Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

Port Nolloth is a sleepy town located on South Africa's north western coast. Today it is a great spot for a relaxing seaside holiday but life in the town was not always so easy. In the book A History of Copper Mining in Namaqualand John M Smalberger digs into the early history of the town and describes the incredibly tough conditions experienced by those brave enough to live there.

Before the commencement of copper mining, Robbe Bay, as Port Nolloth was then known, was important in so far as it provided the Namaqua with a source of income from the sale of seal skins, and as a source of food, since the seal meat was dried and could annually support some 300 persons. With the advent of mining it assumed, for a short time, a greater significance as one of two harbours used for the export of copper ore and, more importantly, for the import of food and capital equipment. Despite its advantages over Hondeklip Bay, mainly in that it possessed an inner anchorage which was safe ‘in any weather whatsoever’, Hondeklip Bay came to assume the position of port for Namaqualand to the exclusion of Port Nolloth. This was the result of a number of factors; the early closing of the northern ‘mines’ after the copper mania of 1854/55; the fact that the Port Nolloth route was badly circumstanced for water; and that the Hondeklip Bay route was closer to the homes of the majority of transport riders. It must also be borne in mind that there was a fairly large establishment at Hondeklip Bay and that Phillips & King, the major producers of copper ore, owned most of the farms en route to Hondeklip Bay. These capital investments would obviously not be abandoned lightly. In any event, by 1856 there were only two or three residents at Port Nolloth, and even as late as 1864 it remained a settlement consisting only of some four or five wooden houses.

Sketch of Hondeklip Bay 1854

In 1865 a controversy arose over the choice of the future port of export for Namaqualand, but in the end it was decided to retain Hondeklip Bay as the chief port and construction of a new road was begun. This road was never completed as The Cape Copper Mining Company eventually decided to accept the recommendations of the engineer brought out by them to undertake surveys of the possible roads. They obtained permission in 1869 for the construction of a line of rail from Port Nolloth to Muishondfontein.

Almost immediately, Port Nolloth, which until then had consisted only of the stores of Mr F. W. Dreyer, a trader, began to grow apace. Even prior to this it had become increasingly important as a port for shipment. In order to obtain the benefit of a customs officer at the port, The Cape Copper Mining Company undertook to pay £200 a year as a salary and to provide quarters for such an officer.

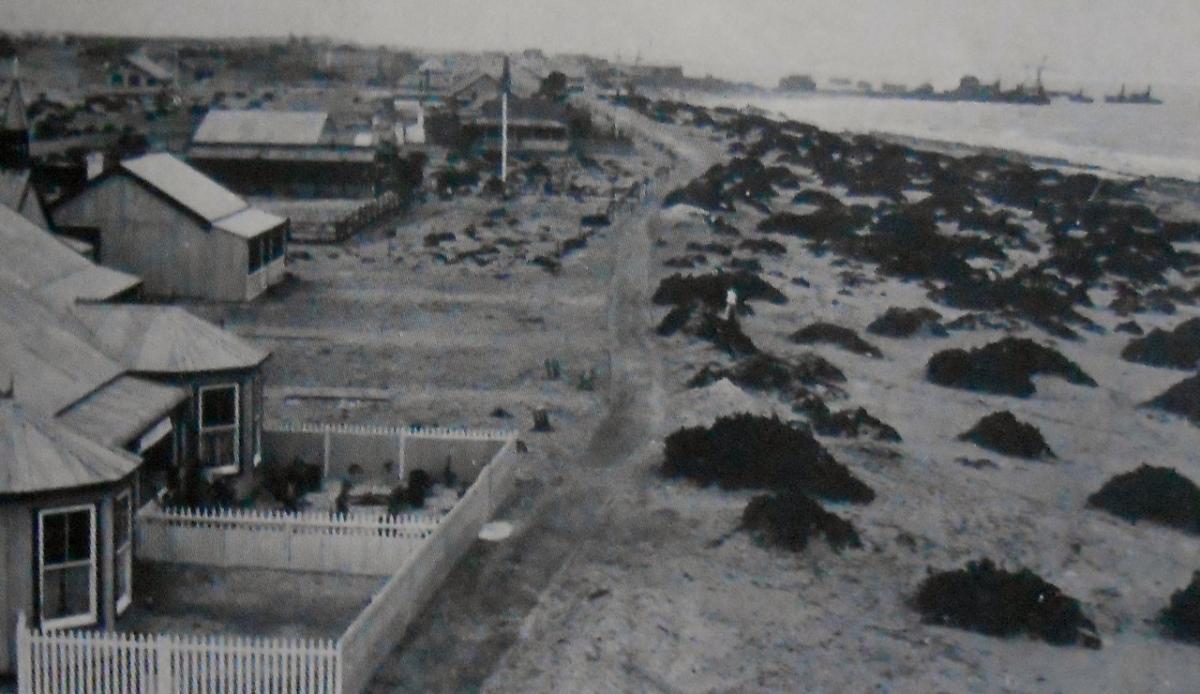

Port Nolloth from the lighthouse looking South c1905

By 1872 the port had grown somewhat, though its appearance left much to be desired. In 1874 Port Nolloth was created a separate magisterial district. By this time a great deal had been done to improve the handling and shipping or ores, a jetty had been built out some 300 feet in length, carried to a depth of 11 feet at low-water and there was suitable wharfage accommodation and stores for carrying on a large trade. Moorings had been laid down and beacons and a light for the guidance of vessels had been put up. But while there had been considerable improvement of facilities, the lot of its inhabitants was not to be envied.

Port Nolloth jetty showing method of loading copper ore

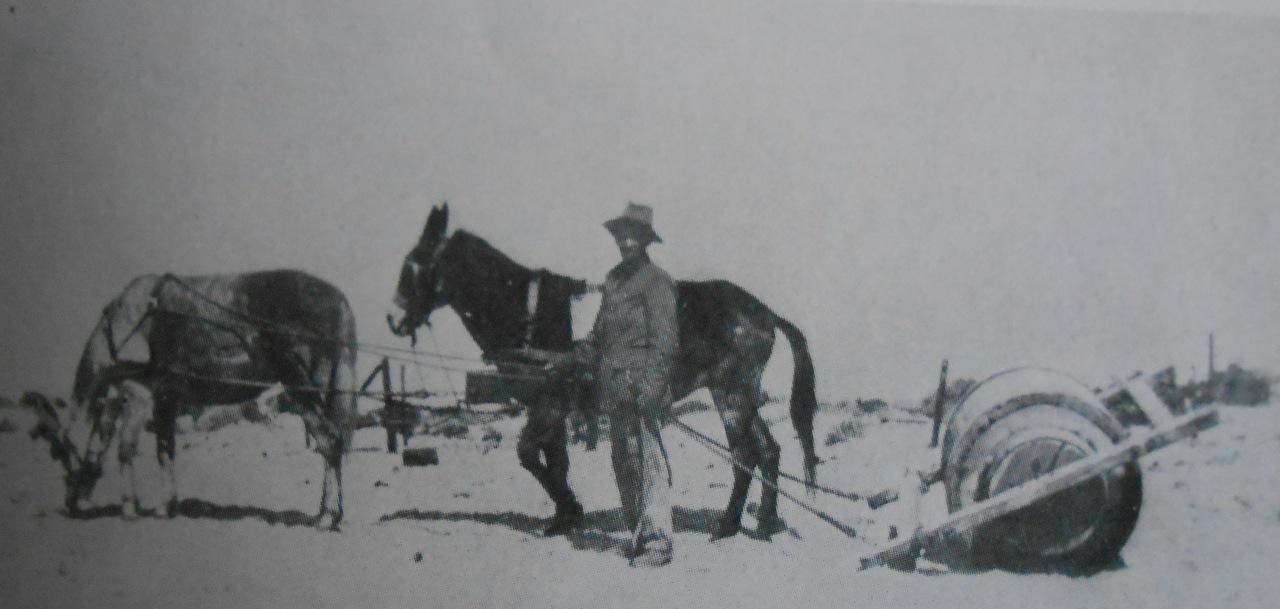

About once a fortnight a little steamer called from Cape Town bringing the necessities of life. Water for settlement was obtained from a place called Jules Hoogte, about five miles from the port, and was distributed by ‘rol-vaatjie’.

Rol-vaatjie Port Nolloth

The port grew rapidly: thus while there had been only 300 inhabitants in 1872 and 448 by 1875, by 1882 there were about 2000 inhabitants. The appearance of the place had not, however, improved and Simon, later Bishop for the Hottentots, and his fellow travellers received a rude shock when they first saw the ‘city’ of Port Nolloth from the decks of the Namaqua, the Union Company’s steamer which plied the Cape Town-Port Nolloth route.

Port Nolloth from the jetty c1880

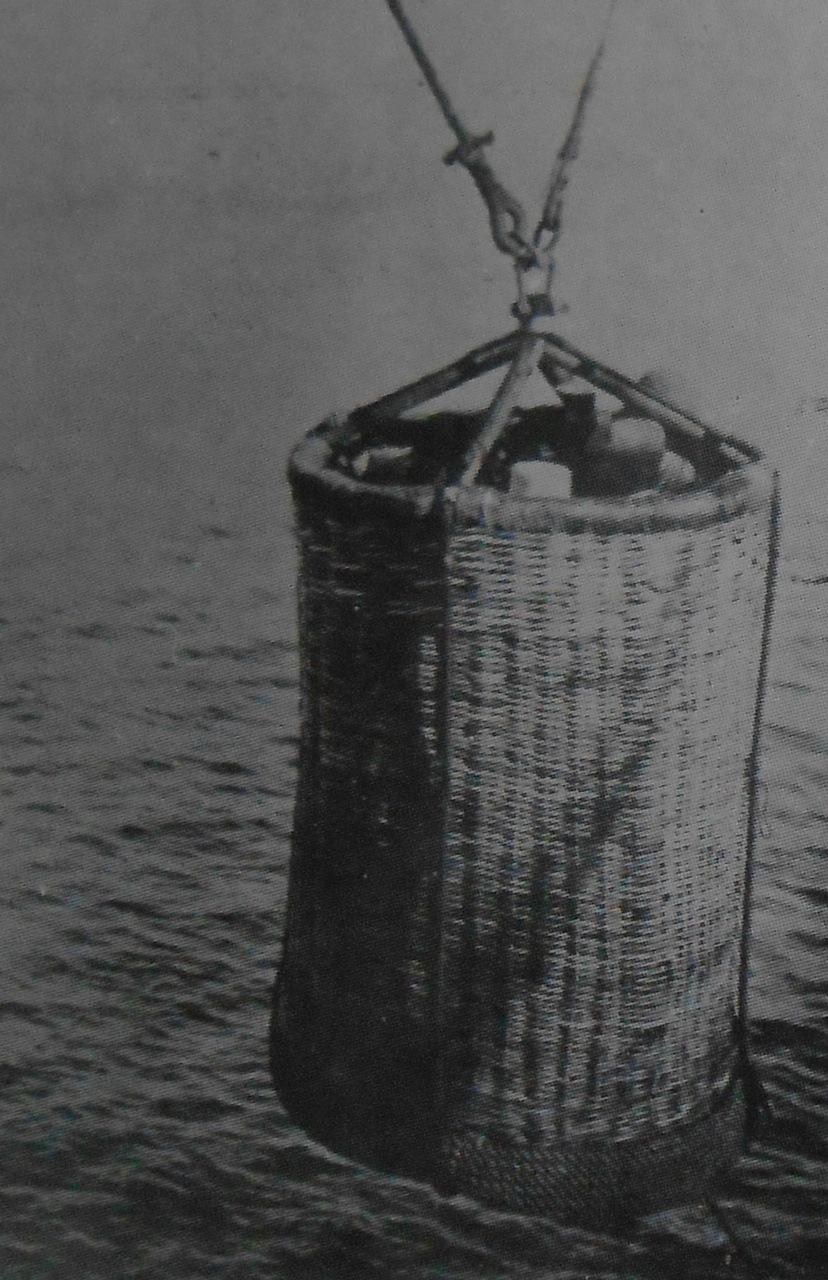

An even ruder shock awaited them on approaching the pier. How, they wondered, was one to get from the boat to the wharf? For those who were still nimble and who had done gymnastics in their youth there was apparently no problem since they merely clambered up an almost perpendicular ladder; for the older, Africa’s inventive genius provided a cylindrical basket about five feet high which had an exit in the side and which was lowered to the boat by means of a chain and pulley. This adventurous mode of disembarkation is vividly described by Simon:

Ladies and gentlemen, enter! A whistle set the donkey engine going and you were raised up and swung in the air. Your head was swimming, you screamed. No one paid attention to you. You continued your ascent, and when the time came the derrick transmitted its churning motion to you and deposited you less delicately upon the landing. Deo gratius! We had arrived safe and sound at our mission.

Basket used for raising passengers to the pier at Port Nolloth

In 1886 W. C. Scully arrived at Port Nolloth aboard the Namaqua to take up his appointment as Relieving Magistrate and Civil Commissioner of Namaqualand. He did not consider Port Nolloth the most appealing place:

Port Nolloth is a dreary and God-forgotten looking spot. Nautically, it is an open roadstead, with a narrow channel blasted through a reef of rocks, admitting small vessels in calm weather to a sort of pond. There is a lighthouse, which can only be useful a a signboard telling ‘this is Port Nolloth’ as the spot where it stands is not more to be avoided than other wicked looking and storm-smashed rocks around.

But if Port Nolloth was not altogether prepossessing in its appearance, then there were at least many good and kindly inhabitants living there who entertained most hospitably. The village too, boasted its own newspaper, The Port Nolloth Times, printed for private circulation. Port Nolloth also boasted a cricket club - the ‘Hope Cricket Club’ By 1896 some improvements had taken place. A proper sanitary system was established and the cemetery which had become nearly obliterated by sand had been cleared. All in all, the witnesses of the last century are in agreement concerning the unpleasant site of Port Nolloth, when viewed from the sea or land, and in 1902 we have further testimony to the ‘festering eyesore’.

By the 1930s Port Nolloth presented an even more dreary and poverty-stricken appearance. Carel Birkby found the poverty indescribable, exemplified to him by the idea of children begging for a drink of fresh water. By this time too, the houses already described in 1927 as rusting away must have presented a dreary appearance. These houses had actually been valued by The American Metals Company’s engineer at the ridiculous sum of 1s each, a sum he only agreed to because it was considered that, as they were occupied, some value ought to be given to them.

Port Nolloth Civic Centre, looking North c 1905

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.