Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

Including Revised 1960s Alphabetical Directory of South African based Photographers & Studios (1846 to 1915) - Click here to download.

Shortly after the invention of photography, the camera was briefly referred to as a “Mirror with Memory”, whilst the resulting photographic image was initially referred to as a photogenic drawing.

1) Introduction

During the early 1960s, Doctor Arthur David Bensusan published the first and only record to date of South African based photographers between the period 1846 and 1900.

An updated version of this list has not been published for the past 57 years! Bensusan’ s 1963 list has been reproduced on ancestors.co.za, but sadly his work has not been acknowledged.

The author has made it his personal task over the past 25 years in updating the original Bensusan directory of photographers. In doing so, the vast Hardijzer Photographic Research Collection was established.

Other photograph collections that were established along similar lines by South African photo historians are the Killy Campbell (today housed at the Killy Campbell museum), Reverent Hopkins (today housed at the Cape Archives) and Bensusan (today housed at Museum Africa in Johannesburg) collections, but to mention a few.

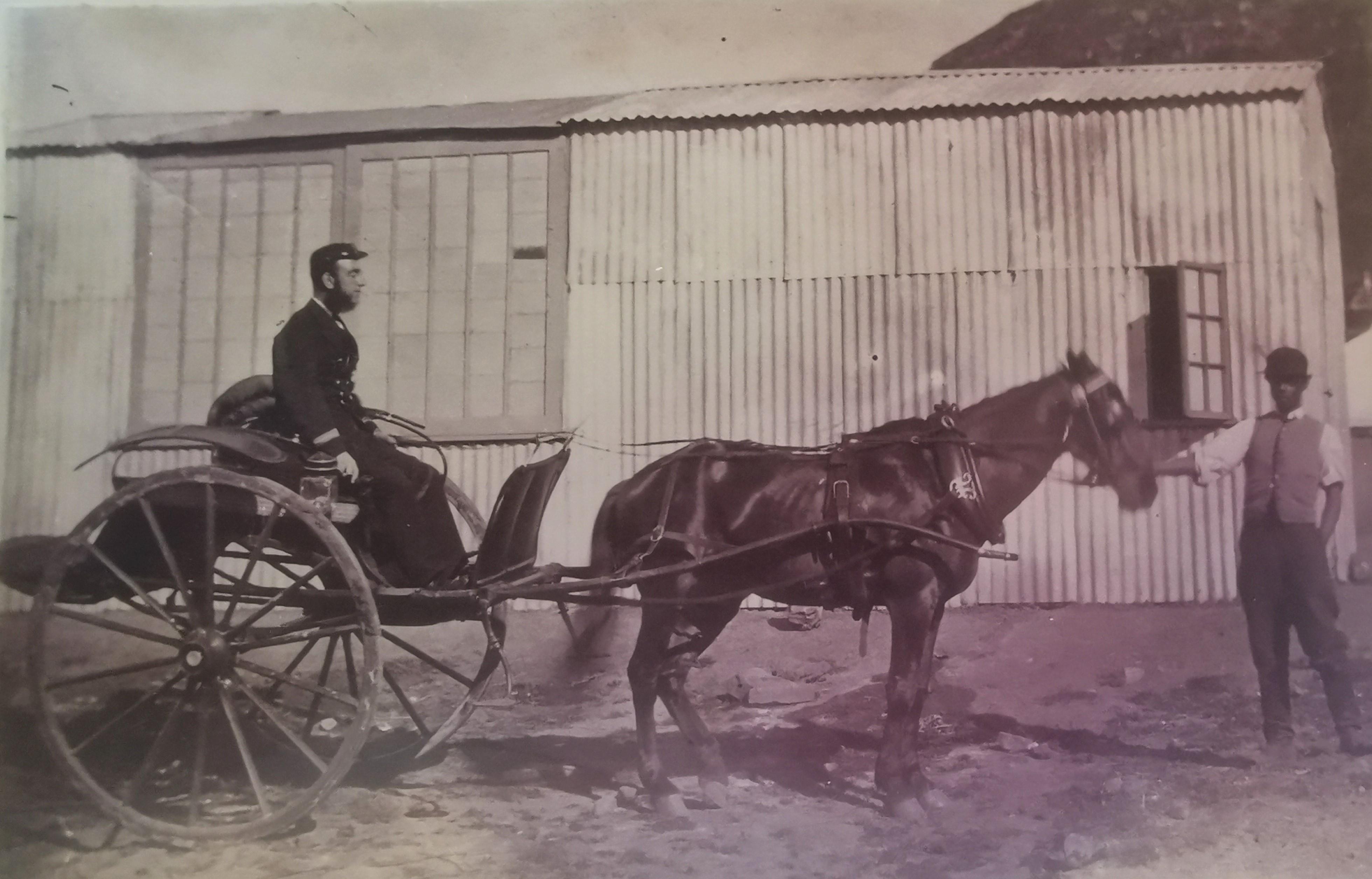

Simonstown – Inscription on image states: “Secretary Brown in his dog-cart plus Photographic Saloon – 1876”. The large window of this corrugated iron building was put in place to allow light into the photographic studio. It is not clear who the photographer was. It could either have been William Bremner or David Selkirk, both of whom were active as photographers in Simonstown at the time.

Fortunately, some original photographic work of photographers from this era have also survived and are being effectively curated. Some examples include:

- Ambrose Lomax : Molteno based photographer – Housed at Cape Archives;

- Arthur Elliot: Cape Town based photographer – Housed at Cape Archives;

- Hugh Exton: Pietersburg (Polokwane today) based photographer - Housed at Polokwane local museum;

- James Gribble: Paarl based photographer – Housed by Drakensteinheemkring;

- Joseph & David Barnett: Johannesburg based photographers – Housed at Wits University;

- William Roe: Graaff-Reinet based photographer – Housed at the Graaff-Reinet museum.

The Johannesburg based Transnet Heritage Library Photo collection also houses a vast photographic collection of images captured by photographers in the employ of the then South African Railways and Harbour Publicity section (See www.drisa.co.za).

Another significant photographic collection is housed at the McGregor Museum in Kimberley. Irish born Alfred Martin Duggan-Cronin’s work also forms part of this collection. His photographs were mainly produced after 1915, resulting in his name not being recorded on the attached directory.

From the outset it needs to be stated that the revised directory is incomplete and that it remains work in progress for the author. This may well attract criticism from academic purists, but by publishing the revised directory, the intention is to potentially receive additional snippets of information from genealogists, fellow researchers or family members of some of these early photographic pioneers.

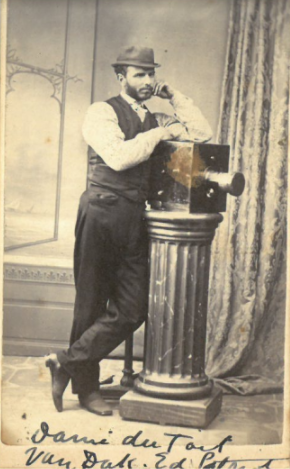

Carte-de-Visite image by unknown photographer of Daniel Francois du Toit editor of “The Afrikaans Patriot” which was established in Paarl (Circa 1878). He also went by the nickname “Oom Lokomotief” (Uncle Locomotive). Of significance is the camera Danie is leaning on. The camera, used as a studio prop, in all probability belonged to the newspaper company.

Research on early photographers is much better entrenched abroad compared to South Africa. Some examples include Ron Cosen’s British directory of Victorian Photographers (see www.cartedevisite.co.uk) and Sandy Barrie’s Australians Behind the Camera. Directory of Early Australian Photographers, 1841-1950. Fellow photo historian, Australian Marcel Safier, has also been a passionate contributor to these directories.

Ironically, the majority of research on South African photographic history currently seems to be conducted by foreign academia.

The two most significant sources produced on South Africa’s photographic history by South African citizens were by Bensusan (1966) and Bull & Denfield (1970). During the 1960s and 1970s important contributions on South African photographic history were also made by amongst other, Anna Smith, Brian Warner, Nat Cowan, Karel Schoeman and B Spencer. Their contributions were made to societal newsletters such as the Africana Notes and News.

Other significant research/publications on South African photographic history include the work by de Beer & Barker (1992); Schoeman (1996); Stevenson & Graham-Stewart (2001); Dietrich & Bank (2008); Malherbe (2014) and Rizzo (2019).

Where did South Africa’s photographic history start? The two paragraphs to follow provide a brief reflection on where it all started for South Africa.

Hand coloured Carte-de-Visite format photograph captured by Cape Town based Lawrence brothers (Circa 1876). A studio appointed colourist would have hand coloured the image afterwards. In some instances the photographer may have been the colourist themselves.

2) South Africa’s pioneer experimental photographer – Charles Piazzi Smyth

The introduction of photography to South Africa has been attributed to various people, but it is generally accepted that one of the earliest enthusiasts was Sir John Herschel (1792-1871), who spent four years at the Cape whilst conducting a survey of the southern sky. On hearing of Frenchman Daguerre’s invention, which later was to be called photography, Sir Herschel was able to invent, within a very short timeframe, his own process by using sensitised paper. This he described in a letter during addressed to Sir Thomas Maclear during July 1839, the director of the Royal Observatory in Cape Town.

Influenced by Sir John Herschel was the twenty-year-old assistant to Sir Thomas Maclear, Charles Piazzi Smyth. Young Smyth, an Italian born British astronomer (1819 - 1900), was based at the Cape Observatory for 11 years (1835 to 1846).

Charles Piazzi Smyth (1824- 1900) – Portrait painting of South Africa’s first experimental photographer (photograph extracted from Wikipedia)

It is recorded that Smyth already tried his hand at producing photogenic drawings as early as 1839 in that Professor Brian Warner has found evidence in diary notes of the 13-year-old Mary Maclear (daughter to Thomas Maclear) where she stated that her and Smyth attempted their hand at “photogenic” drawings (unsuccessfully so) as early as November 1839.

In his ongoing attempt to capture images from 1841 onwards, Smyth used his own designed photographic equipment.

Busy with photography throughout 1842, the earliest of Smyth’s photographs, which were evidently not properly fixed, turned completely black. During his experimentation he photographed mostly the Royal Observatory (incidentally, the oldest known photographs of any observatory in the world) and of the garden which he himself had planted in the inhospitable soil surrounding the building at the confluence of the Salt and Liesbeeck rivers.

The oldest known experimental and most authentically dated photograph taken in South Africa (that has survived) was produced by this same enthusiastically curious Smyth during February 1843.

Today, some three dozen experimental photographs by Smyth are known to exist – mostly in possession of the Royal Society of Edinburgh (Warner, 1983).

3) Other South African photographic firsts

Countries, other than Europe, where commercial photography became entrenched prior to South Africa were Mauritius (1840); Australia (1842) and India (1843).

Significant also is that during 1851, Britain had some 51 photographers recorded, yet South Africa still had less than 40 active photographers recorded ten years later (1861).

Some significant photographic firsts for South Africa include:

- First South African born citizen confirmed to date to have become a commercial photographer was William Syme (born in Cape Town during 1824);

- The Calotype photographic process was first described in the South African Commercial Advertiser (22 January 1842);

- The first published advertisement for a Daguerreotype camera offered for sale in South Africa was placed by an immigrant Carel Junghenn during November 1843;

- It has been suggested that the first photographic portrait taken on South African soil was by Charles Piazzi Smyth of William Mann during 1843 – Mann referred to this image of himself as a “beautiful phiz”;

- The first recorded commercial photographer in South Africa was the Frenchman MJ Léger, who had made a sea voyage to India, taking with him a daguerreotype camera. During the return journey the ship, Hannah Codner, anchored at Algoa Bay (Port Elizabeth today) on 14 October 1846. Léger disembarked, intending at first to demonstrate his photographic skills while the ship lay at anchor. Legend has it that this is where he met William Ring, a local bookdealer and together they decided to set up South Africa’s first photographic studio in Port Elizabeth. After their considerable success, they proceeded to Grahamstown where an exhibition by Léger was described as “beautiful, wonderful and interesting”;

- Reference was made to the Cape Town’s first photographer as early as December 1844, in which German born Carel Sparmann was referred to as a “daguerreotype dabbler”. This was followed by a further published reference on 29 October 1846 confirming the first commercial photographer activity in Cape Town (by Sparmann), yet Sparmann’s first recorded photograph was only produced during April 1847. From this point onwards there was an ever-unfolding record of photographers electing to generate an income from this new art form – Also the starting point of the directory attached. None of the early Cape Town photographers however prospered.

- First outdoor event was photographed in the Cape on 19 May 1849;

- First panoramic image of Cape Town was captured by William Morton Millard during 1859 – he has been recorded as being an amateur photographer;

- First Carte-de-Visite camera used in South Africa was by Cape Town based Frederick York (February 1861). Arthur Green followed in his shoe steps shortly thereafter;

- First Cabinet Card format photograph was produced by Cape Town based Samuel Baylis Barnard (September 1867).

4) Bensusan’s initial list of photographers

In establishing the first catalogue, Bensusan obtained his information mainly from editorial and advertisement columns of various South African newspapers, various directories, almanac’s and year- books from between 1845 and 1900.

The approach applied by the author in expanding the Bensusan’s list was different in that it mainly entailed:

- Sourcing original photographs by the various photographers;

- Fellow researchers presenting evidence of previously unidentified photographers through their enquiries directed to the author;

- Photographs published on the internet.

When Bensusan published his initial list, containing some 607 entries, he stated the following around the completeness of the list:

It is by no means a complete list and no claims are made that all who practised the art of photography have been included… It is estimated that there may be a further hundred photographers who have still to be listed…

This same argument still holds true for the 2020 revised version attached.

The revised directory attached includes some 1673 entries, thereby expanding the Bensusan list by an additional 1066 photographers and/or studios. It is acknowledged that this significant increase is also due to the initial cut-off date applied by Bensusan (namely 1900), being extended by the author from 1900 to 1915.

The reason for this expansion is two-fold:

- To include photographers that were active during the Anglo-Boer war;

- To include photographers who used the Cabinet Card format photographs until around 1915s.

With ongoing research, the possibility remains that a further 100 photographers, photographer assistants and studios could still be uncovered and added to this revised directory. Literally 10 days prior to publishing the attached directory, whilst on a road trip, the author obtained a photograph of a Kimberley based photographer (H. Starkie – see image below) not previously identified.

Kimberley based Photographer H Starkey only identified as recent as September 2020 (Circa 1900)

A number of spelling errors occurred in surnames in the earlier years (in directories, newspaper articles, advertisement as well as on photographic stock cards) resulting in deductions that needed to be made in terms of the correct spelling of some surnames.

Whilst multiple photographic partnerships were established during this era, many have not been established sufficiently long enough to have traded under names other than those of the principle photographer who had established the photographic establishments, resulting in some photographers that may have been missed.

During this period, there were also a considerable number of itinerant photographers, many of whom would either have signed photographs produced by themselves by hand or not at all. Professional photographers were more inclined to have pre-printed card stock in hand or have a rubber stamp with their details engraved applied on the front or back of the image.

Additional information included in the revised directory includes crucial information such as full names, country of birth, each town where a photographer was active as well as name and address of studio where available.

Until at least the outbreak of the Anglo Boer war, relatively few photographers performed the art of photography on a full-time basis in that photography was only a secondary source of income to many. Primary careers followed by these photographers included, amongst other, medical practitioners, artists and colourists, coppersmiths, engravers, watch makers, furniture dealers, opticians, chemists, accountants, jewellers and even hoteliers. In search of generating an improved income, photographers also often travelled.

James Gribble – Paarl based photographer. Extracted from drakensteinheemkring.co.za

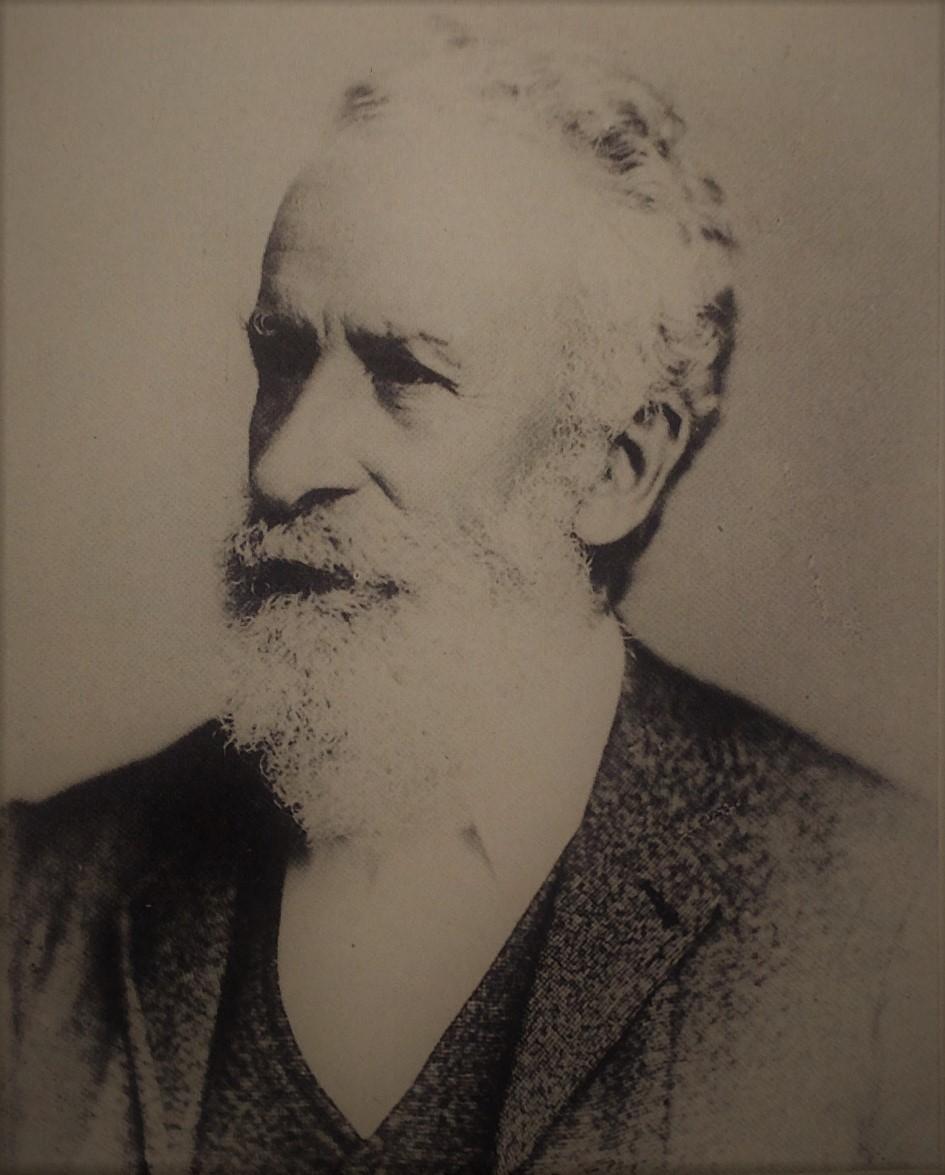

William Roe – Graaff-Reinet based photographer. Image reproduced from Secure the Shadow

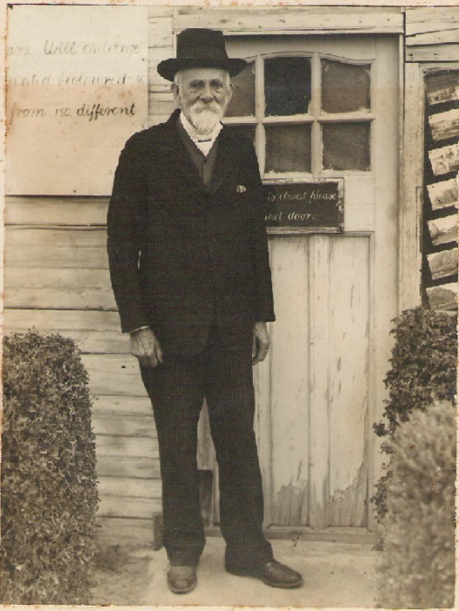

South African born Thomas Daniel Ravenscroft – Photographer who was based in Malmesbury (where he was born), Robertson, Somerset East, Hermanus & Villiersdorp. He was also a photographer to the Cape Colonial Railways.

Ambrose Lomax – Molteno based chemist and photographer – Circa 1910 (Image extracted from Wikipedia)

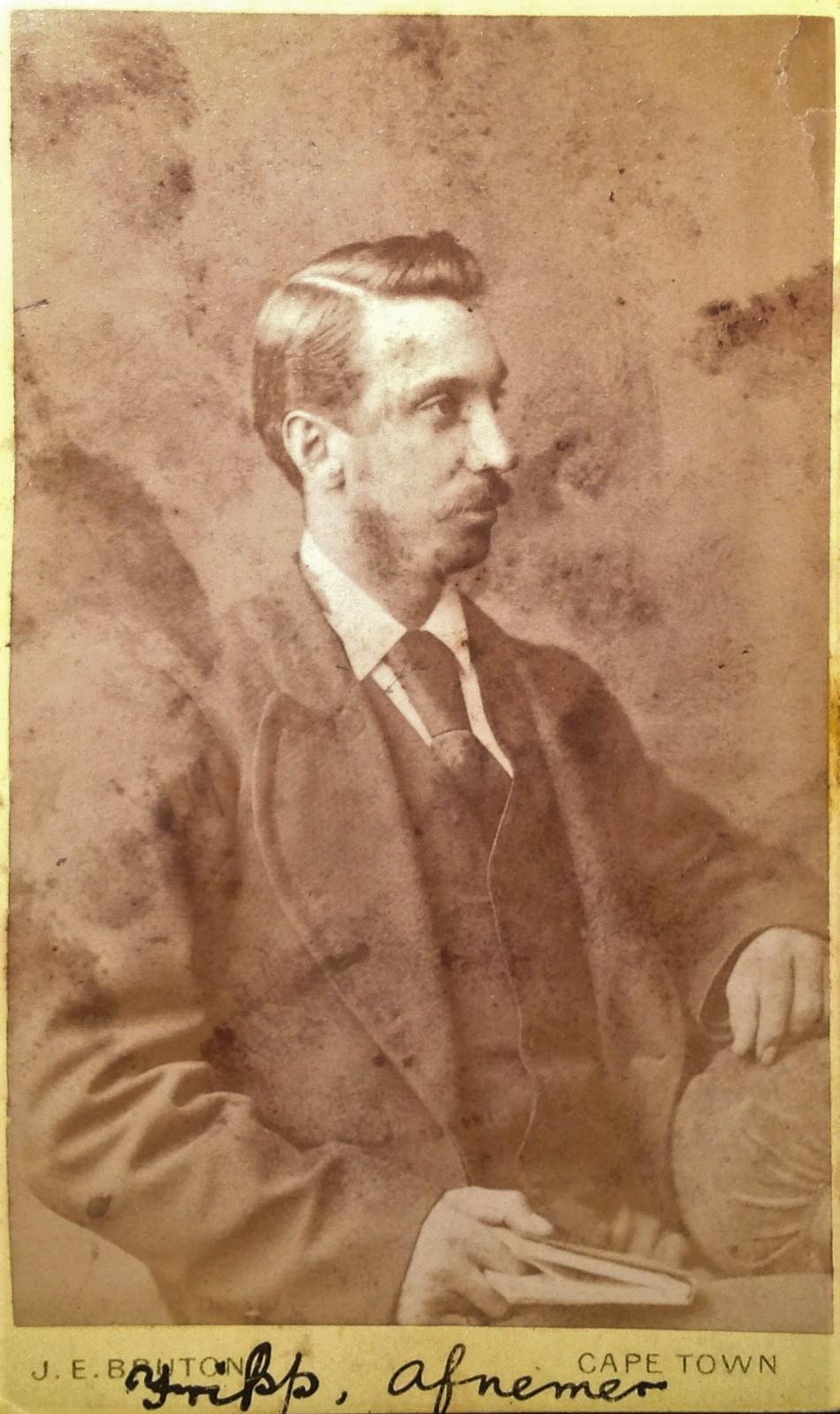

Photograph by James Edward Bruton of fellow photographer Henry Edward Fripp – Based in Cape Town (Adderley street), Beaufort West & Worcester (Circa 1882). Although the inscription suggests that this is a photograph of Fripp, the possibility does exist that Fripp actually captured the image and simply used Bruton’s card stock to paste the image on (highly unlikely)

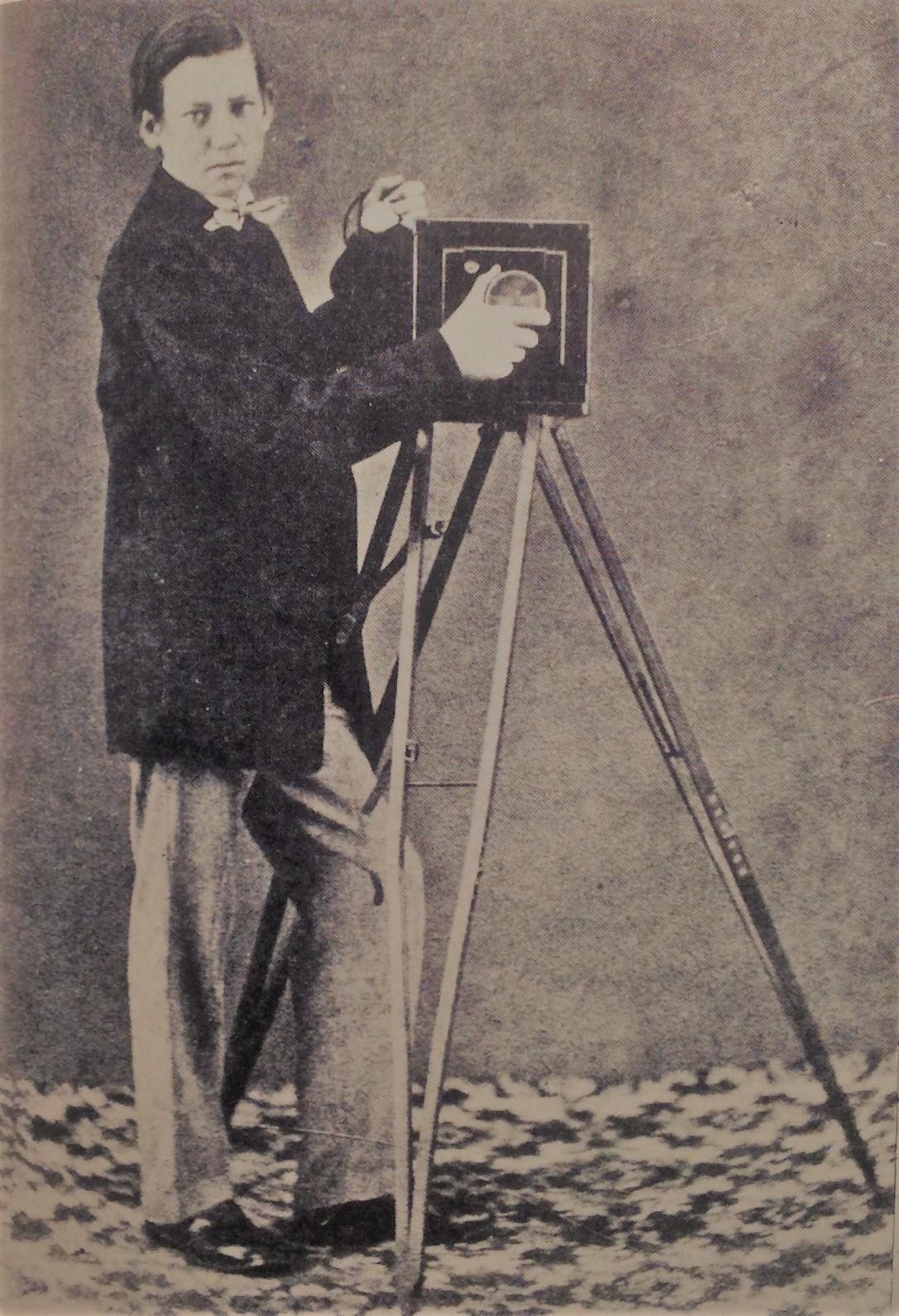

GN Tudhope aged around 15 years old with his first camera. Many young men started as assistants in professional studios before they became professionals themselves. Tudhope later established himself as photographer in King Williamstown (image reproduced from Secure the Shadow).

The focus of the revised directory has been on:

- only recording professional photographers, yet it is acknowledged that amateur photographers may also have been inadvertently been recorded;

- only recording long term based South African based photographers, yet it is acknowledged that visiting/travelling photographers from abroad (shorter than 4 to 6 months) may have also inadvertently have been recorded;

- Identify any studio assistants (including sons of photographers);

- Identify possible linkage between various studios in that well-established photographers are known to have bought out smaller studios or studios from photographers who relocated;

The two biggest gaps in the attached directory lies with Missionary photographers and Governmental photographers.

Missionary photographers contributed significantly to South Africa’s rich photographic heritage. They would not have advertised their services and typically should be excluded from the directory given the fact that they were not professional / commercial photographers.

Government photographers would have been employed by government departments such as agriculture, prison services or railways. The majority of photographers employed by government entities also did not advertise their services in their private capacity resulting in them not being generally known. The author is currently in the process of researching early South African railway photographers.

The personal stories behind each photographer remain fascinating. Some photographers were solid citizens and immensely successful in their chosen career whilst other had checkered careers. One or two turned out to be criminals whilst another two or three developed mental disorders and had to be incarcerated. At least one suicide has been recorded, namely John Paul during January 1862 (not on South African soil).

Some died at a young age, whilst others opted out of the profession entirely to follow alternative careers. One Pretoria based photographer is known to have become a detective for example.

Photography was not a common career for females at the time, resulting in a small percentage of names reflected on the directory being female. Click here to see article previously placed on this topic. The author would be elated if his hypothesis that no Black (African, Coloured or Indian) commercial photographers practiced the art of photography between 1846 and 1915 is proven wrong.

Foreign photographers were initially attracted to South Africa from the mid-19th century onwards due to ethnographic photographic opportunities, diamond and gold finds and various wars. The Anglo-Boer war (1899-1902) brought a flood of journalists and photographers into the country resulting in historical and cultural records providing rich insights into the manners, customs, dress, attitudes or interests of the past.

Although the three main nationalities that would have settled in South Africa as photographers were British, German and Dutch, a variety of other nationalities also practised the art of photography in South Africa, namely Russian, French, American, Swiss etc. Although ongoing research still needs to confirm this hypothesis, South African born photographers for this era seem to have been in the minority.

The following parties have been excluded from the attached directory:

- Early contributors to the field of photography such as:

- Henry Galpin who installed South Africa’s first Camera Obscura at his home (Grahamstown);

- Chemists who were the main distributors of photographic materials at the time;

- Colourists taken in by photographers. One such example is Francis Lewin Dashwood who worked for Arthur Green as a colourist.

- Large number of visiting photographers to South Africa who may have captured multiple images in South Africa, but never resided in the country for an extended period. Some examples include:

- George Washington Wilson whose son toured the country with a professional Scottish photographer around 1900 during which they produced some 800 images under the initials GWW;

- Sir J. Benjamin Stone who took some 400 photographic plates during 1894;

- Rev William Fitz-Harry Curtis (an amateur photographer) who produced The Royal Edinburgh album of Cape Photographs (1869);

- Anglo war correspondents (Zulu war (1879) and Boer war (1899-1902)) – a research topic of its own.

- South African photographers that may have been based in concentration camps (mainly abroad) during the Anglo-Boer war period.

Early Picture postcard image of Victoria street in Dundee showing photographer WL Atwell signage (Just left of electricity pole in front - Circa 1910)

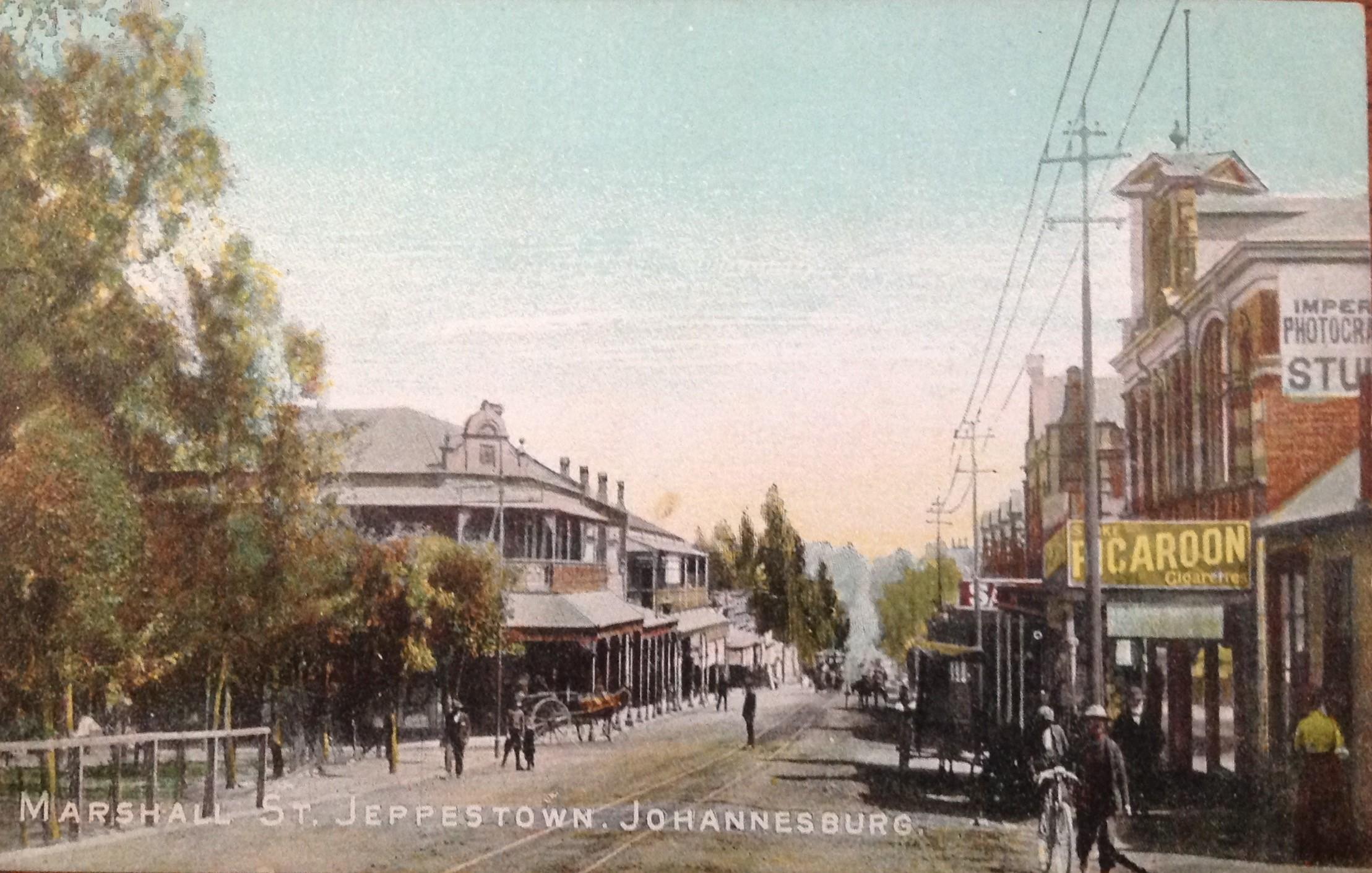

Early Picture postcard image of Johannesburg showing Imperial studio signage on the right in Marshall street (Circa 1912)

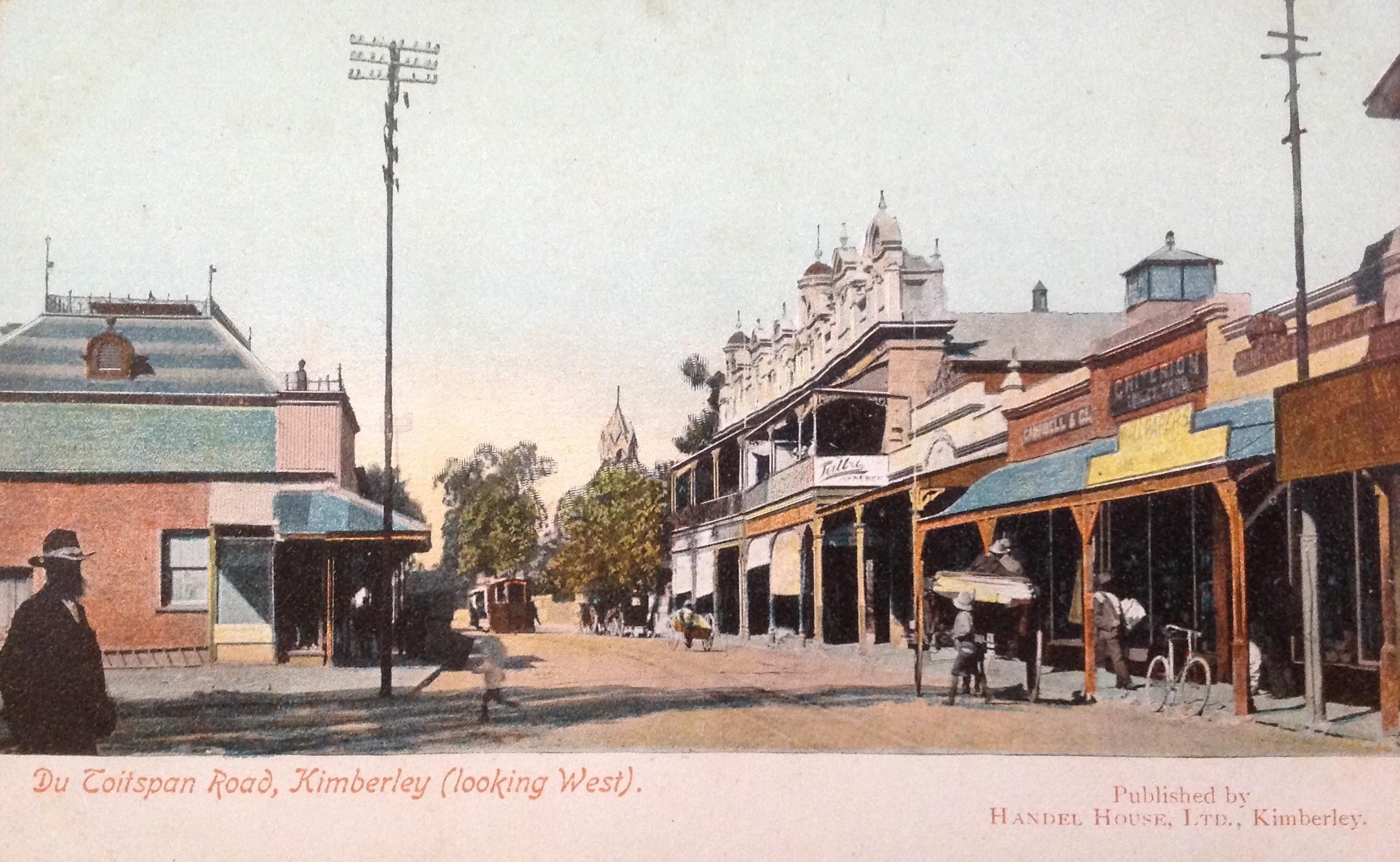

Early Picture postcard image of Du Toitspan Road in Kimberley showing Talba studio signage (white sign in middle of image – Circa 1908)

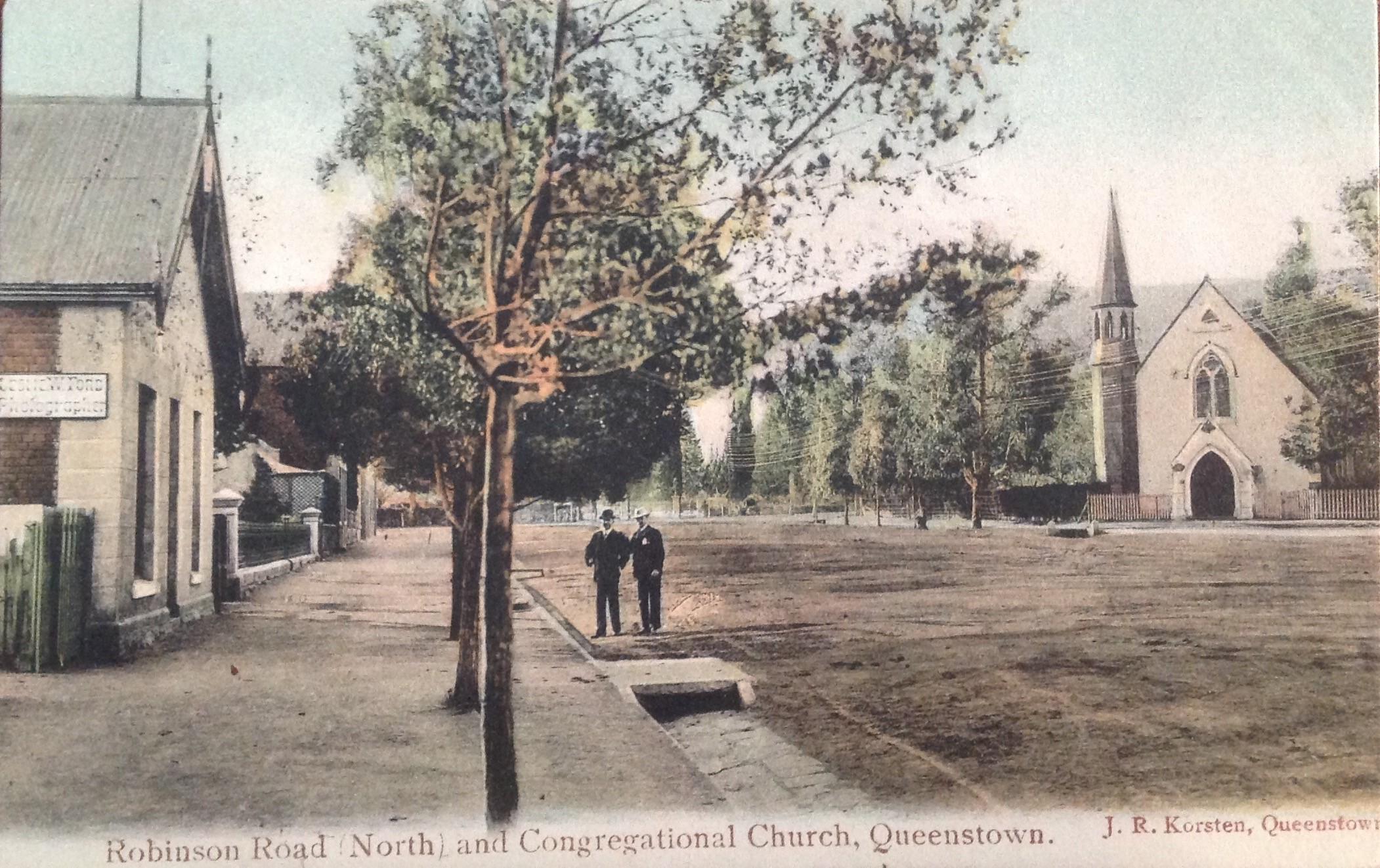

Early Picture postcard image of Queenstown showing Lesley Ford studio in Robertson road (building on left - Circa 1908)

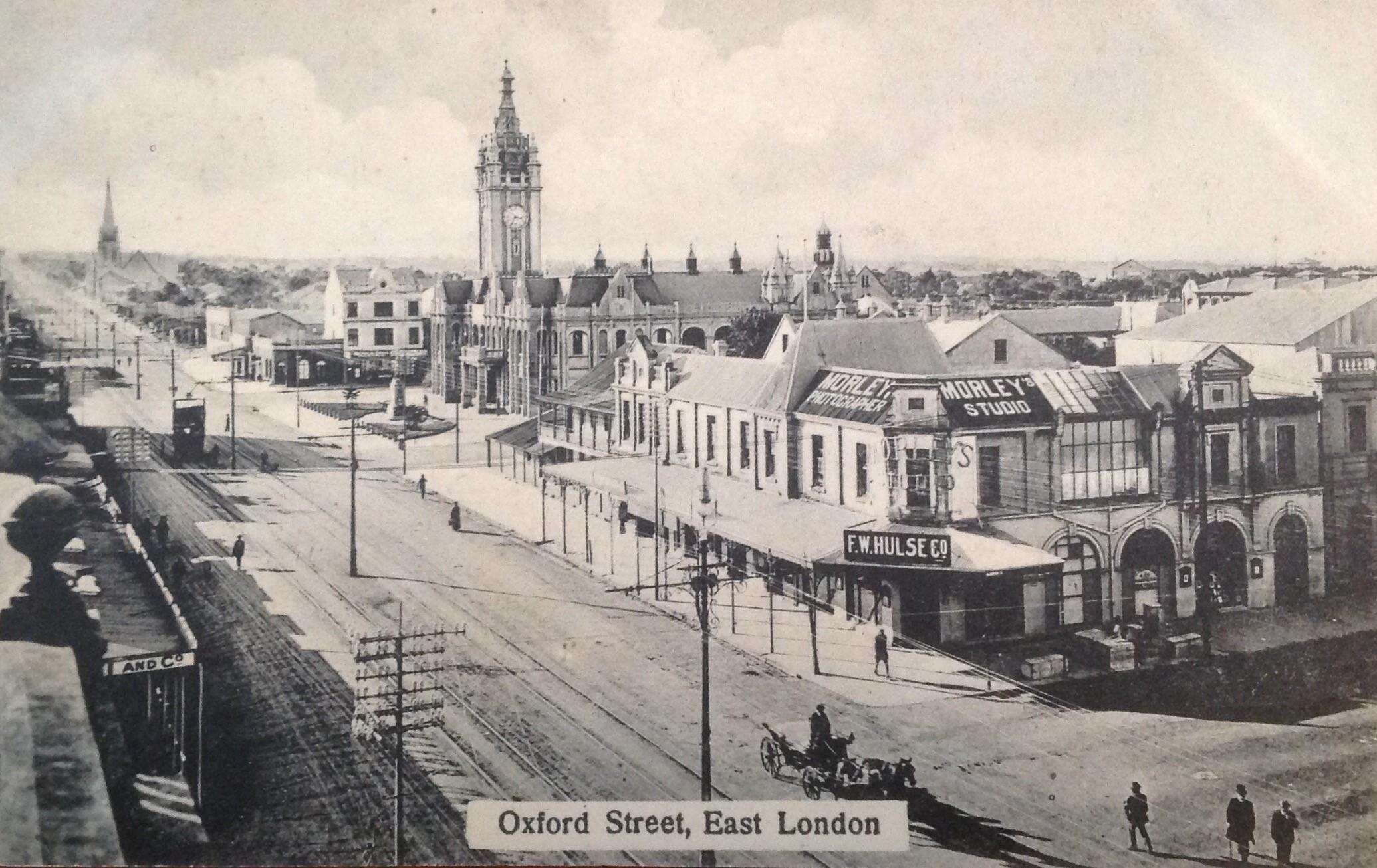

Early Picture postcard image of East London showing the Morley studio in Oxford road (Circa 1906)

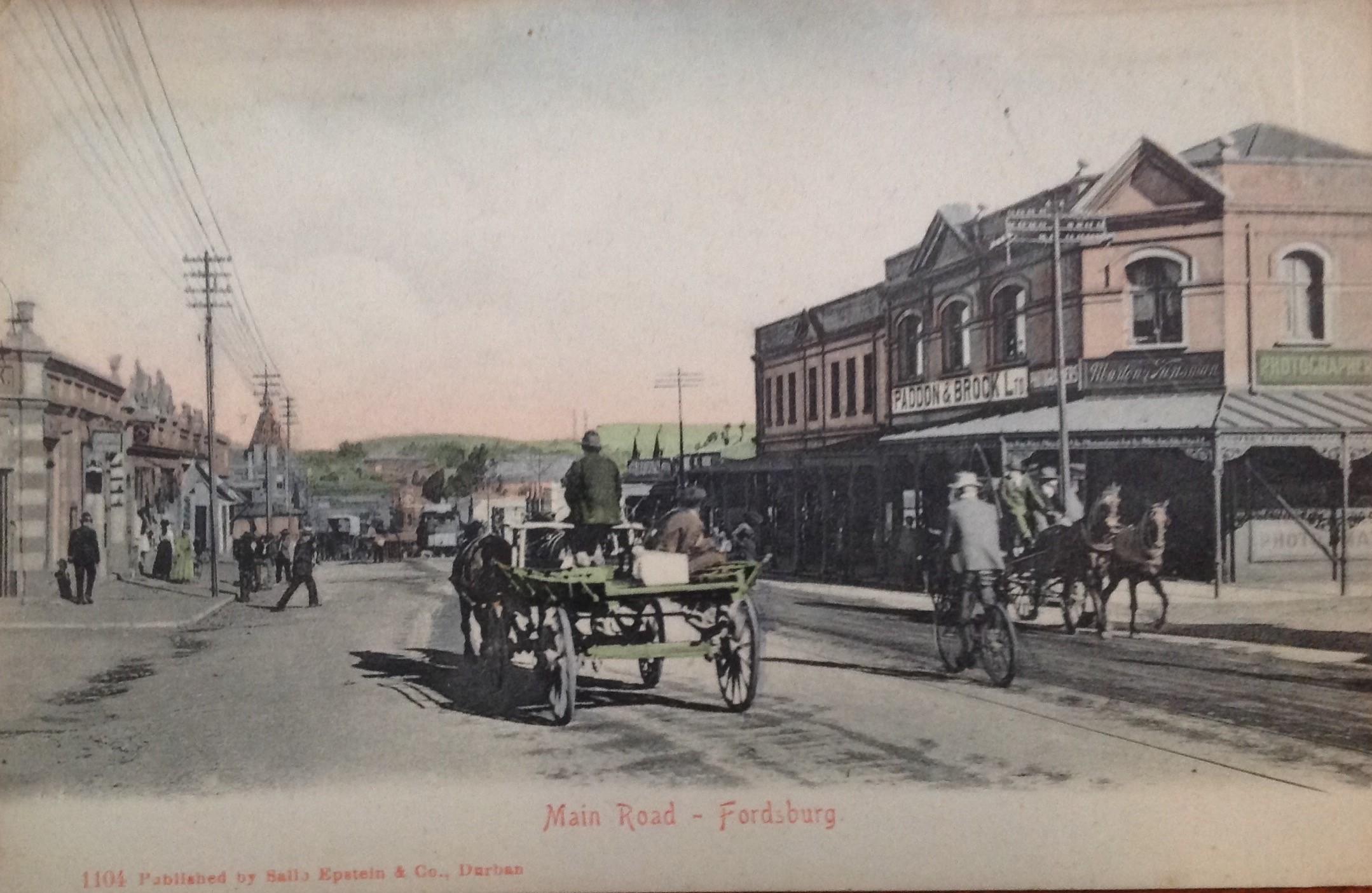

Early Picture postcard image of Johannesburg showing the Murton & Kinsman studio in Fordsburg (Circa 1906)

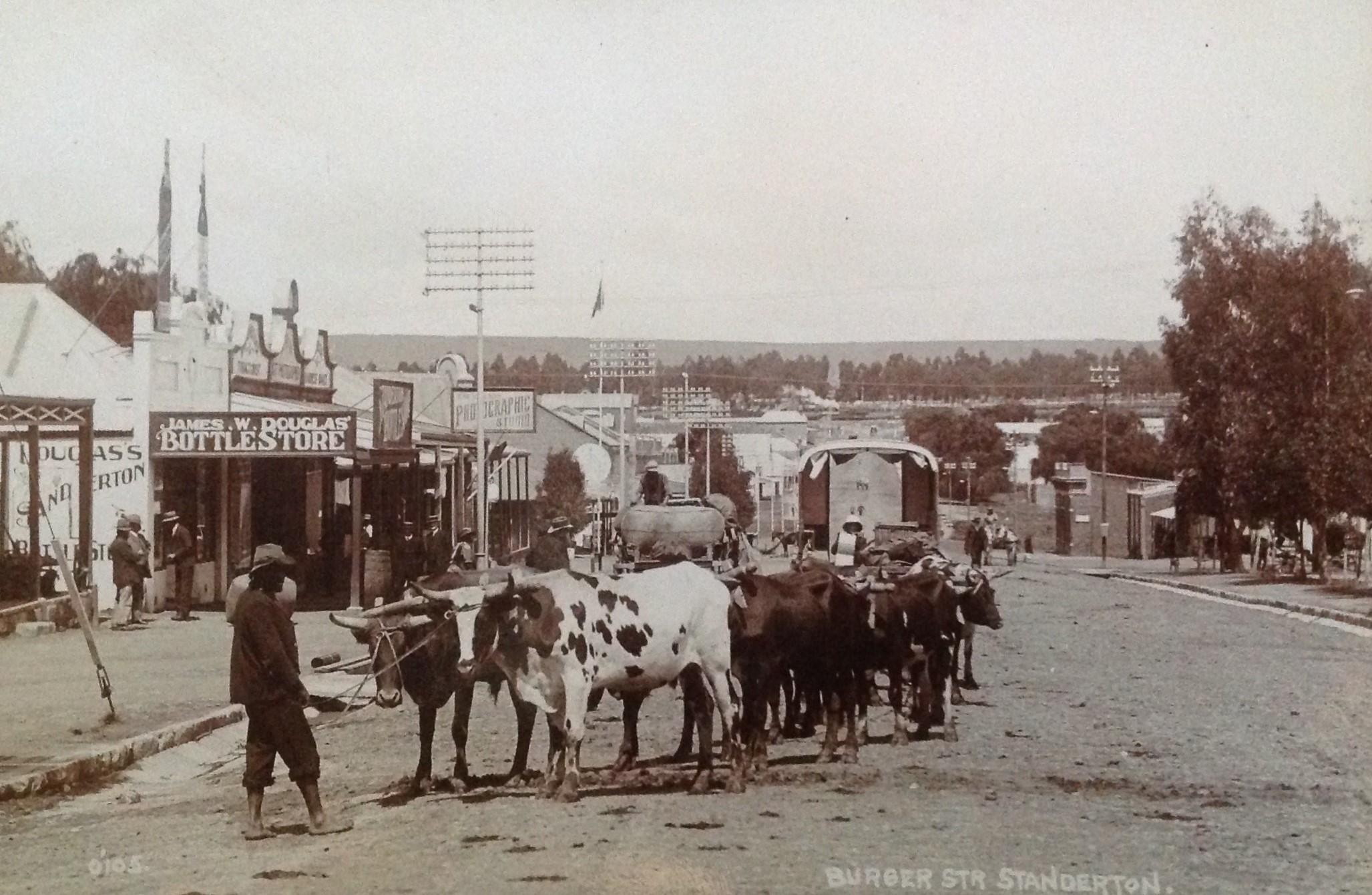

Early Picture postcard image of Burger street in Standerton showing the studio of unknown photographer (Circa 1912)

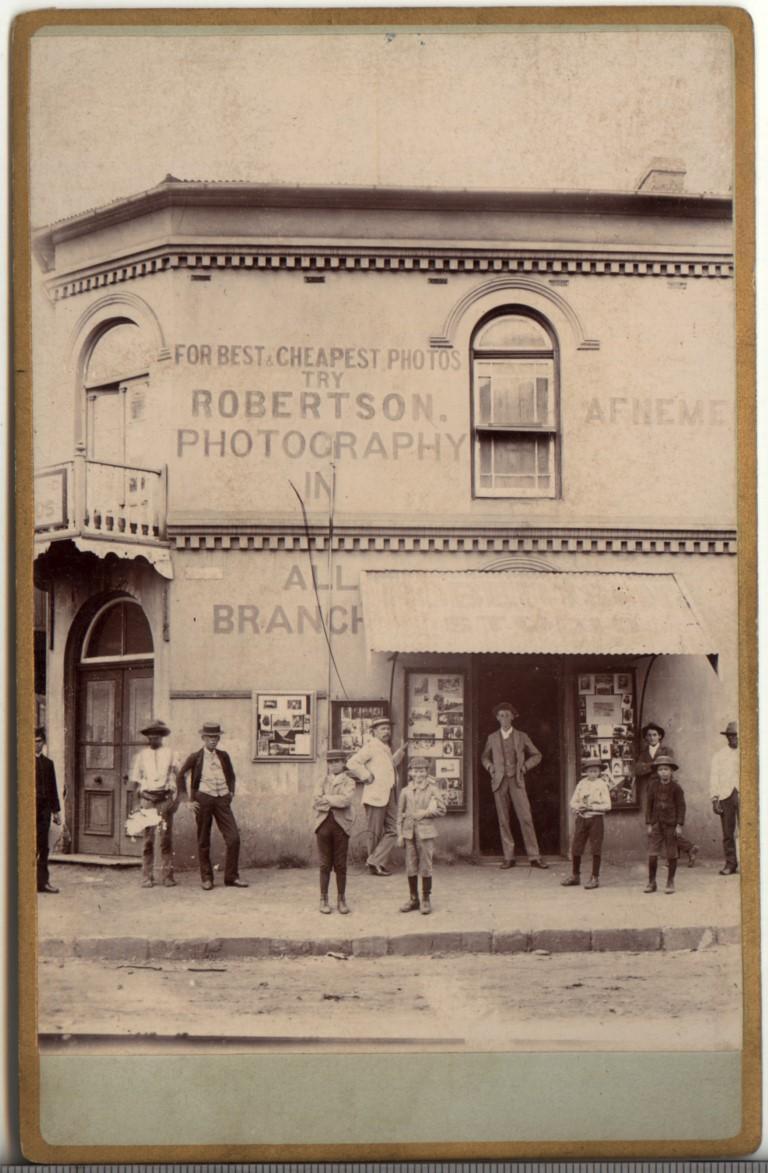

Cabinet card format photograph showing the Robertson studio based on the corner of Church and van der Walt street in Pretoria (Circa 1900)

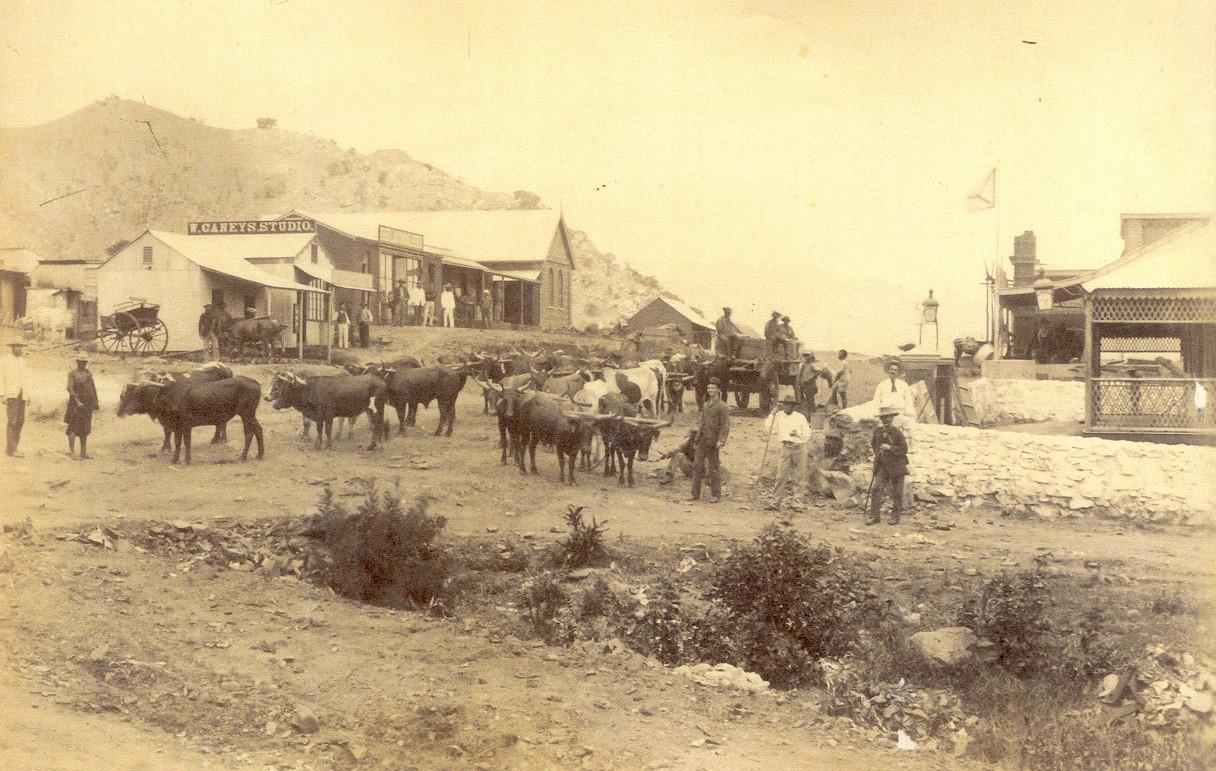

William Harry Caney’s studio in Pilgrims street - Barberton. William was the son to Durban based Benjamin William Caney (image provided by Barberton museum – Circa 1888)

Early Pretoria street scene by photographer HF Gros. Church street looking west. The Swiss photographer Gros’s studio is the white double storey building in the middle of the image (corner van der Walt & Church street - Circa 1880). This is the same building as can be seen on the Robertson studio image included in this article.

5) About the revised directory (click here to download)

The master directory (maintained by the author) also contains additional information on some photographers, such as, where a particular photographer may have completed his apprenticeship, partnerships, studio buy-outs etc. The Safier document also contains valuable information along these lines. In order to keep the attached directory simplistic, any such additional information has been excluded from the directory.

Also:

- In updating this list, only photographers whose photographs have been identified or those confirmed by fellow researchers have been listed. Where doubt exists as to whether an individual acted as photographer, the name was not included on the directory. Some early shipping passenger lists would record a person landing in South Africa as being a photographer, yet no evidence has surfaced to date that they were active as photographers. The possibility remains that such individuals may have been assistants to established photographers. Two such names are German citizens Grob & Marz who arrived in South Africa and had their names recorded as photographers on the ship’s passenger lists;

- Where an alternative spelling of a surname has been identified, this alternative spelling is included in brackets next to what is believed to be the correct spelling of a surname;

- Bensusan did not focus on recording the country of birth of photographers. The current directory started recording the origin of each photographers. Much ongoing research is required to update this particular aspect of the directory;

- Many photographers produced card stock with their name printed on them but did not add the town they were located at. This resulted in the photographer’s town location being recorded as “unknown” on the attached directory;

- Where a photographer was based in more than one town during his career, such name has been recorded for each town he was active in. This therefore results in some duplication of names recorded;

- The directory includes some 67 studio names (under “Studio name/photographer unknown”) where the photographer who was active in that particular studio has not been identified to date. This in itself may result in duplication of names recorded in that the photographer may have been recorded, yet the studio name has not yet been associated with the particular photographer;

- The second last column of the directory with heading “BL” (Bensusan listing) indicates whether the photographer has been identified/listed by Bensusan in his 1963 work;

- The last column of the directory with the heading HPRC (Hardijzer Photographic Research Collection) confirms whether actual photographs of each particular photographer can be found in the said research collection.

For a number of photographers initially recorded by Bensusan, actual photographic evidence has not been found by the author to date. These names were not removed from the directory.

6) Reflection on photographic formats used in researching the attached updated directory

Taking photographs during the early Victorian era was an elaborate and difficult process.

During 1851, photography was barely 12 years old yet for economic and other reasons the Daguerreotype and Calotype (Talbotype) processes in place then did not lend themselves readily to mass production of images for sale to the general public.

The publication of Frederick Scott Archer’s collodion “wet-plate” negative process during 1851 (same year as Daguerre’s death), constituted a marked improvement on all previous photographic methods and had far-reaching repercussions on the photographic and publishing world, particularly as the process was not only practical and more economical but was also free from patent restrictions.

Collodion (Greek word meaning glutinous) has been used in 1847 as means of protecting wounds. A mixture of cellulose nitrate, or guncotton, with alcohol and ether, it congealed to form a tough film when poured onto a surface. Scott found that by dipping the plates into silver nitrate and exposing them while wet, he could develop the negative image and strip it off the glass on a film of collodion. The entire process of coating plates, exposure in the camera, fixing and developing had however to be completed before the emulsion dried. This wet collodion method tied the photographer to his dark room, whether in a studio or out in the field in a portable darkroom.

The compilation of the attached photographer directory relied mainly on obtaining original Carte-de-Visite, Cabinet Card or larger format paper-based formats. Original Daguerreotypes, Ambrotypes, glass negatives and stereoviews assisted to a lesser extend in expanding the directory.

7.1) Daguerreotype

The earliest photograph process to be introduced commercially was the Daguerreotype, where the image was produced on a copper plate with a highly polished, mirror-like silver surface. These photographic formats are nearly always protected by glass in a frame, more often found in a miniature case in the form of a little book, sometimes in ornate wooden cases covered with either imitation or real leather. Daguerreotype format photographs are unique objects in that the image could not be reproduced from a negative.

Most surviving Daguerreotypes show silver tarnish which can be restored by experienced restorers. Whilst these images are not particularly rare, South African produced versions are scarce. They are sadly of limited value for South African photographic research in that very few bear any identification of the photographer or the sitter.

Most of these images have survived in the hands of collectors or museums. Considering that these images are more than 170 years old, those that may still surface from family collections may not always be in the best condition.

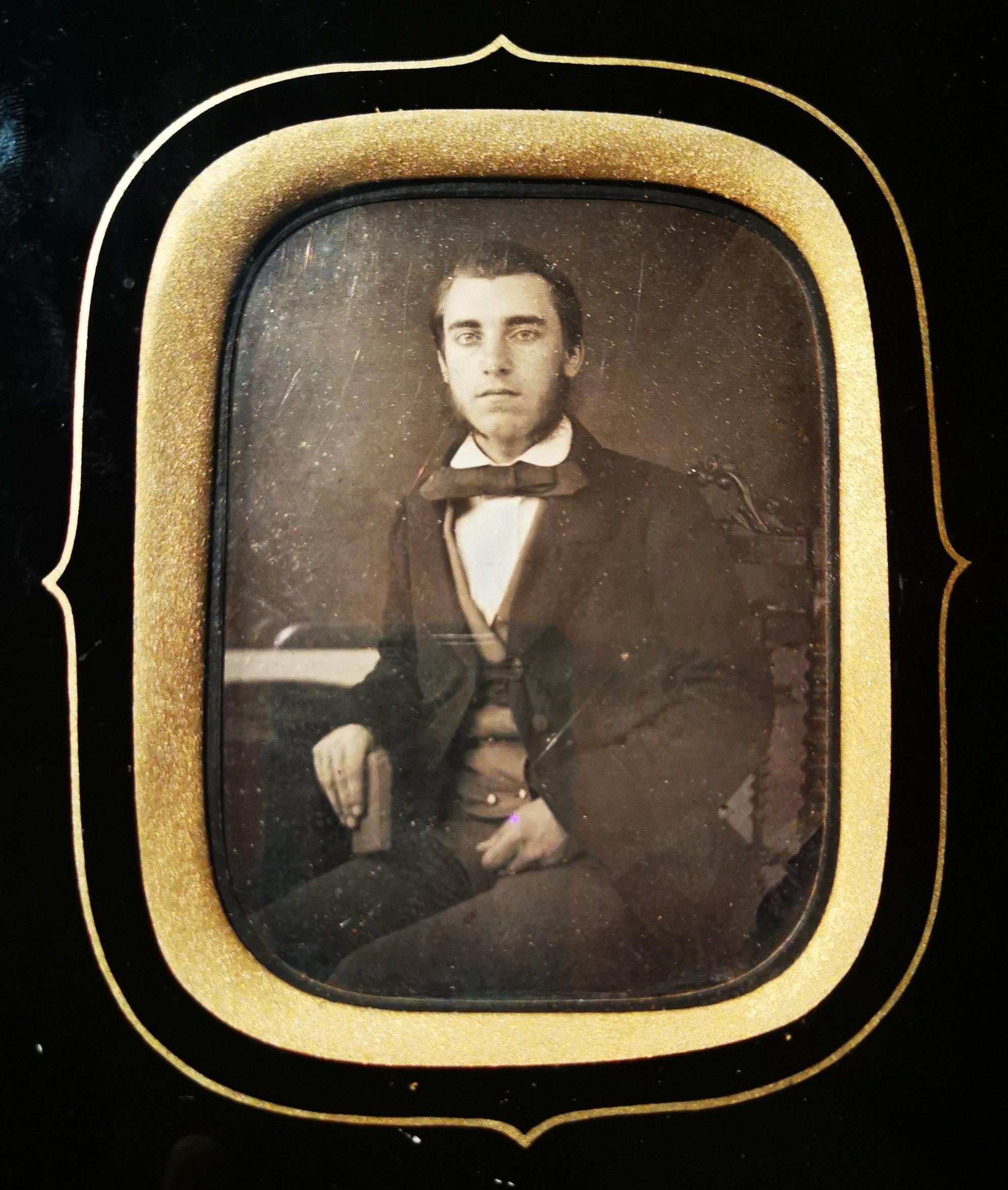

Daguerreotype of South African citizen Hennie Wicht captured in Geneva (Bally – Rue du Perron). The inscription on the back of the image states that Wicht travelled to Europe with his grandfather Servaas de Kock during 1857

7.2) Ambrotype

Ambrotype (1854 to 1865), or a Wet-Collodion Positive (also referred to as the poor man’s Daguerreotype), similar in appearance to the Daguerreotype, is actually a negative on glass. The dark opaque areas, that is those that will appear positive on a print, were bleached to become white opaque areas, whilst the shadows, or transparent parts of the negative were left unchanged. Once the image is mounted on dark background, such as a piece of velvet or a black varnish, the image appears as positive.

As for the Daguerreotype, Ambrotypes are also of limited value in South African photographic research in that very few bear any photographer of sitter identification.

The Ambrotype did not have the troublesome surface reflections of the Daguerreotype and was easier to tint faster and were cheaper to make and easier to sell. Although easy to differentiate between the two formats (requires a trained eye), some dealers still intentionally (or unintentionally) advertise the younger Ambrotype as a Daguerreotype with the hope of generating a higher price.

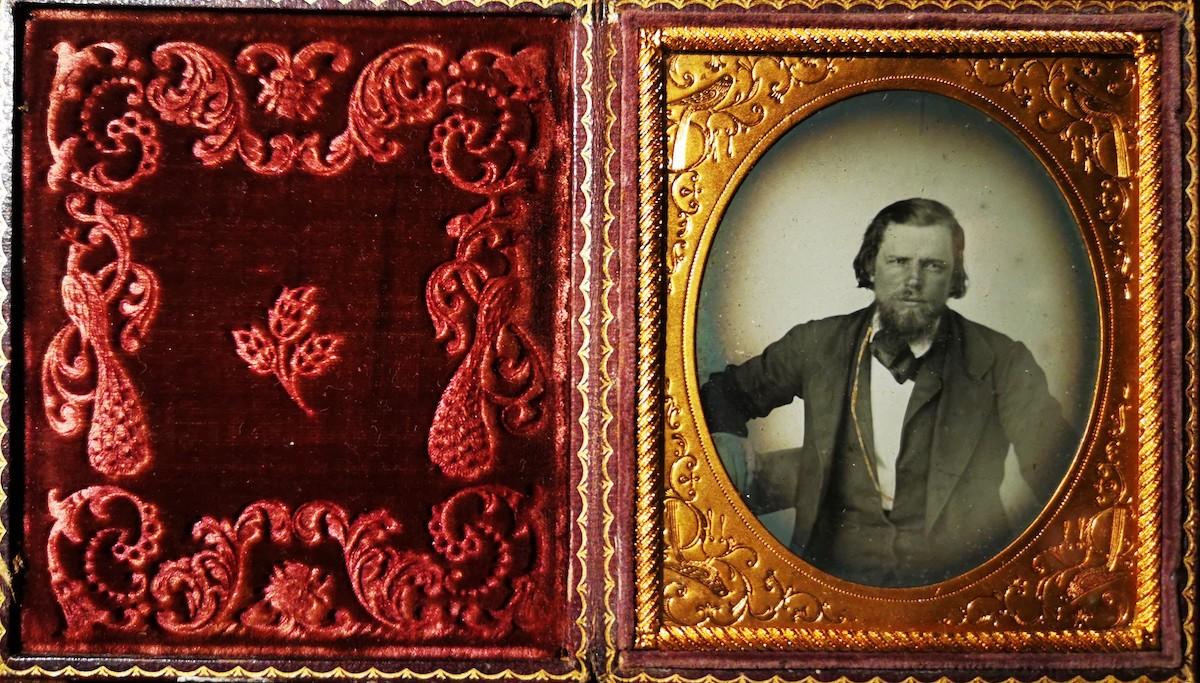

Ambrotype in original case of South African citizen Johannes Jacobus Mostert (born 1834). This image was in all probability taken by a South African photographer (circa 1860)

7.3) Ferrotype

Ferrotypes (or tintypes) are photographs on metal. These images were produced in large quantity all over the world, including South Africa. The tintype was also a unique image and could only be reproduced by re-photographing the image. As for the Daguerreotype and Ambrotype, these images have barely assisted the research in active South African photographers in that very few of these had the name of the photographer included.

7.4) Stereoviews

A stereoview (or stereograph) is a pair of photographic images pasted on a single cardboard mount and when placed in a specially designed stereo viewer provides a three-dimensional image.

The only South African based photographers identified to date to have extensively produced this format were the deep level mining photographers Wilbur Read and the Neilson Brothers.

7.5) Carte-de-Visite & Cabinet Cards

The compilation of the attached directory relied mainly on obtaining original images in these two albumen photographic formats (1850s to 1890s).

During 1859, André Disdéri launched the highly fashionable Carte-de-Visite paper version, with the portrait image affixed to a cardboard mount. This format became the most popular size of professional studio photograph from 1861 onwards resulting in it also being easier to identify the actual photographers in that in the majority of instances the photographer would have applied their names on the pre-printed card stock on which photographs were then pasted.

The introduction of the “carte” also marked the beginning of one of the most important periods of South African photography. Some six years after its introduction, the Cabinet size photograph made its first appearance in the Cape.

Both formats, in their time, were the most fashionable photographic format sizes for the recording of people, scenes and events. Bull & Denfield (1970) suggested that well over 90% of the photographs taken in the period prior to 1900 were in these two formats.

Beautiful design on back of Cabinet Card format photograph: Standerton based Julius Hesselson. Amongst other he states that Flash Light Photography is a speciality.

Beautiful design on back of Cabinet Card format photograph: Heildelberg & Standerton based photographer RCE Nissen. He was also based in Pretoria for a number of years. Note the angel sitting on the camera

Beautiful design on back of Cabinet Card format photograph: Kimberley photographer C Evans based at 53 Du Toits Pan Road. Evans ordered these pre-printed stock cards from the printing firm Marion in Paris. It is additional snippets of information such as the studio addresses on the back of these cards that assists research

Beautifully designed back of Cabinet Card format photograph: Cape Town based photographers Ashley & Rutter (Tramway studio). The studio ordered these pre-printed cards from C.E. & C (probably a British based printing firm). It is additional snippets of information such as the studio addresses on the back of these cards that assists research.

Beautifully designed back of Cabinet Card format photograph: Cradock based Passmore & Nevay photographers. The studio ordered these pre-printed cards from the printing firm Marion in Paris

Artistic design on back of Carte-de-Viste format photograph: Cape Town based photographers Gordon & Smith (The Art Studio). The studio ordered these pre-printed cards from C.E. & C (probably a British based printing firm). It is additional snippets of information such as the studio addresses on the back of these cards that assists research. Note the camera the seated lady is leaning on.

8) Closing

It is to the South African based photographers listed in the attached directory (plus those inadvertently left out) that we are indebted for the rich visual history left behind.

Much ongoing research is still required on the history of South African photographic history. The spectrum for such research remains near endless – with vast opportunities for post graduate work.

Any additional information on the attached directory will be appreciated. Every little snippet would be of value, such as full names of the photographer or country of birth. The author can be emailed on carol.hardijzer@webmail.co.za should a reader be able to provide any such snippets.

The author intends updating the 2020 version of this directory with 5-year intervals (Deo Volente). He always welcomes any original photographs for addition to this research collection.

Special Acknowledgement: Australian based photographic historian Dr. Marcel Safier who freely provided his research collated on South African based photographers.

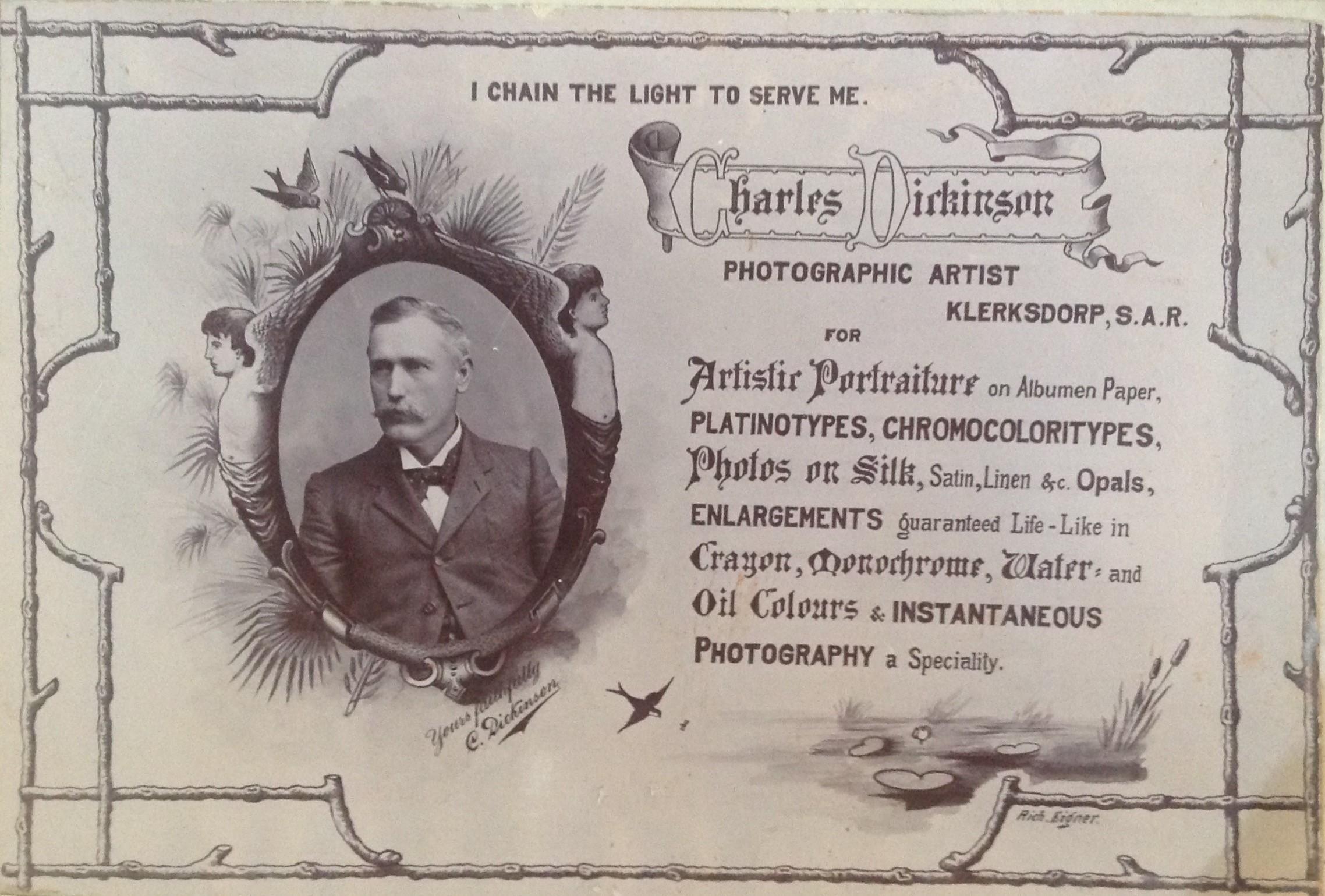

Main image: Unusual advertising card in Cabinet Card format of Klerksdorp based photographer Charles Dickinson. The card was designed by Richard Eigner. Note the spelling mistake of the surname on the card – Dirkinson instead of Dickinson. It was not uncommon to find spelling errors such as these on advertising or pre-printed stock cards. Note the variety of services provided by Dickinson.

About the author: Carol is passionate about South African Photographica – anything and everything to do with the history of photography. He not only collects anything relating to photography, but also extensively conducts research in this field. He has published a variety of articles on this topic and assisted a publisher and fellow researchers in the field. Of particular interest to Carol are historical South African photographs. He is conducting research on South African based photographers from before 1910. Carol has one of the largest private photographic collections in South Africa.

Sources:

- Ancestors.co.za (Photographers of the 19th century in South Africa)

- Baldwin, G. (1991). Looking at Photographs – A guide to technical terms. London. Paul Getty Museum

- Barrie, S. (2002). Australians behind the camera. Directory of early Australian photographers 1841 to 1945. Sydney South. S. Barrie

- Bensusan, A.D. (1963). 19th Century Photographers in South Africa. Africana Notes and News. 15(6), 219-252

- Bensusan, A.D. (1970). Silver Images. History of Photography in Africa. Howard Timmins. Cape Town

- Bull, M. & Denfield, J. (Unknown). William Syme – Photographer and Artist. Africana Notes and News (Unknown)

- Bull, M. & Denfield, J. (1970). Secure the Shadow – The story of Cape Photography from its beginnings to the end of 1870. Terence McNally. Cape Town

- Cosen, R. (No date). Victorian photographers (www.cartedevisite.uk)

- Cowan, N. (Unknown). A note on Daguerreotype photographs in South Africa. Africana Notes and News (Unknown)

- Cowan, N. (Unknown). Photographic processes of the 19th and early 20th centuries: Their recognition and identification. Africana Notes and News (Unknown).

- De Beer, M & Barker, B.J. (1992). A vision of the past – South Africa in photographs (1843 – 1910). Struik. Cape Town

- Dietrich, K. & Bank, A. (2008). An Eloquent Picture Gallery – The South African portrait photographs of Gustav Theodor Fritsch, 1863 – 1865. Jacana Media. Auckland Park

- Hardijzer Photographic Research Collection

- Langham-Carter, R.R. (1991). The Early British families of Paarl (www.eggsa.org)

- Malherbe, J.F. (2014). Die rol van neëntiend-eeuse fotografie in eietydse bewaring: William Roe en Graaff-Reinet. Universiteit Stellenbosch

- Munro, K. (2017). TD Ravenscroft and his photography. (www.theheritageportal.co.za)

- Rizzo, L. (2019). Photography and History in Colonial Southern Africa – Shades of Empire. Wits University Press. Johannesburg

- Safier, M. (No date). Australian researcher, Dr. Marcel Safier’s, unpublished catalogue of South African 19th century photographers

- Schoeman, K. (1996). The face of the Country – a South African family album 1860 – 1910. Human & Rousseau. Cape Town

- Stevenson, M. & Graham-Stewart, M. (2001). Surviving the Lens. Photographic studies of South and East African people, 1870 – 1920. Fernwood Press. Vlaeberg

- Unknown (extracted on 25 July 2020). Gribble. (www.drakensteinheemkring.co.za)

- Warner, B. (1983). Charles Piazza Smyth, Astronomer-Artist: His Cape Years, 1835-45. Balkema. Cape Town

- Warner, B. (Unknown). Capturing the image: South Africa’s first photographer. Unknown magazine article.

- Warner, B. (Unknown). Charles Piazzi Smyth Pioneer Cape Photographer. Africana Notes and News (Unknown)

- Warner, B. (Unknown). Charles Piazzi Smyth Pioneer Cape Photographer – An addendum. Africana Notes and News (Unknown)

- Warner, B. (Unknown). Charles Piazzi Smyth Pioneer Cape Photographer – A further addendum. Africana Notes and News (Unknown)

- Wikipedia.org (Charles Piazzi Smyth)

- Wikipedia.org (Photography in South Africa)

- Wikipedia.org (Hugh Exton)

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.