Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

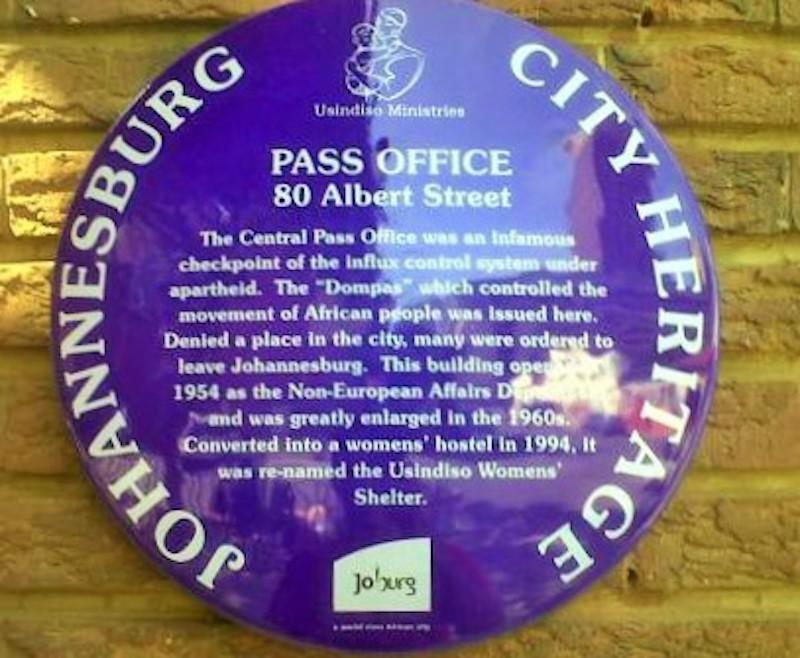

In June 1954, a new building was completed at 80 Albert Street to the east of the Johannesburg CBD (just south of the Barclays / ABSA precinct today). It was designed as the head office of Johannesburg’s Non-European Affairs Department (JNEAD) and became the nerve centre for controlling the lives of black people in Johannesburg for over three decades. Despite having great cultural significance, the building’s controversial and complex history remains relatively unknown outside heritage circles.

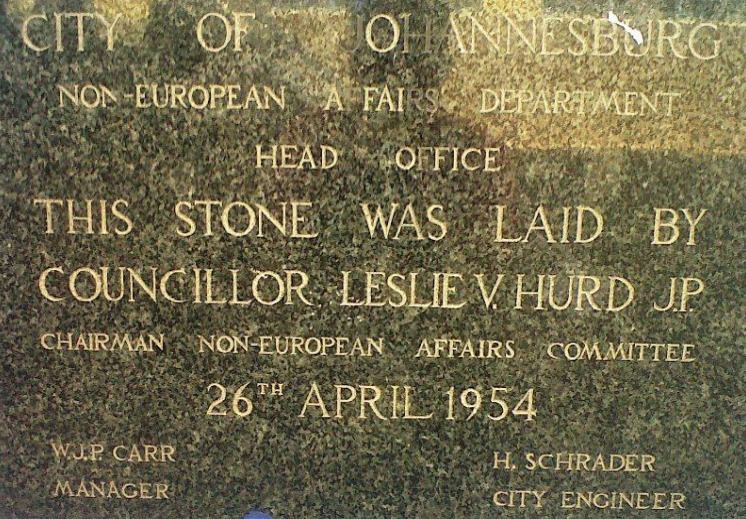

The Foundation Stone (The Heritage Portal)

At its inception in 1927, the JNEAD consisted of a Manager, four clerks and a typist as well as a handful of superintendents in the field. By the early 1970s, shortly before the West Rand Administration Board (WRAB) took over ‘Urban African Administration’ from the Johannesburg City Council, the JNEAD was an enormous organisation employing approximately three and half thousand people and overseeing almost every aspect of 'urban African life'. The growth of the Department was a response to one of the most complex situations confronting any local authority in the world. The huge industrial growth of Johannesburg had led to an exponential increase in the size of the black population and the Department’s response was a rapid expansion to exert greater control.

The paragraphs below unpack the various functions of the Johannesburg Non-European Affairs Department and reveal a different era in our city’s history that many may find difficult to believe today.

80 Albert Street from above (The Heritage Portal)

The Registration Branch

One of the most notorious functions carried out by the Department was its responsibility for influx control and employment. Apartheid legislation provided the framework for tight control over the movement of black people in urban areas. The law required all work seekers and employers to refer their requirements to the local labour bureau. If there was a shortage of labour in any area, permission could be granted by the government for ‘outsiders’ to enter under a permit system. Officials within the department had great power to determine the fate of individuals. WJP Carr, the long-serving manager of the JNEAD, urged officials to act as humanely as possibly under difficult circumstances. Many did not.

The Registration Branch was inaugurated on 1 July 1953 when the Council took over control of the registration of service contracts and the operation of a male labour bureau from the Central Government. Over 280 000 reference books were issued between August and December 1953, a huge task which led to the City Council approving extensions to 80 Albert Street while it was still under construction.

Another function of the Branch (conducted at 80 Albert Street) was the invasive medical examination. No black person could be certified for work unless declared medically fit. The examination (with little privacy) involved a general physical inspection, a chest X-ray to test for tuberculosis, vaccinations against smallpox and in some case blood tests for typhoid and venereal disease. In 1960 almost one hundred thousand examinations were carried out.

On 9 January 1959 labour regulations were made applicable to women. The legislation had been in place since 1952 but had not been enforced for political and administrative reasons. Temporary arrangements were made for operations to be carried out at 80 Albert Street while facilities at 1 Polly Street around the corner were prepared. The female labour bureau was officially opened on 1 March 1959 and a medical examination and X-ray unit came into operation in 1961.

80 Albert Street was also known as the Pass Office. The work of the Registration Branch gave it this name.

The Information Section

The main aim of the Information Section was to communicate the various operational aspects of the JNEAD to the people of Johannesburg (black and white). There was an element of propaganda in this task as officials attempted to reduce what they saw as ‘ill-informed criticism’ of the Department.

The information officer disseminated regular updates to a spectrum of newspapers and radio stations and produced brochures dealing with subjects ranging from housing and welfare to employer-employee relations. The brochure ‘Thousands for Houses’ which documented the positive aspects of the City Council’s massive housing programme in the 1950s required several print runs to keep up with demand from Central Government. It appears as if it was used to influence international opinion with the Department of Information ordering a thousand copies for its offices in the United States and another thousand for its offices around the world. Another widely distributed publication was the advice booklet ‘Your Bantu Servant and You’ which was handed out to employers at the European counter of the Registration Branch at 80 Albert Street. It contained recommendations on how to treat employees 'compassionately and sensitively' to improve race relations.

The Research Section

This section was closely integrated into the Head Office administration and conducted a wide range of surveys and investigations into the lives of black people in the city and trends in ‘Urban African Administration’. At various times this section provided detailed information on family size, occupations, wages, social conditions etc. It also attempted to forecast population growth patterns and housing requirements. This information was invaluable to the Manager of the JNEAD as well as other council departments for planning and policy purposes.

Township Superintendents

Administration on the ground was the responsibility of township superintendents. They had jurisdiction over an area of approximately two to three thousand households and, as with all JNEAD officials, were expected to implement government policy and regulations. Superintendents were responsible for maintaining law and order, collecting rents, allocating welfare services, providing information and advice, and settling disputes within the community. They also had the power to allocate trading sites and demolish illegal structures. The township superintendent was the chairman of the local Advisory Board and was required to keep ‘Head Office’ informed of progress regarding service delivery as well as any significant issues that could affect the stability of the community. As the JNEAD expanded rapidly in the 1950s and 1960s so did the superintendent’s staff of black clerks. These clerks acted as the eyes and ears of the Department and played a key role in ensuring that the local office ran smoothly. Superintendents were often placed in difficult positions when having to communicate government policy to communities on the ground.

The Inspectorate Division

The administration and legislation affecting the presence of black people in Johannesburg was controversial, complex and seldom understood by employers and employees. Reference books were often deliberately lost or damaged by employees while employers regularly disregarded what they perceived as an irritating bureaucracy. One of the strategies to improve compliance was the establishment of the Inspectorate Division. Inspectors were sent to flat premises to scrutinise servants’ living quarters to prevent overcrowding and checked on employers who had defaulted on their services levy or services contract payments. The general practice, however was to warn and assist employers rather than issue summonses. At the height of its activities the Branch conducted over eight thousand routine inspections of employers’ premises per year.

Despite these efforts the Inspectorate was plagued by capacity issues and many transgressions were overlooked, ignored or missed altogether. The fraudulent alteration of registration documents became a major problem in the 1950s and 1960s. The use of official rubber stamps stolen from Albert Street resulted in thousands of men and women obtaining forged documents. Many enterprising individuals made a tidy profit from this activity. In order to combat the practice the South African Police strengthened a special unit based in Auckland Park and asked for experienced inspectors from the JNEAD to be made available.

Beer Brewing

In December 1937, the City Council decided to exercise its powers under the 1923 Native (Urban Areas) Act to brew and sell African beer. The JNEAD established a separate branch to control the entire enterprise from the construction and operation of breweries to the distribution and sale of product in specially designed beer halls and beer gardens around the city. From the late 1930s until the mid-1960s, the municipal monopoly on African beer generated profits of over eighteen million rand. Two thirds of the profits could be used to off-set losses from housing schemes while the remaining third could be spent on any service to improve the social or recreational amenities in an African area.

From a 2016 perspective it is hard to imagine such an extensive (and controversial) operation existing.

The Recreation and Community Services Branch

In 1938, with the profits from beer sales flowing into the Native Revenue Account, the JNEAD was able to establish a welfare section to assist families in need by providing food, clothing and in some cases cash grants. Over the decades the number and diversity of services provided to communities increased spectacularly driven by the council’s belief that without the social development of the community modern housing could deteriorate into slums. This required a simultaneous increase in the organisational capacity of the Recreation and Community Services Branch. By the mid 1960s this branch had over seven hundred employees and an annual budget in excess of a million rand.

The recreation sub-section of the Branch provided a wide range of sporting and entertainment facilities including football fields, tennis courts, swimming pools, golf courses, playgrounds and venues for film screenings and general entertainment. Department officials helped to organise school sporting leagues, adult football leagues and evening clubs for men to partake in boxing, weightlifting and bodybuilding. They even managed to arrange a few trips to the beach for small groups of children.

The JNEAD’s ability to maintain the quality and extent of these services was severely constrained during the 1960s as central government approval and loans were hard to come by.

The horticultural sub-section of the Branch aimed to beautify the townships by planting trees along the main streets. At the height of its activities over ten thousand trees were planted per year. Officials also encouraged residents to establish private gardens by running competitions and vegetable shows.

The Branch actively encouraged the pursuit of the arts. Music, dancing, ballet and painting were taught amongst others. The renowned artist Cecil Skotnes was in charge of the art centre located on Polly Street for many years.

A final community service worth mentioning was the operation of the Vocational Training Centre (VTC). It was registered with the Department of Education but managed by the Head Office Administration of the JNEAD. The Centre was one of the measures devised to combat juvenile delinquency during and after the Second World War and in its first year admitted forty students. By the mid-1960s over one hundred and eighty young men were enrolled and on average fifty-eight students qualified each year as artisans in terms of the Bantu Building Workers Act. The courses offered at the centre, at various times, included carpentry, plumbing, electrical wiring, motor mechanics and tailoring. After successfully completing a course many artisans were absorbed into various Council Departments including the Housing Division.

The Housing Division

Johannesburg experienced a severe housing crisis in the aftermath of the Second World War as local authorities, central government and employers attempted to avoid the financial burden of providing African housing. Losses borne by the Council and the Central Government reached nearly six hundred thousand rand a year by 1952 resulting in the Council’s building programme coming to a virtual standstill. As conditions within and surrounding Johannesburg deteriorated an urgent solution was needed. C.S. Goodman, Johannesburg’s Chief Housing Engineer in the late 1960s, identified three key breakthroughs that allowed the JCC to tackle the housing backlog. Firstly, the passing of the 1951 Native Building Workers Act which allowed the Council to train and employ African artisans lowering the cost of housing significantly. Secondly, the introduction of the Native Services Levy Act in 1952 which required all employers of African labour to pay a weekly sum for each employee they did not house. This money was placed in a fund earmarked for the provision of bulk services in the townships again reducing housing costs dramatically. The last breakthrough was the introduction of Site and Service schemes from 1953 which required municipalities to provide forty by seventy foot sites supplied with basic services on which African families could build temporary shelters. These shelters had to be built at the back of the site leaving the front available for the construction of a permanent home.

The measures allowed the JCC to create a formidable building machine that, at its height, completed over nine thousand houses in a year (1958-1959). From the early 1960s, however, activities in the Housing Division were curtailed due to limited government funding and the slow approval of housing schemes. This was in line with the Central Government’s push to reduce the urban black population to an absolute minimum. Instead of houses being built in Soweto the City Council was encouraged to finance houses in suitably placed homelands.

This ends our brief look at the functions of Johannesburg's Non European Affairs Department. For anyone looking for more in depth information and analysis click here.

Lucille Davie wrote a great piece in 2007 as well. Click here to read.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.