Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

In researching this article, it became evident that hardly any photographer active during the Anglo-Zulu War (AZW) period has been written about. In the majority of sources consulted, photographers also generally have not been acknowledged where their work was used – be that as photographers out in the field or studio based photographers. This may be a simple matter of us not being aware of who the photographers were in the majority of instances. AZW photographic activity is therefore still a field with much research opportunities – this almost 140 years after the event.

Although hand-held cameras of the late 1870’s became more widely used in South Africa, they generally would not have ventured into Zululand by then.

Fewer soldiers would also have carried cameras during the AZW compared to the Anglo-Boer war some 20 years later. Photography during the 1870’s was a slow and difficult process appealing mainly to the professional photographer.

It was also impossible to take action photographs of any battle in progress resulting in the images available showing posed groups or views of historical sites taken some months later.

A large portion of images produced during the Anglo-Boer war would have been taken by soldiers and citizens alike, whereas the majority of images originating from the AZW period would have been produced by the more professionally inclined field and studio photographers. The AZW also took place over a much shorter period compared to the Anglo-Boer war, resulting in fewer images being produced compared to the latter.

During the entire campaign, some 8800+ casualties were recorded on both sides. The British force of around 14 000 men, during their first encounter, marched into Zululand to attack the Zulus on 22 January 1879 when they unexpectedly met up with the 30 000 strong Zulu army at Isandlwana. The British lost around 1 300 men in this disastrous engagement.

Photographs taken of the battlefields afterwards show burnt-out waggons and the bleached skeletons of the soldiers before they were buried.

This article focuses mainly on some of the personalities involved in this conflict, photographed shortly before or after the war. All the images form part of the authors photographic research collection.

Original images taken of Zulu leaders or even Zulu warriors during this conflict are exceptionally rare. It may therefore make this article seem biased from a Eurocentric perspective in that the images included are mainly of British leaders or soldiers.

British soldiers generally had themselves photographed before or after the war, whereas the concept of having oneself photographed would have been a foreign concept to the Zulu nation.

It also begs the question, can we as South African’s argue that the AZW forms part of our heritage. The author argues that it forms an integral part of our cultural heritage for the following reasons (amongst other):

- It was a war against a part of our nation – fought on South African soil;

- Parties from both sides lay buried on South African soil;

- Photographs were taken on South African soil;

- Photographers involved in many instances were South African based;

- The battlefields remain a large tourist attraction.

The majority of the images presented in this article are in carte-de-visite format (the smaller photographic format in use between the 1860’s and 1880), in that the larger format Cabinet Card photographs did not come into use in South Africa until around 1880.

Surviving photographs taken in the field are also exceptionally scarce, resulting in all the images included in this article being studio based photographs (with the exception of the Dabulamanzi image – which was taken after the war).

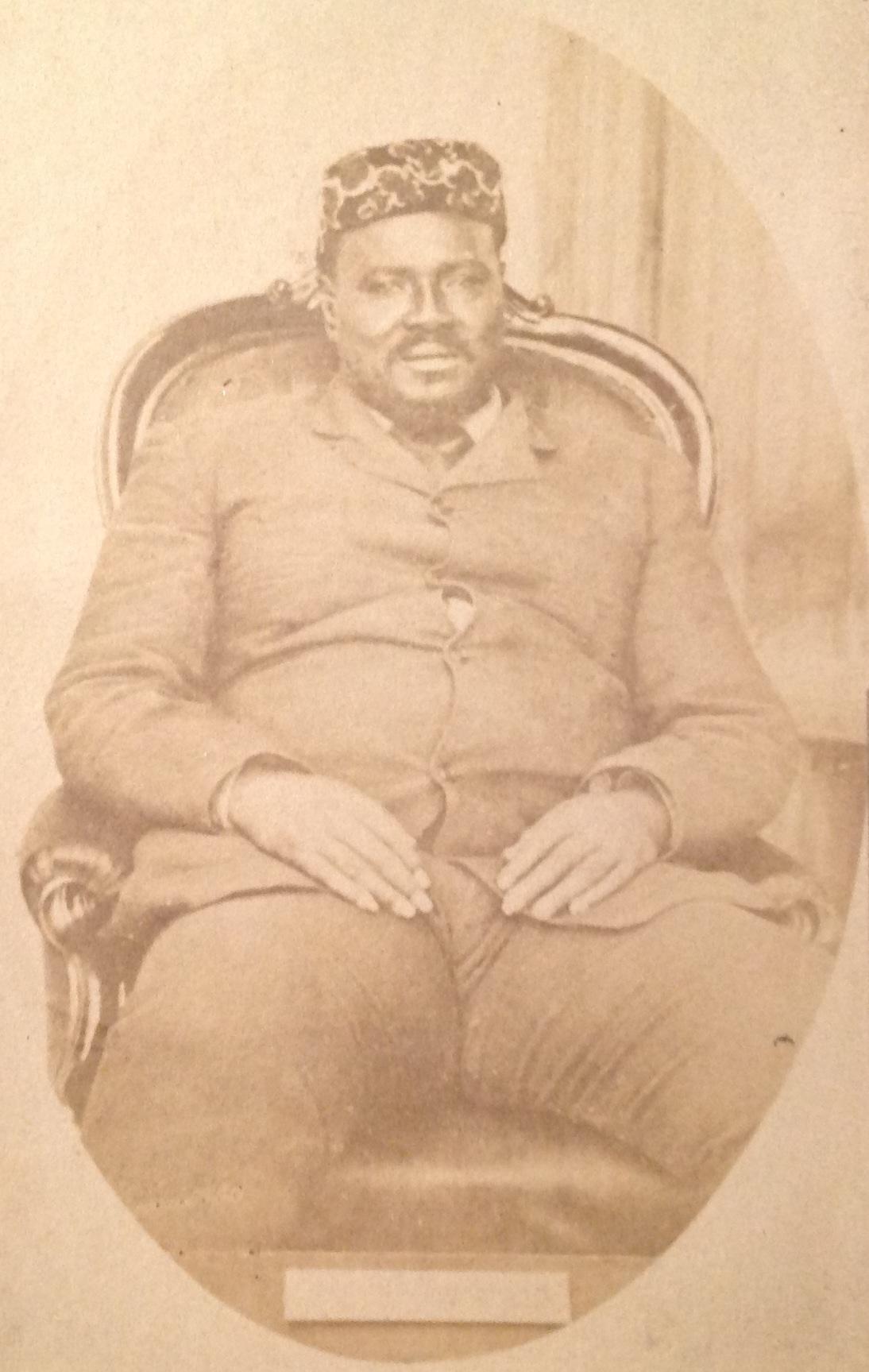

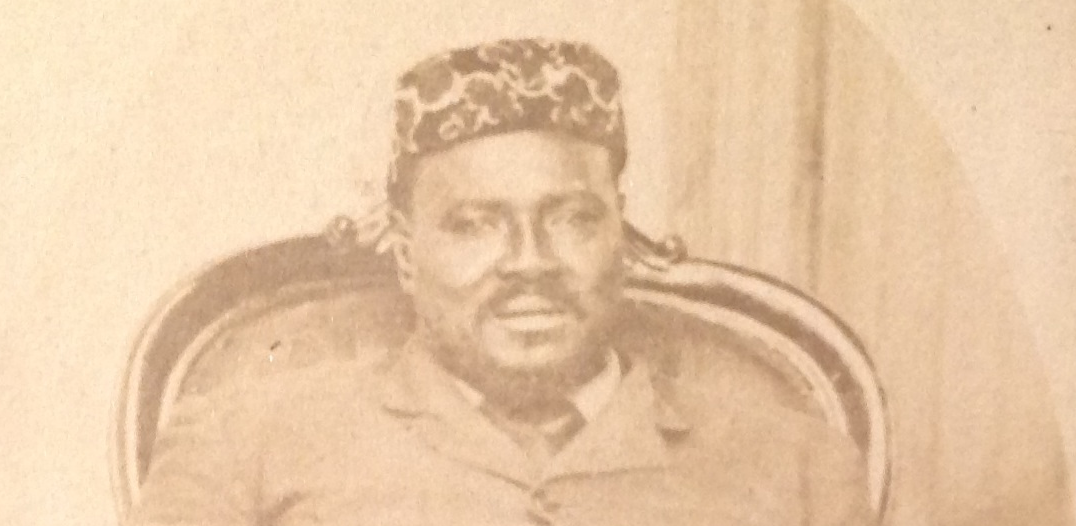

Zulu leaders photographed

- King Cetshwayo kaMpande (1826 – 1884) - Son of Shaka’s youngest brother, acceded to the throne in 1873 ruling until 1884. He attempted to avert conflict with the British. After the battle of Ulundi, the Zulu army was disbanded. Cetshwayo was captured at Ulundi on 4 July 1879 and taken to England via Cape Town. Cetshwayo returned to Zululand during 1883. He died the following year. The cause of death was recorded as a heart attack, but the British officer who examined him was of the view that his death was due to poisoning.

Carte-de-Visite format photograph by an unknown Cape Town based photographer. May have been taken by Crewes.

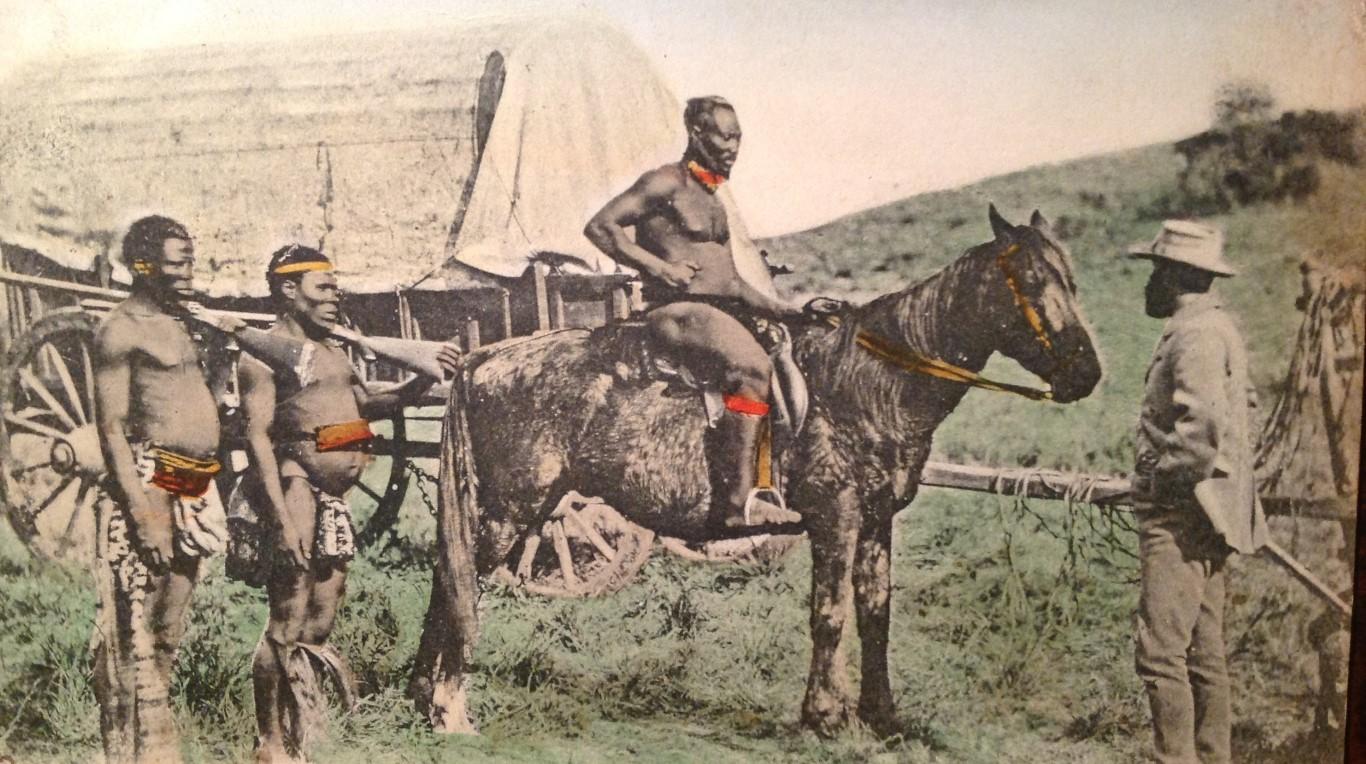

- Prince Dabulamanzi - Brother to Cetshwayo. Commander who led a group of Zulu warriors mainly during the Rorke’s Drift skirmish. He disobeyed instructions from his brother during the conflict. Described as one of the most daring Zulu commanders. He later surrendered to the British. Described as a good shot and rider.

Picture postcard showing Dabulamanzi on horseback. The card incorrectly describes it to be Cetshwayo. It is further suggested that it is Dunn on the right. The card was posted during 1904, but the image may well have been taken a number of years earlier. Card published by Sallo Epstein.

- King Dinuzulu - Cetshwayo’s eldest son – Succeeded his father as the last Zulu king. Another rebellion under his leadership resulted in the British withdrawing from Zululand. He was also exiled to St Helena from Zululand around 1889. He died during 1913 without returning to Zululand.

King Dinuzulu - Picture Postcard

- John Dunn - Cetshwayo had a lasting distrust of missionaries – he therefore turned to white traders for support. John Dunn was one such individual. They became personal friends. Dunn lived for many years as a chief and was a confidant to the king. Dunn also provided firearms to the Zulus. He had adopted Zulu customs, had a large number of Zulu wives and his followers numbered thousands (Knight, 1990). Dunn moved away with his followers from his territory in southern Zululand on the eve of the invasion. Dunn later sided with his countrymen.

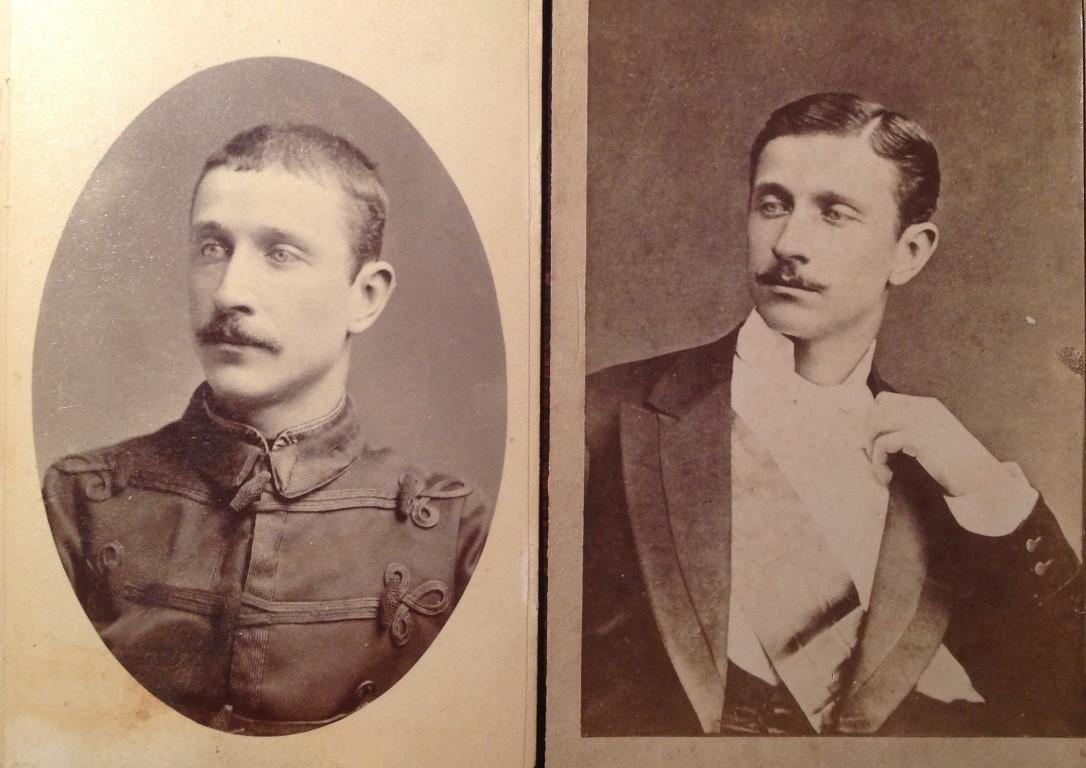

European royalty – Prince Imperial

Prince Louis Napoleon, commonly referred to as the Prince Imperial, was the only son of the exiled Emperor of France (Napoleon III) and the great-nephew of Napoleon Bonaparte. He completed his military training in Britain during 1875. Described as having an excitable and restless nature, he was viewed as a liability to those in charge of his safety. On 1 June 1879, the world received with shock the news of the death of a 22-year old British officer – The Price Imperial. He was assegaied 17 times.

Prince Imperial – Image of him in uniform was taken by Grahamstown based CJ Aldham (Circa 1879). Photographer of image on right unknown (Circa 1878).

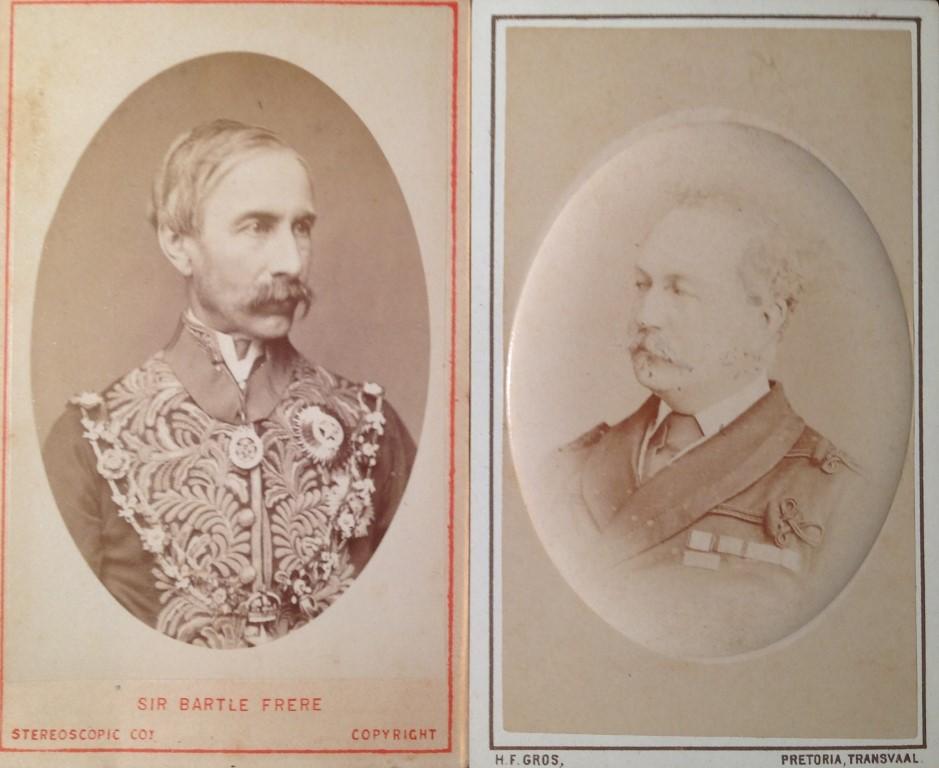

British leaders

- Sir Henry Bartle Edward Frere (1815 to 1884) – Became Governor of the Cape in 1877. He was the British Colonial Administrator who ordered the invasion of Zululand during which he acted largely without the support of the British government.

- Maj General Sir William Bellairs - Colonel during the AZW and commander of the Colony’s eastern districts. He played an advisory role to Frere.

Frere, taken in London. The signature on the back of this card seems to be that of Frere himself – dated 14 Nov 1882. Right – Bellairs – taken by HF Gros (Circa 1880 – Pretoria)

Officers in the field

All the officers listed below formed part of the 1st Battalion of the 24th regiment, commonly referred to as the 1/24th. They were all killed in action in what became known as “the last stand” at Isandlwana.

Considering that these photographs were taken in Cape Town, it is safe to assume that some of the officers served in the Cape Frontier war of 1878, prior to them taking up their positions in Zululand a year down the line.

- Lieutenant Charles John Atkinson. Served with Anstey, Daly, Coghill & Hodson (see their photographs below) in the Mediterranean during 1874. He was almost 24 at the time of his death.

- Lieutenant Francis Pender Porteous (Jamaican) – Led a company of the 1st Battalion of the 24th regiment. He was commended for his musketry instruction. He also served in India prior to his duty in South Africa. Before 1879 he also served in a garrison based in King William’s Town. He was 31 years old at the time of his death.

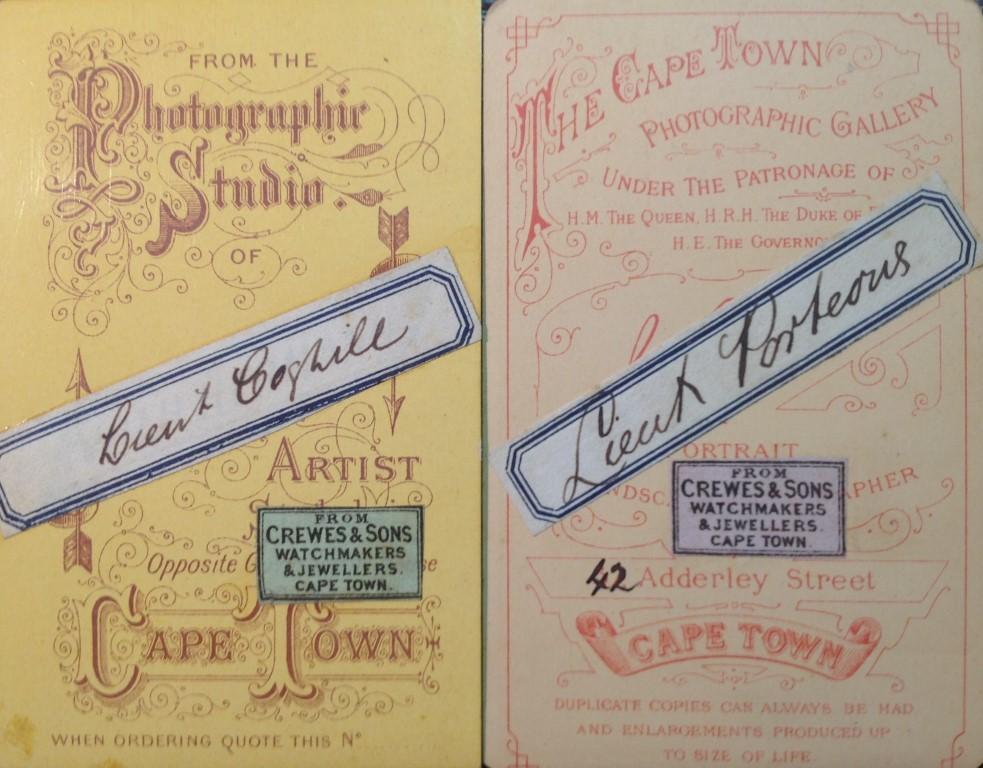

On left in uniform is Atkinson and on the right Porteous (By Crewes and Son)

- Lieutenant George Hodson (Irish). He was Colonel Glyn’s orderly officer. He was 24 at the time of his death.

- Lieutenant James Patrick Daly (Irish) – His body was found among about 60 British dead who made a “last stand” near the Banks of the Manzimnyana stream behind Isandlwana. His body was recovered by his brother, who also served in Zululand at the time and taken back to the UK – One of only a few British dead from the battle who were not buried where they fell. He was 23 at the time of his death.

On left is Hodson and on the right is Daly (By Crewes and Son)

- Lieutenant Neville Josiah Aylmer Coghill (Irish). He not only performed comical roles in theatre productions held in Cape Town, but was also a talented sketcher. The Royal Warwick theatre group drew members from both rank, file and officers. He became the Aide-de-camp appointment to Sir Bartle Frere during September 1878 but requested a transfer back to his regiment just prior to the AZW. He attempted to save fellow officer Lieutenant Melvill during the Isandlwana conflict while they were fleeing their pursuers. When the latter came off his horse whilst crossing the river, Coghill, who reached the opposite bank saw Melvill’s predicament and swam his horse to rescue Melvill. Coghill’s horse was killed by Zulu fire. They both made it to the opposite bank but did not survive the onslaught. Both officers received a posthumous Victorian Cross for their efforts to save the Queen’s Colour on the day. Coghill was 26 at the time of his death.

- Lieutenant Edgar Oliphant Anstey – He served in the Mediterranean prior to his duty in South Africa. His body was found among about 60 British dead - those who made a “last stand” near the banks of the Manzimnyana stream behind Isandlwana. He was 27 at the time of his death. His body was also taken back to England for burial there.

On left is Coghill and in uniform on right is Anstey (By Crewes and Son)

All the photographs of the officers above were produced by Cape Town based Crewes & Son. Crewes, who later went into partnership with van Laun, was also a jeweller and watchmaker.

Non-commissioned officers

There may be many AZW images still in circulation, but have become “lost” due to names of the sitter not being recorded or soldiers being photographed in civilian clothing which makes identification even more challenging. Four of the images of the officers above may have become lost if their names were not recorded on the back by the photographer Crewes.

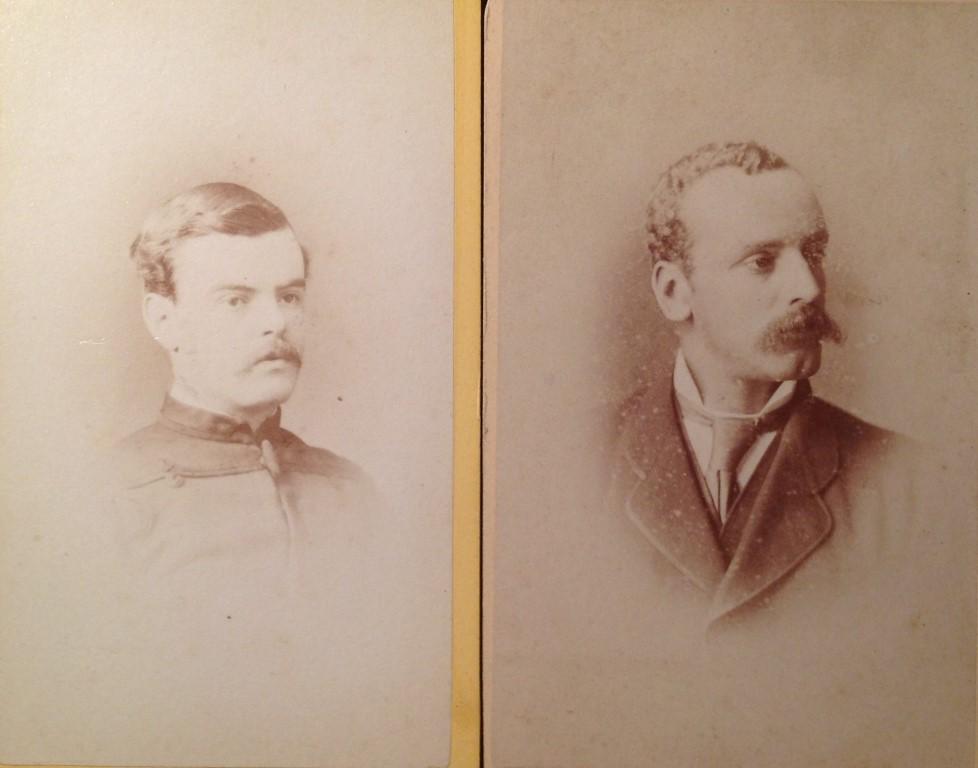

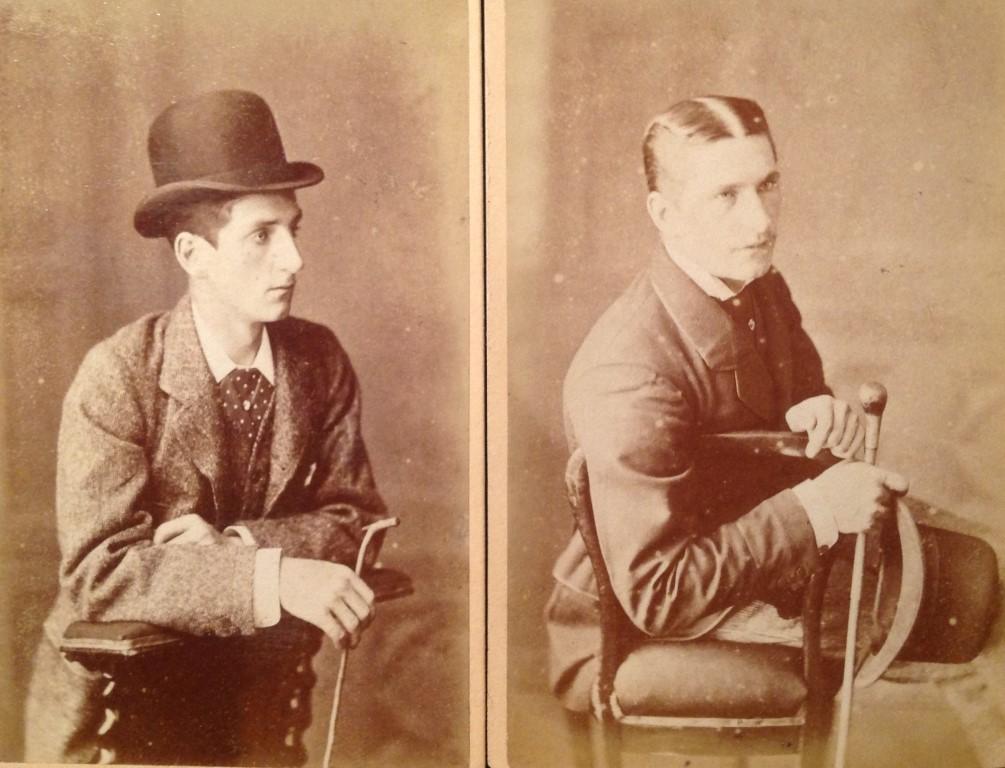

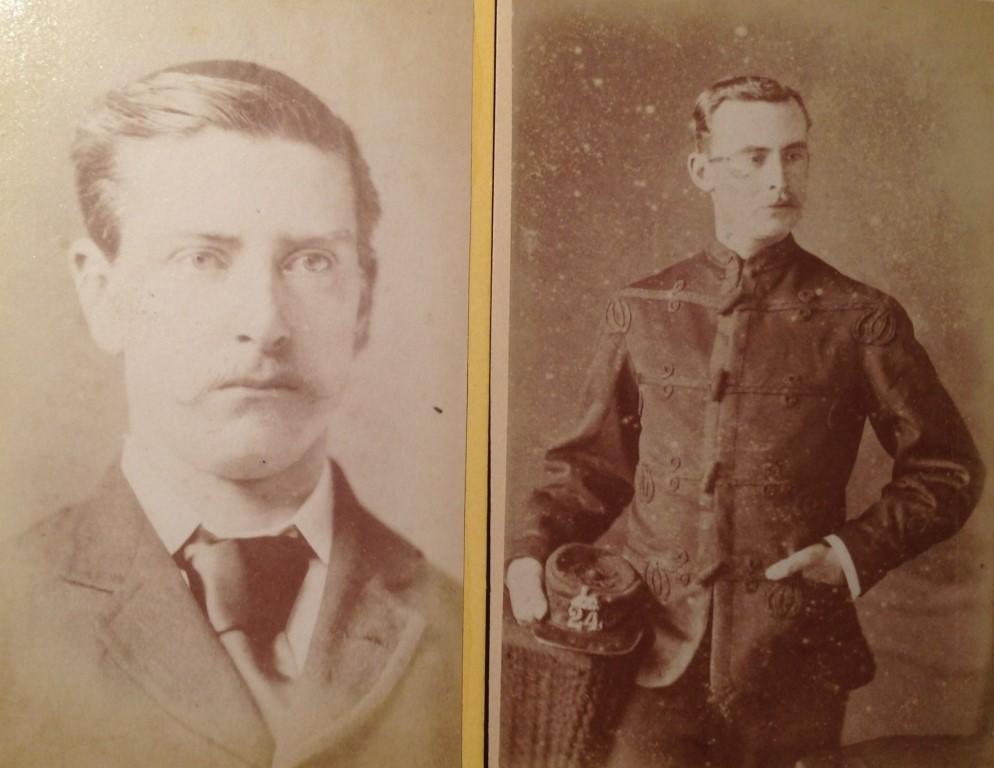

Noncommissioned officers. Carte-de-Visite photograph on left by Natal Stereo and Photographic company – GT Ferneyhough – Pietermaritzburg and on right a Carte-de-visite photograph by Kisch brothers based in Durban (Both Circa 1879)

Photographic commercialisation of the war

Various locally based photographers saw a commercial opportunity and positioned themselves in order to capture images of especially the British soldiers. Photographers that stood out were Charles F. Crewes & Sons (based in Cape Town), Kisch brothers (based in Durban), Ferneyhough (based in Pietermaritzburg) & CJ Aldham (based in Grahamstown).

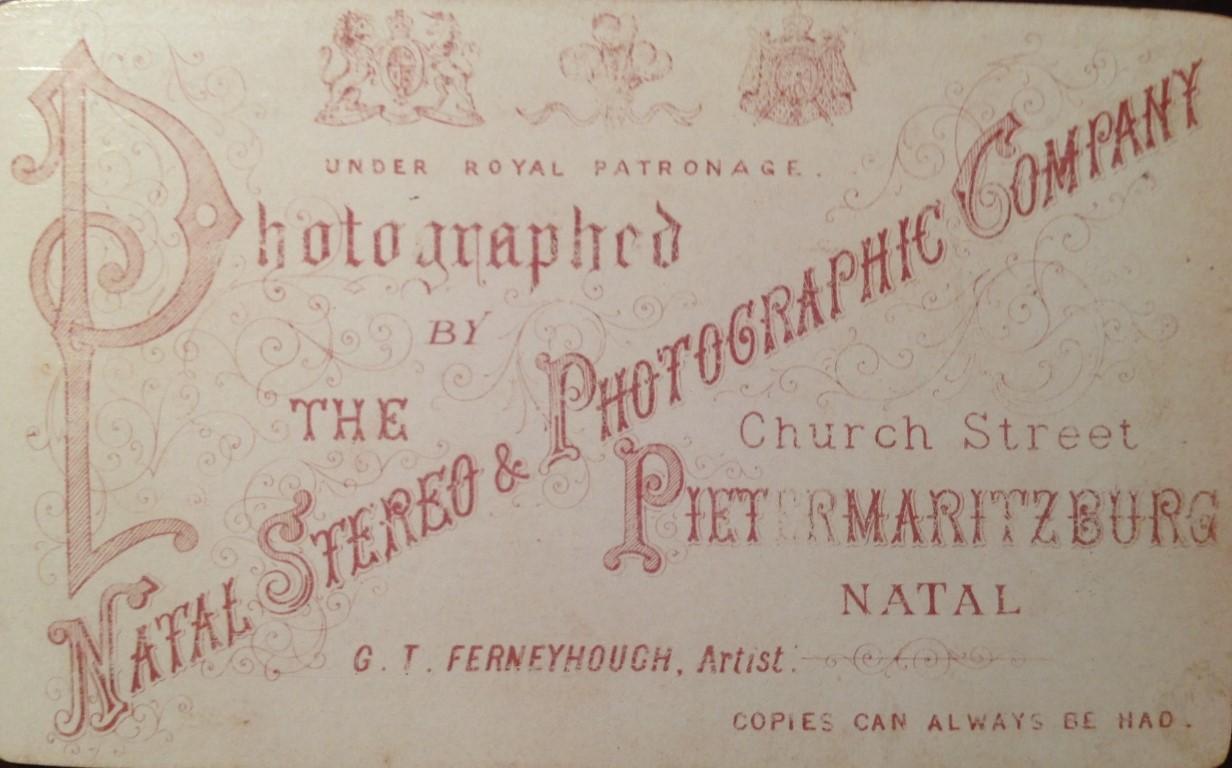

Back of the Natal Stereo and Photographic company carte-de-visite where GT Ferneyhough was the photographer

Crewes, seemingly managed to commercialise this event the best, as photographs produced by his studio were made available to the general population to purchase, especially those of the British officers who died during the conflict. It is not clear as to whether all these images were actually taken by himself at the Cape Town studio prior to the war, or whether he managed to reproduce images that were taken abroad before. The author however suggests that they were all taken in Cape Town. It has also been suggested that Crewes was on the SS Natal – the ship Cetshwayo was on, whilst travelling to England.

Interestingly, Crewes used pre-printed carte-de-visite stock of two of Cape Town’s better known photographers during that era, namely Samuel Barnard who operated The Cape Town Photographic Gallery from 37 Adderley Street and Wilhelm Hermann whose studio was based at 2 Roeland Street. This was not an all to uncommon activity amongst photographers. When a photographer ran out of card stock (carton backing on which photographs were pasted), they would purchase some stock from their competitors. These cards were largely printed in, and shipped from Europe during those years. Crewes simply pasted the name of the officers over Barnard’s or Hermann’s names and changed the address on Barnard’s cards from 37 to 42 Adderley street.

Card on left is Wilhelm Hermann’s carte-de-visite card stock, whilst card on the right is Samuel Barnard’s carte-de-visite card stock. Crewes would have bought up some of their stock in order to paste the images produced by him on the front. Crewes cleverly pasted the names of the Zulu war officers over the names of two the photographers.

The studio at 42 Adderley street had been in use since around 1855 and seems to have changed hands a number of times. First it was run by Frederick York followed by Arthur Green and later Frederick Mapp. In the 1880’s the studio was also known as The Colonial Photographic Saloon (probably whilst owned by Crewes).

Crewes also published a book titled “Table Mountain” during 1880. This book has been described as an exceptionally rare book on Cape Town.

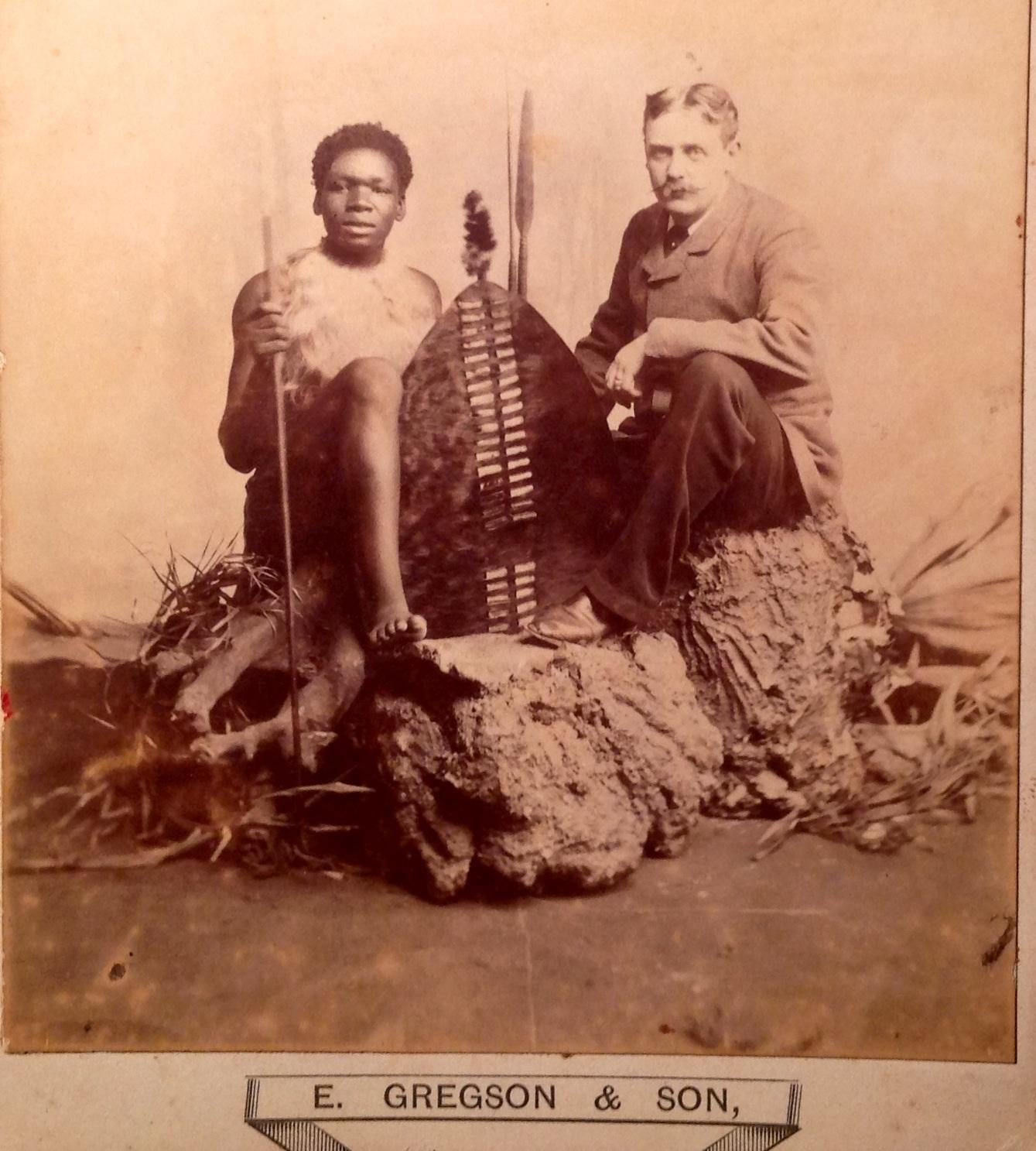

Post the war, Europeans just needed to have a photograph taken with a “Zulu warrior”. Although “E.Gregson & Son” has been recorded as active photographers in England, it is a possibility that they travelled to South Africa (more than likely Durban) in order to benefit from post war photographic opportunities.

Commercial photo by E. Gregson & Son believed to be based in Durban at the time (Circa 1882)

Ironically the serious collectors of AZW images are based in either England or the USA. The largest private AZW photographic collection is probably held by Ron Sheeley from North Carolina.

The author has a number of additional images of soldiers thought to be from the AZW period. Ongoing research is required to identify the men on these images.

Occasionally some AZW images still surface, mainly from old family photo albums, something that researchers and collectors alike keep a keen eye open for – even some 140 years down the line.

About the author: Carol is passionate about South African Photographica – anything and everything to do with the history of photography. He not only collects anything relating to photography, but also extensively conducts research in this field. He has published a variety of articles on this topic and assisted a publisher and fellow researchers in the field. Of particular interest to Carol are historical South African photographs. He is conducting research on South African based photographers from before 1910. He is also in the process of cataloguing Boer War stereo images produced by a variety of publishers. Carol has one of the largest private photographic collections in South Africa.

References:

- Bancroft, J.W. (2004). Rorke’s drift – The Zulu war, 1879. Jonathan Ball: Johannesburg.

- Barthorp, M. (1987). The Zulu War – a pictorial history. Blandford press: Dorset.

- Claassen, J. (2013). Photographers. (Click here for website)

- Danziger, D. (1978). The Zululand Campaign – Looking at South African history. Macdonald: Cape Town.

- David, S. (2005). Zulu – The heroism and tragedy of the Zulu War of 1879. Penguin Books: London.

- Fabb, J (1987). Africa – The British empire from photographs. Batsford: London.

- Featherstone, D. (1992). Victorian Colonial Warfare – Africa. Cassel: London.

- Gon, P. (1979). The road to Isandlwana. AD Donker: Johannesburg.

- Knight, I. (1990). Brave Man’s Blood – The epic of the Zulu war, 1879. Greenhill books: London.

- The Killy Campbell Africana Library based in Durban, not referred to by the author, holds a large collection of Zulu war images.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.