Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

Thomas Stewart was born in Craigend, Perthshire, Scotland, in 1857 and as a sixteen year-old entered into a pupillage with Mr D.H. Halkett, who on completion of his time after three years appointed him as an assistant. He then worked with the Glasgow Corporation Water Works and furthered his studies at Glasgow University. Later he joined the staff of Sir John Wolfe Barry before being recruited to South Africa in 1882. He arrived at the Cape on 28th of December in the company of another young Scot, James Rawbone.

Portrait of Thomas Stewart

The two young immigrants were less than charmed by their first impressions of Cape Town, which was windy, dusty and badly drained. As they explored the dimly lit St Georges Street they were annoyed by the stoeps of buildings which projected across the sidewalk and which ended abruptly and steeply at street corners. Hogmanay was to be a dreary time for the two spirited young Scotsmen. They vowed there and then that, if at all possible, they would return to their homeland on the next ship.

But it wasn't possible, as they had contracts to honour. Rawbone would make his mark in the Colonial Forestry service, and become the founder of the well-known Rawbone-Viljoen family, the apple-growing pioneers of Elgin. Stewart was employed as assistant to the Hydraulic Engineer of the Colony, Mr John Gamble.

John Gamble

Stewart reported for work on January 1st 1883 and found that the programme for the first day of the year consisted of an official picnic on Table Mountain. The party for this event included well-known politicians such as John X. Merriman (a land-surveyor by profession). The Chief Engineer duly read the rain gauges as part of the official duties. There were other practical sides to visit as Stewart was introduced to some dam sites which Gamble had identified as potential new sources of water for the growing city.

Though the Hydraulic Engineer was not officially responsible for Cape Town's water supply, his services were placed at the disposal of the municipality to find out why the Molteno Reservoir had burst the previous year, leaving Cape Town with a severe water shortage. One of young Stewart's first tasks was to crawl through pipes in order to find some reason for the failure. It was a vivid and uncomfortable introduction to his new job. (Presumably his efforts led to a solution of the problem, since the reconstructed Molteno Reservoir is still in service.)

Soon however his duties took him further afield. He was sent to assess the potential of the Olifants River at Clanwilliam for irrigation, and he looked at the possibility of irrigating the Harts River valley with water from the Vaal - both schemes were to be implemented some years later. He worked out schemes for water supply to Barkly West, Cradock, Burgersdorp and Aliwal North, and he made a favourable impression not only on his boss but also on some of the clients. Gamble was prepared to leave him in charge for a six-month period when he took home leave, and in his chief's absence he gave some telling evidence to the commission of enquiry into the Sanitary State of Cape Town. It was quite an achievement for a youngster still less than 30 years old. His contract was extended by six months, at the end of which he returned to Scotland.

But his initial opinions of South Africa had been replaced by more favourable impressions. Before the end of the year he was back in South Africa, with a commission from Cradock Municipality to construct the scheme he had designed. The supply was brought from a spring some 10 km away, and would continue to serve the town for many years. He spent two years in the Karroo, and then transferred his interests to Wynberg, which needed to augment its water supplies from the Orange Kloof area of Table Mountain. Having successfully built a reservoir near Constantia Nek and located sites for further reservoirs, he felt it was time to invite further commissions and in 1892 he set up on his own in St Georges Chambers, Cape Town as a consulting engineer.

Almost immediately he was commissioned to design and arrange for the building of the Woodhead Reservoir on the top of Table Mountain. At the same time he had been appointed by the tiny Kalk Bay and Muizenberg Municipality to sort out their water problems, which were solved by his design for the Silvermine Reservoir which was built by a contractor, G.S. Firth in 1898.

Woodhead Resevoir from above

Woodhead Resevoir Spillway

Not all jobs were productive. In 1898 the Colonial Government appointed him as technical member of the commission investigating an ambitious irrigation scheme at Steynsburg. The scheme was condemned. (Seventy years later the tunnel of the Orange-Fish scheme would emerge near Steynsburg and again bring water to the region.)

During the Boer War he was attached to the Royal Engineers as a major (without pay) and he designed defence works.

On completion of the war he returned to Scotland again, but not to stay - to claim a bride, Miss Mary Mackintosh Young, whom he brought back to Cape Town. She bore him three sons, but sadly passed away in 1921. He later married the widow of the well-known Rhodesian pioneer "Matabele" Thompson.

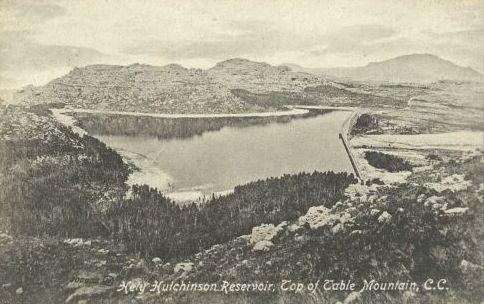

The Woodhead Reservoir did not solve Cape Town's water problems, and he gathered the survivors of his previous work force and began work on the Hely-Hutchinson Reservoir above the Woodhead. The Alexandra, Victoria, and De Villiers dams which served Wynberg were built in the same period - but this time the newly married young engineer lived at ground level and travelled up the mountain when required.

Old postcard of Hely Hutchinson Resevoir

Woodhead cableway

Another dam, to serve Simon's Town, was also on the cards. This one would eventually be engulfed by the Lewis Gay dam designed by Ninham Shand in the 1960's, during which the amazed engineers came across a fascinating piece of machinery, devised by Stewart. The chemical dosing system consisted of a float-actuated bicycle gear, complete with chain and pedals. The alum-dosed water then ran through a long trough containing lumps of limestone. From the trough the water was led in to the slow sand filters containing sea sand which had a large proportion of readily soluble seashell in it. The results were phenomenal. Never had a clearer, more sparkling, but still soft and palatable water been produced by this ingenious contrivance, and the Shand men were all grieved to have to see it make way for the essential larger plant of greater capacity.

The first years of the century became the busiest period in Stewart's life. Apart from the dams under construction, less well-endowed municipalities such as Rondebosch and Woodstock were looking to locate water sources in the Hottentots-Holland mountains. Stewart tramped the catchments and the valleys and made extensive surveys, and discovered two excellent sites in the Steenbras and Wemmershoek Rivers, which would see development in later years. For the time being however the little authorities did not have the financial resources to implement the schemes and nothing could be done until thirst caused the amalgamation of the seven minnows to form the consolidated Cape Town City Council in 1913.

Wynberg however was self-sufficient in water because of Stewart's mountain reservoirs, and could not only afford to thumb its nose at the merger, but to embark on an ambitious sewerage scheme. Cape Town had recently completed a successful scheme based on a sea-outfall, but Wynberg, with no coastline, had to go for a totally new concept for South Africa - a land based treatment works. And who else to design it but their tried and trusted consultant, Tom Stewart!

Despite not having worked in this sphere before, he produced a scheme which the Council preferred to those of the experienced overseas experts, Dunscombe and Pritchard. The treatment works was located in the area between Grassy Park and Prince George Drive (which was still to be built), more or less where the Klip Road cemetery now stands. It was claimed in an engineering publication of the day that there was now "a prospect of the sewage farm being rendered unnecessary; or at any rate will be greatly reduced in size, while sludge, the bete-noir of all precipitation works will cease to exist." Stewart, the prudent professional, merely reported these claims without undue comment, but the Town Clerk, Mr J.B. Munnik was more forthcoming: "Under this system there will be no smell or any unpleasantness… It is just like standing on a tank of ordinary water." In 1903 Wynberg Municipality became the proud owners and operators of the first municipal sewage treatment works in South Africa.

The Town Clerk was however disappointed in his expectations. The works did smell, and the site proved totally unsatisfactory (and, a hundred years later, engineers are still looking for a satisfactory way to get rid of sludge!). Wynberg took an option on a piece of State ground between Zeekoevlei and the sea for the purpose of a new disposal site and constructed a new works there. In due course this became the huge Cape Flats Treatment Works.

Stewart's commissions were not confined to the Cape Peninsula. Outside of Cape Town, he designed the Johannesburg Waterworks at Zuurbekom, and provided supply systems for a number of other towns including Bloemfontein, Oudtshoorn, Worcester, and Stellenbosch. In 1912 little Riversdale employed him to sort out problems with the supply scheme designed by his old boss John Gamble some forty years earlier. He designed a new weir on the Vet River, but had a set-to with the local Council, who wanted their local foreman to carry out the construction. Stewart considered him incompetent, held out for his own man, and got his way.

In 1914 he was employed to design a water scheme for Beira.

The amalgamated Cape Town Municipality appointed the extremely capable David Lloyd-Davies to head up its engineering department. He had to give his immediate attention to sorting out the by now desperately urgent water shortage, and after considering various options decided in favour of the Steenbras scheme. Stewart, W.A. Tait and Lloyd-Davies formed the Board of Engineers responsible for the design of the dam and delivery pipeline, and we can assume that most of the creative work was in Stewart's hands.

Stewart's services were much more than mere dam design, and involved hydraulics and hydrology, as well as a decent grasp of finance and economics. And, if we are to judge from his report to Wynberg on the proposed sewerage scheme, his written documents were models of their kind.

1932, on the 50th anniversary of his arrival in South Africa, the leading local engineers presented him with an illuminated address to mark the occasion, and to express their admiration for the achievements of "the doyen of the profession in South Africa". The signatories are a galaxy of the leading practitioners of the times and include Kanthack, George Stewart, Alfred Snape, and a young Ninham Shand, who was just starting out as a consultant. A further unusual honour came Stewart's way in 1936 when the President of the Institution of Civil Engineers in London wrote to him to express the appreciation of the membership for his long and distinguished connection with the body. He had in fact, while still a student, been awarded the Miller Prize for a paper entitled "The Prevention of Waste in Water", and later served as the Southern African representative on the ICE Council for two terms. He had become an Associate Member of the Institution in 1883, and a member, at a relatively young age, in 1893.

Stewart served as the second president of the Cape Society of Engineers (now SAICE) at the height of his professional powers in 1904. He was also elected as a Fellow of the Geological Society and served a term as the President of the Royal Society in South Africa.

He died at his home in Kenilworth in October 1942.

Tony Murray is a retired civil engineer who has developed an interest in local engineering history. He spent most of his career with the Divisional Council of the Cape and its successors, and ended in charge of the Engineering Department of the Cape Metropolitan Council. He has written extensively on various aspects of his profession, and became the first chairman of the History and Heritage Panel of the South African Institution of Civil Engineering. Among other achievements he was responsible for persuading the American Society of Civil Engineers to award International Engineering Heritage Landmark status to the Woodhead dam on Table Mountain and the Lighthouse at Cape Agulhas. After serving for 10 years on SAICE Executive Board, in 2010 he received the rare honour of being made an Honorary Fellow of the Institution. Tony has written manuals, prepared lectures and developed extensive PowerPoint presentations on ways in which the relationship between municipal councillors and engineers can be more effective, and he has presented the course around the country. He has been a popular lecturer at UCT Summer School and has presented five series of talks about engineers and their achievements. He was President of the Owl Club in 2011. His book "Ninham Shand – the Man, the Practice", the story of the well-known consulting engineer and the company he founded, was published in 2010. In 2015 “Megastructures and Masterminds”, stories of some South African civil engineers and their achievements was written for the general public and appeared on the shelves of good bookstores. “Past Masters” a collection of his articles about 19th century South African Engineers is also available from the SAICE Bookshop.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.