Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

The Cape Government Railway (CGR) from Cape Town was opened to Matjesfontein (192 miles 66 chains. Altitude 2966 feet) on 1 February 1878. From Matjiesfontein [today’s spelling] the alignment followed the course of the Bobbejaan River eastwards. The next passing loop was Whitehill (199 miles 27 chains. Altitude 2715 feet).

The logical route for the extension northwards from Whitehill, was adjacent to the course of the river. However, about 5 kms east of Whitehill, the Bobbejaan River shaped like an inverted and elongated “S” cuts a deep poort through the north - south Mostertshoek ridge. [This poort is known as Rietfonteinpoort.] This terrain would have necessitated two costly bridges each of two to three spans. In addition to the difficult terrain of the poort, the situation was complicated by Dwyka tillite inclusions in the dolerite sill. These geological features would have demanded extensive blasting.

Consequently about 3 kms north of Whitehill the alignment swung south-east away from the dry river course to cross the Mostertshoek ridge about 3 kms south of Rietfonteinpoort. This route over the ridge involved shallow cut-and-fill construction on the southern side. Deeper cuttings were necessary on the northern side. However, the rock in this area was relatively soft being Dwyka mudshale. A passing loop was built where the alignment crested the ridge. It was named Mostertshoek (203 miles 18 chains. Altitude 2722 feet). From Mostertshoek the alignment followed the course of a twisting spruit to the north-east. The alignment, with 1:40 and 1:60 embankments and cuttings, dropped to the next passing loop at Baviaans (208 miles 10 chains. Altitude 2397 feet). The steep Baviaans – Mostertshoek section often necessitated double-headed Up working. [Up trains ran from north to south. All train workings had a number.] (In 1953 Baviaans was changed to Baviaan.)

This area of the southern Great Karoo is an inhospitable, treeless, wind-blown expanse of barren rocky ridges with a sparse covering of bushes. Farm homesteads are few and far apart. For railway employees at the isolated stations it was a deserted and desolate land. Each station had a foreman whose tasks were inter alia to operate the telegraph for communication, accept trains into and despatch trains from the station, to operate the points and to give flag signals accordingly.

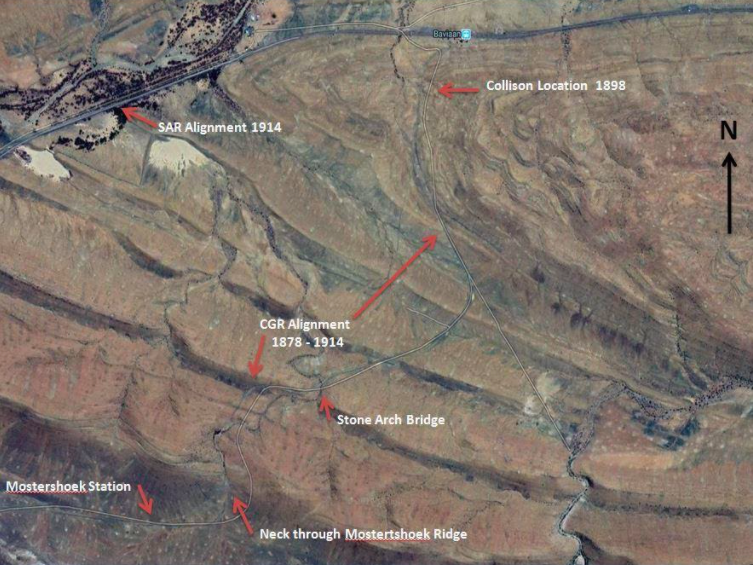

CGR alignment: north-east side of Mostertshoek Ridge

On the night of Tuesday 16 August 1898 goods train 48 Up “instead of being brought up to the level crossing place” at Mostertshoek station, was halted short of the loop points at the northern end of the station. The goods train “was allowed to stand on a falling gradient,* while the engine was uncoupled to take on a couple of trucks.” [CGR General Manager’s (GM) Annual Report 1898.] [*1: 68 and 1: 41] The goods train should have been hauled on to and stopped on the loop line at the level station and made safe before the truck was shunted into the train. [Railway archaeology confirms that there was a short siding, running north-west, off the loop line. From time to time a truck was shunted into the siding for the loading of bricks.]

The site of Mostertshoek station. Train 48 Up stopped about 30m beyond the location of the electricity pylon. The CGR track ran through the neck in the ridge on the left.

Train 48 Up consisted of locomotive No. 157 and 13 trucks of which one was a box truck with 34 native passengers. On the locomotive footplate were driver Simpson and fireman Hoolighan. The guard was Marsh.

After the goods train stopped and before the locomotive was uncoupled, the guard would have made the train safe by ensuring that the chain-brake in the guards-van at the rear was tightly on and by ensuring that the brake-levers on the trucks were pinned down in the On position.

From the report of The Chief Traffic Manager, Mr Price, it can be deducted that this goods train was not vacuum-braked. The vacuum brake permits the train driver to apply the brakes simultaneously on all the trucks or coaches in a train. Safety instructions for a train without vacuum brakes, would have the guard pin down the brake-lever of each truck manually before uncoupling the locomotive. The act of manual brake application would have involved the guard walking the length of the train and physically pinning down the brake-lever on each truck. Something which he could do while walking from the rear of the train to the locomotive to converse with the driver.

With the trucks standing on a falling gradient, it was essential that the guard met all the safety requirements. From the GM’s report it appears that all or some of the safety requirements were not met. “This serious accident would have been avoided by the exercise of ordinary care.”

Why did the guard decide - per CGR Rule No 284 he was in charge of the shunt - and the driver and the station foreman acquiesce, to stage the train outside the loop line for the shunt? Firstly this was probably not abnormal and secondly there was a time constraint. The train following 48 Up was 4 Up – the fast mail/passenger train. CGR Rule No 352 demanded that the mail train should not be unduly delayed.

The safer option would have been to pull into the loop line and wait there for the Up Mail train to pass on the main line. [CGR Rule No 352 also stipulated that a Mail Train passed through a station on the main line.] Instead of pulling into the loop line at the station, they stopped, on a falling gradient, short of the points at the northern end of the station and uncoupled the locomotive.

The most probable explanation for what happened after the locomotive was uncoupled from the goods train is that the guard failed to tighten the chain-brake in the guards-van and/or failed to pin down sufficient brake-levers to hold the train or the chain of the chain-brake broke and there were insufficient brake-levers pinned down to negate the consequences of a break of the chain. Whatever the reason(s) the trucks started to roll down the decline.

Imagine the horror-stricken and desperate train crew’s disbelief as the trucks gathered momentum. The guard grabbed hold of a truck-side and tried to pin down another brake-lever. After a short distance the guard was thrown off by the velocity of the run-away trucks. The driver put his engine in reverse and set off after the runaway trucks blowing the engine’s whistle continuously in warning.

Two gangers living in Cottage 42 saw the passing runaway trucks. They observed sparks flying from the wheels. [This indicated that the brakes were partially effective.] The run-away trucks charged ever faster down the decline towards Baviaans station from which the double-headed 4 Up mail train with much smoke and steam had already departed.

Imagine the terror and panic of the 37 native passengers in the box truck as they realised that they were hurtling through the darkness ever faster down the ridge. They might have seen the light from the headlamp of the front locomotive and the lightened coaches of the mail train rapidly coming ever closer. Then with a violent and devastating force the run-away trucks collided with the locomotives. The accident occurred about 18:20.

From this location goods train 48 Up started its runaway down the decline. The neck through the Mostertshoek Ridge is left behind the pylon.

Map of sites associated with the accident

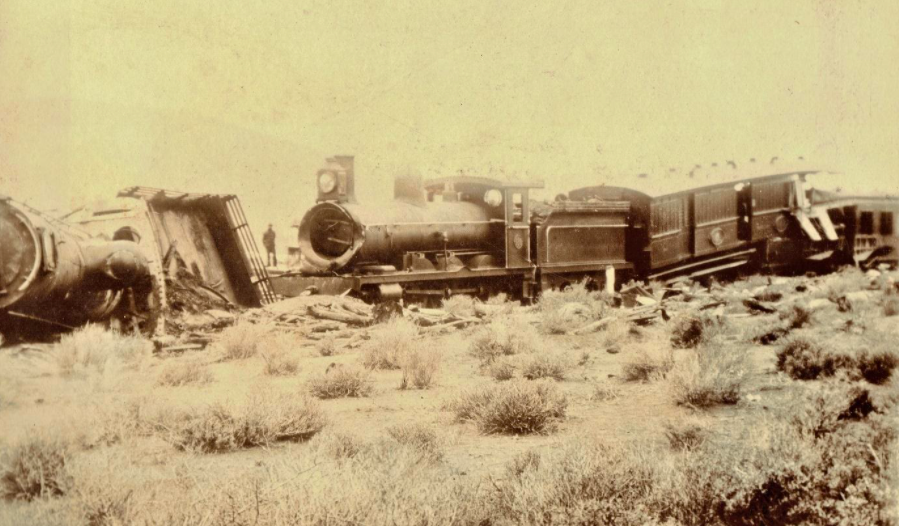

CGR Class 6 locomotive and passenger train: 1897 [Cape Archives DRJ 410]

Mr Beatty, the Chief of the CGR Locomotive Department, who was in 4 Up telegraphed later from Matjiesfontein: “I was a passenger in the 4 Up. The train consisted of two engines and seven bogie vehicles [coaches]. About six miles south of Laingsburg* we came into collision with a runaway portion of the 48 Up train which was travelling at a high rate of speed.”

* The GM’s 1898 Report gives the location of the accident as 206½ miles from Cape Town.

Collision location: CGR alignment 206 miles 39 chains [1 Mile = 80 Chains]

The leading engine of 4 Up mounted the trucks. The second engine and train kept the rails with the exception of the leading bogie wheels. The newly built Travelling Post Office (TPO) van behind the second engine, telescoped into the second coach which was a “Netherlands coach*, the first three compartments of which were completely wrecked”.

[*Indicates the coach was owned by the Nederlandsche Zuid-Afrikaansche Spoorweg Maatschappij (Netherlands South African Railway Company)] which operated in the Transvaal Republic prior to the British seizure of the republic’s railways during the Boer War in 1900.]

The wooden box truck with the native passengers shattered on impact. Coals from the fire-box of the derailed first locomotive caused a blaze which rapidly engulfed the remains of the box truck. The GM reported that 27 of these passengers were killed. All the trucks of 48 Up were wrecked.

Two Post Office officials were badly injured while a third who was asleep in the rear portion of the TPO van, escaped with a few cuts.

In the two coaches behind the TPO, five adults and one child were killed. They were the Rev and Mrs du Toit and their little girl who lived in Dewetsdorp; Messrs. de Villiers, Cope and Tait of Johannesburg.

The three men were described as footballers. Mr Rees of East London was badly injured. Another child (a male) of this du Toit family survived with slight injuries. Mr Cope had travelled second class to De Aar, but there he upgraded to first class to travel with Mr Tait. All the fatalities were in the first class coach (behind the TPO) and the third coach. Mr de Villiers and his son were in the third coach. While the father died, the son was “practically uninjured”. He was a student at the SA College, Cape Town. Passengers in other coaches “escaped with nothing worse than a severe shaking.”

The Cape Times newspaper reported that driver, Burgon,* of the front engine, suffered several broken ribs. The fireman, Brooks, of the front engine was cut about the face, but his injuries were not serious. The driver and fireman of the second engine were not injured.

* In this report incorrectly given as O’Brien.

Three doctors [Dr Young – a passenger on 4 Up – Drs Robertson and Lefevre] attended the injured “stitching cuts and putting broken limbs into splints”. [Dr Robertson was from Matjiesfontein. Dr Lefevre was the RMO at Touws River.]

The passengers of 4 Up were transferred at about 02:00 under the supervision of Trains Inspector Feuther and Traffic Inspector Johnson. The injured passengers – with Dr Lefevre in attendance - were conveyed to Touws River. Inspector Nettle of Touws River arrived at the location of the accident and started the construction of a deviation round the wrecked portion of the train. The deviation was in operation about 09:00. This enabled passenger trains 6 Up and the 3 Down to proceed.

A magistrate [presumably from Touws River] arrived at the scene of the accident at 06:30 and made arrangements for the transfer of the dead to Matjiesfontein.

Owing to the accident the mail did not arrive before the scheduled departure of the mail ship from Cape Town to England. Consequently the ship’s departure was delayed until the arrival of the mail bags from 4 Up the following afternoon.

This was the worst accident, in terms of lives lost, in the CGR's twenty year history. Mr Price, the CGR’s Chief Traffic Manager wrote: "This serious accident would have been avoided by the exercise of ordinary care; nor is the feeling of anxiety lessened by the circumstances that most of the serious accidents to passenger trains of recent years have occurred in one section of the Cape Railway system."

The CGR’s General Manager wrote: "I am glad to say that the arrangement which I authorised some years ago for attaching the automatic brake to all carriages and rolling stock were sufficiently far advanced to enable the automatic brake to be applied to all trains within a few days after the accident so that no further apprehension may be entertained with regard to the safety of the trains arising from a similar cause. The reports I have received from the Chief Locomotive Superintendent with regard to the efficiency of the brake are highly satisfactory." [Automatic brake and vacuum brake are synonymous.]

Clearly there had been delays in the fitting of vacuum brakes to all carriages and rolling-stock. The General Manager’s statement appears to be an attempt to keep blame and liability from his office.

The Mostertshoek accident on 16 August 1898 was the worst accident the Cape Government Railway (CGR) had experienced. “This year’s working has been marred as well as saddened by an accident... involving a more serious loss of valuable lives than any which had previously occurred,” wrote the CGR General Manager (GM) in his 1898 annual report. It was CGR policy that “in all cases of serious accident”, a magistrate or some other suitable person – assisted by railway experts - was appointed to investigate the accident.

In terms of CGR policy a “very careful and searching departmental inquiry was made into all the circumstances” of the collision. This inquiry was “in addition to the public inquest held by the Resident Magistrate of Worcester and the special investigation made on behalf of the Government by the Resident Magistrate of Cape Town.”

C B Elliott the CGR GM requested W M Fleischer, Cape Town’s Resident Magistrate, to make an impartial investigation “into the whole circumstances of the case.” Eight days after the accident [24.08.1898] Fleischer made an on-site inspection with Beatty [the CGR’s Chief Locomotive Superintendent] and Difford [the CGR’s Traffic Manager of the Western System]. They took evidence at Matjiesfontein on 25-26.08.1898. On the latter day “a train ... comprising the same [locomotive] class and number of trucks and loads as were attached to No 48 Up” was used to examine “the holding power of the brakes” on the section north-east of Mostertshoek.

Fleischer found: that the guard, Marsh, erred in not entering the level loop line and that he was guilty of “not properly or sufficiently applying the brakes necessary to prevent” the trucks running away that the Mostertshoek station Foreman, Milner, should have instructed Marsh to enter the level loop line and should have ascertained that the brakes had been properly applied. That the driver, Simpson, failed to follow Rule 225 [Shunting on Gradients] and Rule 306 [Dividing a Train on a Gradient].

After the inquiry the Resident Magistrate of Worcester was instructed to proceed against the guard on “a charge of culpable homicide”. The magistrate’s papers were referred to the Attorney-General who declined to prosecute.

The CGR GM wrote in his 1898 report that he believed “that the railway employés [Victorian spelling] were not guilty of wilful negligence, and that, although they had not fully complied with the regulations, they believed that the steps they had taken secured the train from running back.”

There this chapter in the history of the CGR ends though it did have further impact in terms of compensation paid in the event of a railway accident. How much compensation should be paid, required attention as the GM wrote in his 1898 report: “it is necessary to provide legislative provision for the maximum sum payable in case of accident... as recommended in my Annual Report for 1895.”

With the formation of the Union of South Africa in 1910, the CGR was incorporated into the South African Railways (SAR). With the legislative capital in Cape Town and the executive capital in Pretoria, the efficient operation of passenger trains through the Karoo was crucial to the country’s governance. In addition the increasing generation of electricity in urban areas - utilising coal-fired boilers - demanded the railway’s capacity of coal transportation be expanded. Consequently the SAR was pressurised into faster and heavier traffic. This resulted in sections of the CGR alignment being deviated with easier gradients. Between Matjiesfontein and Baviaan the grade was eased to 1 in 66 and the curves flattened to a minimum radius of 302 metres.

The Whitehill – Baviaan deviation was constructed in 1914. In the 36 years since the construction of the CGR route, there had been much development in the use of explosives and the use of concrete. The SAR deviation followed the Bobbejaan River northwards through Rietfonteinpoort. Two concrete arch bridges and extensive cuttings were required. [A fine specimen of a fossilized fish was found in sandstone during the excavations.] Over 1 100 labourers were employed on the construction. Water for masonry, drinking and washing was railed from Matjiesfontein and then transported by mule carts to the various camps. The SAR deviation is 1 mile 44 chains (2494 m) shorter than the CGR alignment. The engineer responsible for the survey and the construction of the deviation was J F Bateman. On completion the track of the 1878 alignment was lifted and trains over the Mostertshoek ridge and the railway disaster of 1898 disappeared into the mists of time.

1914 Deviation: bridge through Rietfonteinpoort on the Bobbejaan River

Thanks to the rocky semi-desert terrain of the area, the 1878 alignment is much as it was when the rails and sleepers were lifted. With the permission of the land-owner and with a high clearance vehicle, one can drive the alignment to the neck. This includes crossing a magnificent stone arched bridge.

CGR alignment looking west to the neck through the Mostertshoek ridge.

CGR stone arch bridge probably built by Scottish stone masons.

Sources

- Cape Government Railway: General Manager’s Report 1898 (Cape Archives)

- Magistrate Fleischer’s “Reports and Evidence in connection with the inquiry into the Railway Accident at Mostert’s Hoek Siding on 16th August 1898.”

- Grocott’s Mail (Cory Library, Rhodes University, Grahamstown.)

- Cape Times (National Library, Cape Town)

- George & Knysna Herald (Museum Archives, George)

- SA Railways & Harbours Magazine August 1914

- There is a reference in Spaanders wat Vlieg by L J Conradie 1952

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.