy Hands at Robert Heights, 24 years his junior. He passed away in Pretoria on 14 September 1960.

Another name that surfaces is that of Restall, who saw service in East Africa and Abyssinia. He eventually became a photographic officer at Zwartkops with the rank of Captain.

4.4 Period post World War II (1945 – the 1970s)

This period saw rapid technological expansion in air-photo interpretations. Mapping in the South African military also has advanced from hand-produced maps to the use of complex equipment that satisfies the sophisticated mapping needs of a modern defence force.

By 1950 the entire country had been covered with aerial photography. The imagery was captured at a photo scale of 1:30 000 and flown at a height of approximately 4570m above ground level. In the 1960s, a super wide-angle camera was used, enabling the photography to capture smaller scales without losing accuracy. This meant each photograph covered a larger area, therefore fewer photos were required, and production time decreased.

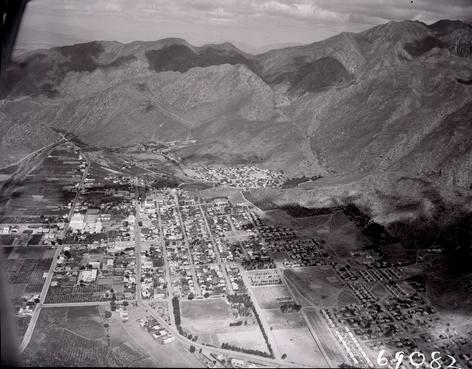

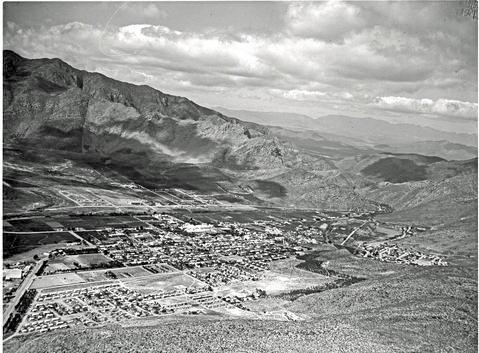

Oblique aerial photograph showing Montagu during 1960. Photograph by unknown photographer employed by the South African Railway Publicity department. Image via Drisa.

Oblique aerial photograph showing Montagu during 1960. Photograph by unknown photographer employed by the South African Railway Publicity department. Image via Drisa.

Oblique aerial photograph showing the Henneman floods. Photograph by unknown photographer employed by the South African Railway Publicity department. Image via Drisa.

Oblique aerial photograph showing Uitenhage. Photograph by unknown photographer employed by the South African Railway Publicity department. Image via Drisa

In 1970, the government decided that ultra-small-scale photography at a scale of 1: 150 000 would be used to re-map the contours and adjust for the change to the metric system.

The National Geo-spatial Information (NGI) is the government component responsible for aerial photography and national mapping. NGI continued to capture analogue photography throughout the country every 4-7 years until 2008 when it was decided to upgrade to a digital sensor system.

The SAR publicity department was also actively involved in taking aerial photographs. Some of their aerial photographs are included in this article. Also see Drisa.co.za for additional aerial photographs linked to the SAR Publicity department.

During this period, commercialisation of aerial photographs became even more evident in that photographers and journalists alike took to the air. It is photographs from this era that have become visually more appealing, also explaining why the bulk of images included in this article originate from this period.

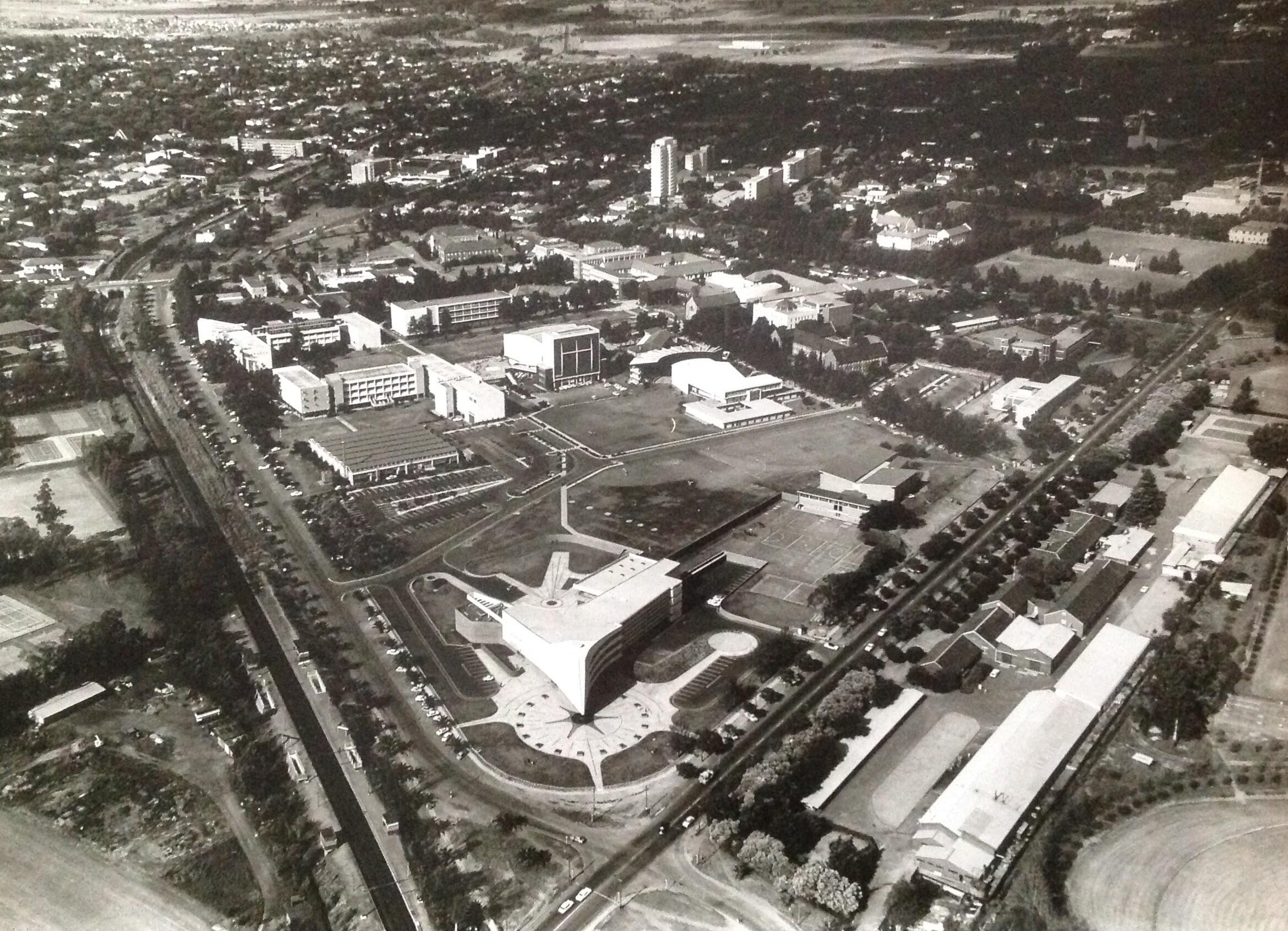

This article includes examples of two photographers from this era who saw the commercial value in capturing photographs from the air.

One of them is the Pretoria-based photographer Dotman Pretorius, who captured a vast number of aerial photographs of Pretoria, which today are of immense historical value. It is unclear whether these photographs were captured as part of an assignment or whether Pretorius saw this as an artistic opportunity to capture Pretoria from the air.

Another example would be Port Elizabeth-based J. Forbes, who had a photographic studio specialising in press, commercial and industrial photography.

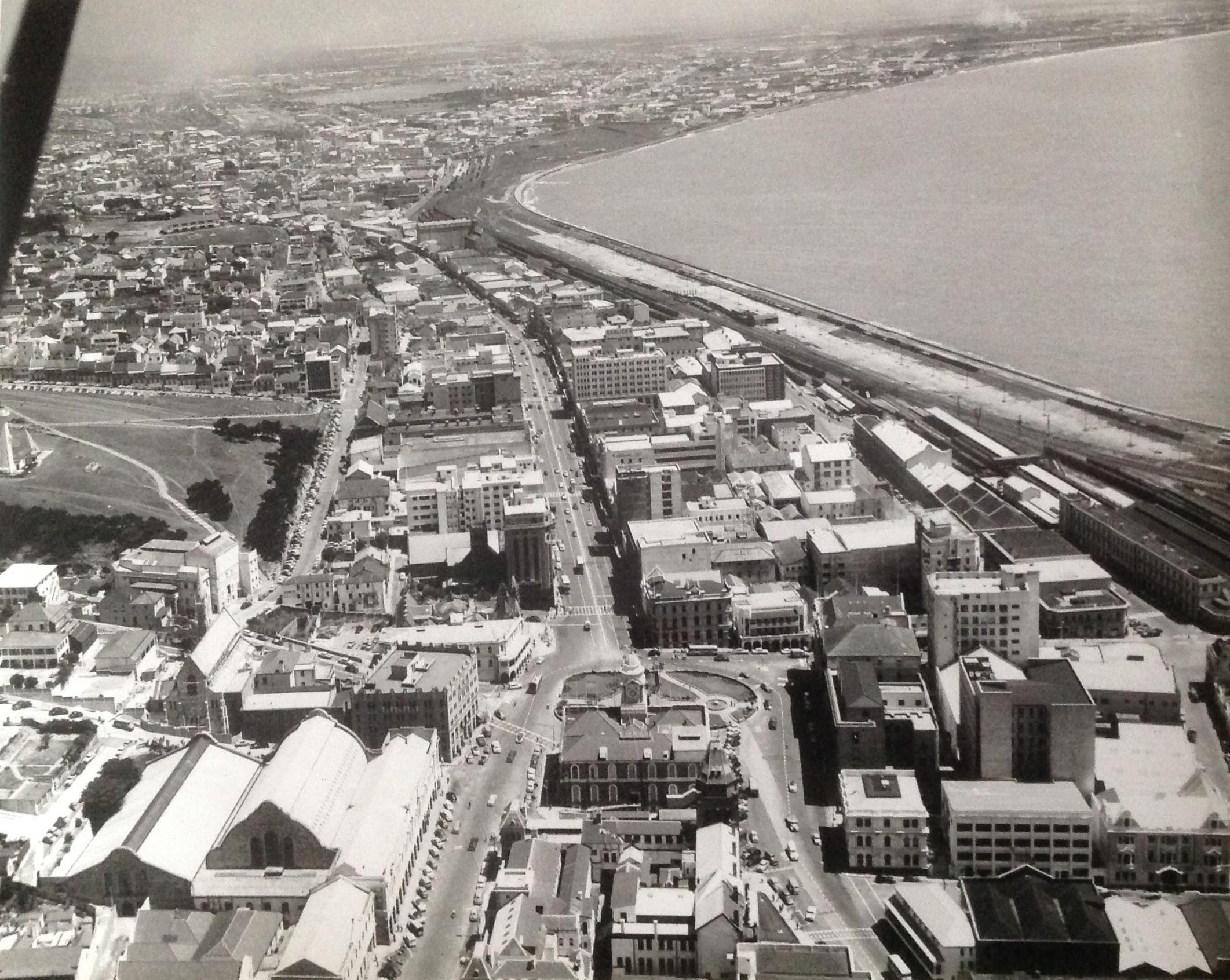

Oblique aerial photograph by J. Forbes showing early Port Elizabeth below. Forbes advertised his photographic business as specialising in Press, Commercial and Industrial photography.

Oblique aerial photograph by J. Forbes showing early Port Elizabeth below (1970s). With the help of images such as these, town development and changes can be recorded.

Oblique aerial photograph by J. Forbes showing early Port Elizabeth below (1970s). Images such as these, assist in amongst other, town planning.

Oblique aerial photograph by J. Forbes showing early Port Elizabeth below (1970s). The railway infrastructure is clearly visible at the bottom right of the photograph. Also, visible next to the railway station is the historical landmark, the 50-meter-high Campanile which was completed during 1922.

Oblique aerial photograph by J. Forbes showing early Port Elizabeth below (1970s). The Donkin Reserve, Pyramid and lighthouse can be seen at the top centre of the photograph.

Contemporary images such as these have become attractive to citizens who can relate to earlier photographs of, amongst others, their towns, neighbourhoods, schools or universities as portrayed on the images. For example, I recently placed an aerial photograph by Pretorius of early Pretoria University on Facebook (Old/Ou Pretoria). This image received much traction due to sentimental association from university alma maters.

Towards the end of the 1960s, aerial photographers were also involved in the Bush War (Namibia).

Closing

While unlikely, the remote possibility exists that there may have been other unrecorded events between 1899 and 1911 in South Africa during which aerial photographs have been captured.

Even given the historical synopsis of aerial photographic above, the crucial question about early South African aerial photography remains.

Initial South African aerial photographs were all captured by foreign nationals whilst on South African soil. Who was the first South African citizen to have captured an aerial photograph? While not South African born, was this Ireland-Low after all or may this have occurred earlier at Durban during 1911?

Ongoing research may assist in clearly answering the question above.

Van der Westhuizen (1996) states in a short article he compiled on the history of photography in the South African Airforce that he relied on an unpublished 400-page document from the early 1980s. This document originates from the research conducted by 7 photographers attached to the Central Photo Technical Establishment (CPE) unit based at the Airforce base in Waterkloof.

Personally, I have not had sight of this document at the time of publishing this article. Should this document surface, the content thereof will certainly supplement this article. It may also be a worthwhile consideration to rework (if necessary) and find a sponsor to publish this all-important work.

Oblique aerial photograph by unknown photographer of Cape Town, showing Table Mountain and wider Peninsula (Circa 1960).

Aerial picture postcard (1970s) of Johannesburg

Aerial picture postcard (1970s) showing Bantry Bay with Sea Point in the background.

Special Acknowledgement - On a visit to the South African Airway Museum library, based at the Rand Airport, volunteer aviation historian Herman Bosman showed me the photographs curated by the museum and provided me with a copy of Ad Astra photographic magazine in which the article by Marius van der Westhuizen appeared.

About the author: Carol is passionate about South African Photographica – anything and everything to do with the history of photography. He not only collects anything relating to photography, but also extensively conducts research in this field. He has published a variety of articles on this topic and assisted a publisher and fellow researchers in the field. Of particular interest to Carol are historical South African photographs. He is conducting research on South African based photographers from before 1910. Carol has one of the largest private photographic collections in South Africa.

Sources

- Bensusan, A.D. (1966). Silver Images. History of Photography in South Africa. Howard Timmins: Cape Town

- Cormack, A. (1990). NO. 1 Balloon section, Royal Engineers, In the Boer War. Journal of the Society for Army Historical Research, 68(276), 253–261 (www.jstor.org/stable/44227207 & 44225632)

- Hardijzer. C.H. (2023). Unacclaimed South African Railway photographers (1894 – 1940) (thehertigeportal.co.za)

- Harold, A. (1983). Camera above the clouds – The aviation photographs of Charles E Brown. Airlife Publishing. Shrewsbury. England

- Illsley, J.W. (2003). In Southern Skies – A pictorial history of early aviation in Southern Africa (1816 – 1940). Jonathan Ball Publishers. Jeppestown

- Illsley, J. W. (2012). Seeing our land from Above: The first decades. (www.ee.co.za/wp-content)

- Jacobs, A. & Smit, H. (2004). Topographic mapping support in the South African military during the 20th century. Scientia Militaria: South African Journal of Military studies. (www.ajol.info/index.php/smsajms/article)

- L’Ange, G. (1991). Urgent Imperial Services. South African Forces in German South West Africa (1914-1915). Ashanti Publishing. Rivonia: Johannesburg

- Lee, E. (1986). To the bitter end. A photographic history of the Boer War 1899-1902. Penguin Books: Middlesex, England

- Nesbit, R.C. (1996). Eyes of the RAF – A history of photo-reconnaissance. Sutton Publishing Limited. Great Britain

- Rizzo, L. (2019). Photography and History in Colonial Souther Africa: Shades of Empire. Wits University Press. Johannesburg

- Smith, K. (2009) The Australian Boer war memorial – Aircraft in the Boer war. (www.bwm.org.au/aircraft.php)

- Swiss National Archives (extracted one 1911 Spelterini photograph from picryl.com/media)

- Unknown. (2020). Transportation history: “Boston as the eagle and the wild goose see it”: A Milestone in aerial photography. (transportationhistory.org - extracted 17 January 2023)

- Unknown (extracted February 2023). Aerial photography 1926 – 2008. What we do. South Africa: Department of agriculture, land reform and rural development (ngi.dalrrd.gov.za)

- Van der Westhuizen, M. (1996). The unique history of SAAF. Ad Astra – Photo Edition. SA Navy Publication Unit. Simonstown

- Webpage - Digital Railway Images South Africa (Drisaco.za). All images by South African Railway publicity department extracted from this webpage

- Webpage – Goodfreephotos. One 1911 Spelterini photograph extracted from goodfreephotos.com

- Waxman, O.B (2018). Aerial Photography’s Surprising Role in History. (time.com/longform/aerial-photography)

- Wikipedia.org. Aerial photography (extracted 17 January 2023)

- Wikipedia.org. Aviation photography (extracted 15 February 2023)

- Wilson, H.W. (1900). With the Flag to Pretoria – A history of the Boer War of 1899-1900. Harmsworth Bothers. London

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.