Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

We found the following article by B.I. Spaanderman in the 1991 edition of the old Johannesburg Historical Foundation's journal Between the Chains. It looks at a number of South African mills with a particular focus on Millbank, the closest to Johannesburg.

For a mere fifty cents you can ask the watchman at Bradshaw’s Mill in Bathurst to set its wheel in motion. It costs a few cents more in Graaff-Reinet. The beautifully restored Josephine Mill in Rondebosch is a delight, and an informative booklet has been produced by the Historical Society of Cape Town describing its history and restoration.

The water-mills of South Africa are mainly located in the Cape Province by virtue of the settler population. These were built from the late 1600s to the late 1800s. Mills in Natal, the Orange Free State and the Transvaal were built from the middle to the late 1800s. The most definitive study to date is Water-mills, windmills and horse-mills of South Africa by James Walton, published in 1974. Owing largely to his interest, a number of the mills have been restored, such as the Josephine Mill, but more sadly, many have been left to decay, or have been destroyed by fire and other natural disasters.

Bradshaw’s Mill was built by the 1820-settler Samuel Bradshaw and his brother. He was assisted by the young Jeremiah Goldswain, who worked for “Measerss Bradshaws and Wiggall for servel months, at this time cash was so scarce that it was almost imposable for andy one to be paide for your work in money…” (Volume I, p 41). Yet building the mills was essential, despite the financial paucity of the colony, because grain had to be ground once the settlers had established their crops.

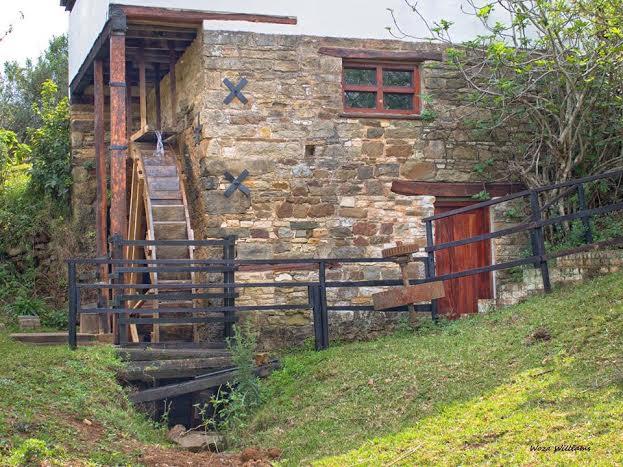

Bradshaw's Mill (via Bev Young)

Josephine Mill was built in 1844 by the industrious farmer and brewer Letterstedt, who named it after the Swedish crown princess. In 1888 it was leased to another Swede, Anders Ohlsson - the name of a well advertised beer. The mill had changed hands several times until it was bought by the Historical Society of Cape Town in 1975, which then set about restoring it.

By and large, the restoration of mill houses depends more on public grants from interested people than on the small donations received by a curious public. Alternatively, they can be owned and restored privately. The mill at Caversham, near Howick, built by the Hodson family in the late 1800s, was constructed from corrugated iron. In recent years it was owned by potter David Walters and opened to the public on the Midlands Meander. The workings were made of cast iron and the cogs of yellowwood. Sadly, the entire building was washed away in 1987, when the overshot cast-iron wheel cracked, and only a few pieces of inner workings remain. At present, Caversham Mill is owned by Mr and Mrs Buckle. John Buckle is South Africa’s only private restorer of paintings and old maps. His studio overlooks the remains of the mill, fed by the Lions River. The possibility of restoring this mill appears to be remote because of the severity of the damage caused by the floods.

The remains of Caversham Mill, near Howick, showing the transition in construction from wood to cast iron on the overshot wheel

Over 1800 mills have been built in South Africa. The one nearest to Johannesburg, Millbank, is situated near Kromdraai, just to the west of the Swartkop hills. One of the few mill houses in the Transvaal, it is unique in the province in that it appears to have been the only mill to use a horizontal wheel. One would have to travel to Potchefstrrom to locate our city’s second nearest restored mill. There are several run-down mills in the Magaliesberg.

Located on the Blaaubank river, which flows into the Crocodile five kilometres further, Millbank has a perennial water supply. The River is sourced from the subterranean lake that can be viewed in the Sterkfontein Caves. Millbank was bought in 1983 by Cor and Wil Spaanderman from a company that had allowed it to fall into disrepair. Its previous owner, a Mr Botha, had turned the property into a trout farm in the sixties.

About 150 metres to the north-west stands the original c. 1880 four-roomed farmhouse built from rock and dagga, square in design, with its low interior doorways, typical of the 19th century Transvaal farmhouses. The doorways of the four rooms lead into a diamond-shaped vestibule in the centre of the house. Whereas the stone used to build the farmhouse was collected from the immediate vicinity, that used in the mill is thought to have been brought from the mines nearby.

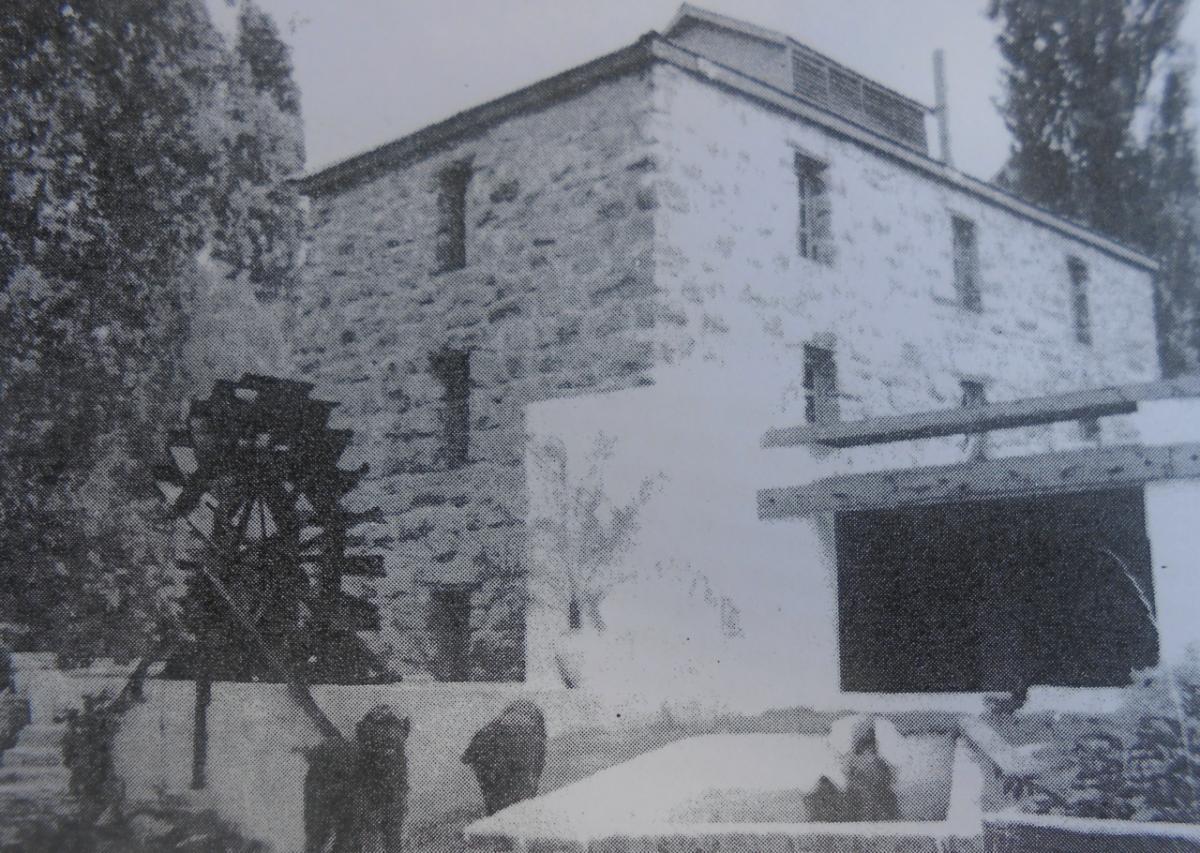

The original farmhouse at Millbank built from rock and dagga c. 1880

There is not much data available on the mill. The Africana museum has one photograph of the building from which it can be established that it was built in two stages. First, the ground floor was built between 1880 and 1890, and the upper floor was added before the turn of the century. Its present roof - corrugated iron with wooden louvres - was probably added at the same time. The mill, according to Mrs Pyper who grew up there, was still operational in the twenties.

The stonemasonry reflects the care and the quality of the engineering skills of its builders. The stone blocks were hewn symmetrically, and the mill was built in much the same style as the Makhaleng Mill in Zastron in the Orange Free State. The building also reflects the ingenuity of its builders. The window and door lintels were not made of wood but from pieces of cocopan track probably plundered near Krugersdorp, originally known as Paardekraal. Excavations in the shaft of the wheel revealed other items from which the history of the mill house could be pieced together. The gears, (specifically the walkovers) each with a mass of 70 kilograms or more, were hauled out of the pit. They are cast iron and are similar in design and shape to the gears used in the mill at Mamre (near Malmesbury) built in 1844. However, where the mills of the Cape used wooden shafts, the one at Millbank is made entirely of cast iron. This may be because the mill is of a later vintage and quite possibly because the original builders were financially better able to cope with the cost of a completely iron construction than earlier millers who slowly converted from wood and iron. The remains of the mill at Caversham show the transition from wood to cast iron as the two materials are used with obvious compatibility.

The wheel at Millbank, as has been mentioned above, was a horizontal one. No hole in the building leads to an outside wheel. Instead, the water, dammed up in an impressive dam made with stone buttresses, leads directly into the shaft where the wheel (and a turbine) is housed. The extra height afforded to the water by damming it increases water pressure needed to run a horizontal wheel as powerfully as a vertical wheel outside wheel. Therefore, one is led to assume that the mill must have been of less common horizontal variety, possibly built by Scotsmen who were familiar with this style of construction.

The mill house was restored as closely as possible to its former state. The basement was concreted and the two floors virtually completely replaced except for the cross-beams, which are still the original wood. The open holes were given wooden windows, and wood doors were fitted in the basement and ground floor. The cast-iron hoist on the upper floor bears testimony to the mill’s use as a house for grinding and storing corn. Other features now adorn the mill house. It boasts a bar and a fireplace - neither of which are attached to any of the permanent structures of the building. In another context, Walton refers to the “feeling of peaceful… industry which has almost disappeared from twentieth century life”. The point remains: a mill, even if no longer industriously employed in grinding corn, still retains a feeling of prosperity and domestic industry. Mills, once associated with the richness of the harvest, feel anthropomorphic particularly if cared for by their owners. The final embellishment in 1989 to the mill house at Millbank is a British undershot wheel, so that the mill’s original function is no longer held secret from the visitor.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.