Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

Carol Hardijzer is passionate about South African Photographica – anything and everything to do with the history of photography. He not only collects anything relating to photography, but conducts extensive research in this field. He has published a variety of articles (click here to view) on this topic and is currently doing research on South African based photographers from before 1910. He has one of the largest private photographic collections in South Africa.

I recently came cross Carol's article on missionary photography in South Africa (click here to view). Intrigued by the topic, I decided to dig more into this fascinating, but rarely examined aspect of missionary activities in South Africa by speaking to him. The interview below is the result.

Daluxolo Moloantoa (DM): Missionary photography forms a significant part of the history of photography in South Africa. How and why did it become so important?

Carol Hardijzer (CH): Indeed, missionary photography forms a significant part of South African history, yet the value thereof on our cultural history has still not been fully understood or exploited. Many research opportunities still exist in this field.

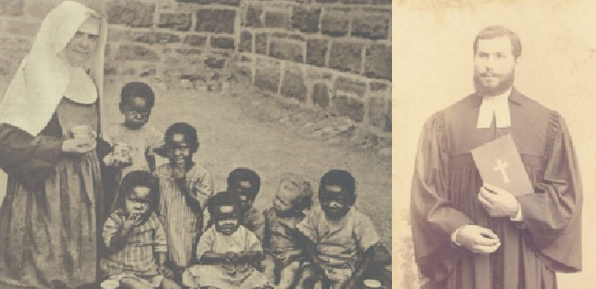

Within the South African context, it could be argued that the most comprehensive photographic evidence of our diverse cultural history would be those produced by the missionaries who established themselves in the vast expanses of South Africa. The key purpose for the amateur missionary photographers was to publicize their religious work with the local inhabitants in order to bring it to the attention of their principals and supporters in Europe.

We do not know how many missionary photographers have been active in South Africa since the commercialization of photography around the 1850s. Unlike commercial photographers, who focused more on studio work or scenic views, the missionary photographers, who were largely based outside the larger cities, focused their attention on the local inhabitants they interacted with. What is certain is that missionaries were natural visual recorders of their surroundings and in doing so contributed vastly to the early visual history of South Africa.

Some of the primary reasons why photographic works produced by missionaries remain important include:

- Their photographic work gives the viewer an insight into the daily lives of the local inhabitants in the rural areas – something the professional photographer generally did not prioritize;

- It provides for a perspective as to how the missionaries adapted to their environment;

- They compiled valuable visual records – today of historical significance;

- The majority of their photographs were not produced for commercial reasons;

- The photographs were not staged (maybe posed yes) and therefore gives the viewer a more realistic perspective of daily life and activities that the missionaries were surrounded by;

- Photographic work produced by missionaries is scarcer in that their work is not as easily identifiable compared to that of the commercial/professional photographers who made their work identifiable by applying their names to the various photographic formats during those years.

Missionaries based in South Africa were intrigued by the ethnical composition of society. Their curiosity with the indigenous African way resulted in many photographic images being taken to share with Western Society, many of them in the format of magic lantern slides in order for the images to be projected at gatherings.

DM: Who were the main figures behind the practice?

CH: Considering the proposed definition of Missionary Photography above, both the missionaries and travelling professional photographers. It certainly did not form part of any missionaries’ day task to photograph the local inhabitants. Those who did, did so for reasons already stated or due to their personal interest in photography – they remained amateurs. This is why for some missionary regions more photographic evidence would be found compared to other.

An interesting story: One Methodist missionary, Frederick Lewis, returned to London during 1911 due to his long list of shortcomings as a missionary. He was however complimented as “a capital photographer” by his principles who were so critical of him in the first place. In Surviving the Lens (Stevenson & Graham-Stewart) a picture taken by Lewis appears on page 119.

DM: What are the earliest known examples of missionary photography in South Africa?

CH: This is an aspect that still requires further research. The bulk of photographic images produced by missionaries however date from the 1880s to the 1940s. It has been suggested that South African missionary photography probably predates that of many other countries as images from around the 1860s are known to exist. This is confirmed in The Face of the Country (by Karel Schoeman) which shows an image taken by the photographer FAV York, who formed part of the Prince Albert tour. This image is of a formal group in front of the thatched buildings of the Weslyan mission station of Lesseyton (Eastern Cape - Northwest of Queenstown) (Page 50). This photograph was taken on 17 August 1860.

James Cameron, a Scotsman, has been recorded as a Cape Town based photographer during the 1850s. He left for Madagascar as an artisan missionary during 1863. It can therefore be safely assumed that he not only continued his art as photographer whilst in Madagascar, but that he also took missionary related images whilst in South Africa during the 1850s and early 1860s.

DM: Being an enthusiast, and having observed the evolution of missionary photography in South Africa, are there any thematic patterns that you have observed over the period in which the practice took place?

CH: With their Eurocentric masks, missionaries entered communities either as constructive participants or sometimes as antagonists, but almost always as curious observers of the indigenous ways. For reasons both practical and religious, missionaries were dedicated correspondents, diarists and record keepers.

There was significant curiosity value back home around the indigenous people. This made for good photographing opportunities. A strong underlying cultural and anthropological stance can therefore be seen in much of their work.

DM: In hindsight, what do you think was the major motivation for missionary photography in South Africa?

CH: Their needs for creating photographic images were diverse. From creating an argument to their principles about the scale of the evangelistic task at hand to propaganda (mostly presented from an unintended Eurocentric point of view) - or simply for personal reasons in order to communicate back to family based in the country they originated from.

DM: Having covered the length and breadth of the country, where was missionary photography most significant and with which denomination amongst the churches was it most prevalent?

CH: This is an aspect that still requires much research. In order to be able to determine this, missionary societies, or their libraries that hold their archives would be the ideal sources to be consulted. Images produced by, or about missionaries, from all over Europe are known to exist. Whilst much research may have been done to date on missionary activity, the photographic dimension thereof has been neglected.

DM: In the totality of time and space, what is the legacy of missionary photography in the larger narrative of South African photography?

CH: Photographs produced and collected by missionaries left us with a richer visual history. Without the visual evidence produced by them, both missionary and the cultural history of our local population by and large would have been based purely on documented narratives. Images that have survived fill those gaps in our knowledge base as to what “things were like” during missionary activities in South Africa, especially prior to the 1920s.

Daluxolo Moloantoa is a freelance writer and journalist. After being awarded a scholarship by the Sowetan newspaper and Herdbuoys McCann-Erickson advertising agency he studied copywriting at the AAA School of Advertising in Johannesburg. After a brief period working in the advertising industry, he went on an exchange programme to England and studied for a Community Media Certificate with the Community Volunteer Service Media Clubhouse in Suffolk. He became an arts journalist with Ipswich-based youth magazine IP1 and began covering South African arts-based news for London-based South African publication The South African as well as Cape Town charity magazine The Big Issue. On his return to South Africa he became arts contributor to a number of local publications. In 2015 he won the Academic and Non-Fiction Association of South Africa (ANFASA) – Norwegian Foreign Fund Writers Award for his research project on missionary schools in South Africa. Visit www.gatewaystoanewworld.wordpress.com to see more of his work.

Carol Hardijzer is passionate about South African Photographica – anything and everything to do with the history of photography. He not only collects anything relating to photography, but also extensively conducts research in this field. He has published a variety of articles on this topic and assisted a publisher and fellow researchers in the field. Of particular interest to Carol are historical South African photographs. He is conducting research on South African based photographers from before 1910. He is also in the process of cataloguing Boer War stereo images produced by a variety of publishers. Carol has one of the largest private photographic collections in South Africa.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.