Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

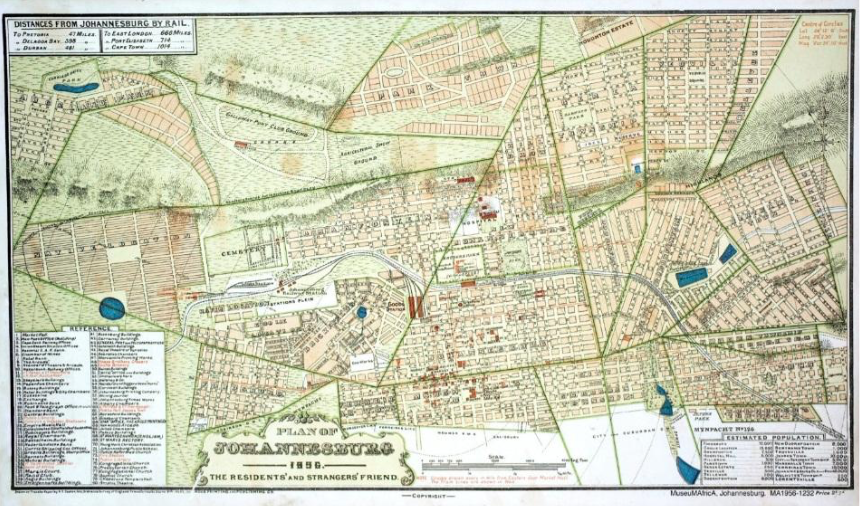

In 1896 Johannesburg had reached its tenth birthday. The astounding growth of the town in its first decade meant that the authorities (at that stage It was the Johannesburg Gezondheids Comite or the Sanitary Board / Committee) wanted to know about the population of the town, its origins, location, composition, religions, local industries and occupations. The Sanitary Committee decided that a census of Johannesburg and its suburbs, within a three mile radius from the Market Square should be taken to capture accurate statistics to plan ahead for the needs of the new town. They wished to address issues of sewerage, drainage, property assessment rates in “a progressive town like Johannesburg”.

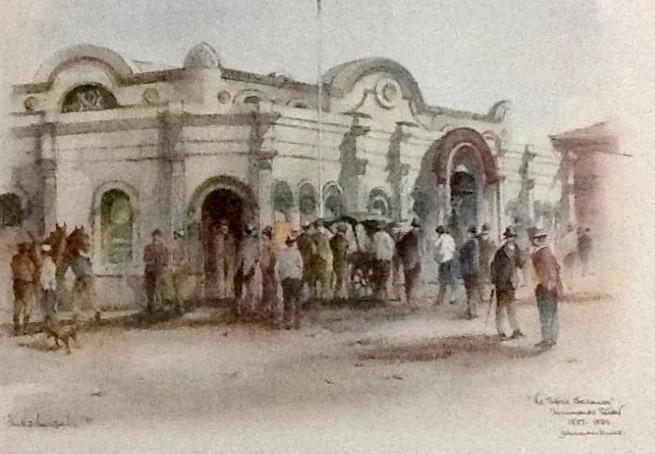

Market Square circa 1892 (Davies Brothers)

Census Essentials

The Census was conducted on 15th July 1896 under AH Bleksley, the Director of Census. The report was published some two months later on 15th September. It is a substantial document of many fold out pages of tables. The printing was undertaken by the Standard and Diggers’ News in Johannesburg. It is an extraordinary report because it is sophisticated, meticulous and detailed in the tabulations. The report opens up a window on early Johannesburg from an entirely different angle. The Sanitary Committee had to deal with a problem of jurisdiction and coverage; Johannesburg comprised the area administered by the Sanitary Committee and their authority extended over six wards and Brickfields; however, added to this were the settlements that fell outside the jurisdiction of the Sanitary Committee that extended to the 3 mile radius from the Market Square, covering suburban townships, east and west mine, Doornfontein etc. The enumerators attempted to work within census districts. Unfortunately there is no accompanying map.

Brickfields (Museum Africa)

The census report starts with a quick summary by Bleksley and then moves through several sections such as population, races and birthplaces, religion, ages, conjugal conditions (whether married, single, widowed or divorced), education, occupation, languages franchise (whether a man was a burgher of the Zuid Afrikaans Republic) or a naturalized subject or without a vote and hence an “uitlander”, dwellings, buildings and livestock and industries. It is a wonderful item of raw history of Johannesburg in its early days. The timing of this census was significant because it came after the Jameson Raid (end Dec 1895 and into early 1896) and preceding the Anglo Boer War of 1899.

The 1896 census involved an enumeration on a house-to-house basis and involved 97 enumerators, in addition to the director and his office staff, supervisors, and interpreters. The total staff engaged in the exercise was 135.

The 1890 Census

The report also contains the summary taken in January 1890. Johannesburg at that date was split into 6 wards and the summary provides the quick statistics on the population, the number of buildings, the number of shops and stores, and the number of hotels and bars. In 1890 the population of the town was recorded as 26 303, but there was no significant break down into races or sexes.

Grand National Hotel circa 1892 (Davies Brothers)

Johannesburg in 1887

Looking back on Johannesburg History, Bleksley’s report includes perhaps the first bit of “history” of Johannesburg, with an account of what had changed in the town from the date of the official founding of the city on 20th September 1886 to mid-1890. The principal source of the information is the Diggers News of 7th April 1887.

The town of Johannesburg in 1887 extended over 1.5 miles but with the “built–up area” covering only 3/4s of a mile; the township was high and sloping, so well drained; no single church has been erected; the population of Johannesburg including Natal camp was about 3 000. The town was built partly on Randjeslaagte (that triangular expanse referred to as a “small Government farm” and portions of the farms of Braamfontein and Turfontein (no mention was made of Doornfontein or Langlaagte in these early notes). By 1887 the streets had been regularly laid out and several squares were dotted about the townships. Trees are beginning to be considered to be important – “when people have time to plant trees and shrubs, will add much to the appearance of the town“. A telegraph office was opened on 26 April 1887; the first stock exchange was opened in November 1887 and the first church, St Mary’s (the Anglican church in Jeppestown) held their opening service on 13th November 1887. By 1887 the Sanitary Committee had ruled that no more reed houses or fences should be built.

Mosaic showing Randjeslaagte (The Heritage Portal)

First Stock Exchange (Philip Bawcombe)

Geographical spread of Johannesburg in 1890

One gains an excellent sense of the expanse of Johannesburg by 1890, by delving into the coverage of the 6 wards. There were 3 large wards - 2, 3 and 4; wards 1, 5 and 6 were much smaller. There was a fluidity between the mines, the townships which lay outside of Johannesburg (which was laid out on Randjeslaagte), some early suburbs, what was called the Coolie location and the surviving portions of farm land. By 1890 the townships were Booysens, Height’s, Marshall’s, Ferreira’s, Prospect, and Jeppe’s. Mining activities are grouped under the heading Mining Companies and outskirts and Native Locations. In addition Fordsburg, United Langlaagte estate, Braamfontein, Auckland Park, Veldtschoendorp are mentioned in the tabular breakdown of the 6 Wards.

A summary of the 1896 Census

Population in 1896: 102 078 of which roughly 60 % fell within the jurisdiction of the Sanitary Board and the remainder living beyond but within 3 miles of Market Square. The racial breakdown was 50 907 whites or Europeans, 952 Malays, 4 807 Asiatics, 42 533 “Native Kafir Tribes” (sic) and 28 907 were mixed and other races. One assumes that the incipient Chinese population falls within the category Malay and the Indian population falls in the category Asiatics. Black, indigenous people fall into the 'Native Kafir Tribes'. Elsewhere in the report the term “natives” is used, pointing to the very early sharp categorization of people according to race and hence their separation into compounds (mine labourers working on a migrant labour basis), locations (Indian people and coloured people) and suburbs (largely white residential but with servants who could have been black).

Johannesburg in 1896 was a male dominated place with men of all races forming 80% of the population; most of the women in the town were white or European.

It is interesting that by 1896 there were 23 suburbs with Doornfontein being the largest.

There were 24 mines and the mine with the highest population is Wolhuter Mine and the smallest is United Langlaagte.

The “Native“ population in 1896 amounted to 42 533; most hail from Zululand and Natal, but also arrive from Basutoland (today’s Lesotho) the Cape Province, “other British protectorates”. It is noteworthy that the second largest group come from the Portuguese Territory or Moçambique. Almost all the black workers were mine workers so the black men outnumbered the black women in the town by over 24 to 1.

Whilst the black population were born in Africa, the white population were born in roughly equal numbers in Africa and in Europe and just under 1000 came from Australia.

Religion: Johannesburg attracted people of all religious denominations but also with a large number of people entered on the census as pagans or heathens. There were protestants, Catholics, Jews, Muslims, Hindoos, Budhists, Brahmins and Confucians. There were even some atheists in town. We can draw the inference that early Johannesburg needed churches, synagogues, temples, mosques to cater for a diversdity of religious beliefs.

Ages: Johannesburg had a young population as to be expected for a new town, more than 60 per cent were under the age of 30 with the largest age group being the 25 to 30 year olds. Johannesburg attracted men in the prime of their lives. A handful of people were over the age of 80.

Marriage: The statistics on conjugal status yielded no surprises. By the mid 1890s people were getting married. Roughly double the people were single compared to married; sometimes men were married but had left their wives elsewhere in South Africa or at home in England or elsewhere.

Education: These statistics point to a keen desire to address the educational needs of the population. They reveal that illiteracy was evident but only a relatively small number of the European population could neither read nor write. But of over 4 500 children undergoing instruction there was another large group of nearly 7 000 who could not read or write and were not in schools. By this date there were 66 schools in Johannesburg with over 4 600 pupils; of that number 55 schools were for white children, 7 for coloured children and 4 schools where both white and coloured children were admitted indicating that the colour divisions existed but that there were a couple of opportunities for mixing. By this date some schools had their own school buildings, but some schools were run in church buildings in private houses. The big schools were located inside Johannesburg proper. Most teachers were female (of 197 teachers, 131 were female and 66 male). 59 of the 66 schools admitted both boys and girls. The report gives a fairly comprehensive picture of early education.

Occupations: The census data on occupations gives a fascinating coverage of the world of work. Occupations are broken down principally into Professional, Domestic, Commercial Agricultural and Dependents. There were government officials, and inspectors, 612 Police employees, but only 36 men working in sanitary (effective health) work. Already by 1896 there were 87 architects, 19 dentists, 50 photographers, among other professions. The more unusual occupations included a single organ grinder, a wax work proprietor, a single sexton, three merry-go round owners, 14 midwives, 2 masseurs and 6 billiard table keepers. As was to be expected there were several hundred engineers, constituting the largest category of professional employment. There were 143 people making their living from the law but also 87 musicians. Religion kept many busy with 46 ministers of religion, 14 missionaries and 12 nuns. Many were involved in the hospitality trade - boarding house, coffee shop, hotel and eating house keepers, and over 6 000 fell under the domestic service or servants headings. In Transport the largest single occupation group were the cab drivers - 692 of those. Johannesburg had its bakers, barmen, butchers, brewers, cigar makers, fishmongers, distiller’s dairymen. There were 26 mineral water manufacturers and even 10 wine merchants. There were 317 prisoners and 114 prostitutes.

The picture emerges across the occupations for 102 000 people of a sophisticated mining town, strongly male dominated in the work place. It’s a rich varied social fabric - mines, building trades, transport activities, were all there. People had to feed themselves - they ate, drank and were merry. They entertained themselves and many looked for spiritual succor in churches. The occupation section ends with an alphabetical list of all occupations - everything from accountant through the gardeners and machinists to undertakers, vagrants wood turners and workmen.

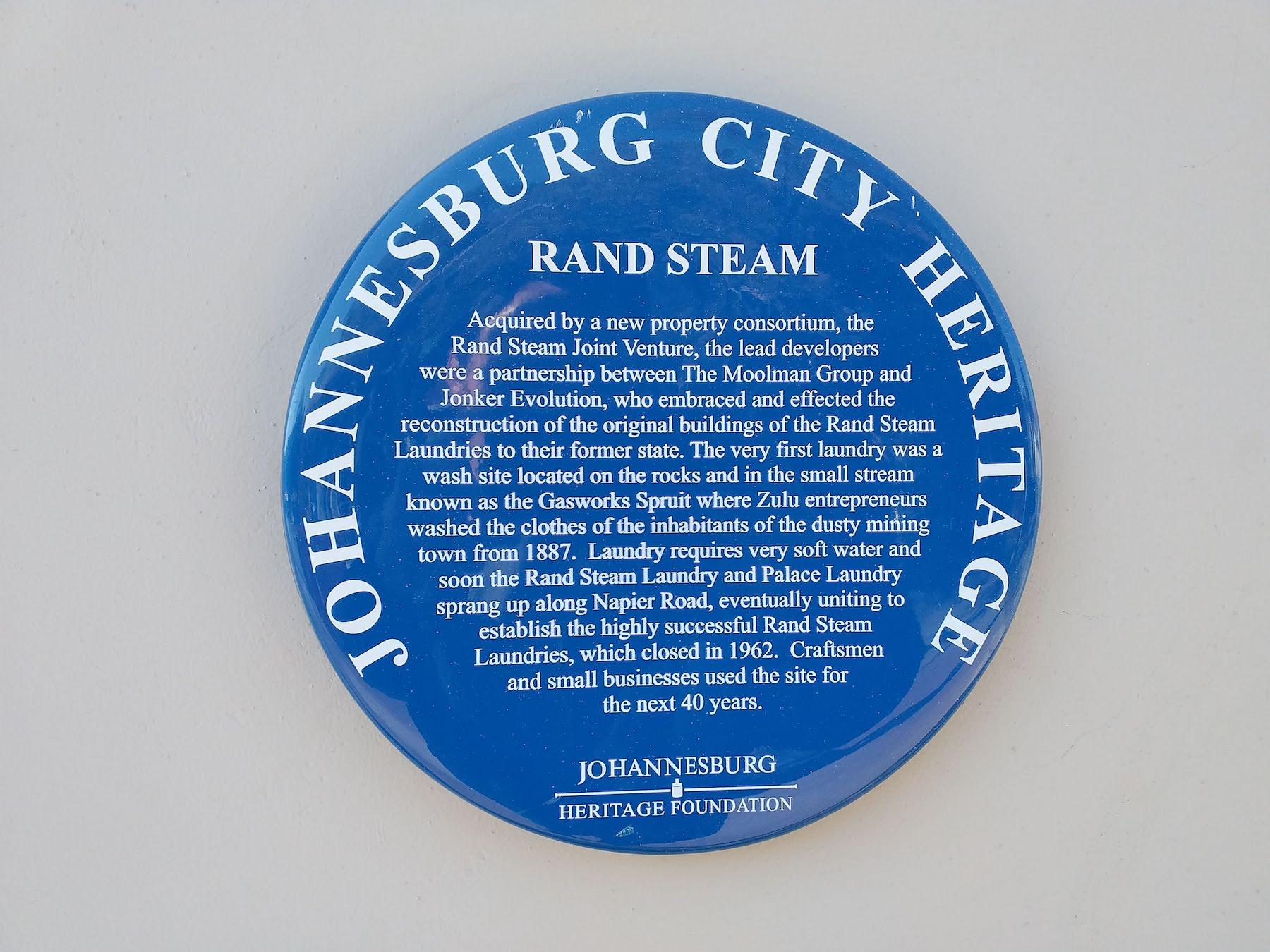

Industries: Part X of the census covers the many types of industries that had sprung up in the first decade. Biscuit making, brewing, brickmaking, carriage works, building materials, coffee manufacture, distilling, engineering works and foundries, flour mills, gas works, harness and saddle making, hide curing, ice making, mineral water manufacturing, bookbinding and printing, stone cutting, timberworks, the tobacco trade, workers in precious metals. One surprising economic activity is the listing of “wash boys” - these were the distinct category of laundry men; there were 543 such wash boys and they were black males who did hand laundry for the hotels and boarding houses. It was a service the bachelors of the town valued. Charles Van Onselen in his book “New Babylon” describes how from 1890 small groups of Zulu-speaking washermen, established themselves on the banks of the Braamfontein Spruit in the vicinity of San Souci to the west of the town. He comments “they formed an association of Ama-Washa and won recognition from the Sanitary Board“. Van Onselen gives a figure of 100 to 200 such washermen, but that number must have grown to the 500 plus by 1896 the date of the census.

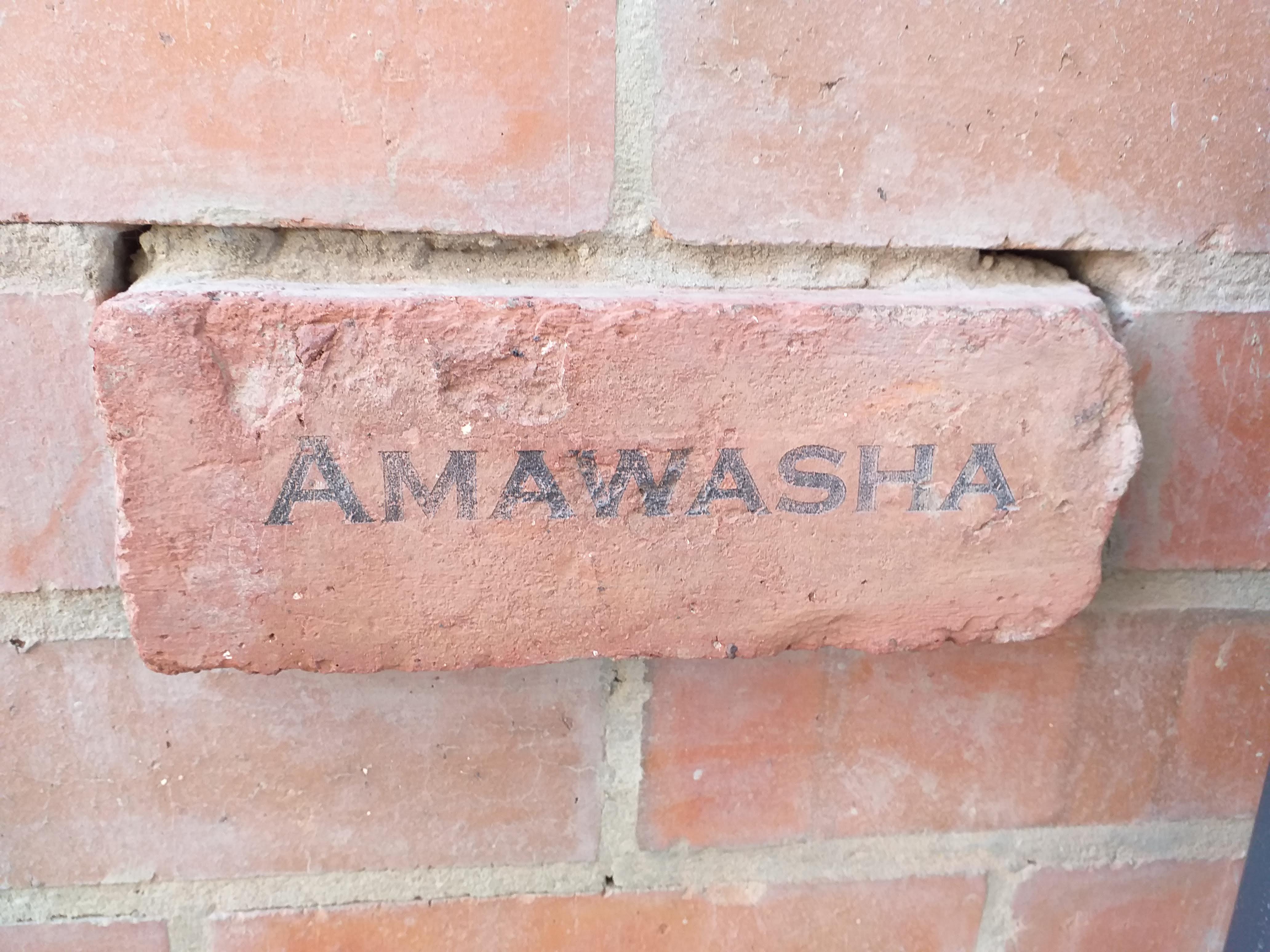

AmaWasha commemorated at Rand Steam, Richmond (The Heritage Portal)

Blue Plaque mentioning the Zulu entrepreneurs (The Heritage Portal)

Amawasha Protest March (New Babylon)

The Franchise: The section on the Franchise is of relevance because in 1896 the vote was only held by white European males over the age of 16 enfranchised in the Zuid Afrikaanse Republiek or ZAR. Women, blacks and people of colour could not vote. This meant that of a total of 25 050 23 500 were not entitled to vote, quite apart from women and black people. The voting population was a minute proportion, about six percent of adult white males could vote. Here was the principal grievance of the Uitlanders or foreigners, but as Barney Barnato said, people did not come to Johannesburg to vote, they were here to make money! The occurrence of the Jameson Raid and its failure was the context for the establishment of the facts about the franchise in a census. This was the period of build up towards the second Anglo Boer war and the question of the franchise was a hot political topic of the day.

Jameson

Dwellings, Buildings and Livestock: The table on dwellings and buildings of Johannesburg is a fascinating though limited source of information on housing and on commercial buildings. There were approximately 14 000 dwelling houses in all of Johannesburg in 1896 and this included inhabited and uninhabited houses and those under construction. Over 9 000 fell within the reach of the Sanitary Committee and the balance lay in the newer suburbs such as Yeoville, Houghton, Bellevue, Doornfontein Ophirton, Booysens, and on the mines close to the town - Yeoville had exactly 22 dwellings, Berea 13, Bellevue 2 and Houghton Estate 1. 1896 was the year when Barney Barnato’s mansion at Barnato Park in Berea was under construction but it was incomplete. The description of the dwellings of the town was very elementary broken down into the categories of brick and stone, wood, iron, lath and plaster and “all others “.

Old postcard of the mansion

The census also extended to the livestock kept in the town – horses, mules and asses, horned cattle, sheep and goats, pigs and dogs. In 1896 horses, mules and asses were essential for pulling carriages, cabs, carts and moving people, produce, building materials throughout the ever expanding town. The census gives a precise tally of 11, 242 horses, mules and asses within that three mile radius of Market Square. Horses in harness pulled the horse-drawn trams. Early post cards and photographs of Market Square show the chaotic mix of people, cattle and animals.

Old photo of Market Square

Conclusion

The 1896 census report is a fascinating and quite extraordinary document. It gives us a statistical window on Johannesburg just ten years after its founding. The old phrase ‘ the devil is in the detail' can be extended to 'the devil is in the raw data'. This report is underutilised and appears to be little known. I have no idea whether the actual household census returns were retained and if so, where these would have been archived. The report and the supporting tables are sophisticated and detailed. The report can be tracked through the World Catalogue online and a hard format copy is available in the National Library of South Africa in Pretoria; and a number of other libraries around the world have copies of the report. The standard approach to census taking is that this should happen every 10 years but this was a time of turmoil. There was a British Empire census taken in 1901 and a Transvaal Colony census in 1904; following Union there was a 1911 census and this then set the pattern for census taking for South Africa every ten years thereafter until 1991. Following the change of government in 1994 the first major census of the new South Africa was in 1996.

Kathy Munro is an Honorary Associate Professor in the School of Architecture and Planning at the University of the Witwatersrand and chair of the Johannesburg Heritage Foundation. She enjoyed a long career as an academic and in management at Wits University. She trained as an economic historian. She is an enthusiastic book person and has built her own somewhat eclectic book collection over 40 years. Her interests cover Africana, Johannesburg history, history, art history, travel, business and banking histories. She researches and writes on historical architecture and heritage matters. She is a member of the Board of the Johannesburg Heritage Foundation and is a docent at the Wits Arts Museum. She is currently working on a couple of projects on Johannesburg architects and is researching South African architects, war cemeteries and memorials. Kathy is a member of the online book community the Library thing and recommends this cataloging website and worldwide network as a book lover's haven.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.