Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

In May 1900, Lord Roberts of Kandahar, Commander-in-Chief of the British Forces, was poised to culminate his illustrious military career by marching triumphantly into his enemy’s capital city and concluding the South African War. But it was a charade. There could be no victory without a vanquished foe and the Boer leaders were still at large with a fighting remnant of their army. Another two bitter years of warfare lay ahead.

Lord Roberts (National Library of Ireland)

In the city, rumours were rife and the people awaiting the British advance lacked information and were desperately worried and afraid. Morale was at its lowest. Bessie Collins, a loyal republican despite her English surname, kept a daily letter-diary addressed to her friend in Port Elizabeth. On 6 May: “We all feel that we are very near the end. One more stand and all will be over. Our hearts are heavy. We fear the worst. The men are so weary and faint hearted that we do not even know whether their officers will get them to make a last stand.” Her concerns were probably echoed by many in the town when a week later she recorded: “I cannot see the use of shedding more blood and only long for this awful war to cease. It is getting unendurable to sit here day after day and wait for those English to come.” On 20 May: “Oh! the misery of this suspense. We just live a day at a time and never know what will become of us. We may be ordered out to laager any day.” Private transport – wagons, carts, most horses and even some bicycles – had been commandeered by Kruger’s government and the fear that women and children would be forced to simply flee into the veld was a persistent theme.

Many shops and businesses in the town were run by British citizens. Most had left at the outbreak of war and their stock had been commandeered and transferred to the government stores on the corner of Church and Visage Streets. Those British who remained, did so under restrictive conditions and the constant threat of expulsion. As Lord Roberts came closer, antagonism and suspicion of conspiracy grew and so, for different reasons, they also suffered stress and anxiety. Mrs TJ Rodda, wife of an English store manager, wrote, “no one can in the least enter into the feelings of those who went through [those times]; the sleepless hours, the strain and the heartache and ... of indignities best left untold.”

While the citizens of Pretoria grew incessantly more desperate, President Paul Kruger remained uncommunicative, and his silence intensified the suspense. The British thought that the Boers would defend Pretoria – four large forts had been built around the outer limits of the town for this very eventuality – but the big guns had been removed and taken to the front months before, and most people knew that any stand would be futile.

In fact, the government had secretly decided on 9 May that the town would not be defended. In the words of Jan Smuts, the Attorney General, “…the hope of those who saw farthest and thought deepest was not in the fortified town but on the illimitable veld.” The Boer authorities had also decided to move the seat of government to Machadodorp and after dark on the night of 29 May, Kruger slipped secretly out of town. To avoid detection, he took a Cape cart as far Koedoespoort Station (then on the outskirts of the town) where he boarded an awaiting train.

Paul Kruger (Seventy Golden Years)

All this was kept secret to prevent the British from occupying Pretoria immediately but, when the townsfolk discovered the deception, they were outraged. An angry Betty Collins wrote, “Yesterday Pretoria woke to find that its government had gone and left us all in the lurch…To say the feelings of the people towards Oom Paul and the rest are bitter, does not in the least express it. All the gold has disappeared as well as the ammunition and a tremendous amount of food.”

With Kruger’s departure, the stoic resilience of Pretoria’s citizens began to crumble. Government servants had been given promissory notes in lieu of wages and when these were not honoured, they began to plunder the government stores on the corner of Market and Visagie Streets. Soon the looting spread to other shops and warehouses and for two days the streets were scenes of plunder and panic. Rumours that the British would commandeer all supplies stoked the mayhem.

To make matters worse, there was also confusion about who was in control. According to Smuts, he and Schalk Burger (who later became Acting President) had been appointed by Kruger to remain behind and maintain order. But Burger departed the day after Kruger, leaving a letter for the Mayor of Pretoria, Piet Potgieter, instructing him to take charge of the town and to surrender it to the British “in the event that our Burgers are unfortunately forced to retreat.” Potgieter tried to form a peacekeeping committee, later scornfully called the ‘Surrender Committee,’ but it had little public support and no control over the pillaging.

On the third day after Kruger had left, Commandant General Louis Botha arrived and declared martial law. Order was quickly restored, but his arrival had another even more serious purpose. On the night of 1 June, he and Generals, Koos de la Rey, Tobias Smuts, Sarel Oosthuizen, H.L. Lemmer, Ben Viljoen and several others met in the telegraph office on Church Square. Filled with despair they reached the painful decision to telegraph Kruger in Machadodorp and suggest that the war should be ended. Smuts explained their motivation: “The deplorable state of the Boer army; the certainty of an inglorious ending if the war was continued; the probability of the complete devastation of the country and the utter hopelessness of achieving any success.” Kruger agreed to put the suggestion to President Steyn of the Free State.

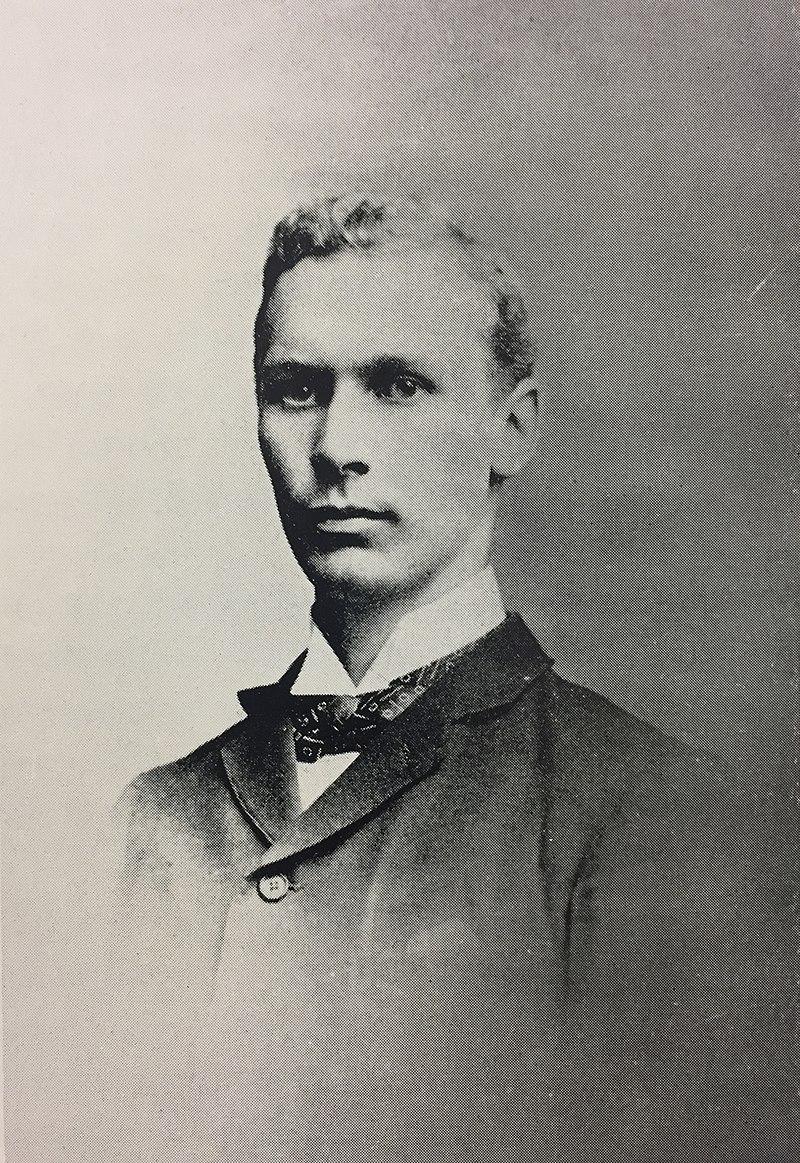

Jan Smuts (via Wikipedia)

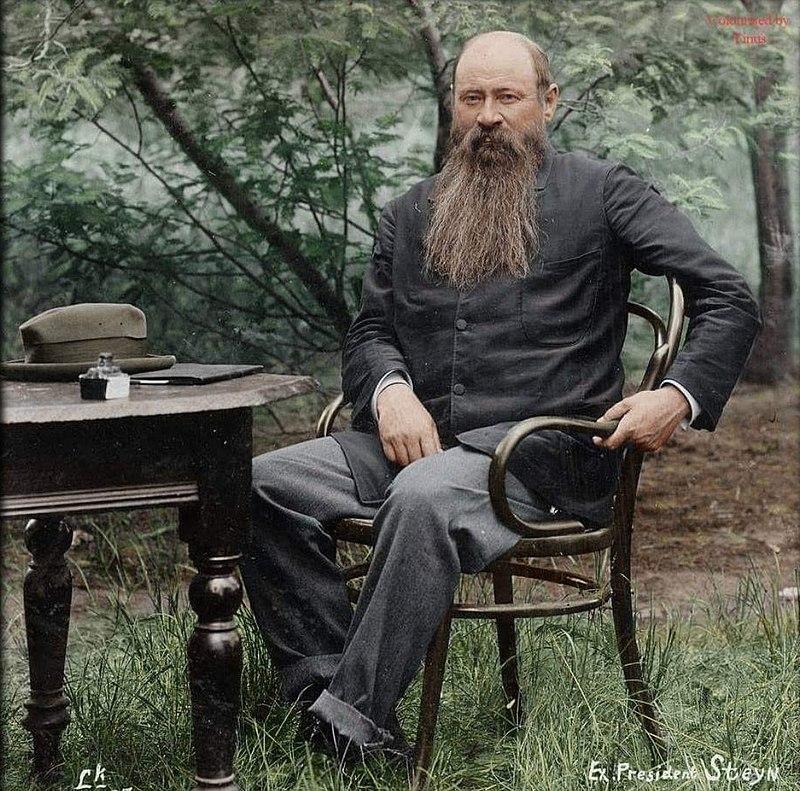

Steyn’s reaction was vitriolic! He condemned the generals’ attitude and virtually accused them of cowardice. His rebuke stung the Transvaalers deeply and the following day, they reversed their standpoint completely and decided to fight on. Their volte face was far more than just a change in strategy – it came to define the essence of Afrikanerdom. From that day on fighting to the bitter end, however futile and self-destructive, carried the badge of high patriotism; the views held by the generals the previous day, now bore the mark of treason. For another century, surrender (hensop) carried a stigma that stained whole families and seeped through generations. Two years later to the day, many of the same generals met on almost the same spot, confronting the same dilemma. But by then the price of Steyn’s persuasiveness had been paid. In Smuts’ words: “… two years more of war, the utter destruction of both Republics, losses in life and treasure ... Aye, but it meant that every Boer, every child to be born in South Africa, was to have a prouder self-respect and a more erect carriage before the nations of the world.”

President Steyn (via Wikipedia)

Another long-lasting but more trivial legacy was born that fateful week – the legend of ‘the Kruger millions.’ Smuts had been instructed to appropriate the gold reserves at the State Mint. Thomas Beckett, Chairman of the National Bank questioned Smuts’ authority and refused to hand over the gold. After a day of fruitless negotiation, Smuts threatened to have Beckett arrested and he yielded. Smuts seized between £400,000 and £500,000 of gold coin plus another £25,000 allocated to pay the salaries of government employees. Having found no one willing to take on the responsibility of paymaster, his memoirs record that, “… without compunction, I took this sum with me.” The total amount of less than half a million pounds funded the Boer war effort for the next two years compared with the British expenditure of £200 million. These facts were well explained at the time, and re-examined by countless historians since, but gullible folk, always preferring an improbable story to an obvious fact, continue to nurture the belief that Paul Kruger concealed millions of pounds sterling in a spot as yet undiscovered.

On the afternoon of 4 June, the British took what is now called Proclamation Hill after a brief skirmish. Lieutenant Watson, an Australian, was sent into town under a white flag to present Louis Botha with Lord Roberts’ demand for surrender. Botha requested a cease fire to allow the evacuation of women and children, but Roberts refused, and the Boer general left Pretoria to prepare for future conflict.

The next day Lord Roberts led a grand parade through Church square. Those loyal to Britain waved Union Jacks and Mrs Rodda dressed her children in red for the occasion, but for most townspeople there was little joy. One woman wrapped the Vierkleur around her hat in defiance of the parading soldiers and everywhere there was sullen antipathy towards the conquerors. Bessie Collins carried on diarising life in Pretoria until the end of the war. Her loyalty to the Boer cause never wavered but she and her neighbours longed for peace and had little sympathy with the bittereinder mindset. She even berated her future husband for not laying down his arms. Perhaps her views were more widely held that we are sometimes led to believe.

In writing this article I have relied heavily on two books by UNISA historian, Bridget Theron: Pretoria at War 1899-1900 and Dear Sue. The Letters of Bessie Collins from Pretoria during the Anglo-Boer War, both published by Protea Book House in 2000, as well as Jan Smuts Memoirs of the Boer War edited by SB Spies and Gail Natrass (Jonathan Ball, 1994) and S.B. Spies’s Methods of Barbarism (Human and Rousseau, 1976.)

Main image: War artist Melton Prior’s sketch of Lord Robert’s triumphal parade in Church Square on 5 June, 1900. A more widespread sentiment in Pretoria that day is probably shown by the disgruntled Boer in the left foreground.

About the author: Vincent Carruthers has written several books including The Magaliesberg (four editions), Cradle of Life (2019) and The Wildlife of Southern Africa (three editions). In 2006 he initiated the project to have the Magaliesberg region declared a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve. He has received awards from various institutions including the University of the Witwatersrand Gold Medal in 2016 and the North West University Chancellor’s Medal in 2013. He has been CEO of WESSA, chairman of Birdlife South Africa and member of the North West Parks and Tourism Board. Currently retired from his management consultancy, he is enjoying writing for the Magaliesberg Association for Culture and Heritage.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.