Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

South Africa was one of the last bastions for steam locomotives and they attracted many tourists from across the globe to travel on our trains or watch them go by, camera at the ready. Steam engines have an enduring appeal to railway enthusiasts (buffs & gricers will also do) as they seem to live and breathe just like a wild animal. In fact it was seriously considered to make a “Reserve” for steam engines along the Garden Route, in the province of the Western Cape, centred on the city of George, where a Steam Museum resides. Alas Mother Nature intervened, when a land slip, after torrential rain between the 1st & 3rd August 2006 (300mm), closed indefinitely the 42 mile (67km) long branch line from George to Knysna, on which the steam hauled “Outeniqua Choo Tjoe” ran. The branch was the showpiece for the Transnet Heritage Foundation and it was run on similar lines to a “Preservation Line” in the UK and it was often referred to as “the world in one branch line”. Its closure was a great set back, let us hope that one day it will re-open again.

Outeniqua Choo Tjoe crossing the Kaaiman’s River bridge (Peter Ball)

The reason for the longevity of the steam engine in South Africa is due to politics and economics. South Africa was blessed with a treasure trove of natural resources, but the one that mattered most it did not have, Oil (the “Achilles heel"). Apartheid (since 1948) had brought forth condemnation from the rest of the world, which prompted external boycotts, embargos and sanctions, which were applied increasingly to try and change the status quo and bring about a peaceful transition to create a just multi-racial society, which thankfully happened in 1994. Of all the external pressures applied to the Nationalist government the most effective and damaging was the Oil embargo, as it proved to be the one that they could not easily counter.

When the Union of South Africa was formed on May 31, 1910 the preceding colonial railways were amalgamated to become the South African Railways (SAR), however the merger of the constituents; namely the Cape Government, Railways, the Natal Government Railways and the Central South African Railways, would not happen “over night” and it would take until 1916 for full unification. The SAR would go forward under the able administration of its General Manager, William Hoy (ex CGR). In 1916 Steam power was still the dominant force in railway operations around the world and it had no immediate rival, but as early as 1912 Hoy, who was a forward thinker, was aware of the long term possibilities of electric traction, however it would take him another 10 years before he could put his ideas into practice. He was also a keen supporter of the internal combustion engine and advised that instead of the added expense of taking branch lines further into the country districts, there should be instead provision made for rail heads to be served by lorries and buses that could fan out to the surrounding “dorps” (small towns).

Sir William Hoy

There is a tendency to think that steam power should have been made redundant as quickly as possible, as was the case in Britain, when within the space of 10 years (1958 to 1968) all the steam locomotives were sent to the scrapheap to be replaced by (“dodgey”) diesels at great expense to the tax payer. However SAR took a longer term view and it was always the case that electric traction was to be the future no matter how long it took to provide the necessary infrastructure. Both the steam engine and the electric loco are powered by coal, the difference between the two being that the former has its own power plant (firebox & boiler for steam raising), whereas the latter received its electric power from a coal fired thermal power station, through the National Grid. As South Africa had coal aplenty (and thus was self-sufficient) it was the logical choice to use coal as a fuel, both for economic and strategic reasons, as the alternative to oil (the supply of which could be cut off).

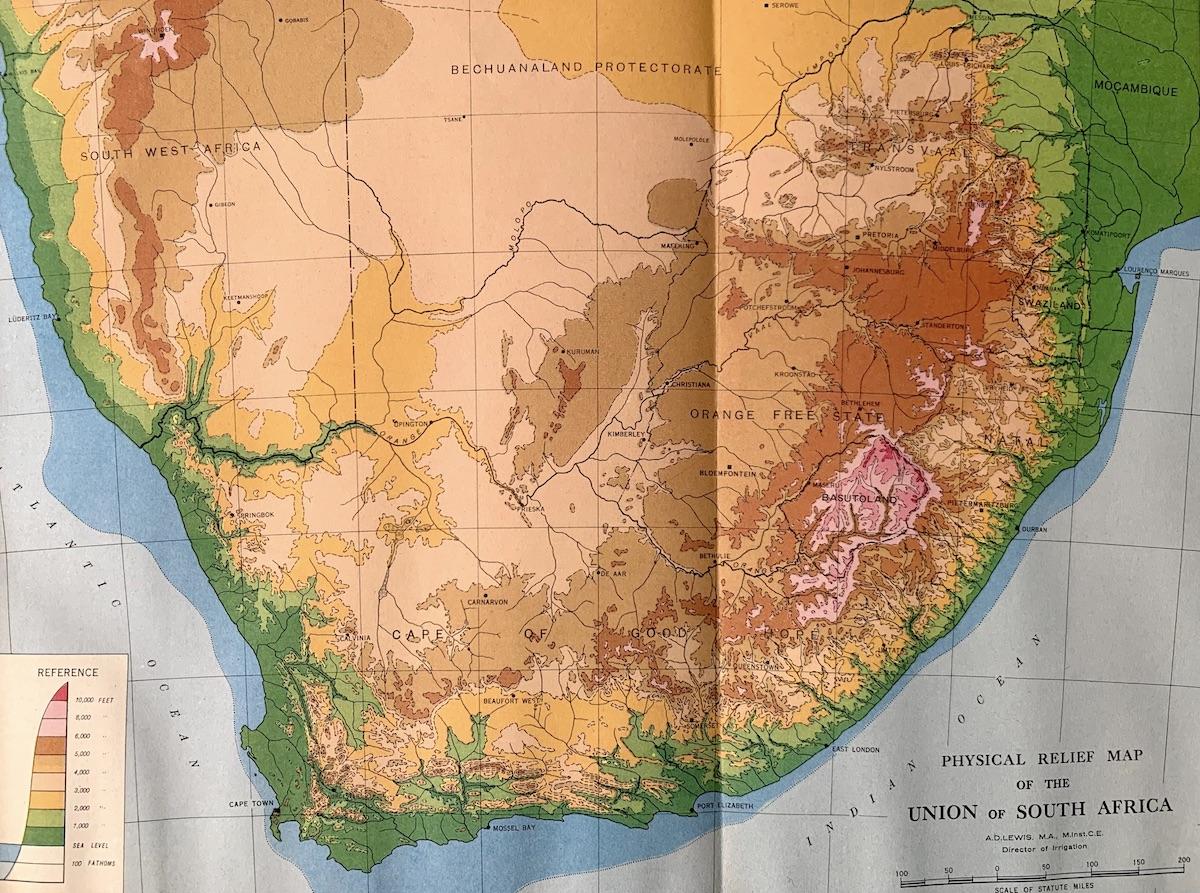

Going back in time to the last quarter of the 19th century, little interest was shown for extending the existing railways of Cape Town & Durban into the interior as there was no economic reason to do so. The discovery of diamonds (1867) and gold (1886) changed everything and would be the impetus needed to build railway lines first to Kimberley (reached in 1885) and then to Johannesburg (reached in 1892). Interestingly Johannesburg was not reached by an extension from Kimberley, but instead via Bloemfontein and it would not be until 1906 that the direct line joining the two mining towns would be opened (see “Race to the Rand”). The topography of South Africa was another deterrent to the building of railways into the interior as the escarpment had to be surmounted to reach the “Highveld”. It was especially so from the port of Durban, which made the Natal Main Line the hardest to build and operate with gradients as steep as 1 in 30 in places and the curves as sharp at 4½ chains or 297 feet radius (90.5m).

Physical Relief map of SA (The SA Railways - History-Scope-Organisation)

The Natal Government Railways would build the Natal Main Line from Durban to Charlestown (on the Transvaal border, close to the town of Volksrust) and it would open in stages: Durban to Pietermaritzburg (1876 to 1880), Pietermaritzburg to Ladysmith (1880 to 1886), Ladysmith to Charlestown (1887 to 1891) with every intention to push on towards Johannesburg with the co-operation of the NZASM – the railway system of the Transvaal (duly done, 1894 to 1896). The line proved to be difficult to operate with steam engines notwithstanding the many upgrades and re-alignments of the permanent way between 1891 and 1921. William Hoy realised that this line was ripe for electrification and enlisted the expertise of the Newcastle-on-Tyne consultants, Merz & McLellan, the then leaders in the field of railway electrification. They in turn submitted a report in June 1919, followed up by a visit by their senior partner, Charles Merz in August of that year. The Report recommended commencing the electrification (at 3000 V dc) from the Durban end and then progressing inland, however the shortage of finances at the time meant that the electrification could only be made in stages and thus priority was given to the Pietermaritzburg to Glencoe section, as it was then only a single track and it was reaching its full capacity under steam power.

This first stage would fully open on April 14, 1926, although the short section between Diamana and Chieveley had been energised on October 1, 1924 for testing purposes. Durban would have to wait for another 10 years, until December 1, 1936 for electrification to arrive, when the electric service was officially opened by the Minister of Railways and Harbours, Oswald Pirow. The northern end of the Natal main line, between Glencoe and Volksrust would have to wait a little longer and would be electrified in conjunction with track re-alignment works, under the “Ten million pound scheme”, which provided work for the unemployed during “The Great Depression”. A restricted electric service was first brought into operation on October 3, 1937, thereby extending electric traction the entire length of the Natal main line – Durban to Volksrust.

First electric locomotive Class 1E (Railways October 1979)

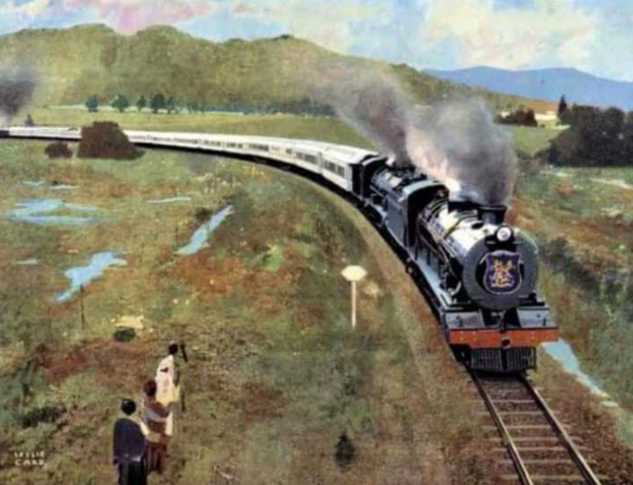

The Second World War (1939-1945) would intervene and delay further plans for main line electrification and at war’s end the SAR would still be predominately reliant on steam motive power bar the Natal Main Line and the suburban services of Cape Town (at 1500 volts dc) and Johannesburg (3000 volts dc) completed pre-war. Steam still had a future and new classes of steam engines were on the drawing board for main line and branch line work namely Class 24 (2-8-4), Class 25 & 25NC(4-8-4), and the GMA/M (4-8-2 + 2-8-4 Beyer-Garratts). Peacetime brought back normality and in 1946 the Blue Train was re-introduced and in 1947 the White Train took King George VI and Queen Elizabeth and the Princesses on the Royal Tour of the Union.

Painting of the White Train on the section between Cathcart and Queenstown

1948 was election year and the shock defeat of Jan Smuts’ United party at the polls, ushered in the Apartheid Era. The 1950s & 60s saw incremental increases in the installation of overhead wires to the main lines out of Pretoria, Johannesburg (Jhb) and Cape Town such that by 1963, Pretoria-Komatipoort, Jhb-Kimberley, Jhb-Volksrust and Cape Town-Beaufort West were all electrified to 3kV dc.

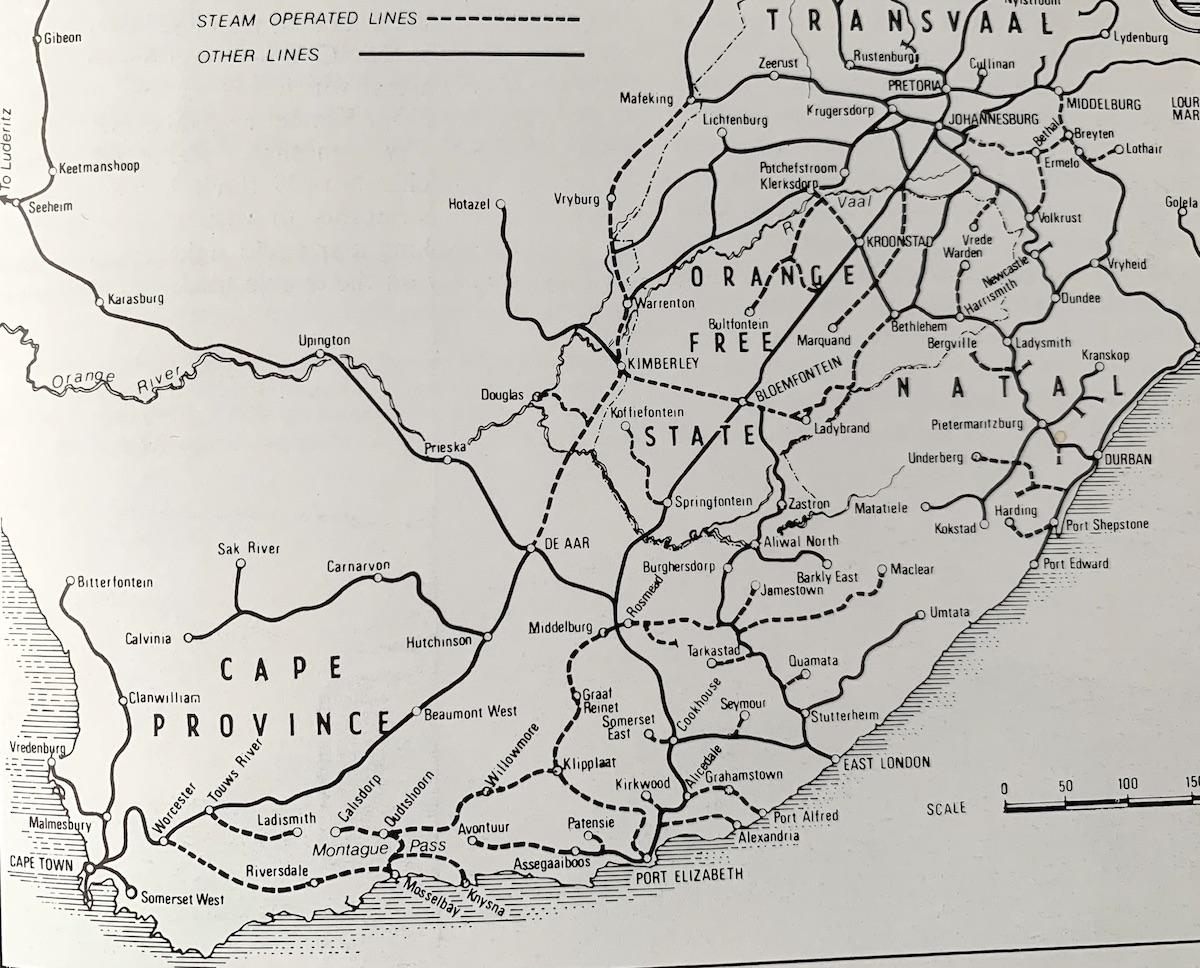

The first diesel-electric locomotives were introduced in 1958 and ran initially on the main line between Johannesburg and Volksrust before electrification; they were of American design and were manufactured by General Electric (GE) and designated by them as U12B. SAR designated them as DE1, but later were to re-classify them as Class 31. A year later a bigger and more powerful version - the U18C1 from GE came into service to become SAR Class 32 and these would take over all services to and from and within South West Africa (now Namibia). This action would pension off the venerable ex CGR Class 7’s (4-8-0) and re-allocate the 10 year old Class 24 back to South Africa for branch line work. The reason for the dieselisation of all services north west of De Aar Junction (i.e. towards SWA) was based not only on the expense of railing coal supplies from Witbank to the “Fifth Province”, but also because of the perennial water supply shortages experienced in replenishing the steam engines’ boilers. Dieselisation was then deemed an economic solution as the Arab Oil embargo was yet to bight.

Railway map of SA circa 1979 (Railway World Annual 1981)

By the 1970s the writing was on the wall for steam and the official policy was to phase it out by the early 1990s, thus there was an “Indian Summer” (final flourish) period, in the 1970s & 80s, whereby rail tours were organised for overseas tourists to be of course hauled by shiny black steam locomotives. One such rail tour is worthy of mention as it covered 2000 miles (3218km) of continuous steam haulage behind thirteen different types of steam engine, over a period of ten days, in April 1979. The rail tour was called “The Sunset Limited” and was organised by the Railway Society of Southern Africa and it journeyed from Johannesburg to Mossel Bay and return, mainly travelling by day. Tickets were sold out way in advance and many of its 170 passengers had come from overseas. I was very lucky to be invited to a talk (some years ago now) on this very rail tour by someone who was on board, Mr. Graham Du Plessis, a railway modeller and an Oracle on all things SAR and his recollections made one envious.

The Sunset Ltd (Railways August 1979)

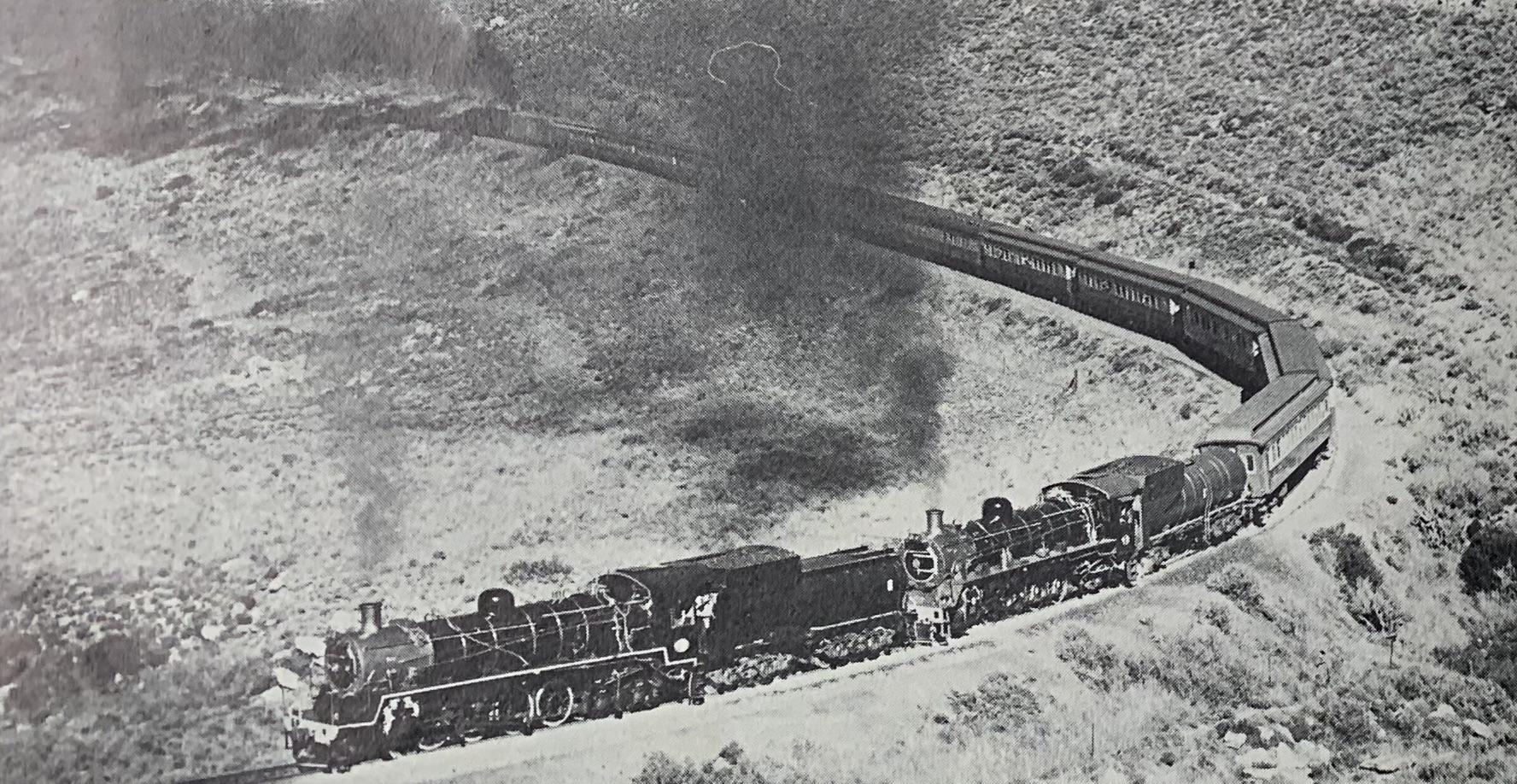

Later that same year (1979) another rail trip was documented in an episode of the BBC TV series “Great Railway Journeys of the World”; the episode was entitled “The Zambezi Express” and it was a once off trip taken by the historian and broadcaster, Michael Wood, from Cape Town to the Victoria Falls just prior to the cease fire in the Rhodesian Bush War. Even now, 42 years on the documentary still has a special appeal to it and is worth watching. The scene where two giant Class 25NC steam engines named Maria and Jennifer are double-heading a northbound freight at speed is amazing, especially as Michael Wood is standing on the foot plate of the second engine holding on tightly to the pole between cab and tender.

Double headed Class 25NC (Twilight of SA Steam)

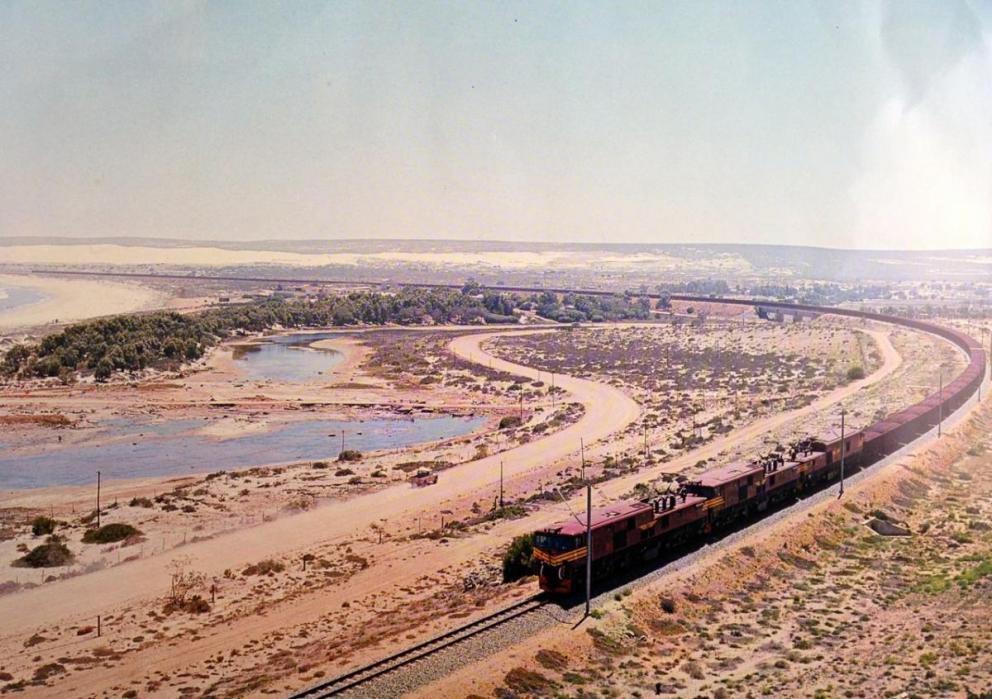

South African Railways would change its name (and image) in 1981 to the South African Transport Services (SATS) and then again to Transnet in 1990, when the railways became a limited liability company – Transnet SOC Ltd. Transnet Freight Rail would be its largest subsidiary and was the inheritor of the heavy haul lines, purpose built during the 1970’s, for the export of minerals. The lines in question are: the Coal Line from Ermelo to Richards Bay and the Orex Line from Sishen to Saldanha Bay. They are not really part of story of the “transition from steam” suffice to say that these two dedicated lines, running from Pit to Port, can work heavily laden trains, 2.5km and 4km long respectively. Electric traction was chosen as the best motive power option over diesel power, steam was not even considered as it had had its day.

Long train on the Orex line (SAR 1979)

References and further reading:

- “The Outeniqua Choo Tjoe, something to chew on” by Peter Ball, Heritage Portal.

- “Race to the Rand” by Peter Ball, Heritage Portal

- “HOY, the man who laid the foundation of SAR”, a profile in the “RAILWAYS” magazine, October 1979.

- “The South African Railways – History, Scope and Organisation”, published by the SAR, 1947.

- “The Natal Main Line Story” by Heinie Heydenrych & Bruno Martin, published by HSRC Publishers, 1992.

- “Railways of Southern Africa” by O.S. Nock, published by Adam & Charles Black, 1971.

- “This is South African Railways, 1977/78”, Editor: Justin Haler, published by Thomson, 1978.

- “Twilight of South African Steam”, by Dusty Durrant, published by David & Charles, 1989.

- “Tracks Across the Veld” by Boon Boonzaaier, published by JNC Boonzaaier, 2008.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.