Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

Now I have to say from the very outset that I am “old school” and therefore know relatively little of the workings of Building Information Modelling (BIM), but being a keen observer of the built environment I am aware of the benefits that its methodology can bring to a building project with the aid of sophisticated computer software, which is now at the fingertips of the Architect, Engineer and Contractor, whether the project be “Greenfield” (new) or “Brownfield” (existing).

Now what is BIM? As defined by The Institute of Structural Engineers, London “It is an approach centred on using digital tools to efficiently produce information to allow assets to be built, operated and maintained. It relies on all those involved in the project fully populating a central data base” (i.e. a three dimensional computer model). This brief definition does not fully convey the power of BIM and so in order to give more weight to the topic I refer the reader to the web site of the “BIM Institute” (www.biminstute.org.za), where he/she can be the judge of the usefulness of BIM in their own field.

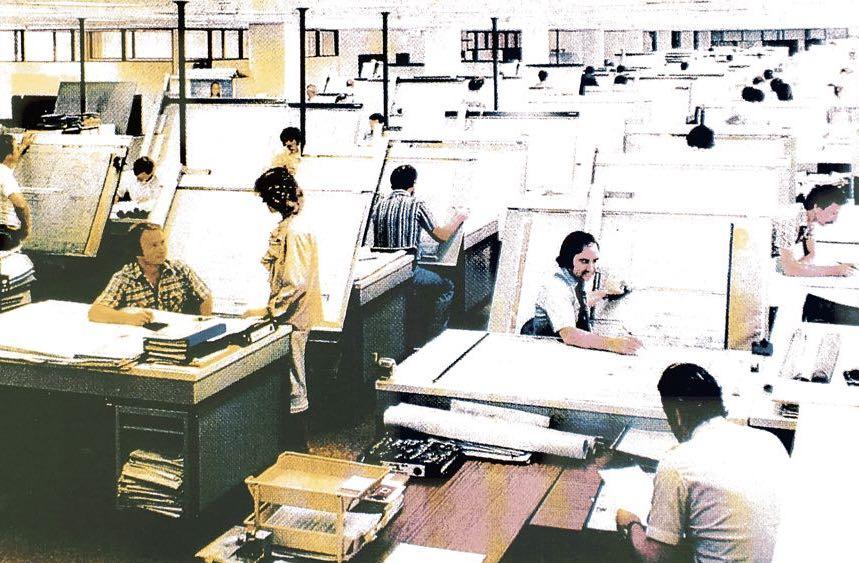

The saying goes that “the only constant is change” and that is certainly true with regard to the building industry, where the competitive edge is of great importance in winning contracts. In the last 50 years there have been great strides made in the way a building project is brought to completion and in my own experience I could never have anticipated the developments that have occurred since I first joined a consulting engineer’s drawing office in the mid 1960's. Whenever I smell ammonia it takes me back to those days of ammonia printers when making prints of “double elephant” imperial size (26in x 40in) drawings. Back then drawings were drawn by hand by trained draughtsman from sketches and calculations done by qualified designers; prints of those drawings (2D) would be delivered to the building site and in due course a new building would arise on the skyline. Note that General Arrangements were drawn to a scale of ¼ inch to the foot (approx. 1:50) and detail drawings to ½ inch to the foot (approx. 1:25).

As the world (& my career) progressed, working in a drawing office was made a little easier when the slide rule gave way to the electronic calculator during the 1970’s and structural analysis, previously done by hand methods, was increasingly being carried out by computer programmes using a mainframe computer, albeit at a high cost. It was not until the 1980’s, when the IBM PC revolutionised electronic computing that electronic design and draughting became affordable and widely available.

With all this new technology coming on stream, a paradigm shift occurred and the days of the old drawing office were numbered and the rows of AO size drawing boards were to be a thing of the past (by the mid 1990’s) and Computer Aided Design & Drawing (CADD) would become the norm. Note that a paradigm is a pattern or model and a paradigm shift occurs when people change from an established mode to an updated one; furthermore the shift is never immediate and rarely is it smooth.

The “Baby Boomer” generation of draughtsmen, designers, engineers and architects who started work in the pre-computer age, during the 1960’s, and filled those drawing offices of yore, have with the odd exception, all retired and have passed the mantle of planning designing and delivering construction projects onto the next generation now midway through their careers (who were brought up more “tech savvy”) and are now working with the new paradigm of using the computer for architectural conceptualisation, structural analysis and design and the production of drawings for construction as well as the functions of planning, management and quantity surveying.

The acronym, BIM has become the buzzword for efficient project delivery and BIM’s merits have been taken seriously in the United Kingdom, where its Government has mandated its use since 2016 on all public works, so as to achieve cost savings, and improved value and carbon footprint performance through the use of shareable information.

The ideas behind BIM have been around for sometime (at least since the mid 1980’s) and there is now a recently issued international standard – ISO 19650 (an update of British Standard, PAS 1192) to take BIM into the future, but what of the past.

Let us take as an example one of the most iconic buildings of the twentieth century – the Empire State Building (ESB), 350, 5th Avenue, Manhattan, New York City, which opened its doors on the 1st May 1931. The Art Deco skyscraper was at the time the tallest building in the world at 102 floors (1 250 feet to the roof), surpassing the Chrysler Building (refer to www.esbnyc.com for more information).

The high degree of co-ordination achieved by the ESB project team has rarely been bettered and their efforts could well be considered as the genesis of the BIM process, albeit without the aid of a computer model. Over a 90 year life span the ESB has had three phases as follows:

Phase 1: Design and Planning (1929).

Phase 2: Construction (Oct. 1929-April 1931)

Phase 3: Occupation, Maintenance and Upgrades (May 1931 to date)

The above highlights the fact that Phase 3 has had the longest duration and is subject to the building being kept in good order with a maintenance plan being in place.

A Phase 4 could be added which would be its demolition and disposal, something that was not considered in the planning. It just so happens that a book has been written by David Macaulay on how to dismantle the ESB, entitled “Unbuilding”, which is a fictional account, for young readers, of an Arab prince from an oil rich state who has bought the ESB and wishes to re-erect it in the Arabian desert. Macaulay, an accomplished illustrator, produces a fine set of drawings in perspective to explain the technicalities of dismantling the steel framed building.

What if the Empire State Building was being built today, could BIM improve on the performance of the original project team? Well in my humble opinion it would be a difficult feat as the ESB went up in record time, managing 4½ storeys a week! It could well be argued that the reason for the ESB being completed ahead of schedule and within budget was because the construction phase was at the beginning of the Great Depression (which lasted from 1929 to 1939) and all parties were under great pressure to deliver and keep productivity up and costs down.

BIM (forget Bam & Boom) is the future for the construction industry and its methodology will increasingly be honed by experience in its use for buildings, bridges and infrastructure projects across the globe.

References and further reading:

- “BIM and Structural Engineering – the industry now and in the future” by Desiree P. Mackey, STRUCTURE magazine, January 2017. P46-49 incl.

- “The Empire State Building Book” by Jonathan Goldman, published by St. Martin’s Press N.Y. 1980.

- “Unbuilding” by David Macaulay, published by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 1980.

- “Autodesk Revit Architecture Essentials Level 1”, Student Guide, 2014.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.