Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

Death, or more specifically images of the dead, remind us of our own mortality. During the mid 1800’s to early 1900’s, photography played a vital role in capturing images of loved ones, not only whilst alive, but also at the time of their death.

Where citizens could not afford a painted portrait of a loved one, photography was a cheaper and quicker alternative, providing the middle class with a photographic image in memory of a loved one who had passed away.

Postmortem photography (meaning after death), also referred to as bereavement or Momento Mori (Remember you are mortal) photography, was an integral part of the mourning and memorializing process during a time when death played a more visible role in the population’s day-to-day life.

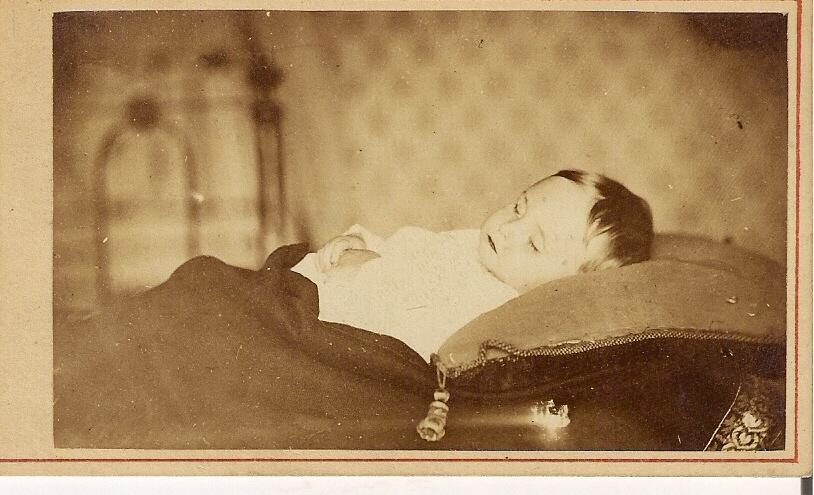

These photographs were especially common for infants and young children as Victorian/Edwardian childhood mortality rates were high.

Postmortem photographs of young children were common

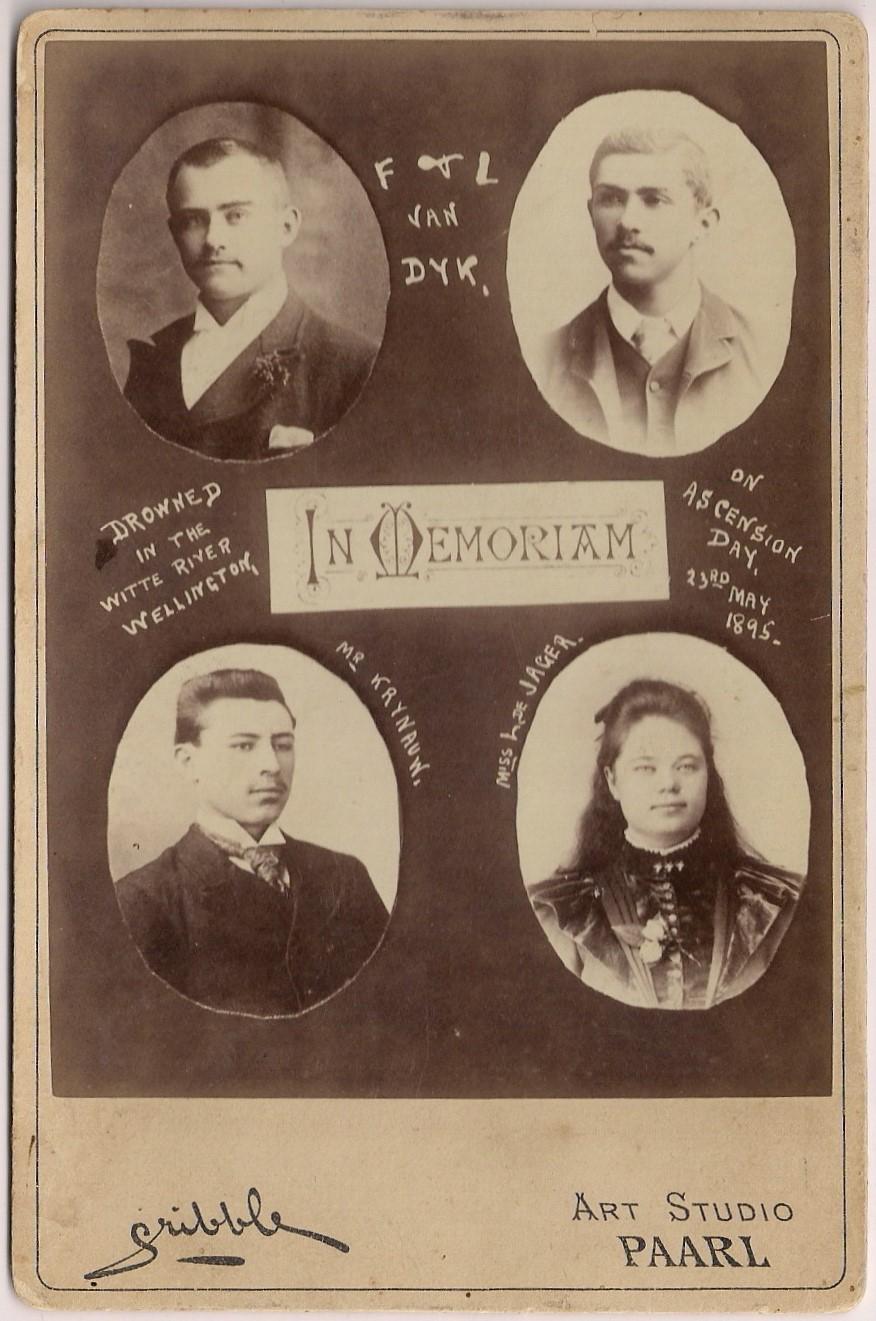

Although the words postmortem and memorial photography are used interchangeably when referring to photos of the dead, postmortem photographs relates to images taken of individuals after they have passed away, whereas memorial photographs are reproductions of photographs taken of the remembered from when they were still alive (see image below of four young people who drowned in the Witte River during 1895 as an example). On occasions, such images were also mounted in jewelry pieces such as broaches and pendants.

Four young people who drowned in the Witte River

Postmortem photography, a practice that peaked in popularity around the end of the 19th century, has faded into history, whilst the use of memorial photographs is still in use today.

However morbid it may sound, some photographers in the late 19th and early 20th centuries specialised in this art. Postmortem photographs were mainly taken where no living image of the deceased existed. Some images produced are of the highest aesthetic and technical quality, whilst other surviving images are of poor technical quality or have faded over time.

Postmortem photographs served less as a reminder of mortality and more as a keepsake to remember the deceased. Multiple paper prints could be made from images on negative glass plates and mailed to relatives. Sadly, the unfortunate stigma attached to this style of photography has resulted in the loss and destruction of many of these images.

The common practice of postmortem photography in the Americas and Western Europe largely ceased during the early 20th century, as the portrayal of such images was increasingly perceived as vulgar, sensationalistic and taboo. This is in marked contrast to the beauty and sensitivity perceived in the older tradition, indicating a cultural shift that may reflect and confirm modern man’s discomfort with death.

Postmortem images of adults clearly show that the individual has passed away, whilst in images of young children, often on the lap of a parent, it is not always that obvious. The children appear merely to be sleeping. Sadly, more often than not, there are no inscriptions on the back of these images to indicate who the deceased person is or to confirm that the child has actually passed away.

In many of these images, the deceased is either depicted as being peacefully asleep, or else arranged to appear more lifelike. Most of these images can be described as serene or even as thought provoking in appreciating the gift of life.

A young child depicted as being peacefully asleep

In Europe and the USA it was not unusual for Victorian photographers to advertise their skills in the area of postmortem photography. In South Africa, the author has not come across any photographer advertising such skill, although some photographers, such as Roe based in Graaff Reinet, Scholtz from Aberdeen and de Villiers in Stellenbosch (amongst potentially various others) are known to have taken photographs of people shortly after their death.

The author therefore suggests that postmortem photographs by South African photographers are not as common and will therefore not be identified or found as often as in Europe or USA. The author’s own extensive South African photographic research collection holds less than 10 such images. Any such images surfacing therefore need to be treasured. A few more such images may exist in South African Museums.

It has been suggested that the largest postmortem photographic collection is housed at The Burns Archive in the USA.

Surviving postmortem images have become highly collectable worldwide. These images have also been used to document and explore the process and experience of death by anthropologists, researchers and scientists. Various photographic books have been published on postmortem photography, treasuring this historical and misunderstood imagery.

References:

Answer.com – Postmortem and memorial photography – Extracted from the internet on 8 March 2011

Hardijzer, C.H. – Photographic research Collection

Malherbe, A. – Researcher on Graaff Reinet photographer William Roe. Email communication dated March 2011.

Wikipedia – Postmortem photography – Extracted from the internet on 8 March 2011

This article is a slightly amended version of an article published in the Africana Society (Pretoria) annual booklet.

Carol is passionate about South African Photographica – anything and everything to do with the history of photography. He not only collects anything relating to photography, but also extensively conducts research in this field. He has published a variety of articles on this topic and assisted a publisher and fellow researchers in the field. Of particular interest to Carol are historical South African photographs. He is conducting research on South African based photographers from before 1910. He is also in the process of cataloguing Boer War stereo images produced by a variety of publishers. Carol has one of the largest private photographic collections in South Africa.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.