Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

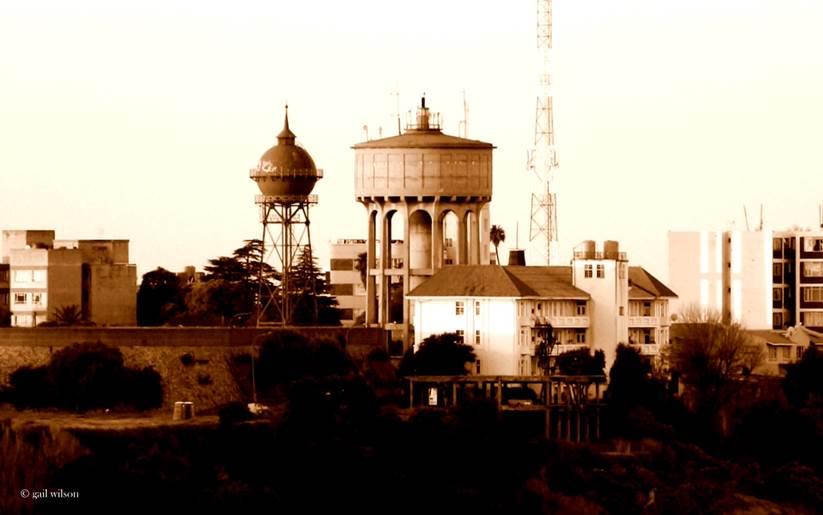

Many readers will have heard of the discovery of the original Yeoville Water Tower blueprint earlier this year. This discovery sparked a research journey which has culminated in a wonderful series of articles by Kathy Munro (click here to view series index). Below is the first installment which covers the early water supply history of Johannesburg and the origins of the Water Tower. The piece was first published in the Sep / Oct 2018 issue of Architecture SA. Thank you to Paul Kotze for giving us permission to publish. The powerful main image (copyright Gail Wilson) shows the 1913 Yeoville Water Tower to the left, the 1937 concrete water tower in the centre and Westminster Mansions in the foreground.

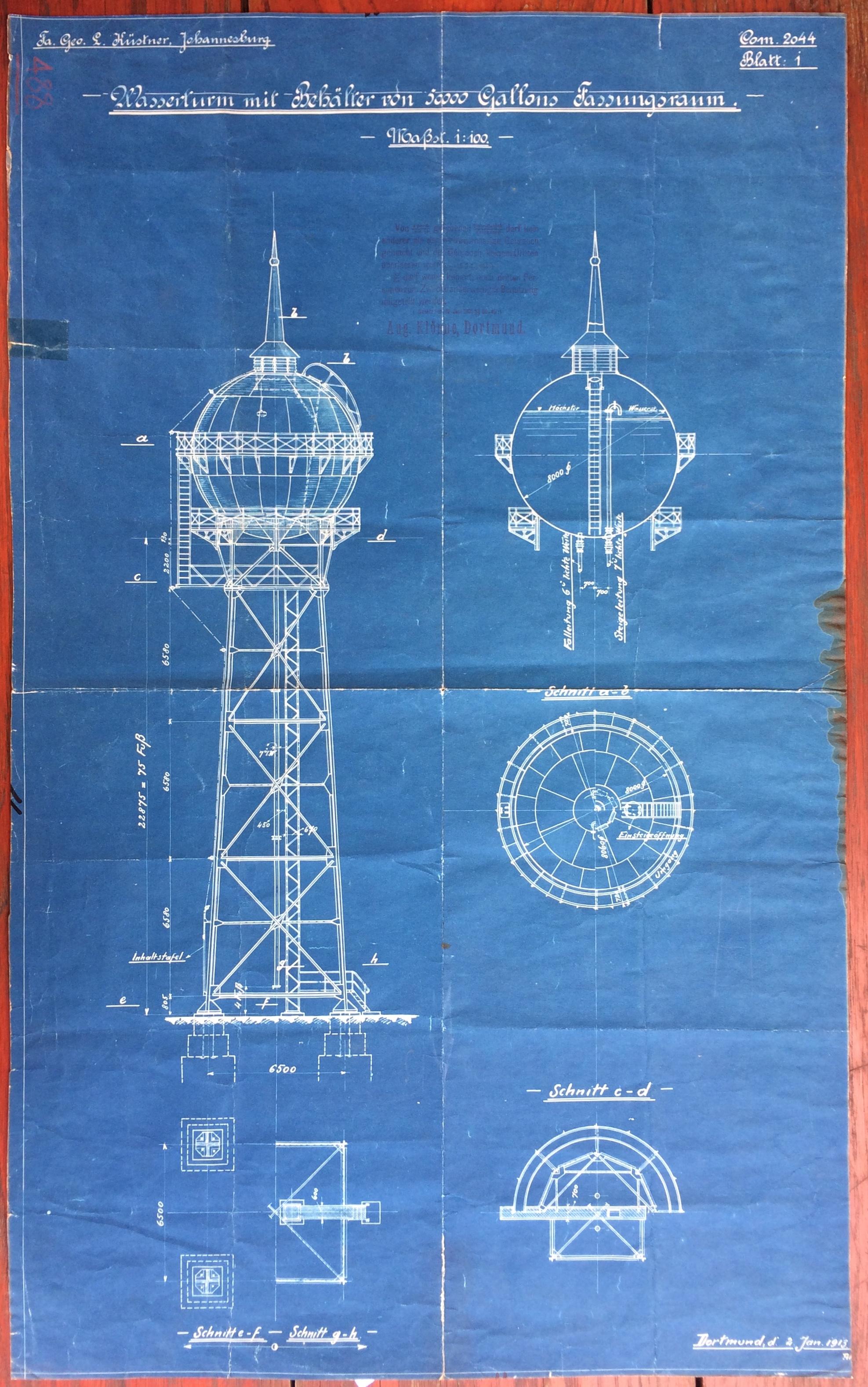

The Johannesburg Heritage Foundation awarded the Yeoville Water Tower of Johannesburg a Category A heritage protection listing in its grading exercise of 2013. Its origins have been shrouded in mystery. The Water Tower, assembled from precast steel pieces dates from 1913 and was designed by the German engineering firm Aug. Klönne, of Dortmund, in Germany.

Yeoville Water Tower from the Observatory Ridge (The Heritage Portal)

Yeoville Water Tower from Da Gama Park (Kathy Munro)

A blueprint of the architectural structural drawing (400 x 650 mm) has recently been found in Johannesburg. Here is a case of a special archival find that was perceived as having no obvious value because its importance was not recognised; yet as research unfolds, its relevance is realized and it becomes the missing piece in the jigsaw puzzle of a Johannesburg story.

Kathy Munro with the Yeoville Water Tower blueprint

The Discovery of the Blueprint

The appearance of the blueprint in Johannesburg, solves a mystery of the origins of Johannesburg's water tower on the Yeoville ridge, with its distinctive spherical-shaped crown water storage tank. The blueprint was a non-descript item purchased on a general Johannesburg auction sale, hidden at the bottom of a box. The earlier provenance is not known and there are no Johannesburg official municipal stamps on the work. Mr. James Findlay, a specialist map and document auctioneer, brought the print to the author’s attention. The significance was quickly realized as no original drawings of that particular structure have been found before.

Yeoville Water Tower Blueprint (Kathy Munro)

The Yeoville Water Tower is located in Yeoville, in the south-east corner of the suburb on the Yeoville Ridge. It is on the south side of Harley / Durban Street, close to Percy Street, almost at the intersection of Cavendish Road, where Harley, Percy and Durban streets meet. It is stand No. 1217. It is in close proximity to the three Yeoville reservoirs. Based on Holmden’s map, the Yeoville Water Tower is actually located within the suburb of Bellevue.

Yet, as it is known as the Yeoville Water Tower, I shall stick with that title. Yeoville is as much a state of mind as it has become a metaphor for a certain Johannesburg style and period. The suburb of Yeoville was proclaimed in 1890, four years after the founding of Johannesburg and was developed by Thomas Yeo Sherwell, who came from Yeovil, Somerset, England hence there is a question as to whether he named the suburb for himself or his English home town. As a suburb it had the advantages of both proximity to central old downtown Johannesburg and a high elevation. The Yeoville ridge, (plus the Highlands ridge, leading eastward to the Observatory ridge), offered a salubrious and healthier location above the dust of the mining town.

View towards the Yeoville Ridge (The Heritage Portal)

The purpose of the Water Tower

The Yeoville Water Tower is at 1805m above sea level. Water tanks for storage can be traced back to ancient civilisations such as the Indus Valley (3000 to 1500 BC); medieval castles used water tanks to withstand sieges, but the concept of a modern water tower with an elevated tank came into its own during the 19th century. In Johannesburg there is another distinctive tower across the valley to the south, the Fairview fire station lookout. The two dominating public utility towers of the east are almost within shouting distance for the conversation about the history of Johannesburg’s public utilities.

The Fairview Fire Tower (The Heritage Portal)

Looking towards the Joburg skyline with the Fairview Fire Tower on the right (The Heritage Portal)

The problem of water supply to Johannesburg

Johannesburg is unique in its location, with no major river running through the town or in close proximity. Initially, following the establishment of Johannesburg as a mining camp in 1886, water was obtained from local wells, springs and spruits or sourced elsewhere and transported to users in a water cart. Considerable quantities of water were also required for the processing of gold-bearing ore, particularly after the MacArthur-Forest cyanide recovery process was introduced. Johannesburg is situated on the southern African continental divide and the ridges of the Witwatersrand are defining geographical divisions; water run-off ultimately drains north towards the Limpopo River and east to the Indian Ocean, south to the Vaal towards the Orange River and the Atlantic Ocean. However, the Vaal River is more than 100km to the south of Johannesburg and whilst, ultimately, the construction of the Vaal Dam proved to be the consistent and stable solution to a water supply for the Witwatersrand, water in sufficient quantities for mining and human consumption remained a challenge for several decades in the early history of Johannesburg.

Vaal Dam (Lennie Gouws)

Solving the problem - a thumbnail history of water management in Johannesburg

In December 1887 a waterworks concession (though not a monopoly) was given to Mr. James Sivewright (1848-1916), with his company the Johannesburg Waterworks, Estate and Exploration Company Limited, committed to laying pipes to supply water to central Johannesburg businesses and to the new north-eastern residential suburbs. Their sources of water were the springs at Harrow Road and another spring in New Doornfontein. These were called the Northern Spring or Fountain and the Southern Springs. The first piped water came from the spring at Harrow Road and supplied the town from 1888. Reservoirs and water tanks were part of the water solution. A reservoir in the suburb of Berea at Harrow Road off Abel Road was constructed below the spring in the present Donald Mackay Park. The first balance sheet of the company showed debts exceeding income and the when the first engineer and manager of the company, Mr. G R Andrews took up his position in 1889 he found a dismal state of affairs. In the same year Mr. Barney Barnato (1851-1897) acquired the controlling interest in the company and in 1895 the Waterworks Company became a wholly owned subsidiary of the Barnato company, the Johannesburg Consolidated Investment Company. Contaminated water though, was the cause of typhoid deaths in Johannesburg in 1896 and the fire brigade was unable to fight fires adequately because of inadequate pressure.

In years of drought, for example in 1892, and in 1895, water became a scarce and expensive commodity, sold by the bucket while hotels supplied soda water for the hand basins. Following the 1892 drought more reservoirs were built. The city was and still is very dependent on the storage capacity of its reservoirs in Yeoville, Berea and Parktown.

It is evident from the early Johannesburg water saga, that the issue of public versus private ownership was hotly debated. In 1895 a Government commission was appointed to investigate and report on the question of a pure water supply for Johannesburg, but the political conflicts of the decade overshadowed those practical but vital issues of water, public health and sanitation. Permanent solutions to the water problems were not feasible until the new century.

Water as a private or a public utility

In 1901, with the Anglo-Boer [South African] War nearing an end and Johannesburg town administration capably managed by Mr. Lionel Curtis (1872-1955) as town clerk, discussions and commissions tackled the water problem. The solution was seen to be the bulk purchase of water sourced from further away. In 1902 the Rand Water Board was established. By 1904 Johannesburg’s population exceeded 155 000. The private enterprise model and exploitation of an essential resource gave way to public ownership, and the view that water was far too essential to be other than a public utility prevailed. It was not an easy transition from private to public ownership, and the greatest opposition came from the ‘Johannesburg Waterworks Company’ as the largest and most important of the local water companies with the most to lose. It was only in 1905 that an arbitration court ruled that the assets of the various water companies, including the ‘Johannesburg Waterworks Company’ should pass to the Rand Water Board.

The Rand Water Board became responsible for sourcing water in bulk and the Johannesburg municipality’s Engineer’s Department was responsible for distribution and reticulation within the town. The reservoirs of Yeoville and Berea were critical components of the system and this was where the Yeoville Water Tower fitted into the picture.

Yeoville Water Tower from the roof of San Remo (The Heritage Portal)

Linking population growth and suburban development to satisfying the demand for water

By the early 20th century the town was expanding, with many new townships declared and developed in rapid succession. The new suburbs of the 1890s included Braamfontein / Clifton (1890s), Parktown (1890), Rosettenville (1889), Yeoville (1890), Bellevue (1895), Hillbrow (1895), Turffontein (1897), La Rochelle (1895), Booysens (1887), Auckland Park (1893), Fordsburg (1893), Mayfair (1897), and Albertsville (1896). There was a hiatus in property development during the Anglo-Boer (South African) War but following the restoration of peace and the British occupation of Johannesburg the town took on more of a look of permanence. Johannesburg was then, as now, a magnet for new arrivals, immigrants and migrants. The suburbs of the 1900s included Brixton and Bezuidenhout Valley (1902), Westcliff, Upper Houghton and Norwood (1902), Parkhurst and Observatory (1903), Orange Grove and Sophiatown (1904), Parkview and Parkwood (1906). The suburban spread was geographically stretched.

The municipal boundaries were extended in 1901. In 1910, the total population of Johannesburg stood at 220,304. The reorganisation of municipal government meant that the supply of water had to be a managed resourced. The growth in population, the building of suburban homes and the need for a water infrastructure, meant that the Town Engineer’s Department needed to respond to increased demand and rising water draw-off. There needed to be a satisfactory pressure at the water hydrants and also an assurance that water was potable. A water tank positioned at a height operated in conjunction with water reservoirs and pumps, was part of the solution to the problem. There had been a tank in Yeoville from 1903 but greater and more effective capacity was required. The Yeoville ridge was the natural location for both water reservoirs, water tanks and towers as this was the closest elevated spot to central Johannesburg. In 1905 there was a three million imperial gallon (13 638 270 l) high service Yeoville reservoir and a one million imperial gallon (4 546 090 l) reservoir at Harrow Road.

View of the City from Yeoville Ridge (The Heritage Portal)

The origins of Johannesburg’s Yeoville Water Tower

In 1913 it was decided to expand the capacity of the Yeoville reservoir by raising the walls of the reservoir by an additional six feet (1,8m). The annual report of the Town Engineer for 1913 reported on this project and, in addition to this, a decision had also been taken to install a new water tank as well as a pumping plant for providing additional storage and so improve pressure at the fire hydrants. Andrews, the town engineer, reported that tenders had been called for a water tank 75ft (22.86m) high and having a capacity of 50 000 imperial gallons (just over 227 000 l). This was an improvement on the existing elevated tank which was only 35 feet (10.668m) high. We can assume that the old tank was the 1903 water tank, which from a photograph, appears to have been a rather ordinary water tank on stilts. The tender accepted for the new tank was for an amount of £1,436 (£155,852.78 in 2017 or equivalent to approximately R2.65 million) and by 1913 the construction of the elevated Yeoville tower tank was well under way. The town also purchased the motor and pumps for £315.15s; (equivalent to £34,296.30 in 2017 or R583 000) the purpose here was to pump water into the elevated tank.

Yeoville Water Tower (The Heritage Portal)

Yeoville Water Tower Pump House (The Heritage Portal)

The 1914-15 annual report (published in 1916) noted that the “tank” had been completed in February 1914 but had not yet been put into operation owing to the delay in the delivery and installation of the pumps and motors. The tank is described as “a sphere with a diameter of 16 feet 6 inches (5.06 meter) and has a capacity of 50 000 gallons” (227 304.5 l). In effect the investment in this project totaled £1,751.15s (or £190,149.08 in 2017 = R3,215,129).

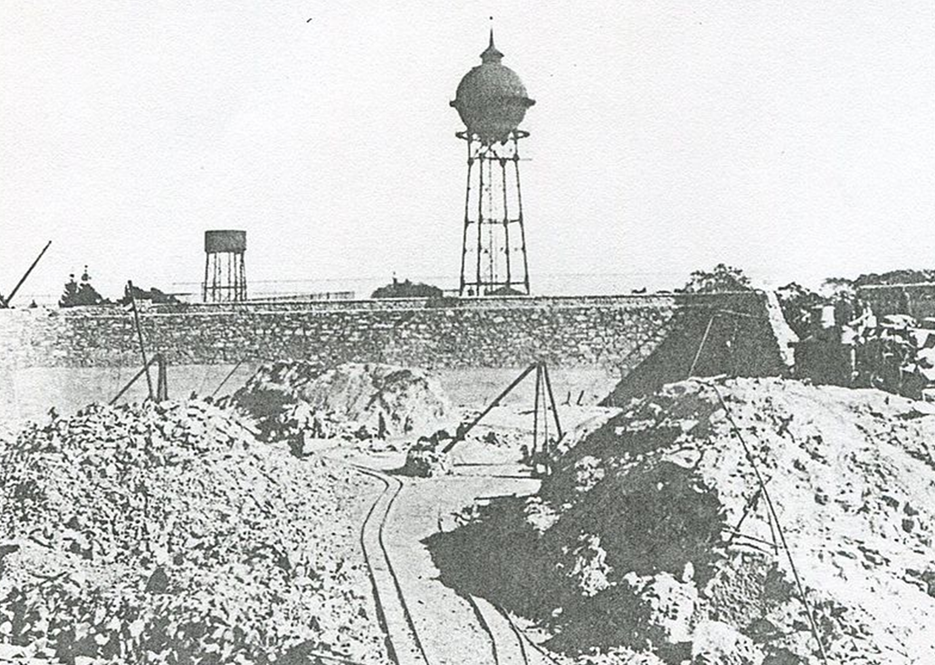

The 1922 photograph (in the Museum Africa archives), shows both the Yeoville Water Tower and the earlier (probably 1903) elevated water tank, with a further new reservoir under construction in the foreground. It is interesting to note the proximity to the Yeoville reservoirs and the Yeoville Water Tower and tank. In 1923 a new reservoir at Yeoville was constructed and in 1937 the round concrete water tower, close to Westminster Mansions, was erected.

Construction of the reservoir (George Grant and Taffy Flinn)

1937 Concrete Water Tower (The Heritage Portal)

By 1951, there were two reservoirs in Yeoville with a storage capacity of 14 million imperial gallons (63 645 260 l) and two elevated tanks with a storage capacity of 330,000 imperial gallons, (1 500 210 l), plus two reservoirs in Berea with a capacity of six million imperial gallons (27 276 540 l). Quantity and quality of water continued to be an issue and a solution ultimately adopted was the chlorination processing of the water.

Limited edition prints of the Water Tower can be purchased from the Johannesburg Heritage Foundation (only a handful left). R400 or R500 depending on the number ordered. Email Eira - mail@joburgheritage.co.za.

Kathy Munro is an Honorary Associate Professor in the School of Architecture and Planning at the University of the Witwatersrand. She enjoyed a long career as an academic and in management at Wits University. She trained as an economic historian. She is an enthusiastic book person and has built her own somewhat eclectic book collection over 40 years. Her interests cover Africana, Johannesburg history, history, art history, travel, business and banking histories. She researches and writes on historical architecture and heritage matters and is well known for her magnificent book reviews. She is a member of the Board of the Johannesburg Heritage Foundation and is a docent at the Wits Arts Museum. She is currently working on a couple of projects on Johannesburg architects and is researching South African architects, war cemeteries and memorials.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.