Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

Port Elizabeth, like so many South African towns, suffered severe water shortages as it developed during the 19th century. It was the duty of John Gamble, the Colonial Hydraulic Engineer, to sort out such problems, and for PE his solution was to build a weir on the Van Stadens River, linked to the town by a 30-mile-long pipeline. John Hamilton Wicksteed, AMICE was selected for the post of Resident Engineer and arrived in Algoa Bay on 29 December 1877 aboard the vessel "Edinburgh Castle".

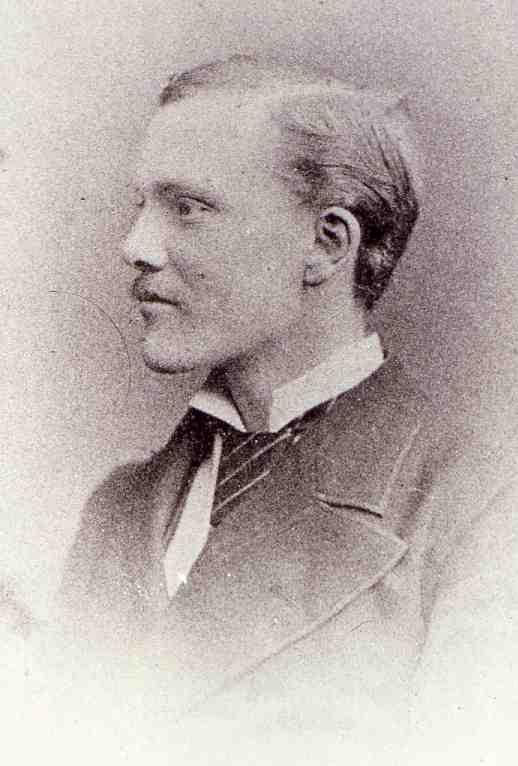

John Hamilton Wicksteed

Wicksteed, born at Leeds on 21 January 1851, was the fifth son of the Reverend Charles Wicksteed. When he was fourteen he was sent to the University College School in London. Two years later he was articled to the engineer Edward Filliter, MICE, of Leeds, with whom he remained as a pupil and assistant for a period of ten years and by whom he was employed on several works of water supply and sewerage engineering.

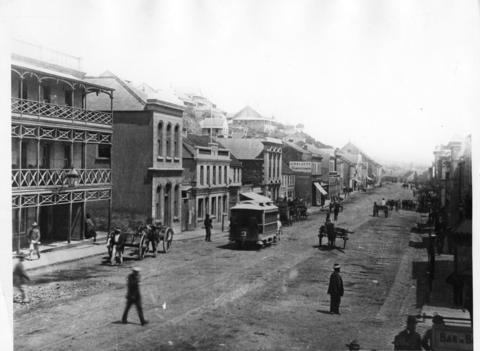

It is interesting to read his comments on seeing Port Elizabeth for the first time: “Port Elizabeth, I am sorry to say is rather like a quarry in outward appearance. Nothing more uninviting could be conceived: ugly houses and warehouses, and broad, hot streets creeping up the side of the hill, and not a spot of green anywhere.”

Photograph of Port Elizabeth in 1870 (DRISA)

On his arrival and full of enthusiasm, Wicksteed proceeded to the Town Hall, making himself known to the Town Clerk, whom he described as "a nice old gentleman with a white beard", and to the Mayor, Pearson.

A later shot of the Town Hall

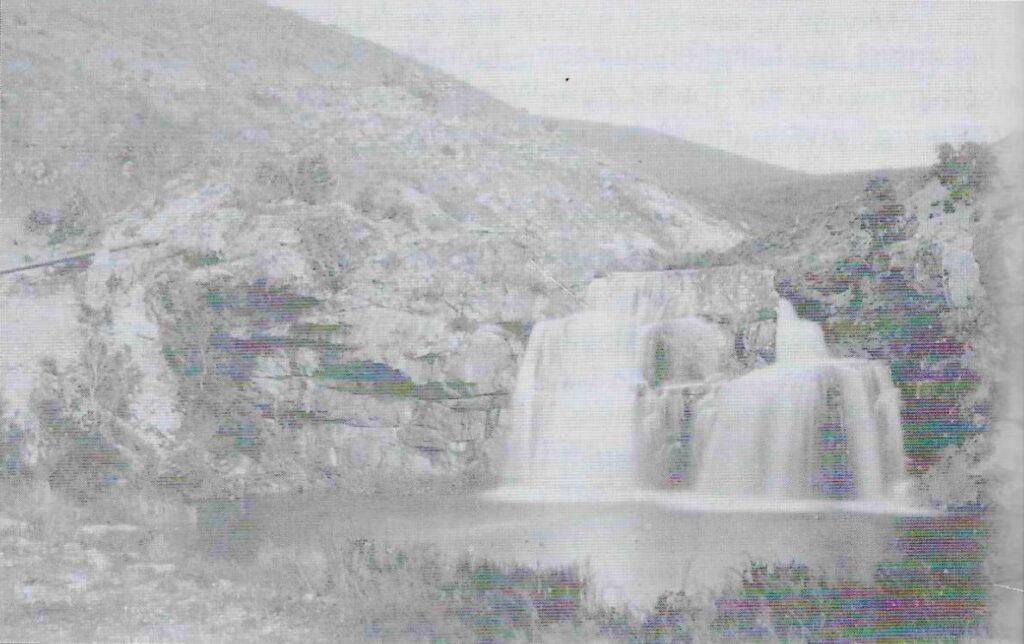

A few hours later Wicksteed was in the saddle for a rough ride, under a hot sun, to the Nali Waterfall in the Van Stadens River Valley, where soon afterwards he set to work on the necessary surveys for a complete determination of the pipe track. With the contracts awarded, work on the scheme commenced in 1879. He was meticulous in his supervision, the strictness of which proved often trying to the men. But Wicksteed had an easy, good-humoured way of securing adherence and industry among his motley gangs of labourers.

Nali waterfall below the weir on the Van Stadens River (Sourced by Casual Observer)

An example of this once occurred when he himself, working in the unceasing rain to set out the pipe route, scrambling over slippery rocks and plodding through long grass and drenching bush, encountered one of the European workmen, lately arrived from the Bay, who announced his intention of going back as such work was not "fit to turn a dog to". He was answered that he was quite right, that men were wanted and not dogs and that if the aggrieved person did not feel himself as good a man as the rest, he had better go home. After meditating five minutes on these words, the man set to work again and accomplished more than any of the other workmen that day, also working well subsequently.

During the three year contract period Wicksteed stayed at Lukin’s Camp near the weir site. The weir was constructed across the bed of the river, damming up the water to a depth of seven feet (see main image).

He had many discomforts to endure. Once after two damp nights fifty loaves of bread in a bag went mouldy; salt meat often rotted; a water cart broke a wheel and spilt all its contents when they were working on the pipeline some distance from the river. On another occasion the cook fell asleep and burnt the bottoms out of a kettle and two saucepans!

Access to the pipeline route was naturally difficult and various methods had to be adopted to get the pipes to their positions. Where it was found practicable to form a track of sufficient width amongst the rocks, oxen were employed to drag the pipes into position. About one-third of the pipes had to be brought down a steep decline of about 300 feet into the gorge, by way of a narrow path cut diagonally down the side of the gorge.

In the descent the pipes were lashed to sledges and manoeuvred down by labourers, at some places at considerable speed. The path was narrow and the gorge precipitous and it was feared that many of the pipes and their handlers might come to grief, but the work was carried out with remarkably few casualties.

Off duty in Port Elizabeth, Wicksteed appears to have been a sociable young fellow. He became a member of the Port Elizabeth Club of which he wrote:

Our Club is the best in South Africa. It is the only institution that makes the town liveable in for single men. Anybody who is anybody belongs to the Club. I dine there as a rule for company. There is a large common dining room table as well as small ones. Dinner costs me four shillings a time.

In one of his several letters, Wicksteed mentions that he had called on Miss Virginia Isett, Principal of Collegiate School. At weekends he went out to the River Club at Swartkops where he found a "regular clubhouse with beds and private rooms and an excellent table d'hote. It is a favourite resort on Saturdays for local merchants. There is a little jetty in front from which you can take a dive before breakfast."

At length the contract was completed and the first water was delivered to the Market Square in September 1880. For the unofficial opening, four fountains, playing at one time with a jet of 90 to 100 feet, watered dry and dusty Port Elizabeth. "It must have been a proud day for Mr Wicksteed", wrote the Eastern Province Herald. For many of the residents, to have running water in their homes, after years of struggle to obtain clean water, must have brought much joy and wonder.

Market Square 1880s (Sourced by Casual Observer)

Wicksteed took up permanent residence in Port Elizabeth and was appointed Town Engineer, which was surely a fitting reward for his diligent service. Sadly however he did not enjoy his success. In a letter to his mother on 11 August 1881 from Humansdorp, he complained of feeling ill and told her that he had resigned as Town Engineer due to overwork and it was evident from the letter that he was suffering from extreme depression.

On 16 August 1881 he left his office at the Town Hall in the middle of the morning and was never seen alive again. After he had been missing for three days, search parties scoured the district and it was not until the following Tuesday, 23 August, that the search party found his body close to the bush in Happy Valley. He had shot himself and the revolver was still gripped in his right hand. He was buried in the cemetery at St George's Park. Rocks were brought down especially from the Van Stadens River gorge and laid on his grave, and his family in England sent a marble tablet.

In his condolences to Mr Wicksteed’s father, the Mayor wrote:

By the death of your much-lamented son, this Corporation has sustained the loss of one of its ablest, most diligent, and most useful officers; one, moreover, whose name will for all time be associated with one of the greatest and most efficient enterprises ever yet undertaken by a Colonial Municipality.

It was a sad ending to a promising career.

David Raymer is the author of Streams of Life, The Water Supply of Port Elizabeth and Uitenhage.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.