Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

If a pioneering contractor, in the popular image, was big, bold, blustering and boozy, then George Pauling fitted the bill. He was an enormous man who stood back for nobody, but his reputation as the leading railway contractor in the development of Southern Africa during the late 19th century was only partly due to his physical presence. His success was mainly based on shrewdness, common sense and a huge capacity for hard work – and, it may be said, a talent for making friends in the right places.

George Pauling

Pauling was born in 1854 in India, where his father Richard was Resident Engineer on the Delhi Railways. He came from a family whose construction connections stretched back to Elizabethan times – an ancestor reputedly worked for Wren on the dome of St Paul's Cathedral, while another built the British Museum. The elder Pauling appears to have been somewhat erratic, and at the age of 15 George was forced to contribute to the family finances by taking a job with Firbanks, a well-known firm of railway contractors. It was a tough introduction to the working world, but young George gradually worked his way up to the position of timekeeper, where his dealings with the navvies taught him a lot about handling labour in the construction industry. He caught the eye of a member of the Firbank family, and by the age of 18 was promoted to office manager and measurer on a tunnel contract. His pay was still less than £2 per week.

In 1875 he and his brother emigrated to South Africa, where a great-uncle, Henry Pauling, was the resident engineer on railway construction at Wolseley. The brother, Harry, was employed there, but possibly because three Paulings would have been too much at one spot, George was sent to the Eastern Cape to work on one of the tricky tunnels on the Alicedale - Grahamstown route. He quickly realised that it would be preferable to work for himself than for the Cape Government Railways, and he resigned and completed the project as a contractor. He formed an alliance with his old firm, Firbanks, to tender for the Kowie railway, and having completed that contract successfully, never looked back.

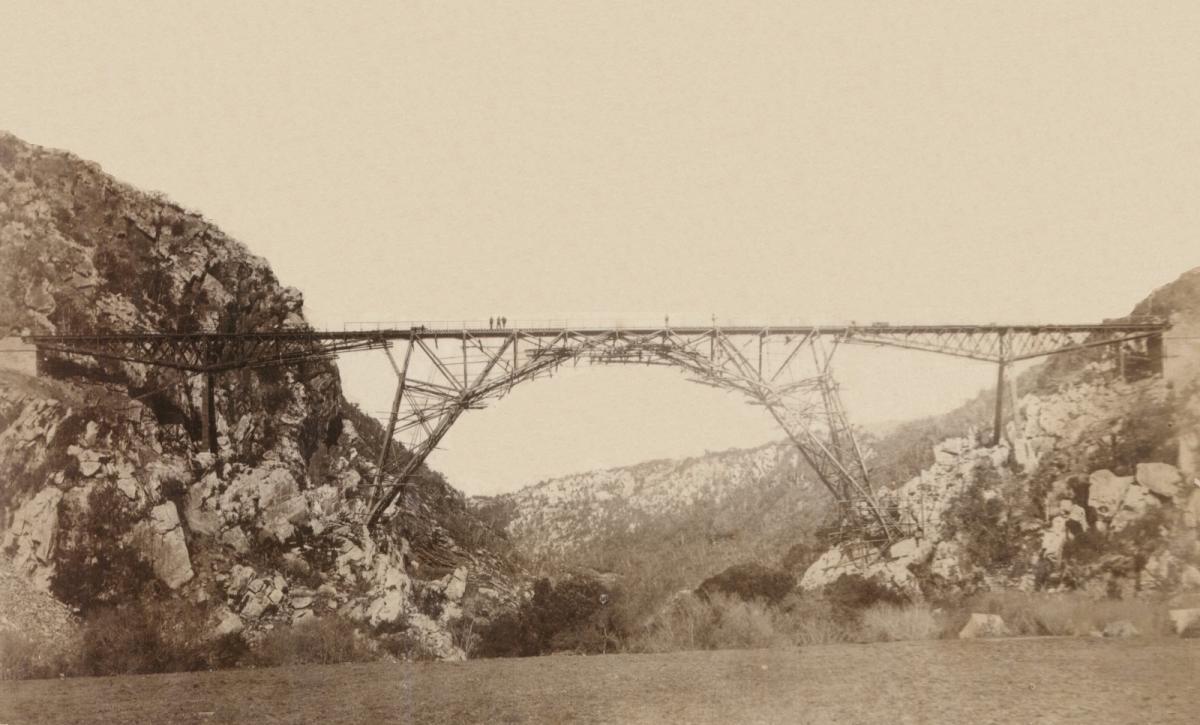

The Blaauwkrantz Bridge on the Kowie line

He had other strings to his bow besides contracting, and while in Grahamstown acquired a newspaper, an ostrich farm, and for a time was landlord of the Masonic Hotel. Here he was known to entertain guests by carrying his Basuto pony around on his back; he gave up the trick when he injured himself trying to carry it upstairs.

His first big contract was to complete the rail line from the Orange River to Kimberley. During the job he came across the well-known problem of the client who tried to increase the scope of the contract without compensating the contractor. The contract ended suddenly when the junior official who was causing the problem was sent sprawling by a punch from Pauling's fit, extra-heavyweight frame. Pauling lost money but learned a lot.

The line reached its planned end in Kimberley in November 1885 amidst great celebrations.

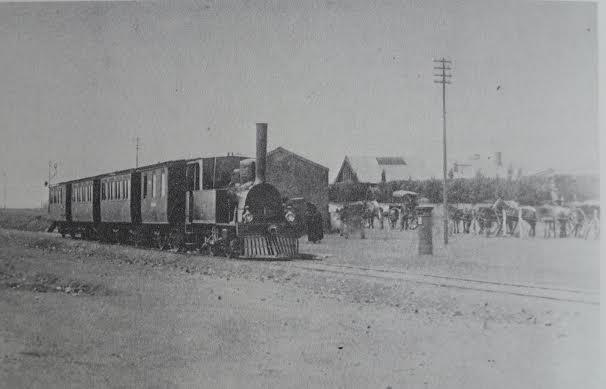

Arrival of the first train in Kimberley

His sojourn on the diamond fields had introduced Pauling to the mining fraternity and he tried some speculation in gold in Barberton and Johannesburg. Along the way he met Cecil Rhodes, and the two must have seen complementary energies in each other. The mining ventures put him in touch with the French bankers d'Erlangers who became the chief financiers of his construction ventures.

While in the region he became involved in the construction of a railway from Boksburg to Johannesburg, which to placate some ultra-conservative old Transvalers had to be called a "tramway', and thus the "Rand Tram" was born - a railway in all but name. He was introduced to President Kruger, who thereupon arranged for him to complete the railway through Crocodile Poort when the original Dutch contractors failed.

The Rand Tram (Seventy Golden Years)

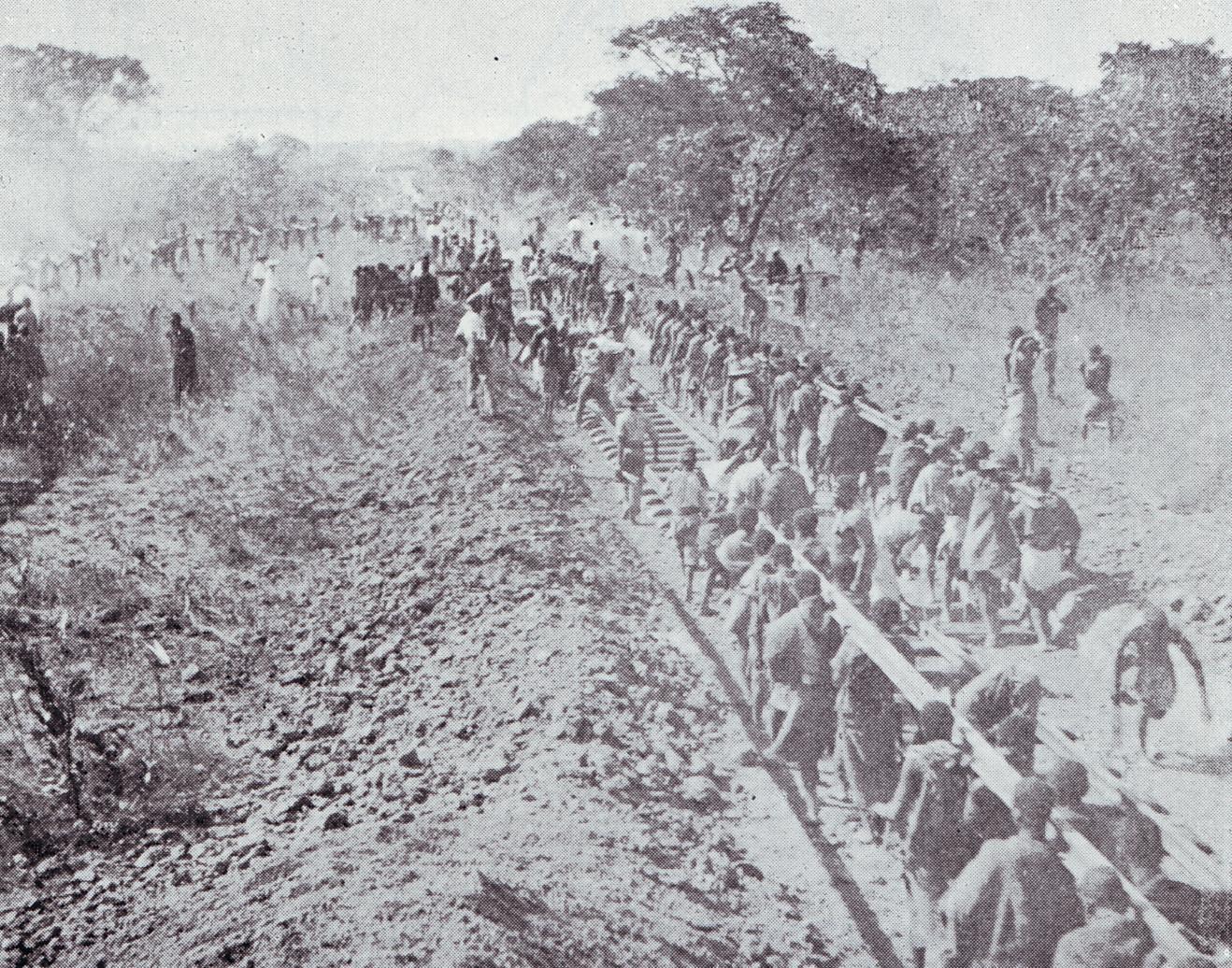

After completing contracts to connect Kimberley with Mafeking, Pauling was earmarked by Rhodes as the man who could bring his great plan of a Cape to Cairo railway to fruition. He engaged him to build the line to from Mafeking to Bulawayo, on condition that the last 400 miles of track were laid in 400 days. By a great feat of project management, this was duly accomplished and Pauling was thereafter in Rhodes's first team.

An even more daunting project was to build the line to link Rhodesia to the port of Beira through the fearsome fever belt of the Mozambique coast. The alignment was difficult, and on Pauling's suggestion the entire village of Umtali was demolished and re-erected nine miles away to suit the preferred route. But the fever took its toll, and a great many European workers, including his brother Harry perished from malaria, and other unfortunates were taken by lions. Pauling maintained that teetotallers were bound to perish from the dreaded malaria and attributes his survival to the liberal intake of whisky. He had a phenomenal capacity for liquor and on one forty-eight hour trip up the Beira railway, he and two companions put paid to three hundred bottles of German beer.

For a while Pauling acted as Minister of Mines and Commissioner of Public Works in the fledgling Rhodesia, and he also took on the job of Postmaster-General. He led a Pooh-Bah existence - any complainants were referred from one office to the other, and while the parties were waiting for an appointment with the next official, Pauling took them for drinks - after which the complaints were lost in an alcoholic mist.

Meanwhile the railway work in Central Africa forged ahead. On Rhodes's instructions Pauling located the bridge across the Zambezi at the Victoria Falls "close enough for the spray to wet it" - and was then furious when he failed to land the construction contract. In the end he was probably mollified because the Cleveland Bridge Company lost a considerable sum on the job.

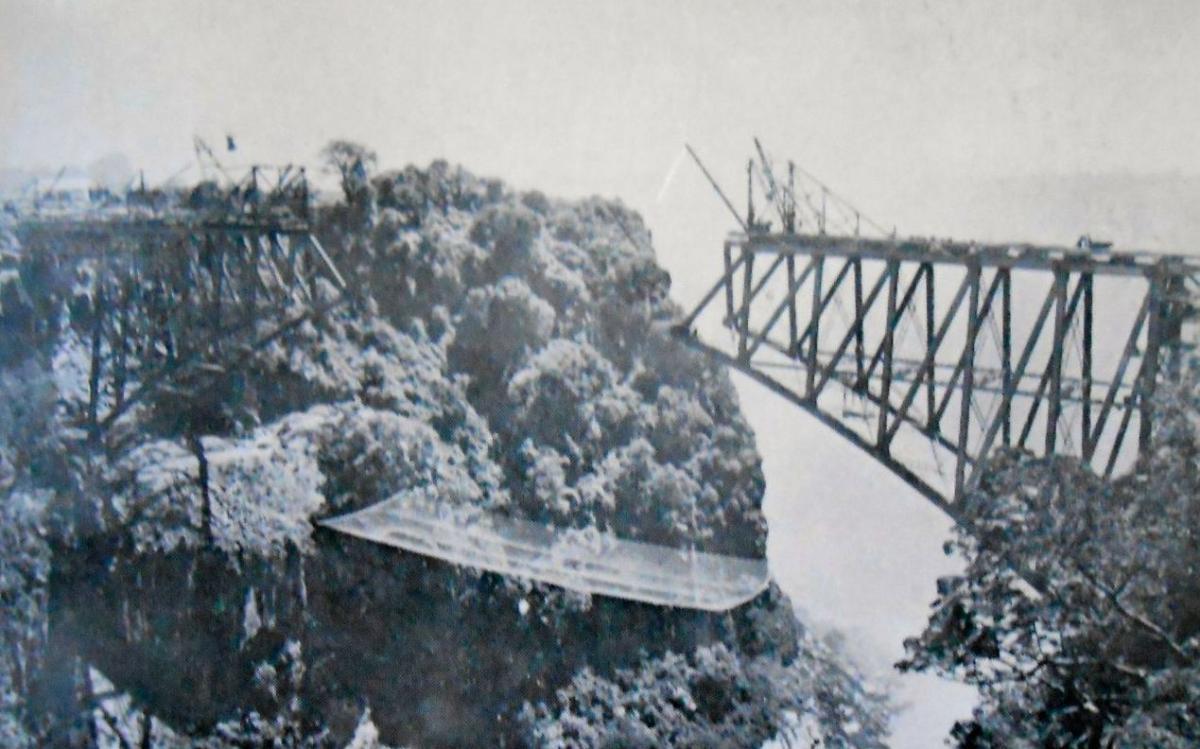

Victoria Falls Bridge under construction

While the bridge was under construction he carried on with the line on the northern side of the river, conveying all the material across the gorge by cableway. Thousands of tons were transported in this way, including locomotives which were knocked down and carried across piece by piece, reassembled, and then used to ferry material to the head of construction. The rail network moved forward through the then Northern Rhodesia and made it possible for the Copperbelt to be developed and become an economic asset. Overall Pauling and Company was responsible for constructing over 1500 miles of the Cape to Cairo Railway during the period 1893 to 1910.

By this stage the Pauling Company had gained a world-wide reputation, and apart from further work in South Africa, including the Selati railway in the Lowveld and the line up Sir Lowry's Pass to Caledon, there were ventures in Palestine, Borneo, India, China, Argentina, Greece, and a substantial amount of work in England. He continued to pick up relatively minor contracts in South Africa, and his final major work was the fearsome Benguella Railway between the Copperbelt and the Atlantic.

George Pauling retired to his mansion in Surrey in 1915, and became a genial host and public benefactor - a far cry from his rumbustious days in Africa. Surprisingly, he wrote an autobiography - which in modern times would probably have been "ghosted". But this was his own work and is eminently readable.

He died in 1919. By any standards he was a giant among contractors.

Book Cover

Tony Murray is a retired civil engineer who has developed an interest in local engineering history. He spent most of his career with the Divisional Council of the Cape and its successors, and ended in charge of the Engineering Department of the Cape Metropolitan Council. He has written extensively on various aspects of his profession, and became the first chairman of the History and Heritage Panel of the South African Institution of Civil Engineering. Among other achievements he was responsible for persuading the American Society of Civil Engineers to award International Engineering Heritage Landmark status to the Woodhead dam on Table Mountain and the Lighthouse at Cape Agulhas. After serving for 10 years on SAICE Executive Board, in 2010 he received the rare honour of being made an Honorary Fellow of the Institution. Tony has written manuals, prepared lectures and developed extensive PowerPoint presentations on ways in which the relationship between municipal councillors and engineers can be more effective, and he has presented the course around the country. He has been a popular lecturer at UCT Summer School and has presented five series of talks about engineers and their achievements. He was President of the Owl Club in 2011. His book "Ninham Shand – the Man, the Practice", the story of the well-known consulting engineer and the company he founded, was published in 2010. In 2015 “Megastructures and Masterminds”, stories of some South African civil engineers and their achievements was written for the general public and appeared on the shelves of good bookstores. “Past Masters” a collection of his articles about 19th century South African Engineers is also available from the SAICE Bookshop.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.