Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

The Governor Sir Philip Wodehouse imported an engineer of repute, Mr John Bourne, whom he had encountered in his previous posting in Demerara (now Guyana), where Bourne had saved the colony a large amount of money. The intention was to appoint him as Colonial Railway Engineer, but until there was a public railway for him to control there wasn't much for him to do. He toured the Colony to check out possible opportunities. His most far-reaching recommendation was that the government should plant forests of bluegums to provide timber for fuel, instead of importing Welsh coal to run the locomotives.

The obvious major route was to extend the Wellington line to Tulbagh and Worcester, and this alignment was informally approved by a select committee. Some work on the grading was done to keep the navvies from the original works employed, but in 1866 the government changed, and the Responsible and the Anti-Progressives Parties put a stop to railway construction - mainly because they felt that if country developed, they would lose their seats. Bourne's job opportunity was abolished and he returned to England. His lasting contribution to the Colony was a project he took on while kicking his heels - he stabilised the new lighthouse on Roman Rock which was about to collapse. The granite skirt which he suggested has ensured that the light is still in service today.

However there was steady pressure to extend the Wellington line and an 1868 governmental select committee recommended that railway construction be continued using departmental and convict labour. The official change of heart was not purely on a whim - some bright stones had been discovered in the Northern Cape and suddenly there was a rush of immigrants, bound for the diamond fields. The decision was taken to form the Cape Government Railways - and to head up the new enterprise, who better than the tough, competent and experienced former Chief Engineer of the Cape Town Dock and Railway Company - William George Brounger.

William Brounger (DRISA Archive)

Brounger accepted the invitation and returned to the Cape in 1871, but at the time there were still no government railways in the Western Cape. So for the first four years he was stationed in the Eastern Cape. Here routes to the diamond fields were also on the move, and there was tremendous haste to build links from Port Elizabeth and East London to Kimberley. By now his son was in a position to assist him and together they planned and surveyed these routes.

Responsible Government finally was granted to the Cape, and the first Prime Minister, John Molteno, who was the MP for Beaufort West, and was an ardent fan of railways - particularly if the main line to the North passed through his constituency. In 1874 the Government succeeded in buying out the Cape Town Railway and Dock Company for £773,000. The great push forward was about to begin.

The Gauge Dispute

The first railway was constructed to the English standard 4ft 8½-inch gauge. This was considered by many to be too broad to take the line through the mountains. Some advocated 2ft 6in; others including the embittered Scott Tucker suggested that only a light rail would work on the plateau.

Considerable debate ranged around an appropriate gauge for South African conditions and Brounger eventually put his foot down and standardised at 3ft 6inches, as had been successfully adopted in Canada and Norway. In later years, as modern construction techniques allowed curves to be relaxed, the narrower gauge would be regretted because it limited speed, but at the time it was a reasonable decision.

Brounger attracted a group of keen young engineers to carry out the field work while he directed strategy and operations from Cape Town. He had left able lieutenants in the Eastern Cape; Schmid and Slessor on the East London line and Devonshire Scott on the Midland system. The talented Wells Hood was put in charge of construction on the Western System.

Thomas Bain

But for the first difficult stretch through Tulbagh Kloof, Brounger needed an experienced expert; someone to keep the grades down, keep the curvature low, and to carry out substantial and safe earthworks at a reasonable cost. For a mountain pass, who better than the local expert, Thomas Bain? In 1873 he was at the height of his career, having just completed the Tradouw and Robinson Passes. Railway engineering must have been an interesting change, and he had a comfortable farmhouse in which to house his family. He had found the line for the road through the Kloof in 1855, and his railway line followed this alignment. He had to do without his usual convict labour, and initially the work was done by men from the missions at Genadendal and Zuurbraak, but by 1874 Brounger's recruiting drive had clicked in and he had about a thousand navvies at his disposal. Bain's work was not only the usual model of efficiency but also the route was spectacular. Photographs of the Blue Train passing through the Kloof were used for years afterwards on SAR&H publicity material to advertise the delights of rail travel in South Africa.

Blue Train in Tulbagh Kloof (DRISA Archive)

Bain however chose not to remain with railway work, and returned to the Roads Department, and to further triumphs.

Into the Karroo

The entrance to the Breede Valley had now been successfully negotiated, and the line reached Worcester in June 1876. For a couple of years trains would overnight at Worcester and the passengers would sleep at Frieslich's Hotel before re-embarking in the morning for the railhead where coaches would be waiting to carry them on to the diamond fields.

The question was now how to get across the next line of mountains and into the Karroo. An old surveyor cum engineer from Namaqualand, Richard Hall, had been engaged some ten years before to find a route up to the plateau. He had discarded Michell's Pass as too difficult and the Hex River as impossible without a three-mile long tunnel. The only feasible line as he saw it was through Cogman's Kloof to Montagu, then on to Ladismith, and then back along the Touws River valley to the present town of that name, and then on into the interior. It was obviously a most roundabout and undesirable location.

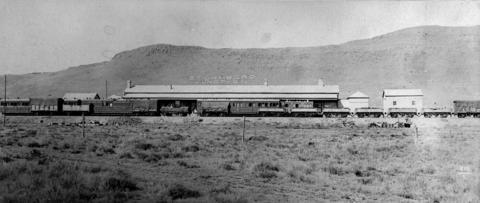

Wells Hood had other ideas. He too gave up on Michell's Pass, and one wonders whether, if Bain had been with him, he would have looked closer at this fairly obvious route. But the residents of the Bokkeveld did not press him, while at the end of the Karroo, Molteno beckoned. So Wells got out his survey boots and tramped in the mountains behind Worcester and came back triumphant. He had found a location where the grades were acceptable and the tunnelling relatively simple. And so, early in 1877 the railway reached Montagu Road, which we now call Touws River.

Touws River Station Buildings in 1895 (DRISA Archive)

By 1878 the line had reached a siding called Buffels River, which was renamed to avoid confusion with the Buffalo River in East London. Eventually it was named Laingsburg after the Commissioner for Crown Lands, John Laing. There were huge celebrations - including a cricket match - when the Governor opened the service to Beaufort West in February 1880. The survey as far as the Orange River was completed by the end of 1883 and at the same time the rails reached De Aar.

Laingsburg Station Buildings in 1895 (DRISA Archive)

Brounger the Manager

The Cape Colonial Railways flourished under Brounger's guidance. Until 1880 he was responsible not only for the development of all three systems, but also for the organisation of the operations. He then handed over the administration side to a General Manager, W.C.B. Elliot. In 1877, when Touws River was the railhead, over 600,000 passengers were carried on the Western Cape System alone. Over 2000 immigrants had been recruited to man the workshops, operate the trains and construct the works.

However construction was not simply a case of "Press on regardless". Research and innovation were regarded as an essential in the unfamiliar environment, and Brounger introduced steel rails as soon as they became available to replace the original wrought iron, which wore away rapidly in the harsh surroundings. Sleepers, which were liable to rot and be attacked by insects, also received attention, and after trying different timbers and treatments he settled for stinkwood, until Australian jarrah could be imported.

A new Cape Town railway station building and head office was built in 1876.

Cape Town Main Station Building 1876 (DRISA Archive)

James Logan

As Fred Harvey had found a gap, catering-wise, on the Atchison Topeka and Santa Fe, so did an impecunious young Scotsman named James Logan make a killing on the Cape Railways. He began as a porter on Cape Town station, and worked his way up. Within two years he was superintendent of the section between Matroosberg and Prince Albert Road. He bought the hotel at Touws River and realised there was money to be made in the provision of refreshments to passengers. Under somewhat dubious circumstances - the contract was awarded without calling for tenders or being approved by Cabinet (not the last time that ploy would be used in the country) - he obtained the monopoly for running all refreshment rooms on the railway system, entered parliament and along the way established the oasis of Matjesfontein.

Portrait of James Logan

Matjiesfontein in the 1890s

The Eastern Cape

The folk in the Eastern Cape always felt they got a raw deal, but in most of their ambitions they were divided as petty regional jealousies got in the way of progress. Thus Grahamstown, the main town in the region at the time, didn't want Port Elizabeth to grow, and so when railways were mooted, it opposed the construction of a link from PE. It wanted its port to be at the Kowie, although the siting a harbour there had severe limitations.

So Port Elizabeth plumped for a line to Graaff Reinet via Uitenhage, and a private company was formed to finance and build the line. The Government however was flexing its muscles in preparation for a takeover and agreed to build the line as far as the Swartkops River. The first sod was turned by the Governor, Sir Henry Barkly in January 1872. Labour was a problem as no navvies were available, and Xhosas were hesitant to be engaged, apart from being completely unskilled. The private section of the line made little progress and was taken over by the Government in 1875. Uitenhage was chosen as the site for the Eastern Cape workshops. Steady progress was made with construction and by August 1879 Graaff Reinet was reached. Here work halted, as there was no easy way northward from Graaff Reinet, lying as it does in a bowl of mountains. (The link with the mainline would only proceed in 1897.)

Meanwhile a link to the diamond fields was imperative and construction began on Brounger's location, to Cradock via Addo, Alicedale and Cookhouse. Grahamstown now tried to get the line diverted to it, but it was too late and it had to be content with a branch line from Alicedale - a difficult little 57km route with three tricky tunnels. Much of the work further north was done by a competent contractor, Faviell, and Cradock was reached in November 1880. It was now decided to take the railway to the Free State border at Colesberg, which was reached in October 1883. At Naauwpoort a junction was built to allow an 111km link to the Western Cape System at De Aar.

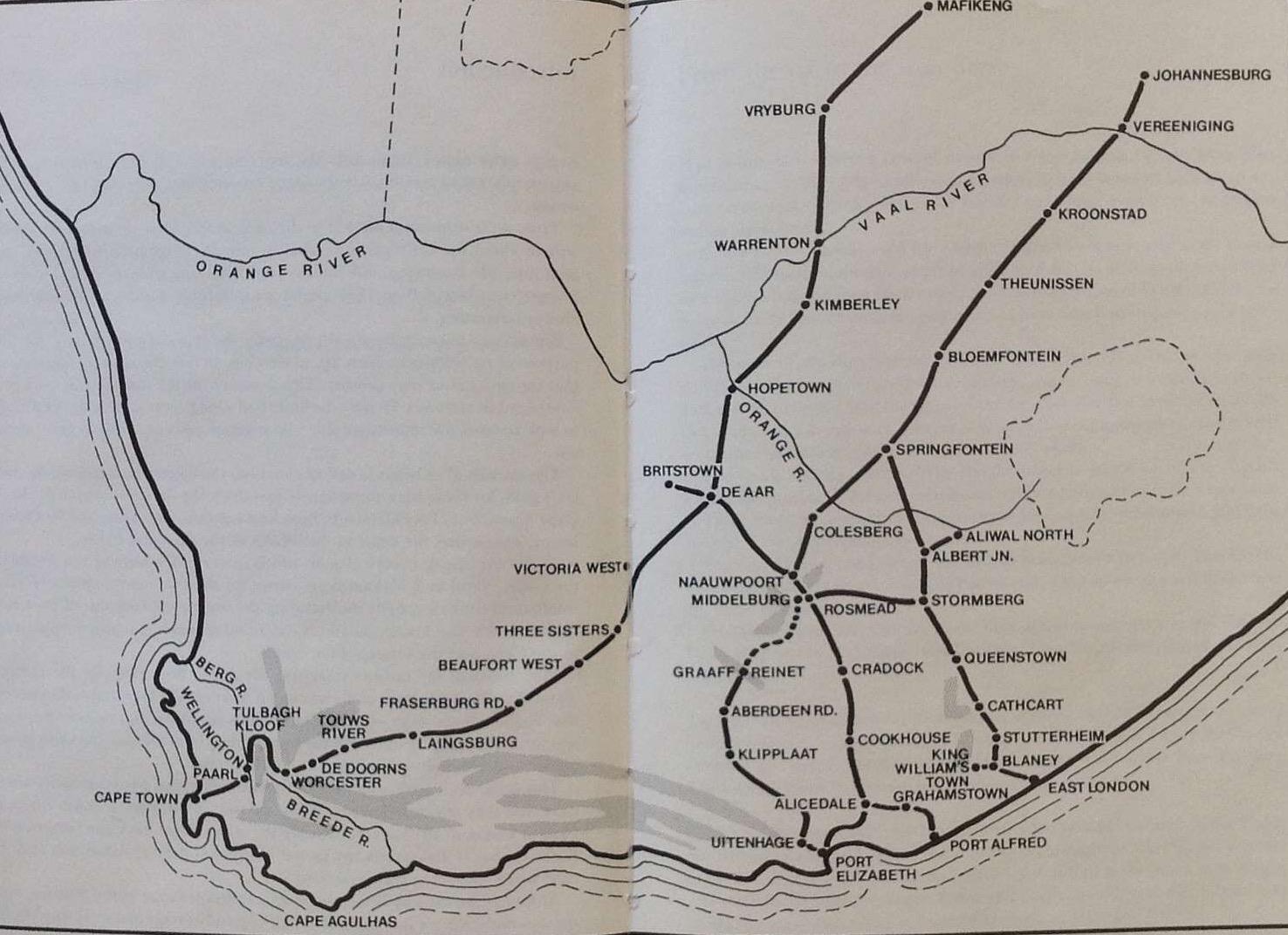

Main Lines of Cape Government Railways circa 1895 (Early Railways at the Cape)

The Eastern Line

In 1873 when the railway began, East London consisted of three little villages surrounding a viable port on the Buffalo River. It was decided to build a line to Queenstown, partly for economic reasons and partly to assist in the defence of the border. Labour was difficult. It was hoped that the expertise would be supplied by Belgian and German immigrants who would teach the local Xhosas some skills. The continental workmen were however unsatisfactory, and were replaced by British immigrants. Nevertheless between 1000 and 2000 indigenous people were employed at any one time and progress was good - except when disrupted by faction fights and border wars. Construction was halted between August 1877 and April 1878, for the last of the border wars, but Queenstown was reached in 1880.

The Stormberg Mountains were a really formidable hurdle to further progress, but they had to be crossed if the system was to link up with the Midland railway. There was an additional incentive. Coal had been discovered at the village of Molteno, and although it was of low grade it would make a considerable difference to the economics of the line.

Just north of Molteno a line was built from Stormberg junction via Steynsburg to Rosmead on the Midland system linking the two Eastern Cape systems. The main line continued north to Burgersdorp where it split, one arm going to Aliwal North and the other crossing the Orange at Bethulie and eventually linking with the main Bloemfontein Line at Springfontein.

Stormberg Railway Station (DRISA Archive)

Brounger Junction

The Midland and Western Cape systems were linked at De Aar on 31st March 1884 and further progress north for both systems would be by means of a single line towards Kimberley. Some years later De Aar would be the springing point for the line to Upington and Windhoek but from the beginning this was the railway junction in South Africa about which few rail travellers have happy memories. In the early days it was an even more dismal place and its reputation was not enhanced by the faction fight which took place on Christmas day 1883, when rival construction gangs from the two systems clashed and 60 men died.

There were calls to name the meeting place of the Western and Eastern Cape systems "Brounger Junction" in honour of the father of the Cape railways, but perhaps the distinguished engineer preferred not to be associated with the dreary sun-baked rail town. In any event the name did not stick and reverted to De Aar. But by this time the begetter had done his work. He retired and returned to England in 1883. Shortly after his return he presented a paper entitled "The Cape Government Railways" to the Institution of Civil Engineers for which he was awarded the prestigious Telford Medal. He died in 1901.

By any standards Brounger was an engineer of distinction who made a great contribution to the development of South Africa. Many men were knighted for less. It's a pity his name is not better remembered.

Tony Murray is a retired civil engineer who has developed an interest in local engineering history. He spent most of his career with the Divisional Council of the Cape and its successors, and ended in charge of the Engineering Department of the Cape Metropolitan Council. He has written extensively on various aspects of his profession, and became the first chairman of the History and Heritage Panel of the South African Institution of Civil Engineering. Among other achievements he was responsible for persuading the American Society of Civil Engineers to award International Engineering Heritage Landmark status to the Woodhead dam on Table Mountain and the Lighthouse at Cape Agulhas. After serving for 10 years on SAICE Executive Board, in 2010 he received the rare honour of being made an Honorary Fellow of the Institution. Tony has written manuals, prepared lectures and developed extensive PowerPoint presentations on ways in which the relationship between municipal councillors and engineers can be more effective, and he has presented the course around the country. He has been a popular lecturer at UCT Summer School and has presented five series of talks about engineers and their achievements. He was President of the Owl Club in 2011. His book "Ninham Shand – the Man, the Practice", the story of the well-known consulting engineer and the company he founded, was published in 2010. In 2015 “Megastructures and Masterminds”, stories of some South African civil engineers and their achievements was written for the general public and appeared on the shelves of good bookstores. “Past Masters” a collection of his articles about 19th century South African Engineers is also available from the SAICE Bookshop.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.