Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

Mel Baker was a crew member of the HMS Gloucester which sank near Crete in 1941. He was one of only a handful of survivors picked up by the Germans. Below is Part 1 of his powerful account of being a Prisoner of War for most of World War II. He was 21 when he was taken prisoner and returned to Port Elizabeth in 1945 aged 25. Click here to download the full account including footnotes and a bibliography. The men in the photograph above from left to right are: Freddie Webster, Andy Andreason, George Bennet, Lofty Shepherd, Len and Mel Baker

On 22nd May 1941 HMS Gloucester was under constant air attack in the Mediterranean near Crete. The day started with the ship having only 18 percent of its main 4” ack-ack ammunition. “G” finally ran out of ammunition early in the afternoon and resorted to firing star shells and practice shells as a final show of fight back. At approximately 3.00 p.m. the inevitable happened. Several bombs, mainly from Stukas, hit “G” and she slowly turned turtle and sank. Fred Webster’s watch stopped at 3.35 p.m. in the water.

The HMS Gloucester from a postcard which Mel Baker sent home to South Africa prior to 1941

I was at my action station in the shell gallery at the time. We felt all the thumps of the bombs hitting the ship. No communication came through to us to abandon ship, but it was obvious to us that we were in serious trouble. Eventually a voice from the turret above us said, “Come up top.” So we left the shell gallery and made our way to the well deck to find that the ship had listed to port and the water was almost level with this deck. By then there were hundreds of men in the water, so all that was needed was to remove shoes, inflate lifebelt and step into the water. In the water I saw several South Africans. I looked around for some means of support in the water and decided to get near a Carley float and stick around. Being in a group I’d have a far better chance of rescue. Many of the men in the water gave up within a very short time. I couldn’t believe that they would give up so quickly. A leading seaman said to me, “Bakes, let’s swim for it.” I replied, “Tommy, do you think you can swim the Channel?” Next day he thanked me and said, “Thank goodness I took your advice.”

All the lifeboats were shattered by the bombs so we had no means of getting to land, which was visible from where we were. All that was left were a few Carley floats. The cruiser that was with us, HMS Fiji, dropped some of her Carley floats near us. Not nearly enough to accommodate the hundreds of men in the water, with the result that about 60 men were trying to climb on to the float which was meant to accommodate about 20 and with another 30 hanging on the ropes on the side with the result that it kept on capsizing – what a shambles. In this struggle for survival a couple of boys kept pulling me under to support themselves. The only solution was to swim away from the float and wait until it settled down, then swim back and hang on to the side. When it started tipping again I swam away and came back each time. Eventually the number of men left by evening was down to about 15 so we were all able to climb on to the damaged raft and sit on the sides. During the night several gave up and drowned leaving only nine of us the next morning to be picked up. I had the Chief Cook sitting next to me. He kept on saying, “I’ve had enough.” I kept on talking to him and assured him that the destroyers would come to pick us up. Of course, they never came. Also on the raft was the Captain of Marines, who had a nasty wound at the back of his head and neck. After a while, he started floundering in the middle of the raft which was submerged. I tried to help him and heard a splash behind me. It was the Chief Cook who just leaned backwards and was gone. Shortly after that the Captain of the Marines passed away. We just had to put him into the water.

We spent the night waiting for the Royal Navy (RN) destroyers to come and pick us up, but nothing came. It was a very long night. During the night we drifted away from the other rafts and there was no sight of them in the morning and so we lost the advantage of keeping together. We were the last to be rescued.

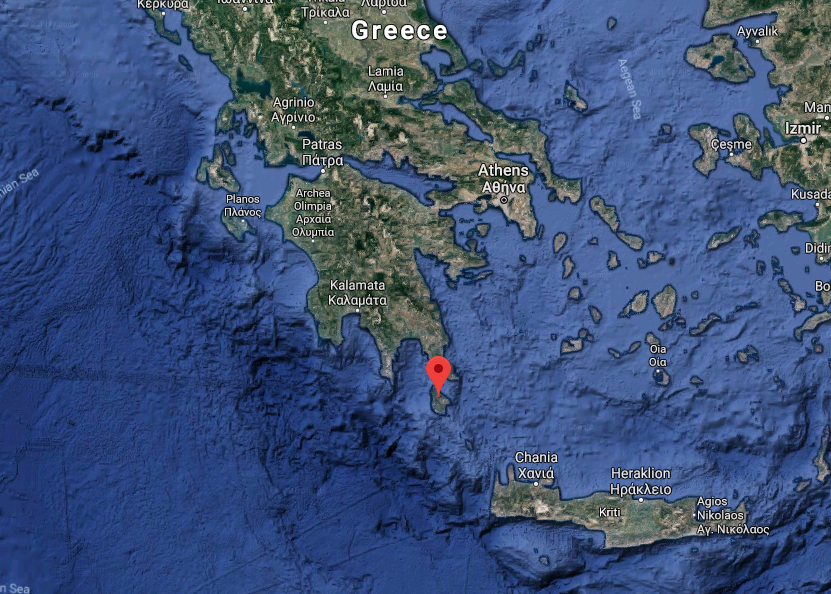

In the morning we could still see land but it was too far away to even think about swimming to it and we had no means of paddling our float to land. It was just a matter of staying calm and hoping that someone would come to our rescue. Nothing was happening until eventually a German aircraft flew towards us and I thought, please, no more machine-gunning and bombing, as they had done the previous day when we were in the water. Much to our relief, the aircraft dropped flares over us and sometime later a small ship arrived manned by German sailors who rescued us and took us to the island of Kythera. Of course the first words we heard from the Germans were, “For you the war is over.” That was our first day as POWs. Of all the possibilities of what could happen to me during the war, one I never thought of was being a POW.

The following was written by Mel at the back of this photograph: HMS Gloucester. Just before being sunk 22nd May 1941. North West of Crete. 75 survivors picked up the next day and landed by Germans on Kithira (sic). Further 10 survivors accounted for in Greece. This photo given to POW by German and passed on to me.

When I left the Gloucester I was only wearing a singlet and trousers. On the rescue ship we were stripped and our clothes put on the deck. I kept my money belt and life jacket. We were put into the hold where there were already other Gloucester survivors who had claimed the bunks and blankets so we were left sitting on the deck of the hold. I was given water and a piece of bread which I didn’t manage to hold down. We landed starkers. Next day I was looking for my clothes – found my trousers on a marine but soon had them off him, but my singlet I never found. Unfortunately, my trousers had a big hole in the bottom due to the rubbing of the rope on the float.

We were landed at Kapsali Bay where we were imprisoned in a house right on the sea front. We were the last to get there and found that the total survivors numbered 75. (Later we found ten more in Greece.)

On Kythira there was no provision for POWs, and the Germans said they could not feed us and were not prepared to share their own meagre rations. Thank goodness for a 15 year-old boy called Nicos who saw our plight, and with the help of two of his friends scouted the island to bring some food to us. At first the Germans would not allow him to give it to us, but his friends – one of whom could speak a little German – spoke to the guards in the front while Nicos smuggled the food through the back fence. After a couple of days the Germans relented and allowed Nicos to bring food and clothing to us. From the clothing brought to us I acquired a pair of trousers which I think must have been from a cavalry man as they were rather broad on top and narrowed to just over the knee. Later, I also acquired a French army shirt. This clothing was all I had for some months.

Location of Kythira / Cythera (Google Maps)

The first survivors to arrive on Kythira were marched naked from the landing point along the sea front to the house, which had previously been occupied by German soldiers. Among the German troops who were in Kythira were survivors of the sea invasion convoys that had been decimated when on the way to invade Crete. None of them reached their objective. The Royal Navy, mainly destroyers, sank a lot of them and those that were not sunk turned back to the mainland of Greece.

In the town above Kapsali were 120 German paratroopers who were all that remained from the battalion of 1500 originally sent over. The reaction to British sailors who had been responsible for the destruction of their convoy was to shoot them all. The first of our survivors to arrive were lined up and stood against a high wall and told that they would be shot. The German medical doctor intervened and quoted the Geneva Convention. A naval officer said, ‘These are our prisoners, not yours.” After this, the guns were lowered. I only arrived on the island after this was all over, so did not have to go through such a traumatic experience. For once, last was the best.

Life on Kythera (we were there for ten days) was best forgotten as there was nothing to do, very little to eat, no reading matter, no cards, just the same boring routine. The only good thing was we were occasionally allowed to go for a swim, and there was a fresh-water tank near the sea front where I managed to have an occasional wash. One German guard even lent me his soap on one occasion.

Greece and Yugoslavia

After ten days on Kythera we left for the mainland of Greece. We were put in the hold of a caique which had been carrying manure by the smell of it. I didn’t fancy sitting nor sleeping on this deck, so climbed onto the cross beam (about a foot wide) which had two flanges against the boat’s side, so I was able to lie on my stomach and rest my arms along the flanges alongside my head and sleep.

The journey took two days as the sea was rough and we anchored in the bay of some small island for the night. Next day we were allowed on deck, which was a relief from the smelly hold.

We landed in Piraeus and were marched barefooted and very scruffy through the streets and filmed for German propaganda. The Greeks lining the streets tried to throw cigarettes to us – one old lady got too close and the next moment she was on the ground thanks to a German rifle butt knocking her flying.

We marched to a camp where a register was made of our details such as date of birth. One lad of 16 was jeered at by the Germans for the British having such a young boy fighting for them. (Later the German army was full of 16 year-olds).

The day after landing in Piraeus we were taken by lorry to Corinth, where a POW camp was set up. The conditions here were terrible – no hygiene, toilets were holes in the ground, no wash houses, food almost non-existent. The tea we were given tasted and looked like Condy’s crystals (Potassium permanganate, KMnO4). A loaf of bread was shared among ten men, ersatz coffee (acorns), watery cabbage soup. That was it for a day. There I acquired a French army shirt.

We were marched from Corinth camp to the railway station and taken to Athens by train. Here we were herded into cattle trucks – about 50 per truck – no place to lie down and not enough space for all to sit at the same time with any degree of comfort. Our destination – Salonika.

On the way north we had to leave the train as retreating Allied troops had blown the tunnel under the mountain. A German officer took pity on the “G” lads, who naturally had no boots, and took us over the mountain on a lorry. This was the first real march I missed; there were others later on in my POW career. One of the reasons I joined the navy was that I disliked marching and the navy offered me the opportunity to avoid long, arduous marches. On the other side of the mountain we once again entrained and finally arrived in Salonika not in good shape as en route the rations were even worse than those in the camp.

The camp at Salonika was the most disgusting place, worse than all the others put together: just large rooms with bare boards and nothing else. The food was the usual - coffee for breakfast, tea which had a peculiar pink colour – we thought it might be permanganate – lunch the lousiest of all so-called soups, evening 1/5 loaf of black bread.

Sleeping on the floor was quite an experience – we used to joke that you never woke up in the same place as the bed bugs had carried you away. All the other unpleasant friends such as lice, fleas, flies, etc were present. Hygiene was very primitive – nobody by now had any soap – not that I had any of my own. Toilets were very primitive – just an open half pipe running the length of the toilet with water running along it to wash the sewerage away. So many men had dysentery, etc, etc, so not a nice place to visit.

The camp commander was a real sadist. He enjoyed making our lives as miserable as possible. Parade at 6.00 a.m, left standing for hours on end. Anyone who did not please him felt the end of a rifle butt. Fortunately my stay in Salonika was too short for me to be out on a working party – hard labour on the meagre rations. After about ten days in Salonika we were moved out to be taken to Marburg in Yugoslavia where a proper POW camp was established. Little did we know what sort of hell the journey was to become.

We were herded once again into cattle trucks – 50 per truck. I was one of the last on the truck – just my luck – as the first guys had got themselves sitting down against the sides of the truck and had a back rest. The guys in the middle could barely sit down in a huddle. To make our plight worse, the truck behind us (mainly Aussie) had bashed a hole through, but were caught escaping, and were distributed among the other trucks – we got seven of them, which made 57 in our truck.

No water or bucket for sanitation was provided. We sailors had to rely on the army chaps to share their canisters of water with us. When the train stopped dozens of water bottles were thrust through the ventilation slits with appeals to local civilians to fill them. Often the nearest water was some distance away and the obliging civvies could not get back to the train before it pulled away again. When the train stopped the doors were opened but no-one was allowed to get out, so bare bottoms were stuck out so the guys with dysentery could relieve themselves. Weeing was no problem.

Our rations for the trip, given to us on departure, were one fist-sized loaf of bread, three hard, dry biscuits and a small tin of bully-like “meat”.

How we managed to keep ourselves from too much despair I don’t know. One of the Aussies traded his gold watch with a civilian who was next to the train (not the door side) for a loaf of bread. Some of the guys ate all their rations in one day, having been told they were for three days, but in fact they were for four days.

Marburg

At last we arrived at Marburg station, marched to the camp. Conditions were considerably better than any we had had to endure previously, but still not great.

As usual, we were lined up and counted – left standing for ages and then taken for registration, etc.

We were stripped of our clothing which was put through a delousing process, which didn’t help much – the lice were still with us. No nice showers and soap, just cold showers. Registered, given a metal identity disc – my number 4867 Stalag 303 – and photographed. I would love to see the photo of me scowling with a month’s growth of beard. Relieved of any paper money we had. I lost 3 Egyptian pounds, a tiny piece of paper was given as a receipt. No-one could have kept that for four years. I was given a pair of boots, too large, with holes in the uppers and not much sole or heel, trousers and a pair of Yugoslav puttees, which came in very useful when the winter snow came, and lastly a Yugoslav cap. The best of all was a postcard which said, “I am a POW, am wounded/not wounded” - I could not write a message on it – to send home. This arrived in PE three months after we were sunk. My parents had only got the news that I was alive the day before receiving the postcard.

We were not long in Marburg when about twenty of us were sent to Pettau, not far from Marburg, to work as labourers on a building site. The small camp that we were in at least had straw mattresses, sanitation (though primitive) and better rations. One Aussie (Andy) was shrewd enough to say he was a cook, so was left in camp to have a glorious loaf as our cook – I think his experience was peeling potatoes in the cookhouse. All he really had to do was stoke the fire under the boiler and make coffee, fill the boiler again for our soup – if you were lucky you got a piece of the horse’s head.

We only spent a month in Pettau and were returned to Marburg. It was August when ten of us were sent to a small village as farm labourers. This was where our lives as POWs took a turn for the better.

After an uneventful all-day train ride from Marburg (no provisions for journey) we arrived at Wies, the end of the railway line from Graz. A 5-kilometre walk took us to Wernersdorf after dusk – somewhat tired and hungry. We stopped at the first house in the village for the guard to enquire where we were to be billeted, etc. While he was talking to the “bauer”/farmer whose house it was, the wife came to the door and said, “Ein man essen.” This I understood, and before anyone could move, I was in the door, taken to the kitchen and given a bowl of soup and bread. The others saw me eating through the window and never forgave me for beating them to it. The guard persuaded the farmer to give him a loaf of bread for the other nine men in our party. These loaves were a good size, so everyone had a reasonable share.

Location of Wernersdorf (Google Maps)

We were then taken halfway up the hill to a cottage, which was to be our base for some months. Our work party comprised ten men, eight of whom were army and two naval, myself and Fred Webster, both from PE. The other guys were four English, two Aussies and two Kiwis. The room we shared had beds with straw mattresses and, best of all, a wood stove. We were given a blanket only about 4 foot x 4 foot. We then just collapsed until 6 a.m., when the hated word “raus” was shouted to us by the guard. So out of bed, dressed, taken back to the house where we were the previous evening. Ten farmers were waiting to get a worker for each of their farms. I was taken by the one who fed us the previous evening (Windischbauer) and the others were scattered all over. Two of them, an Aussie (Bob) and a Kiwi (Dick) went right up the mountain, an hour’s walk away. It was too far for them to be fetched and returned each day, so they slept on the farm from Monday night to Friday night and came down to us on Saturday evening and left on Monday morning.

Back Row Standing: Dicky Bracken; Melvin Baker; Andy Andreason; Bert Widdop; Eric Churchman; Freddie Webster.

Front Row Seated: Les Bagley Lofty Shepherd; Lex McRae; Bob Bryce

The obverse side of the photograph was addressed to Mrs W.F. Baker, 10 Irvine Street Port Elizabeth, South Africa with the following message: “Love from your loving son, Melvin”.

Below are the details of the POW Work Party in Wernersdorf:

- Fred Webster – South African - a clerk in the PE Municipality – older than me – had previous peacetime training - had done short course on RN ships based in Simonstown - after the war went back to the municipality – married late in life – had no children

- William Shepherd (Lofty) – English – married - lived in Grantham – worked as a truck driver – after the war went back to truck driving – had two daughters

- Les Bagley – English – married - sergeant in the regular army

- Albert Widdop (Bert) – English – married - lived in Keighley, Yorkshire – painter, could also paint pictures as well as houses – went back to painting – later in life went to live in Adelaide, Australia where one of his sons lived (I met him there)

- Eric Albert Churchman – English – married - Londoner – worked for a shipping company as a clerk – after the war went back to shipping and became passenger manager for his company

- Keith Andreasen (Andy) – Australian – lived in Sydney – had a factory manufacturing manikins for shops and so on – after the war retuned to Sydney – became truck driver delivering petrol –married – had two daughters – later met up with Austrian daughter from Stephanie

- Robert Bryce (Bob) – Australian - lived in Sydney – butcher – after the war had a similar job – married

- Richard Henry Bracken (Dicky) – New Zealander – had a variety of jobs – after the war became a very successful farmer and lived in Rotorua

- James Alexander McRae (Lex) – New Zealander – surveyor – after the war a professor at Otaga University, Dunedin

From now on food was not our only conversation as when we were starving – that was about all we could think about and talk about; and all the wonderful meals we could have when it was all over.

The first job in the morning was to clean out the stable, cart all the manure to the dump for distribution to the lands at a later date, feed the cows and horses (I was the only one where the farmer had horses). All the others used oxen for ploughing, and even cows for lighter work, such as harrowing. After this into the kitchen for breakfast which was “sterz”, coarsely ground yellow maize “porridge”, no sugar or milk – sometimes with ersatz coffee or sour milk (which I hated) and sometimes the stertz was topped with minced, pan-cooked pork fat. At ten o’clock we had a break and were fed bread, and if lucky, a bit of pork fat. One o’clock was the midday meal. This was usually soup, not the way we would make it, watery with bits of bread floating on top, maybe baked beans, sauerkraut or potatoes, very seldom meat. Everyone sat around the table. The food was in one dish, and all mucked out of this dish (very hygienic), soup included. We never drank water. Cider was available all the time, especially when mowing and hay-making.

In the evening we had a slice of bread, not very interesting or inspiring food, but enough to keep one’s stomach full and once again build up strength and fitness, with the long hours and hard work. Working hours in summer (8 months) were 6 am to 8 pm, six days a week; winter 7 am to 7 pm. They tried to get us to work on Sundays to feed the stock etc, but we threw the Geneva Convention at them and said no prisoner shall be forced to work on Sundays.

The farmer I worked for had four sons, no daughters. The eldest, Roman, was a private in the army at the Russian front. Franz, the second son was an SS corporal – where he was stationed I never found out, as he was the one who got leave to come home several times. Hans, the third son, was at home – bad eyesight – wore thick glasses. Paul, the fourth son, was an SS private on the Russian front. All except the third son, Hans, were married.

The second son, Franz, was caught by the Partisans in Yugoslavia and no-one heard details of what happened to him. The Partisans no doubt just shot him because he was SS. The fourth son, Pauli, got home after the war, but the Russians took him away and no-one could find out what happened, but I am sure that as he was SS he was lined up with others and shot. Roman, the first son, made it home and added a daughter to his family of four sons. Hans, the third son, was finally put into uniform but spent more time at home than in the army as he was “needed at home to help with the farm”. Hans and I got on well together. The blacksmith’s lackey was called up at the age of 17 and was captured by the Russians and put in a POW camp. He was not released by the Russians until 13 years after the war ended.

Apart from the farmers having a POW working for them, there were many Russian, Polish and mostly Ukrainian male and female workers aged 17 to 19 years. Windischbauer, my boss, had a 17-year-old Ukrainian girl, very good figure and pretty, but hygiene was not her strong point, as she smelt worse than the pigsty. Pity, as otherwise she was okay. The women did a lot of men’s work and worked for longer hours than we did.

One local woman, Mitzl, aged 40 plus, not only worked in the fields and so on, but joined me in the forests sawing down trees when Hans was called up. She would pull on one side of a cross-saw, and I on the other. The heavy axe work was left to me, but she, with a smaller axe, would trim off the smaller branches. Then the trunks were cut up into 3 metre lengths and dragged to the tracks, where they could be loaded on a wagon. In winter, the one end was put on a sled, and dragged along the snow and icy road to the farm by a pair of horses. Most of the trees I felled were chestnuts. The logs were cut up in one- metre lengths and carted to Wies, the railway station, and sent to a tanning factory.

I moved round the district where we could find chestnuts, so I met up with a lot more people than the other POWs, who never left their farms during working time.

Towards the end of the war, when the bombers came over in hundreds (one Sunday morning we counted over 900) I was about 5 miles from Wernersdorf to collect the logs we had prepared for transport. I went up to the farm house to scrounge some cider, when one bomber was in trouble with smoke coming from it. The two daughters said they hadn’t seen bombs drop and would like to know how it felt. Then the bomber returning for Italy dropped its bombs, which landed about 200 yards from us. The shock and look on those girls’ faces was a sight to see! I said, “Well, you wanted to see it.” The Austrian who was working with me was with the horses when the bombs dropped. The blast knocked him over, and the horses took off, fortunately not too far. We soon had them under control. Actually, at one time I spent more time tree-felling than on farm work.

Our first winter came early – the first snow was on the 1st of October. It didn’t last long, but made everything sludge, which was worse than snow. My boots by now were useless and I was issued with a pair of Dutch wooden clogs which kept one’s feet nice and warm but walking in the snow was quite an experience – the snow compacted and stuck to the bottom and built up until I was walking on stilts and had to stop and break it off. Going up the hill to our lager was quite a job as the slope was steep and the clogs kept slipping – in places it was two up and one down. Eventually my bauer found an old pair of his boots, two sizes too big for me with holes in the uppers but certainly better for walking than clogs. For socks I had a couple of rags which I wrapped around my feet. The leaking boots didn’t stop one’s feet from getting wet. The wet rags froze in the boots and when the boots were taken off the rags stayed frozen to the boots – took ages to thaw. My circulation was good and I didn’t suffer from chilblains or other problems like some of the lads. Finally the bauer’s wife took pity on me and gave me a pair of nice thick home-made socks of home-spun wool – what a joy.

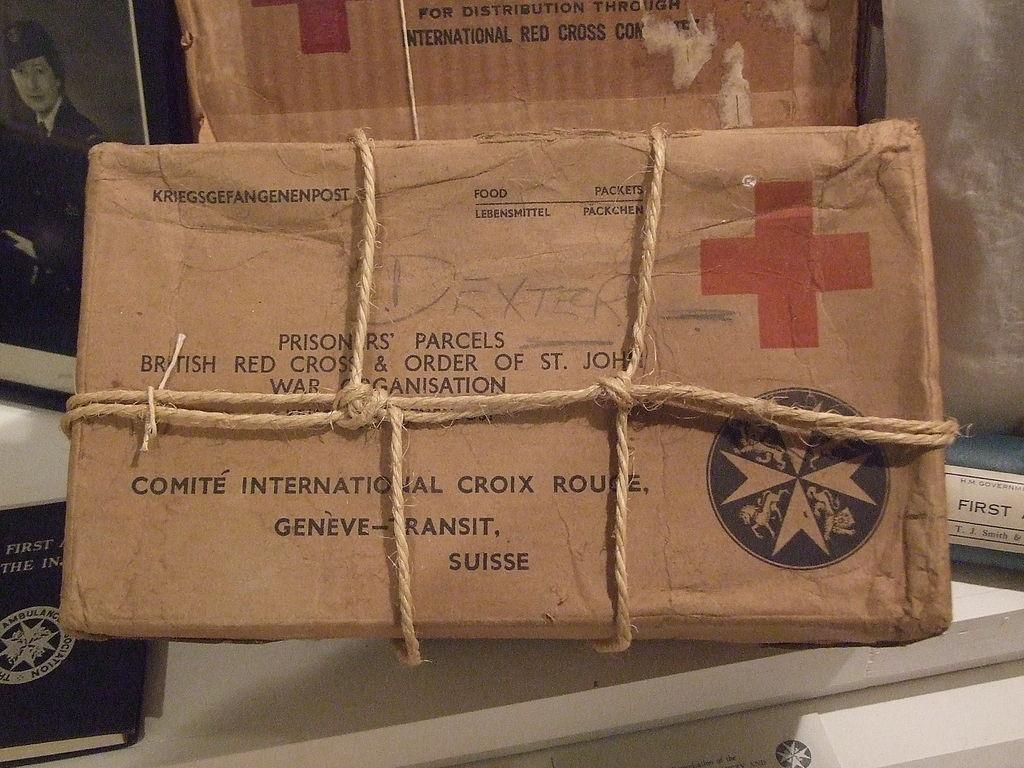

The first Red Cross food parcels arrived in October 1941. We could not believe what a lot we found in one small box [Red Cross Food parcel contents: tea or coffee, Klim powdered milk, sugar, salt, cheese, army biscuits, jam, 1 lb butter, chocolate, soap, meatloaf, bully, raisins or prunes, 50 cigarettes]. That evening when we returned to camp we were each issued with a parcel. Well, you can just imagine what pigs everyone made of themselves. The result was many nightmares. Fred Webster gave a vivid account of the sinking of the Gloucester. He started laughing and said, “Poor old Lofty, he hasn’t got his lifebelt and he can’t swim.” Les Bagley went through the evacuation of Dunkirk. He was sunk three times on the way to England, and finally finished up on a coal barge. He said, “It’s a coal barge, but it floats.” What a way to get home and then go to Greece and then get caught and spend four years as a POW.

Red Cross Parcel (Muckleburgh Collection via Wikipedia)

There were many more disturbing war nightmares. I didn’t get much sleep that night, and eventually dozed off. From now on we were better fed than anyone else in Germany. Plenty of bulk from farms, all the vitamins and good food from our parcels. This lasted until the end of 1944.

When the food parcels started arriving we received playing cards and some books. Shortly after receiving our first food parcels we received brand-new British Army uniforms - greatcoat, boots and socks, the full kit. What a treat to be properly dressed for once. We wore them in winter, but in summer it was a case of shorts, a shirt and “socals” (wooden soles with a leather top over the front half – slippery when it was wet). If we were sawing down trees I had to wear my boots.

Farming was all done by hand – no machines such as tractors. Wheat, rye and oats were all sown by hand. Maize was sown by a small planter pulled by hand – two men pulling, one behind feeding the planter. Potatoes – each one placed in a furrow by hand. Beans – sown by hand in “klompe” (clumps) in the maize land. Squash – a la beans. A small garden for lettuce, cabbages, etc was tended by the “Bauerin”. The maize land was weeded with hoes, and soil was heaped up to the stems of the plants. The same was done with potatoes. Haymaking took place in midsummer – first mowing, which was done by the men using scythes, turning and raking was done by the women. A second mowing of shorter grass took place in late summer. Hay mowed in the morning was ready for carting to the hayloft by late afternoon provided it stayed sunny and there was no rain.

Wheat etc was cut by sickle by women and tied into bundles which the men took and made stooks for drying. When well dried it was carted to the barn and all these were threshed by hand by beating on a large flat stone at knee height. The bits of the ear which broke off and still had seeds were spread on the floor and thrashed with a wooden club tied loosely to the end of a stick. It was now winnowed by a hand-turned machine after sifting. Potatoes were reaped by spade and hand, then stored in the cellar for winter. Beans – hand reaped. Pumpkins – used for pig feed were loaded on wagons and brought to the farmhouse. The seeds were all retained and turned into salad oil – a very nice addition it made to the salad. Maize – yellow - was reaped by hand and brought to the kitchen of the main bauer and being the last crop of the summer, led to a party. The kitchen was half-filled with maize up to the ceiling. The shelling was done by the farmers and their workers, who went from farm to farm. It was a community project, and when it was finished the party started – singing and dancing and, no doubt, drinking. We were not allowed to join in.

Everything was very labour intensive. Small kids also had chores to do. During haymaking one kid spent most of the day bringing cider from the cellar to the workers – it was very thirsty work. There were no toilet facilities, so to relieve themselves the men merely took two paces back and turned around. The women were not so lucky, as they had to find a bush or a ditch.

Nobody drank water – just cider all the time from morning to evening – after that I don’t know if they drank any of their home-made wine (all had small vineyards). It was ghastly, except for one small barrel which was made from the only decent grapes, which could also be eaten. The others were certainly not for the table. Apple cider and perry (from pears, which had a higher alcohol content) were used for distillation.

Once a year the farmers were allowed to distil their own schnapps. They were allowed 96 hours – the fire was kept going 24 hours a day. The first distillation was low in alcohol, so towards the end it was all put back in the still and double-distilled. The first lot that came from this was not far short of 100% alcohol. I was given a small tot and had to drink it in one go. I nearly choked and felt as though the hairs on the back of my neck were standing on end, but there was no way I was going to let the locals know that I couldn’t take it better than them.

Our guard whom we hated and for some reason did not like Andy or me – he came back from a visit to one farm totally blotto – he had sampled far too much schnapps. We thought now we had a chance to get rid of him and told the bauer in whose house we were that he had better lock us up for the night as the guard had passed out – hoping that he would report it. No such luck. He didn’t do a thing about it. So we were stuck with the sod.

Franz (second son) came back from Yugoslavia with two horses, probably commandeered, so I was now a horse knecht (worker), as old Hans still had the other horses. These horses knew exactly when it was 12 o’clock as they stopped and had to be forced to carry on. I was ploughing with them when 12 o’clock came and I got to the end of the field, turned the horses around, and as I moved the plough over, they took off at a gallop and made a nice furrow across the field. Les on whose farm we were working saw the horses and managed to stop them. They were not the easiest pair to handle.

Our horses were far better and easier to handle and knew what to do, especially when it came to pulling logs out of the forests. One day, to speed things up two great big horses (size of Clydesdales) joined us, but their handler would not let one horse at a time pull out a rather large log. So I said don’t worry – I put the mare on alone and showed him how much better one horse was than his two. He was not pleased to be shown up by an “Englander”. This was after Hans, the horse handler, was put into uniform and the two new horses had been returned. I was now horse handler. What Hans did in the army I don’t know, as he was over 60 and not very bright. He could not read or write.

Forest and river near Wies and Wernersdorf Austria (Google Maps)

Apart from farm work, being a lumber jack took up all the spare time – so no rest when the farm did not require much work. When I first started on the tree-felling Hans (son of Windischbauer) worked with me and sometimes Mitzl came along to do the lighter work. Then we also had another old man of 75 who was still fit enough to do the lighter work.

When Hans was called up it was just Mitzl and me. She now shared the hard work on the other end of the cross-cut saw. I had to chop the scarf (where you first cut into the tree – it must be in the right place so the tree falls where you want it).

When Hans (horse handler) left we had only one pair of horses. I usually had to load the wagon on my own. Wet chestnut logs are not the lightest. It was a case of getting one end up, securing it and lifting the other end. When loaded they had to be secured by chains fore and aft. I once made a stupid mistake and didn’t re-tighten the chains after going a short distance to let the logs settle, so had to get the logs off and reload. Idiot - never made that one again.

The biggest tree we had to fell was nearly six feet across and the saw was only eight feet long. Four of us tackled this one. It took ages as it had hollowed in the middle and a bit of the centre of the trunk was still there. As we sawed through, it would drop and jam the saw. So we worked the saw loose and started again until it was small enough to finish the job. They tied a rope to the handle so that two of them could pull on one side, but the Englander had to show them up. I didn’t have any rope on my side of the saw. Of course, they didn’t realise what I was doing – when they had to pull, I put extra pressure on the cutting edge of the saw so they had a harder pull than I had. It still took a long time.

We spent our first winter in the house up the hill. We arrived together with our body lice and started the battle to get rid of them. The only way was to remove clothing daily and crush them between our thumb nails. Lex had a good idea. He was going to freeze them to death, so he hung his shirt outside in sub-zero temperatures for two days, but when it thawed they were still there.

After the first winter we moved to the house where Les worked. Better accommodation, except that the place was infested with fleas. By now, having won the battle with lice, the next one started. No anti-flea powder was available. I was allowed to go to the shop as it was next to my work place and found some Lysol which we used to scrub the floor, but no help. I saw some naphthalene on the shelf and got a big packet. We spread this on our beds and it did seem to help a bit, but we now smelt of the stuff.

Every evening the first one in lit the stove. I was usually the first. Within minutes my legs were full of fleas; I went to the window and started on one leg killing dozens, next leg some, by now first leg plenty and so on until reasonably clear for the moment. Eventually the battle was won.

On getting back to camp we all made tea or coffee and consumed some of our food from Red Cross parcels. Much talk and ragging until 10 pm – lights out and locked up for the night. “Talk” was usually argumentative about which country and life in general was better than others, but we all got on very well together seeing we came from such diverse backgrounds.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.