Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

On Saturday 3rd August 2019 I delivered a talk to members of the Johannesburg Heritage Foundation entitled ‘Blue Plaques - Heritage History and Blue Lining our City.’ The Heritage Portal has had requests for at least some of the “take-aways” from this talk to help guide other South African heritage bodies. I will be delivering a talk on blue plaques in October at the HASA conference in Tulbagh. Meanwhile let’s skim over the subject of blue plaques and their possibilities. Click here to view South Africa's growing blue plaque database.

Northwards, Randlord Mansion, 21 Rockridge Road, Parktown (Kathy Munro)

When is heritage not heritage? When it is less than 20 years old? Or should that be 60 years or maybe venerably ancient at 100 years. In the United Kingdom the enduringly famous are only eligible for nomination for a blue plaque when he or she has departed this life 20 years ago. That was the dictum of English Heritage in London when they rejected the award of a blue plaque to extol the achievements of a footballer who is still playing. In Johannesburg we take a somewhat more relaxed view. We are a young city, only 133 years old and with heritage under threat the blue plaque is a powerful tool to recognize heritage survivals. The Johannesburg Heritage Foundation has a thriving and successful blue plaque programme and blue plaques are awarded for a range of notable achievements, remote and recent history, fine architecture etc. Blue plaques in our city have become a heritage meme to honour people, places and recall events.

During the past year Johannesburg Heritage installed over 20 blue plaques in the city. In the forthcoming year the organisation has plans to celebrate at least 21 places of history and heritage in the city with blue plaques.

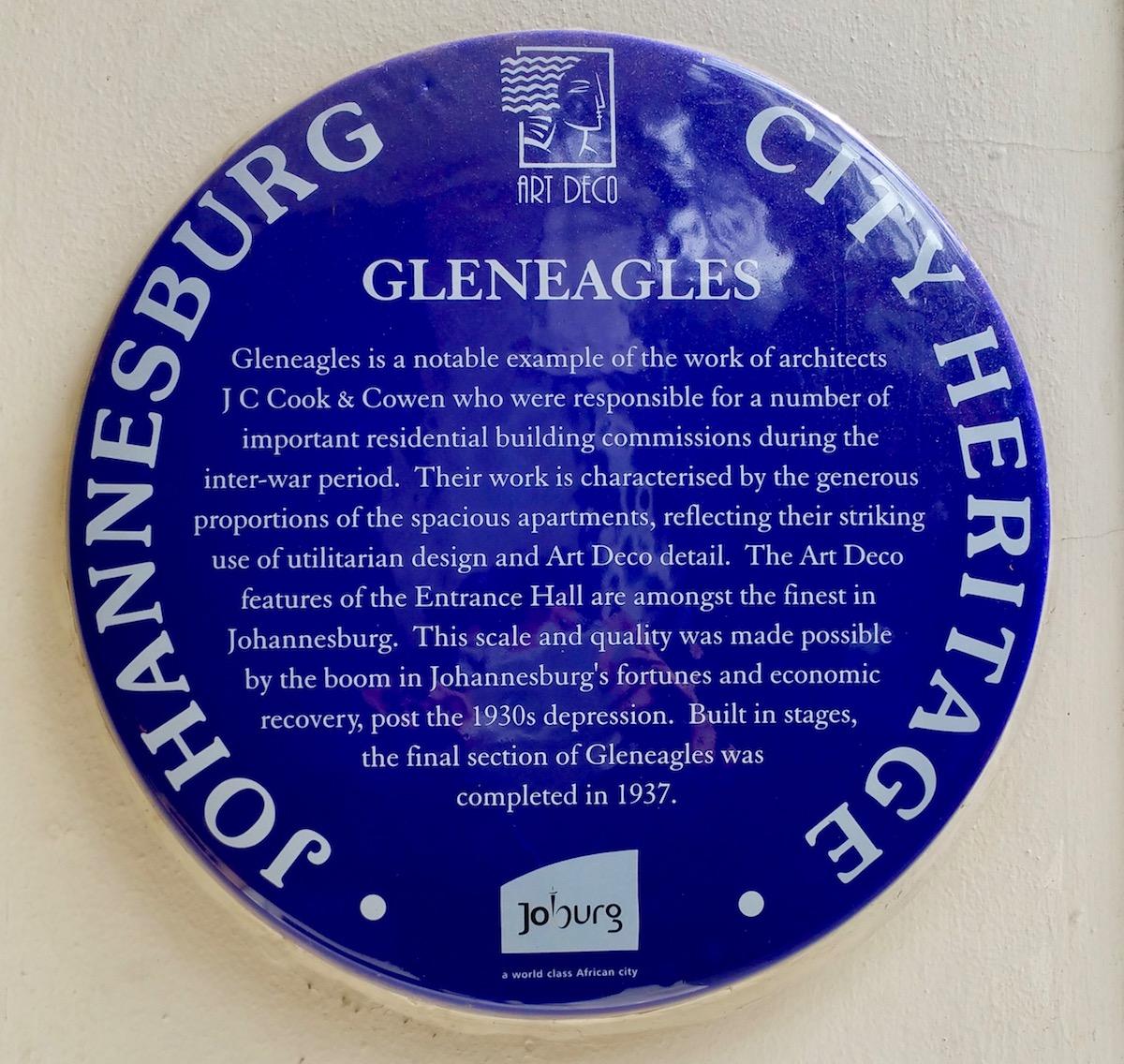

Johannesburg has embraced the idea of the blue plaque and its possibilities with pride and passion for over 30 years. It’s an idea that has wide appeal and the concept is easily grasped – a blue plaque means save this history. In Johannesburg there are several distinctive series of blue plaques such as Parktown Heritage, Johannesburg City Heritage, Art Deco, City Heritage, Architectural Legacy. Struggle Heroes and History, Alexandra Plaques and The Anglo-Boer War 1899-1902 centenary commemoration.

Gleneagles - part of the Art Deco series (The Heritage Portal)

The Parktown and Westcliff Heritage Trust was the predecessor of the Johannesburg Heritage Foundation and hence many of the pre 2013 blue plaques fell under their auspices and their original focus was to use the blue plaque as a means of drawing attention to the built heritage of Parktown that was being lost to motorways, offices, demolitions, change and development. A blue plaque will perhaps show a logo of the sponsoring organization or a logo indicating the theme and series.

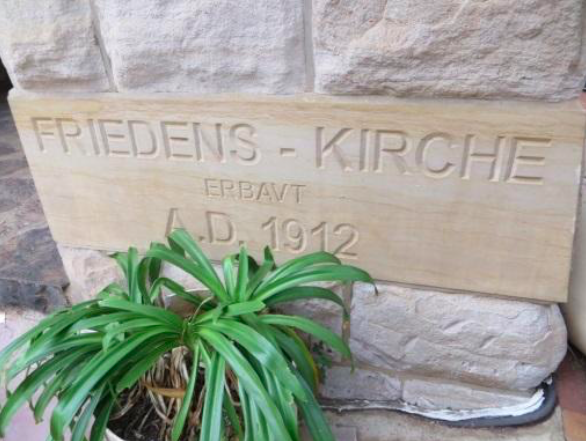

Stained Glass windows, blue plaque and foundation stone of the 1912 Lutheran Friedenskirche in Hillbrow (Brett McDougall)

A blue plaque plants the seed that perhaps a place is a spot to pause, reflect and take a second look. A blue plaque is a reminder that people who came before achieved something special. Blue plaques celebrate people, places, architecture and events. They are historical markers and spike curiosity. In less than 100 words the distinctive china blue, ceramic or fibre glass plaque gives a thumbnail explanation of the historical significance of a heritage worthy site. Some blue plaques have a QR code so that further information about a particular site can be sourced via the internet.

The blue plaque at Temple Israel, Reform Synagogue in Israel, 1936. Architects Kallenbach, Kennedy and Furner. (The Heritage Portal)

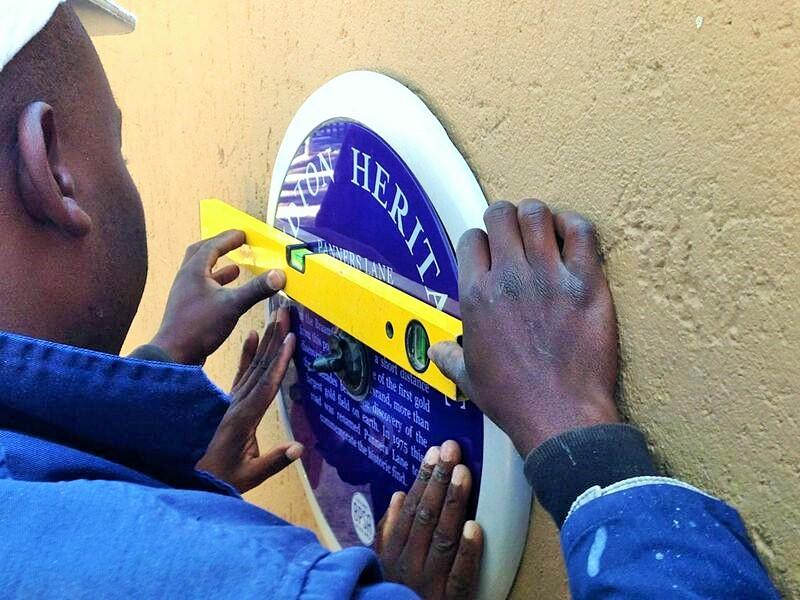

The plaque is circular in shape and measures 420 mm across; the material used was originally metal, later came a ceramic substrate and the latest is glass fibre. This is proving to be a durable option. The printing of the lettering is silkscreen with a UV varnish.

There are now several hundred blue plaques in Johannesburg but you will also find blue plaques in Pretoria, Cape Town and most recently the Magaliesberg.

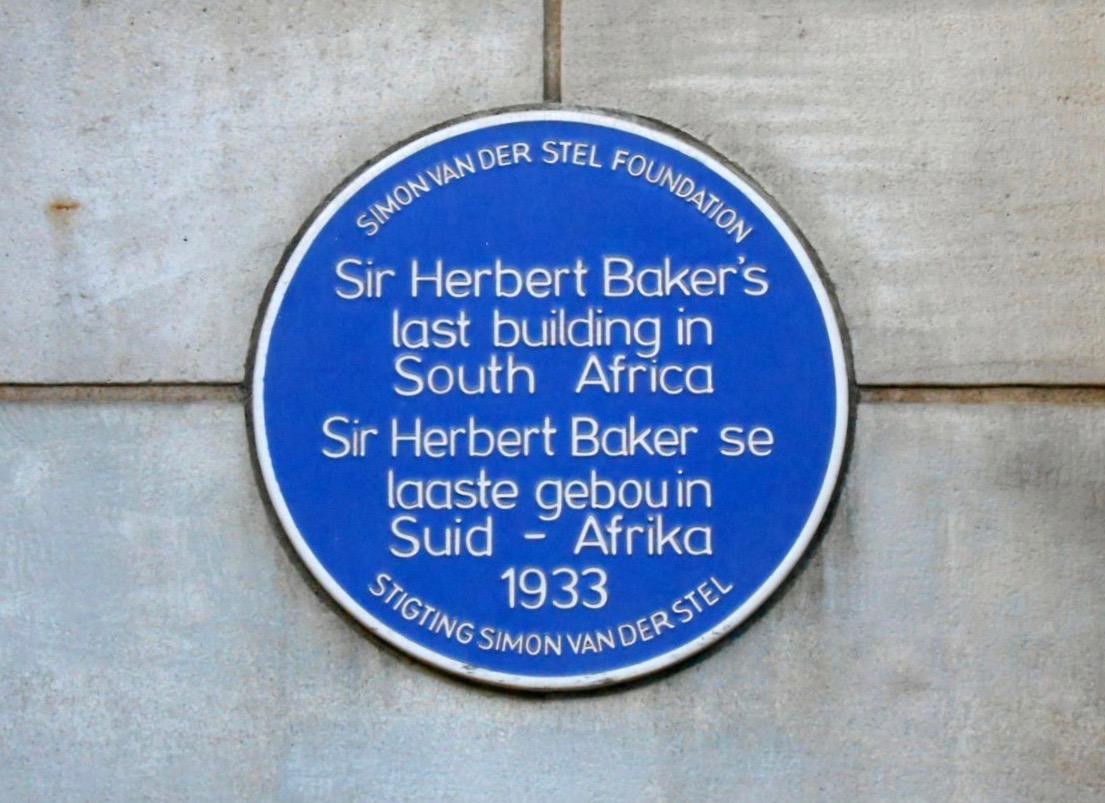

A blue plaque in Pretoria (The Heritage Portal)

In researching the origins of blue plaques in South Africa, I phoned Herbert Prins, the doyen of Heritage (and recently the recipient of a Gold Medal from Wits University). Herbert shared a little of the history the blue plaque and the role of the Simon van der Stel Foundation (this body is now the Heritage Association of South Africa and the Witwatersrand branch is Egoli Heritage). Herbert recalled that he was the person who brought the blue plaque idea to South Africa about 40 years ago, when he was the chair of the Witwatersrand branch of the Simon Van der Stel Foundation. The idea was drawn from London and English Heritage, but adapted and extended to meet a slightly different heritage context here.

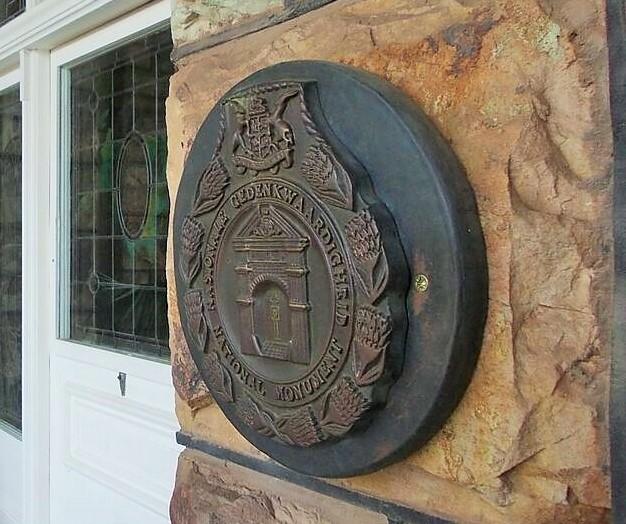

In the old days, the National Monuments Council was the State body responsible for electing and deciding upon national monuments in South Africa and a bronze logo with the Cape Town Castle embossed at the centre and the lettering of the National Monuments Council around the outer rim. North Lodge in Parktown, Northwards, Wits University’s Central Block and the Diaz Cross at Wits are all national monuments recognized with the now defunct logo. However, both North Lodge and Northwards also have later blue plaques.

Central Block at Wits (The Heritage Portal)

The old National Monuments Council plaque (The Heritage Portal)

The drawback of this insignia was that the same badge appeared on all declared national monuments but not all sites had an additional plaque providing details of the monument so the visitor was often none the wiser. Here was the opportunity to import and adapt the English approach to their heritage. The idea was to install the blue plaque on a building where it could be read with ease and so enhance the tourist’s experience.

Not all sites had inscriptions like this one at Boschendal (The Heritage Portal)

Further research is needed but it appears as though the first blue plaques were in Johannesburg. The Simon van der Stel Foundation had its headquarters in Cape Town and operated as a national body; thus in the early years the Witwatersrand chapter had to be franchised by the Simon Van Der Stel organization (strongly Cape based and operating within the prevailing dominant cultural white South African ethos) to be allowed to make blue plaques. This was a coup for Johannesburg as all blue plaques were supplied by the Witwatersrand Chapter. The South African blue plaque provided fuller information and was place specific; each plaque was unique to the heritage you were facing.

However, Herbert did not patent, copyright or brand the South African version of the blue plaque. Soon other bodies around the country embarked on their blue plaques adventure – first commissioning the Witwatersrand chapter to make plaques for them and then later doing their own thing. Herbert’s view was that a “a gentleman’s agreement” gave exclusivity to his initiative to be the manufacturer. As with all good ideas, the heritage lobby saw the blue plaque as a far more eye-catching, informative and appealing way to market heritage.

Cape Town also began to order and then make blue plaques for their history which was admittedly a few hundred years older than the gold mining roots of Johannesburg.

One of the Cape Town plaques (The Heritage Portal)

Move on to the eighties and the blue plaque idea really took off. The Star newspaper initiated the Johannesburg 100 committee in conjunction with the Johannesburg Historical Foundation led by Dr Oscar Norwich. 1986 was the centenary year. Heritage places, sites and buildings were nominated in the run up to 1986; each nomination led to a published photograph and joining a shortlist for consideration. Ultimately one hundred significant places were selected by the Jhb 100 Committee. Once the list had been finalised, the Simon Van der Stel Foundation was commissioned to make blue plaques which then appeared on each of the 100 sites with the City’s coat of arms appearing as the central logo.

A selection of the blue plaques of the Simon Van der Stel Foundation manufactured for the Johannesburg Centenary, 1986 – note the wording in English and Afrikaans and the Johannesburg 100 logo with the Coat of Arms of the city.

At the same time the Geological Society, in partnership with the S A Institute of Mining and Metallurgy (c 1986), installed a series of educational blue plaques; these plaques were strongly scientific, full of detail and diagrams. The plaques drew attention to the Witwatersrand and its unique geology and the discovery the gold bearing banket in reefs. We live on koppies, steep passes and cliffs; the geology is visible and yet Jozi people take it for granted. I recall one of these geological blue plaques on Jan Smuts on the cutting that reveals the mystery of the earth’s stratigraphy. Professor Mendelson of Wits was the driving force of that series. One of these blue plaques still survives on Kallenbach Drive. The Simon Van der Stel Foundation made the plaques.

The Geological Society Blue Plaque on Kallenbach Drive/Steepways Lane, Linksfield (Kathy Munro)

A book and fold out map appeared listing the geological sites of the Central Witwatersrand and the Jhb 100 heritage sites list was also included as an appendix. It was and still is a useful reference source and is now a collectors’ item.

Herbert Prins prides himself on his fatherly role in the evolution of the South African blue plaque movement; for many years he was consulted about the words on a plaque; were they accurate, were they fair, were they balanced did they tell the essential history? Quality control and expertise in historical and architectural research are essentials in preparing a blue plaque.

Then circa mid 1980s (Flo Bird says “about 30 years ago”) the Parktown and Westcliff Heritage Trust also discovered and began to install their own blue plaques. The blue plaque took on a new role - it became a weapon in the fight to save Parktown and their heritage homes - Northwards, the View, Outeniqua, Dolobran, North Lodge, the Stonehouse, the Moot House, the Pines. These were the grand mansions of the city threatened with demolition. Flo Bird thundered: "Yes, Parktown feels strongly about its heritage. We lost so much of it to the College of Education, to the Hospital and to the M1. If you look at Helen Aron, Shirley Zar and Clive Chipkin’s book on Parktown you can understand how much has gone and why we fought and still fight to preserve it. But the Parktown plaques have all been paid for by sponsors and later by the owners.”

However, the PWHT also realized that public support could be encouraged and promoted through stimulating interest in popular history and a hundred years later, the Anglo Boer war fell into the heritage tourism category. A wonderful walking trail marking the Anglo Boer War centenary, 1899-02, shaped a route and a series of plaques. Flo Bird, Den Adams and Elaine Persona took their blue plaque campaign through the suburban streets and then produced an excellent pocket size book of the trail - Follow the Flag.

Early days for of the Parktown and Westcliff Heritage Trust. Den Adams, Flo Bird and Elaine Persona installing the Doveton road Plaque in the 1980s (The Star)

As mentioned, the first plaques were made of metal (not feasible as many of these were stolen). Then came ceramic plaques (fragile and could break) and more recently there has been a switch to fibreglass manufacture under the capable management of Magda Mostert.

In the last decade, the Johannesburg Heritage Foundation grew out of the Parktown and Westcliff Heritage Trust and since its establishment in 2013 this new body has embedded the blue plaque in Joburg’s culture. The JHF has promoted the blue plaque as a tactic of redress and reconciliation with new plaques adopted by Soweto residents in Orlando and Dube.

The Heritage Association of South Africa remains active and honoured Bishop Desmond Tutu with a blue plaque in Villakazi Street (home to two Nobel prize winners) in 2011. The City of Johannesburg has joined the JHF as partners in promoting and developing their own blue plaque 'Johannesburg City Heritage' series; this partnership is unusual as the blue plaque movement is entirely a citizens grass roots movement and not a government or state scheme. Nonetheless the blue plaque provides a platform for genuine cooperation between civil and municipal society. Recently the Johannesburg Development Agency has also come on board.

Desmond Tutu speaking at the blue plaque unveiling ceremony in 2011 (Kathy Munro)

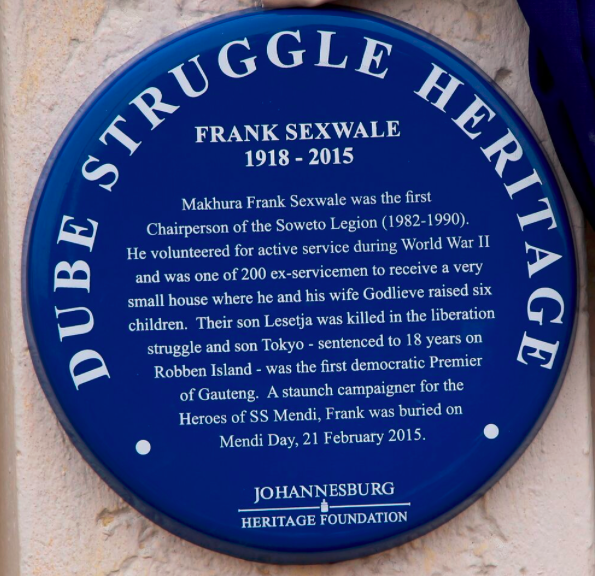

Blue plaques are not evenly spread around the City and the JHF now makes a budget allocation to stretch heritage conservation into previously neglected parts of the city and brings Johannesburg Heritage new enthusiasts. Blue plaques become a tourism opportunity and an imaginative tour may follow a trail around the blue plaques of a particular suburb be it Parktown West or Dube. The latest series is the Dube Struggle Heritage.

Frank Sexwale blue plaque part of the Dube Struggle Heritage series (Gail Wilson)

The blue plaque is a powerful heritage marker but it carries no legal status. The odd aspect to this blue plaque drive is that there is no law governing blue plaques. The award of a blue plaque signals that, in the opinion of the Johannesburg Heritage Foundation (or another civil society body), the particular place is worthy of remembrance and celebration. The blue plaque confers a noteworthy heritage status and is a subtle (and perhaps an obvious) signal to a developer or an owner that the particular property should be protected and should not be altered or destroyed, demolished or neglected.

Blue Plaques require the permission and support from the owner of a heritage property. The JHF wants to work with owners to ensure that they appreciate the significance of their properties and assume responsibility of the site's upkeep. Over the years blue plaques have survived and very few have been lost to wanton destruction but they do require some upkeep and cleaning. Over time materials used have changed but the look remains the same. Of course the JHF wants to celebrate heritage; sometimes the owner of a particular property sees a blue plaque as a marketing opportunity or a means of raising the value of a particular property in event of resale. In my opinion it is a matter of finding common ground and ensuring that the wording of the blue plaque captures historical facts accurately.

One odd heritage plaque that seems to have been a good idea that did not gel into a series of plaques but stands outside the blue plaque movement was the silver plaque of the Kensington Club, in Ivanhoe Street, Kensington, sponsored by Kensington Heritage.

Kensington's silver plaque

There is a challenge to picking the sites for blue plaques, preparing a motivation for the JHF and then once the organisation gives the go-ahead, raising the money to fund the blue plaque (private funding where possible and available, fundraising where necessary or drawing on the small JHF budget if the Foundation considers the plaque promotes neglected history in a less affluent part of town).

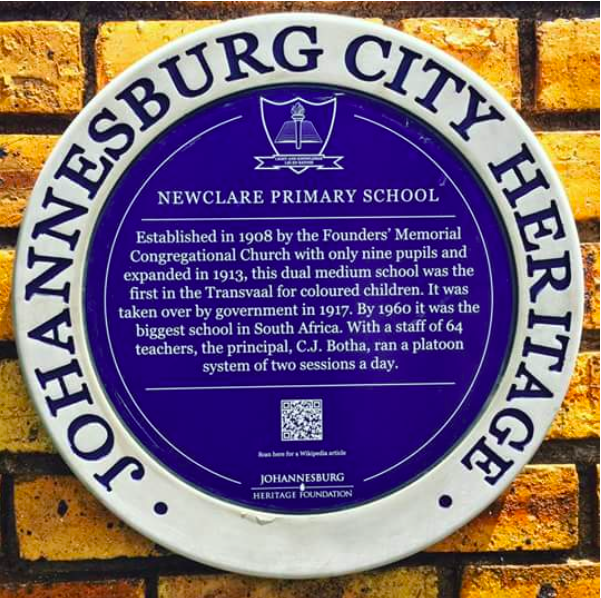

Newclare Primary School blue plaque (Johannesburg Heritage Foundation)

In recent years the JHF has arguably become the biggest promoter of the blue plaque movement in Johannesburg. In many cases the organisation works with the City's Heritage Department under Eric Itzkin to identify sites worth plaquing. Eric has been involved for about 12 years. The Johannesburg Development Agency has also become a keen supporter of blue plaques.

Blue plaques present a tourism opportunity and we would like the City’s Red Tour Buses to point out the blue plaques on their various routes. Ideally a city blue plaque route could tell the history of the city in a series of strategically placed blue plaques. The top of the red bus is a great vantage point for a blue plaque spotting adventure.

Once we have a blue plaque installed it then needs to be slotted into a register and its existence recorded. The City of Johannesburg maintains one register and the Johannesburg Heritage Foundation has another positioned on its website. The Heritage Register maintained by James Ball is another form of documentation with a note and electronic link as to whether a particular heritage site has a blue plaque and what information has been recorded. Ideally each blue plaque should be photographed and the date of installation recorded.

James Ball also initiated a unique website reaching further afield called BPSA (Blue Plaques of South Africa). This online resource ambitiously aimed to record all Blue Plaques in South Africa. Unfortunately it has been put into hibernation for the time being due to time constraints. It would be wonderful if it could be resuscitated and ideally this should be a project of HASA.

BPSA logo

The newly formed Magaliesberg Association for Culture & Heritage (MACH), following the lead of the JHF and enthused by the talk I delivered in 2017 has taken up the blue plaque concept and recently installed 5 blue plaques at the Paul Kruger farm, Boekenhoutfontein, under the auspices of Kedar Lodge. Several more blue plaques mark Anglo Boer War battles and skirmishes in the North West. MACH has taken the initiative of awarding a blue plaque authorization certificate to the owner of a site.

Five recent blue plaques installed at Kedar Lodge / Boekenhoutfontein (Kathy Munro)

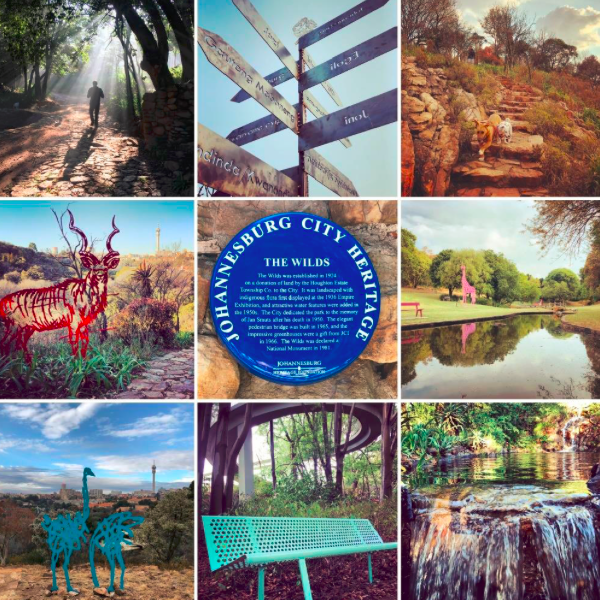

One of the most recent of Johannesburg Heritage's initiatives has been the Wilds Project working with James Delaney. A blue plaque has gone up in the Wilds and a Centenary Gate is being planned. Another linked initiative is to mark the centenary of Munro Drive with its favourite panoramic view site. Here the JHF is working with the Lower Houghton Residents Association with the active engagement of Colin and Mel Wasserfell.

Montage of The Wilds (Brett McDougall)

A delightful project that combined the blue plaque and a city map in mosaic format was the JDA sponsored End Street Beacon with an Andrew Lindsay Mosaic of the original map of Randeslaagte triangle done in a mosaic and at each end of the triangle a Randjeslaagte Beacon blue plaque.

The blue plaque idea is an international one and handled differently in different parts of the world. The idea of the blue plaque originated in 1866 in London, initiated by the Royal Society of Arts and is thought to be the oldest in its kind in the world. The second custodian was the London County Council and most recently English Heritage have run the London Blue Plaques programme since 1986 and their idea is to “link the people of the past with the buildings of the present“. There are over 900 blue plaques in London today. English Heritage's focus is strictly London but elsewhere in the UK other cities and towns have their own heritage plaque schemes. Manchester, for example, uses different colours (blue, red, black and green) to commemorate people, events, buildings and an amorphous “other”. London blue plaques insist on a person being deceased for at least 20 years before awarding him a blue plaque and their normal rule is that there is only one blue plaque for each past hero (Gandhi though has two).

I searched for London blue plaques with a South African connection and found that Cetshwayo, Sol Plaatje, Olive Schreiner, Mahatma Gandhi and Joe Slovo and his wife Ruth First are all remembered in London blue plaques. Nelson Mandela unveiled the Joe Slovo plaque. The wording of a London blue plaque states very simply name, dates, author and lived here in a specific year. The ANC‘s London Headquarters (1978-1994) is remembered in the London Borough of Islington in a green plaque. My particular London blue plaque favourites are Fabian Ware, John Lennon, George Orwell, Winston Churchill, John Constable, T S Eliott and Alan Turing - a diverse blue sea of fame on the streets of the city.

Blue plaques or their variant will also be found in Canada. There is a Heritage Building series in the City of Vancouver. I spotted blue oval plaques in Melbourne Australia and in Australia it seems that a Heritage Register is published and any member of the public is invited to erect and finance a blue plaque selected from this official heritage list.

In South Africa we stretch our history more widely as we go beyond people and include architecture, buildings and homes of note, events, historical themes and more. It is a direct link between past and present. Blue plaques can promote a far more inclusive history in our fractured society. A new blue plaque series is the Dube Struggle history series unveiled in Black History month. A novel idea captured in a blue plaque has been the blue plaque on Oxford Road marking an old beacon. A new blue plaque will honour Trevor Huddleston at the Orlando Swimming Pool. We are also planning a blue plaque series for the Orange Grove Waterfall and for the Yeoville Water Tower and surrounding classic apartment blocks.

Eric Itzkin speaking at the unveiling of the Dube Struggle Heritage blue plaques (Gail Wilson)

Oxford Road Beacon (The Heritage Portal)

There is an art in writing an inscription of a blue plaque. 100 words challenges the historian and wordsmith to get to the essence of what the blue plaque is about and why it is there. Names, dates, event and significance have to be condensed. Research is required, followed by fact checking and review. Sometimes we get it wrong (mistakes can be expensive) but we also have to be responsive, sensitive and receptive to criticisms. Sometimes blue plaques are damaged when a building falls into decay and disrepair.

In 2016 the JHF broke new ground with the unusual decision to award a blue plaque for a fine work of modern architecture, a prize winning home in Forest Town, Johannesburg. The house is only 30 years old. That decision was keenly debated.

Flo Bird welcomes the drive to plaque Johannesburg and commented: “If people feel their area is under-represented then they can start doing some of the leg work. Getting the funding helps immeasurably, checking the wording is time consuming and sometimes it is almost impossible to find impeccable sources. Lots of people claim their house is the original farmhouse, yet can produce no proof. Lots claim their house is a Baker, but if they do so we actually can check because we have access to the records. We try to ensure that all information contained on a blue plaque is accurate and verifiable.”

The plaque concept can also be a device to name and shame an owner to act on neglect and destruction and to draw attention to failed buildings. In 2017 Flo Bird initiated an idea of temporary cardboard black plaques to go onto selected disastrous buildings which ought to have been celebrated with a blue plaque. This was a team effort of the Gauteng Heritage Action Group. I am all for marking illegal demolition and destruction with a plaque that names and shames those who treat previous heritage in a cavalier manner.

One of the black plaques

Perhaps there is space for humour and a little fun in the plaque idea – why not pink plaques or green plaques for champion trees, red plaques for transport history etc. There are many opportunities and possibilities - the only limiting constraint is our own mindsets. With the recent frequency of fire and arson in the city we need to come up with a way of telling the destroyers of heritage that the city has a voice and we want heritage protected.

Sources:

- Guidebook to Sites of Geological and Mining Interest on the Central Witwatersrand, edited by F Mendelsohn and C T Potgieter. The Geological Society of South Africa in association with the South African Institute of Mining and Metallurgy. 1986

- Telephonic interview with Herbert Prins 2019

- Personal correspondence, Flo Bird to Kathy Munro

- Field visits to view Jhb blue plaques

- JHF review and planning documents

- JHF website , lists of Blue Plaues

- James Ball Heritage Register

Kathy Munro is an Honorary Associate Professor in the School of Architecture and Planning at the University of the Witwatersrand. She enjoyed a long career as an academic and in management at Wits University. She trained as an economic historian. She is an enthusiastic book person and has built her own somewhat eclectic book collection over 40 years. Her interests cover Africana, Johannesburg history, history, art history, travel, business and banking histories. She researches and writes on historical architecture and heritage matters. She is a member of the Board of the Johannesburg Heritage Foundation and is a docent at the Wits Arts Museum. She is currently working on a couple of projects on Johannesburg architects and is researching South African architects, war cemeteries and memorials. Kathy is a member of the online book community the Library thing and recommends this cataloging website and worldwide network as a book lover's haven.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.