Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

Tiervlei on the outskirts of Cape Town is my hometown where my great-grandparents moved from Ceres during the 1930s. Six of my grandmother's children, including my mother, were born in Tiervlei, on the Northern Suburbs of Cape Town now known as Ravensmead. Apartheid has shattered our family; my great-grandparents as well as my grandmother lost properties in the process. My grandmother and mother were eventually forced to Belhar.

Initially, I researched my family history and was disappointed with how little of the history of Tiervlei, including the section later renamed Ravensmead, was recorded while a rich history lives in the memory of the seniors. This encouraged me to write about the history of the area from the perspective of the memory of my community, supplemented with other sources. This was my encounter with Hardekraaltjie, where loved ones and friends were laid to rest. The youth mostly went to the forest for wood or recreational activities close to the cemetery in the area where Stellenbosch University's Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences and Tygerberg Hospital is situated.

The article is dedicated to my Tiervlei and surrounding communities who do not know what happened to their loved ones who were buried in the cemetery. It is emotionally exhausting to realize how successive state institutions have neglected the cemetery and offended those buried here and their families. Our deceased were first placed in the forest, classified as the poorer coloured class and later marked and removed as unknown persons and eventually just removed to make way for a sports field.

The northern suburbs of Cape Town have a rich cultural history and heritage with several layers in its undefined historical urban landscape worthy of heritage conservation status. The former Hardekraaltje Outspan and forest reserve is one of these sites with many undiscovered layers. The focus of this article is the more than 100-year-old cemetery established for the "poorer coloured class" that was closed during 1947 and later sold for 10 cents. The old cemetery earmarked as a sports field is situated in the medical campus area bordering Tygerberg Hospital and the Transnet Railway Yard in Bellville.

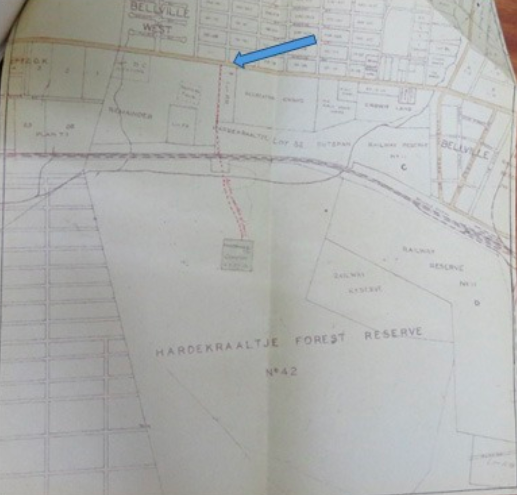

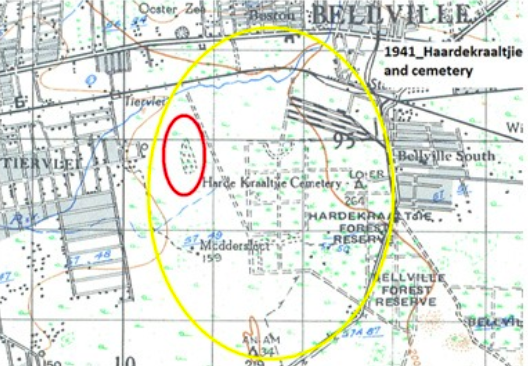

The cemetery in relation to the medical district and the Transnet railway yard.

The cemetery was an important place in the life of the community. The trustees, the Divisional Council and lastly the Parow municipality were responsible for the management of the cemetery and its sale to Stellenbosch University. The once isolated cemetery hidden in the forest caused tensions and an obstruction in the ongoing development of the area. This was the reason for its closure and sale to Stellenbosch University for property that was lost due to the expansion of the Tiervlei area and the South African Railways site.

I am arguing for the old cemetery to be restored as a place of remembrance of a past that was almost lost, that can be revived, for us and our descendants. It should be remembered in addition to the dehumanization of the "poorer coloured" by the Parow municipality. The municipality removed and classified the deceased as "unknown persons" hereby peeling away the identities of the community and families of the deceased from as far away as Kuilsriver, Bellville, Florida Estate, Stonehill, Tiervlei and Matroosfontein, as will be discussed. It is also reported that Stellenbosch University has removed bones, which is the subject of current investigations.

To access the isolated cemetery in the forest, you had to pass the well-maintained Outspan area, cross the railway line and the river while navigating the forest reserve. The history of the cemetery and who was buried there could have provided opportunities to understand how people perceived the past. Hayden (1995:9) sees identity as intimately linked to memory and mentions that urban landscapes are the storehouses of the social memories of families and communities.

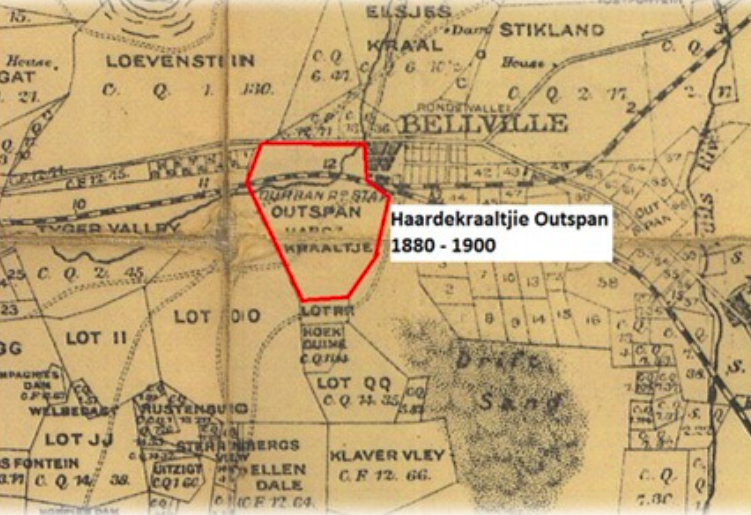

Map 1880-1890 SG Mapping for the area edited. The size of the former Hardekraaltjie Outspan.

The section where the current Hardekraaltjie caravan park is situated on the former "Hardepad", now Voortrekker Road, Bellville, is only a small part of where animals and travelers refreshed on the Hardekraaltje Outspan during the 1800s and 1900s. The rest of the forest reserve was densely forested and the cemetery was in this section.

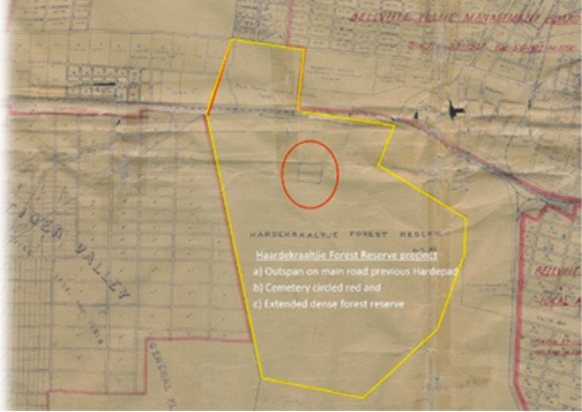

SG Mapping for the area edited. The size of the former Hardekraaltje Outspan.

Apartheid, development and urbanization destroyed the identity of the Hardekraaltjie Outspan and forest reserve. It also reduced the Outspan name, grazing, rest and social space to a "toe" of the footprint on the “Hardepad” side renamed Voortrekker Road, Bellville. The former Hardekraaltjie Outspan and forest reserve is largely developed, with the Transnet Railway Yard and Tygerberg Hospital owning the largest undeveloped portions.

Roders and Bandarin (2019:12) regard urban heritage as a collective creation. They believe successive societies gradually allow the expression of their culture in a shared space. These layers formed throughout history embedded literally and figuratively in the landscape is the evidence and significance which will conclude this paper’s submission in analyzing the significance and the consideration for heritage status for the site.

Hardkraaltje history

Geographically defined area

Hardekraaltjie was a historic Outspan, one of several resting places for animals and travelers who travelled to and from the Cape from the 18th century onwards. In August 1938, the Cape Divisional Council applied for the Grant Deed of six (6) Outspan’s, including listed as "(d) Haardekraaltjie" of the Department of Lands.

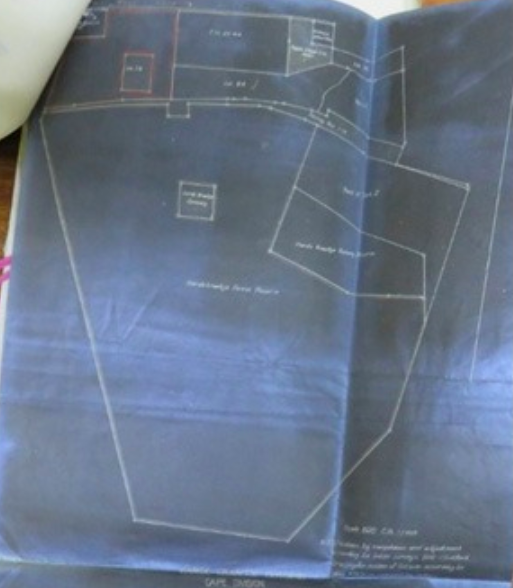

The Surveyor-General gave notice to the Cape Town Provincial Secretary in September 1938 of the Hardekraaltjie Outspan, as unregistered crown land originally known as an Outspan declared in 1874, diagram no. 806/1874 (see image below). However, portions of the land have already been used for other purposes including the cemetery already declared during 1909.

Cape Archives diagram 806/1874

The cemetery's establishment, development and closure

The Office of the Civil Commissioner Cape gave notice to the Cape Divisional Council during January 1910 regarding the availability of the title deed for issuance to the trustees for the management of Harde Kraaltje Cemetery.

In terms of Act 3 of 1883, the Deed authorizes the establishment and management of a public cemetery. The deed granted two morgen of land to the trustees to manage the Harde Kraaltje Cemetery near Bellville. The land was designated as a public cemetery from 4 January 1910. The diagram below shows the direction of the road from the Outspan on the "Hardepad" main road. A letter dated 25 May 1945 refers to the access road which by prescriptive rights has become a public servitude. It was from the Cape Town-Bellville Highway across the Outspan, across the railway line through the old forestry overpass near the gatekeeper's cottage at the railway across the Elsiesriver in a southerly direction to the cemetery.

Access from the Hardepad

The 1941 Hardekraaltjie site still includes the cemetery and a smaller footprint of the Hardekraaltjie reserve.

The burial grounds were granted for the use of the poorer coloured classes initially within the boundaries of the Tigerberg and Kuilsriver field cornetcy. Tygervalley was later allowed to use the cemetery for a period of five years from 1928. In a meeting with the Divisional Council in 1943, a trustee, Mr. Swan, mentioned that people from as far away as Matroosfontein were buried at the cemetery. The trustees in December 1941 were JA Duminy, BW Duminy and JR Smuts of Bellville. AH Swan was appointed trustee with the resignation of JA Duminy and SG Muller in November 1942. The trustees approached the Divisional Council in April 1943 to assist with the maintenance of the cemetery due to the sloppiness and poor maintenance of the grounds. They also sought help with the access road over the Elsiesriver, which was difficult to navigate during the rainy season, and asked for a causeway or bridge across the railway gate. An additional recommendation was submitted to council for the cemetery management to be taken over by the Cape Peninsula Cemetery Council.

After an inspection in April 1944, the trustees of the Cape Peninsula Cemeteries recommended that the Council build a road from the main road and a bridge over the river between the railway line and cemetery before the request could be considered. The Council requested the engineer to conduct feasibility studies for access from Stonehill, Florida and Tiervlei, as most of the funerals would be from these areas. After deliberations, the request was denied due to the cost and the small scope of the cemetery. The proposed alternative access roads were also not a feasible solution. In addition, the South African Railways (SAS) was not amenable for access over their new property.

In July 1944, the Divisional Council engineer reported that a proposal had been submitted recommending the La Belle Alliance Outspan as a cemetery for Bellville, Stikland and Bellville South because it was not feasible to build an access road at Hardekraaltjie. The Divisional Council adopted the proposal in September 1944 to establish a cemetery at the La Belle Outspan Stikland and closing the Hardekraaltjie Cemetery. The Council submitted the request for the closure of the cemetery and the establishment of a cemetery at the La Belle Outspan during October 1944 to the Provincial Administration. The Provincial Administration informed the Council that the Bellville Magistrate offered no objection to the proposed closure during March 1945, provided it was accessible for the families of the deceased to visit the graves. Enquiries have been made as to what provision is made for this request. The SAS confirmed that access over railway land could not be allowed and made an alternative proposal along the new proposed sectional council road or a section along the railway land.

The access from 1910 would be difficult to retain due to the construction of the railway yard. In December 1945 an agreement was reached between the Divisional Council and the SAS. The SAS agreed to allow access to the cemetery via the current access across railway land as already described. Once the railway yard construction began, the old access would be closed and the SAS would provide foot access from the highway west across the main line across the Elsiesriver to the cemetery. The SAS commitment included access across the main line with the erection of a revolving gate in the fence and an access road to the cemetery.

In March 1946, the Provincial Administration issued the order for the closure of Hardekraaltje cemetery under Ordinance 13 of 1917. The trustees of the Cape Peninsula Cemeteries inquired from the Divisional Council in September 1947 regarding the status of the Haardekraaltje cemetery since the opening of the Stikland cemetery. The Council advised in October 1947 that the cemetery was closed for burial purposes only and referred to the Cemeteries Act 5 of 1883 which stipulates the ownership of the land rests with the trustees of the cemetery. There is no duty on the Council to exhume the deceased or for the removal of the remains. The trustees of the cemetery requested the Bellville Magistrate to be relieved of their duties in October 1947, as the cemetery was already closed in June 1946.

The chief health clerk of the Divisional Council recorded the survey of the health inspector, JE Retief at Haardekraaltje, in October 1947. The cemetery is 2 morgen in size. Mr Swan, a trustee, mentioned there had been 539 funerals since 1942. Sadly, there is no record of earlier funerals. Mr Retief observed the cemetery was fenced with barbed wire and graves were scattered across the entire extent of the area, in a neglected state. He estimated that 25% of the western side was overgrown with forest. He counted 701 graves marked by piles of sand, bricks, and wooden crosses etc. It was not possible to accurately estimate the total number of graves, for the flattening of mounds and the activities of moles removed the traces of graves. He counted two graves with marble slabs and eight more graves with wooden crosses with names still visible.

The state of neglect of the cemetery was clear with no control or maintenance plan. During September 1948, the Provincial Administration informed the Divisional Council of the trustees' request to terminate the administration of the cemetery in terms of the Cemeteries Act. They enquired if the Council would be able to take over the cemetery. In December 1948, the Council requested the engineer to submit an estimate for enclosing the cemetery. The Council notified the Provincial Administration in January 1949 of its decision to take over and enclose the cemetery. The SAS informed the Divisional Council in January 1951 that access was no longer possible to the cemetery after the construction of the railway yard. They proposed an alternative access through the new tunnel/subway at Bellville Station, which was adopted in January 1951. The SAS advised in February 1951 that the old access would remain until Bellville station became operational in 1953.

The Parow Municipality requested the Department of Local Government in March 1971 to transfer the cemetery to the municipality. In the same month, Stellenbosch University requested the Hardekraaltjie cemetery property in exchange for the land the university had to relinquish for the Parkdene Main Road System at Tiervlei. The Provincial Department of Administration informed the municipality in April 1971 to follow Ordinance 19 of 1951 in relation to the request in addition to the exhumation and reburial of the deceased.

In August 1971, the municipality requested for the transfer of the cemetery and permission for the remains of the deceased to be relocated. The Director of Local Government was informed, no objections were received during the advertising period. In August 1971, the Department of Health gave permission for the exhumation of the deceased at the cemetery and for the reburials. The Provincial Administration advised the municipality in August 1971 of the conditions for exhumation and transfer of the deceased including the closure of the cemetery. In September 1972, the municipality gave notice to the Provincial Department of Local Government regarding the reburials of the "unknown persons" at the Stikland cemetery which has been moved from Hardekraaltjie cemetery.

The Parow municipality requested authorization for transferring the property to Stellenbosch University for a nominal fee of 10 cents (10c) for the establishment of sporting facilities. The municipality also advised that no objections had been received during the advertising period objecting against the transfer of the cemetery. In October 1972, the Provincial Administration granted permission for the transfer of the Hardekraaltjie cemetery for 10 cents. The above-mentioned piece on the public participation process will be contextualized in a later section to illustrate the injustice done, as it will be discussed to illustrate the significance and importance of the cemetery as a heritage site. Kamete (2007) states development in any environment is influenced by elements such as the political environment and socio-economic conditions of the era. Successive reports commissioned by Stellenbosch University indicate current graves raise the question whether all bodies were indeed exhumed by the Parow Municipality? The reports are discussed in the section on the current landowners.

The Regulatory and Legislative Environment

Property title deed restrictions

The title deed provides the following additional information: 16840/74 conditions for erf/plot 15349, Parow Hardekraaltje cemetery states, the municipality sold the property for ten cents (10c) on 4 October 1972, "subject to such conditions as referred to in the deed dated 4 January 1910", to Stellenbosch University.

The Deed in terms of Act 3 of 1883 authorizes the establishment of a public cemetery and the management of Hardekraaltjie cemetery. The land must be used as a public cemetery from 4 January 1910. The restrictive condition at the time could only be removed or amended by the Removal of Restrictions Act 84 of 1967. The restrictive conditions were not removed or amended when the property was transferred to Stellenbosch University, as it indicates "... is subject to such conditions as referred to in the deed dated 4 January 1910".

Heritage legislation

Democratic legislation regulates the relationship between the state, state institutions and the public with regard to heritage resources. The challenge that needs to be considered, is whether the current legislation adequately addresses the consequences and damage caused by the colonial and apartheid project in disturbing the social makeup of society and the racial classification. Does it also take into account the consequences of the forced relocation of communities and the skewed socioeconomic development patterns based on race?

The National Heritage Resources Act of 1999 informs us that the "national estate" is the heritage resources of the country which are of cultural importance or special value to present society and future generations. The focus for this section is 3(2)(g)-"graves and cemeteries" listed in Part 2 for general protection. Section 36 describes the care with which cemeteries must be dealt with. Section S36(3)(a): No person may, without a permit, destroy, damage, modify, excavate or remove the grave of a victim of conflict or any burial ground or part thereof containing such graves. The legislation further requires in section 36(6) (b) proof of direct ancestry from the representative community to claim authority over the object of heritage. The requirement of proof of descent is problematic. Referring to Hardekraaltje, the cemetery was in part exhumed, pruned and demolished by government institutions. And in the exhumation process, the dead were reclassified by the state as "unknown persons". It becomes difficult to prove "direct descent”, under these circumstances.

Rugg (2000) refers to Meyer (1997) who mentions that cemeteries indicate features of a deceased person's life, date of birth and death. The purpose is to describe and preserve the identity of the deceased. Other physical features of the cemetery include the scope and internal layout, the sanctity and pilgrimage to the site, including the ability to act as an institution for grief and commemoration of a particular individual. The identity of the deceased is entrenched in the landscape as a specific grave, and each grave is registered in the site, giving each family a sense of ownership and control over the portion. These assertions are confirmed in documentation relating to Hardekraaltjie as mentioned earlier, when the Divisional Council's health inspector carefully recorded the cemetery condition during October 1947. It also corresponds with section 2(xiii) of the NHRA Act which defines a grave as a place of sadness and mourning and includes the contents, headstone or other sign of such a place, and any other structure on, or related to, such a place.

However 25 years later, in September 1972, the Parow Municipality gave notice to the Provincial Department of Local Government of the reburial of the "unknown persons" at Stikland cemetery which was moved from Hardekraaltjie cemetery. The cemetery characteristics and the indicators as described as resting place by Rugg (2000) and others no longer exist, as the above signs are no longer visible. Who removed it and where is it? All the more so because the exhumed bodies have been reclassified. The definition as per section 2(xiii) of the NHRA can no longer serve as evidence under these circumstances. This while two reports using ground penetrating radar commissioned by Stellenbosch University (2015 and 2020) to be discussed in another section confirm possible unmarked graves. These unmarked graves suffered a similar fate to the indicative signs — the official address as final resting place was removed and destroyed.

I agree with Jonker's (2005) argument that the current legal and policy requirements have many limitations. In this regard, the colonial management selected the Hardekraaltjie area where the cemetery is located previously in a dense forest away from the developed area. The cemetery was designated for the poorer colored classes. The National Party government of 1948 legalized and implemented the apartheid system of separate development on the basis of race and ethnicity from 1948 to the early 1990s. The cemetery was closed in 1949, and transferred from the Divisional Council to the Parow Municipality, which sold it to Stellenbosch University. changes took place during this turbulent period in the history of the country. During the colonial period, the coloured community using the cemetery was already a disadvantaged group, and during the apartheid project they were further marginalized and oppressed, ultimately subjected to forced removals.

The apartheid legislation was partially abolished with the Abolition of Race-Based Law Act, 1991. The consequences still hang like an uneasy dark cloud over the South African landscape. The Hardekraaltjie cemetery served the communities of the Northern Suburbs from 1910 on and during the time of the Group Areas Act of 1950, which was abolished in June 1991. Apartheid was a system of legalized racial and ethnic segregation between 1948 and 1991 which was enforced by the South African government. Adler (1995:9) reminds us that the Population Registration Act 1950 led to the identification of individuals within their designated racial groups. The law clearly defined every race. Another proclamation of 1959, as amended in 1961, further divided the coloured people into 'Cape Malay', 'Griqua', Chinese and 'other Coloureds'.

Mesthrie (1994) describes how the Northern Suburbs were affected during the first phase of the Group Areas Act in the 1950’s. Initially, the Cape Town Council was reluctant to implement it. However, the Parow, Goodwood and Bellville city councils have indicated from inception that areas north of the railway line will be declared white group areas within their jurisdiction. These were the first areas to apply the Group Areas Legislation in the Cape. A media article reported in 1955 how “Blankes” (Whites) at Parow became the first municipality in the Western Cape to respond to the implementation of the Group Areas Act.

The non-white community was unceremoniously removed from their birthplace and home, damaging or destroying the social structure of the family unit of the communities. The Immorality Act was introduced in 1927 and was replaced by the Sexual Offences Act in 1957. In 1949, the Prohibition of Mixed Marriages Act was introduced. It was repealed by the Immorality and Prohibition of Mixed Marriages Amendment Act of 1985. This legislation criminalized relations between whites and any non-whites. Separate education ended with the introduction of the South African Schools Act in 1996, nonetheless decades of substandard education left the non-white community behind in educational achievement. The Bantu Education Act of 1953 was replaced by the 1979 Education and Training Act. The purpose of Coloured Education Act of 1963 and the Indian Education Act of 1965 was to separate, manage and regulate education between the two races.

The declaration of significance for a site of heritage inscription is derived from the above context of the cemetery in relation to the disadvantaged and oppressed community and their right to human dignity. The community's human rights, access to equal education, right to freedom of movement, creation of home and community including to lay to rest their loved ones was aggressively and violently deprived of them. Regardless of the identity of the deceased buried here or elsewhere after the above legislation has been introduced and changed and even reclassified several times, the following questions arise: How, then, do you apply the current legislative requirement that insists on proof of descent? With the intentional separate educational-policy legacy, how do the disadvantaged communities participate in public participation processes? To be violently expropriated and removed from a home, land and a social environment, how do you protect your heritage, land and culture in a particular environment? Is the post-apartheid state with its current legislation perpetuating and extending the apartheid heritage and legacy of oppression, expropriation and denial of all indigenous communities? Will the state grant heritage status to the cemetery as symbolic recognition of the atrocities of denial and expropriation that have taken place here? Will approval be given by Tygerberg Hospital and Transnet or will the two institutions have an investigation on their part of the site? The state and Stellenbosch University must be held accountable.

The current owner of the land

What is Stellenbosch University's action for redress as an owner who, with their application for the property in 1971, was already aware of the status of the cemetery 50 years ago? What were the university's plans for the cemetery's land during the apartheid period of 23 years from 1971 to 1994, as well as during the 27 years thereafter? What were the steps when they became aware of the bones discovered, and where are they? What is the responsibility to the communities who’s has loved ones here in their final resting place? What is the legacy for future generations and how will the injustice be commemorated? Why did the community have to inform the university of the cemetery?

Ou Hoofgebou, Former Main Administration Building at Stellenbosch University (Wikipedia)

The university has three reports (2014, 2015 and 2020) confirming possible locations of unmarked graves at the site. This was done after the university was notified by the community of the cemetery. The report by Perception Planning (2017) confirms that the cemetery is located within the property of the SU Tygerberg Campus. Two reports using ground-penetrating radar in 2014 and 2015 indicate possible locations of unmarked graves at the site. The report also refers to oral history that points to the discovery of human remains with the construction of the sports field. The Sillito Report (2020) on the Tygerberg Campus Land Penetrating Radar investigation confirms numbered marks likely to indicate places of unmarked graves. The initial area to be scanned, 19 337 m2, was reduced to 15 076 m2 because the university could not get approval for access to part of the original area. The remaining 4 261 m2 lies within the Tygerberg Hospital and Transnet sites.

The Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences (FMHS) is aware of the cemetery on the property and established a Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences Visual Redress Task Team (FMHS VRTT) during 2019. The university established a task team in 2021, which included community members, with the aim of creating a remembrance project. This is a developing chapter on the side of the university.

Photo from the University's consultation process (Stellenbosch University)

Conclusion

The Hardekraaltjie Cemetery story is incomplete and questions have yet to be answered, but the meaning, heritage and potential for redress of the history are indisputable and non-negotiable. The legislative environment has limitations as already described. This includes the public participation processes that were followed at the time as well as current legislation and policies as illustrated. The meaning of Hardekraaltje cemetery is entangled at this intersection of expropriation, urbanization, transformation and heritage. The burial ground provides an opportunity to commemorate, remember and preserve. It is appropriately still on its original geographic space as described in the Burra Charter and the title deed has not been changed. Ground investigative technology has confirmed the presence of possible graves; ancestry is even proven; confirmed by the archive; legislative requirements all ticked. However, is it enough, given our turbulent past and the context of the cemetery?

All cemeteries are significant, as they symbolize different meanings and values for different communities. "What is the nature of our responsibility to the dead?" was one of the questions posed by Pierre de Vos at the University of Cape Town's (UCT) dialogue series in honour of the Rustenburg cemetery discovered on a portion of the University of Cape Town campus (News UCT 2013). With this question, a voice was given to the voiceless and oppressed. On the Northern Suburbs of Tiervlei and Bellville, the Hardekraaltjie Cemetery as a final resting place has already been disturbed and a developing story.

For Stellenbosch University as an institution of higher education, there is an opportunity to recognize the sacred space of memories and create an appropriate site for the community to commemorate. This paper urges the university to acknowledge the injustice done and account for the bones that have been removed. I am strongly arguing in favor of the inclusion of the tangible and the intangible history as a shared history of this part of the university's history in the area. Generations of a voiceless, marginalized community in the Northern Suburbs of Tiervlei and Bellville will thus be recognized as a part of the traumatized people of the area. The successful heritage nomination process will give a voice to the previous voiceless community and restore our human dignity.

Chefferino Fortuin is a community researcher and student at UCT (MPhil Conservation Studies). This article was first published in Afrikaans medium Litnet, 29 October 2021. Click here to read the original including references.

Chefferino Fortuin

Bibliography

- Hayden, D. 1995. The power of place: Urban landscapes as public history. Cambridge. The MIT Press.

- Younger, J. 2005. Excavating the legal subject: The unnamed dead of Prestwich Place, Cape Town. Griffith Law Review, 14:2.

- Mesthrie, U.S.A. 1994. "No place in the world to go" – Control by permit: the first phase of the Group Areas Act in Cape Town in the 1950s. Studies in the History of Cape Town, 7, 187.

- News UCT article, December 30, 2013. https://www.news.uct.ac.za/article/-2013-12-30-rustenburg-memorial-dialogue-series-honours-slaves (Accessed August 2021).

- Perception planning. 2017. Proposed redevelopment of the Stellenbosch University (SU) Tygerberg Campus, On erf 24602, 18228 & 15394 (Parow), City of Cape Town.

- Roders, AP and F Bandarin. 2019. Reshaping urban conservation: The historic urban landscape approach in action. Singapore: Springer.

- Rugg, J. 2000. Defining the place of burial: What makes a cemetery a cemetery? Mortality, 5(3):259–75.

- Sillito, 2020. Stellenbosch University – Tygerberg Campus Ground Penetrating Radar Survey Report, Hardekraaltjie Cemetery Site.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.