Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

The county of Cornwall, in England’s south west, is a well known holiday destination renowned for its scenic beauty and it comes as a surprise to many a visitor that the county has an industrial past. From the mid-18th century Cornwall was as industrialised as the Midlands and North of England and it was one of the most important metalliferous mining areas in the world. In fact the metal Tin had been exploited in Cornwall by the Romans in the 3rd & 4th centuries AD, after their previous source - the Spanish tin mines, were worked out. Tin was an important commodity in the ancient world as when alloyed with copper it produced bronze, which was superior to pure copper, because of its lower melting point, improved flow and increased hardness; items made from bronze were easier to fabricate and weapons and utensils were able to hold a sharp edge for longer.

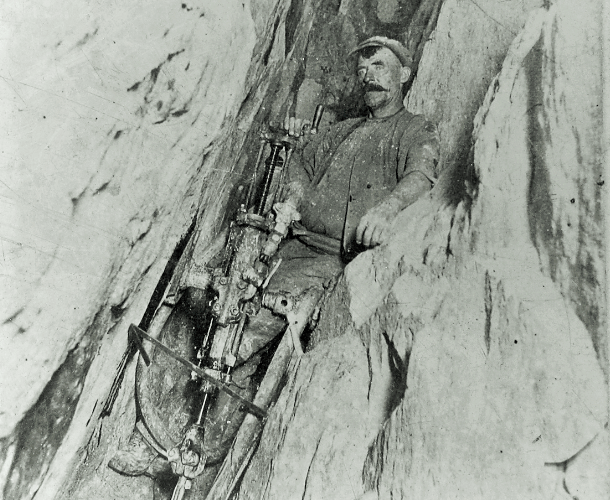

While Europe (as well as other parts of Britain) specialised in surface and underground coal mining i.e. soft-rock mining, the Cornish mining industry toiled to release metals embedded in hard rock, such as lead, copper, zinc, silver, nickel and tin and thus Cornishmen became world leaders in deep level hard rock mining, at least until the early 20th century.

It so happened that as the mines of Cornwall went into decline, circa 1865, major new ore bodies were being discovered across the globe. As the Cornish mines became spent (worked-out) and jobs were being lost there was a “Cornish Diaspora” to the far flung corners of the Earth. It has been estimated that 250 000 Cornish left their county in the period between 1870 and 1900 and they went as far afield as America, Canada, South America, Australia, New Zealand and not least South Africa.

Mining on the Rand

The Cornish first arrived in the Cape with the 1820 Settlers and more came in the 1850’s as the copper mines of Namaqualand (Springbok & O’Okiep) were being developed. By the 1870’s Cornishmen were finding there way to the diamond fields of Kimberley and were to later arrive in the Eastern Transvaal when gold was discovered in Barberton in 1884.

Surpassing all that went before was the discovery of gold on the Witwatersrand in 1886, which turned the bucolic and bankrupt South African Republic (a.k.a. Transvaal) from a backwater to the most bountiful country in all of Africa and Cornish miners were there from the outset of the gold rush.

Cornish Miners were there from the outset

As the gold mines along the Main Reef (from Springs to Krugersdorp) developed and began to go deeper more Cornishmen came over, starting their journey from West Cornwall by train in carriages with boards marked “Southampton”; the embarkation port for South Africa. In the ten years between 1890 and 1900 there was such an influx of Cornish miners that the mining camps resounded with their names – Tre, Pol & Pen (from the rhyming couplet “By Tre, Pol and Pen, shall ye know all Cornishmen”), Tre Pol & Pen are prefixes of Cornish surnames, e.g. Squire Trelawney, Captain Ross Poldark and Dolly Pentreath.

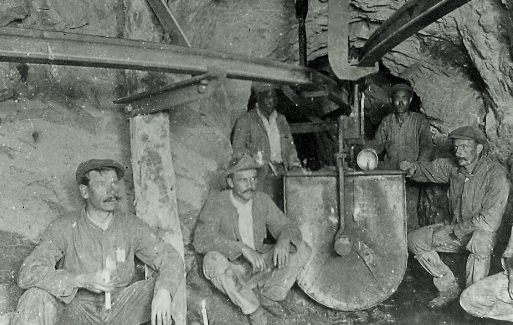

Wherever they went Cornishmen were known as “Cousin Jacks”, supposedly because if they could not do a job a cousin named Jack could; the Cornish were a close knit community and wherever possible looked after their own. Many came from the Camborne-Redruth area, where copper was mined and their mine occupations ranged from simply being a “miner” to being a drill sharp, a carpenter, a shaft timberman, a shift boss, a mine captain, right up to being the Mine Manager.

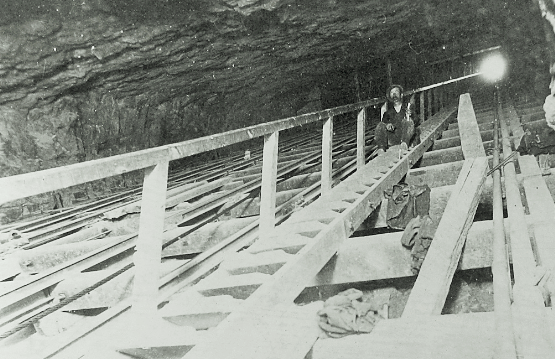

Old photo of a shaft on the Rand

It is said that the miners’ remittances (home pay) sent back to families in Cornwall was such a large amount of money leaving the country (£1 million per annum) that it forced President Paul Kruger to raise taxation on Uitlanders, thus exacerbating the situation between Burger and Brit, as the latter paid tax without representation in the Volksraad.

Being a hard rock miner was a tough way to earn a living and a miner’s life was often short, many dying in their early thirties, succumbing to the “ Miner’s complaint” – dust on the lungs which caused permanent harm and predisposed many to tuberculosis (TB).

The legacy of the Cornish Miners in South Africa is remembered in place names, such as Baragwanath in Soweto so named after John Albert Baragwanath who set up the Concordia Hotel, on the Kimberley road, as a stop over for the many prospectors entering the early diggings. Similarly the suburb of New Redruth, in Alberton, is named after Redruth, Cornwall and its streets are named after Cornish towns and villages.

Perhaps the biggest gift bestowed to South Africa by the Cornish was their love and preference for the oval ball over the round, as they are credited with introducing rugby football to this country, Amen.

References and Further Reading

- “South African Mining” by Anthony Hocking, Macdonald Heritage Library.

- “Digging Deep – A History of Mining in South Africa” by Jade Davenport.

- “The Discovery of Wealth” by Diko Van Zyl, Heritage Series: 19th century.

- “The Cornish Connection” by Janet Lee, in Mining Survey No. 2/4 1986.

- “Cornish Mining in South Africa” – Cornish Mining World Heritage.

- “Cornwall’s Industrial Past” by Russel Holt.

- “Mining in Cornwall – Camborne to Redruth” by L.J. Mullen.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.