Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

This article reflects on the influence of South African ethno-photographs on the picture postcard industry together with a reflection on their individual histories.

Most picture postcards at the turn of the 19th century had a strong photographic theme where publishers of the picture postcard relied on the original photograph for commercial purposes.

Whilst picture postcards produced an almost endless line of visual themes, this article focuses purely on photographs taken of our very own people at the turn of the 19th century, which were then produced into a commercial end-product, namely the picture postcard.

Photographs, as produced on these picture postcards cards, are original images that today play a primary role in our history, both at a visual as well as cultural historical level. In a South African context, these images have sadly not received the attention they deserve.

The visual evidence, as presented on these cards, is not based on any hearsay but rather undeniable visual evidence which was produced first hand while events and changes in society were unfolding during the turn of the 19th century. Today, these miniature historical records of life at the time, provide us with a rich reflection on our own ethnic/cultural history.

Most picture postcards would have publisher details imprinted on them but sadly photographers responsible for capturing the original images are largely unknown today.

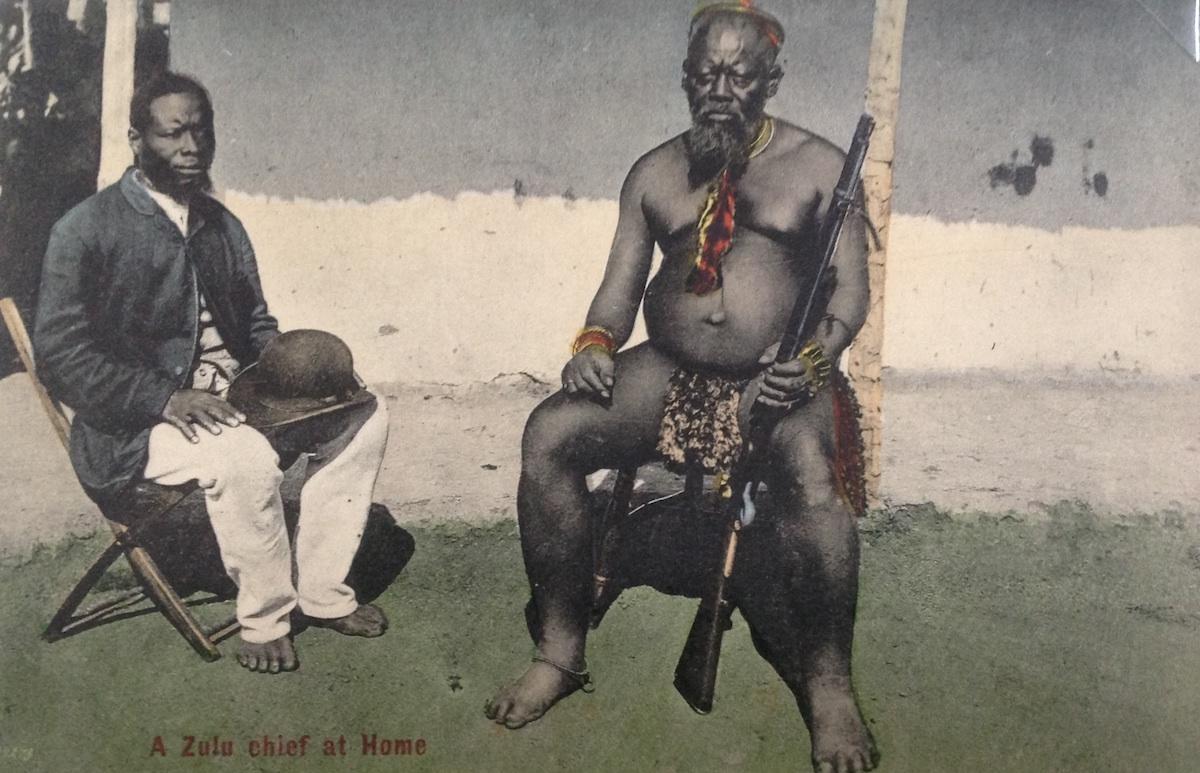

Chief Inkosi Ndlokolo kaFaku Ngcolosi. Significant in this image is the chief in traditional attire holding a rifle whilst his assistant (probably an interpreter) is dressed in European clothing. Card published by Sallo Epstein (Durban). Hand coloured card Circa 1905

Ethno-Photography defined

Ethnographic photography has had a place in photographic history since the invention of photography. The western nation was curious about people in places far away, which resulted in photographs of indigenous people being produced since the mid-1840s.

In simple terms, ethno-photography can be defined as photographs of any indigenous culture that is ethnically and culturally different to that of the photographer.

Considering the above elementary definition, we are actually all modern day ethno-photographers in our own right in that, when we travel, we capture images of cultures different to our own. For example, the author recently travelled to Accra (Ghana) where he photographed local fishermen pulling in their fishing nets from the beach. For the immense task at hand, the rhythmic chanting by these some 30 locals acted as motivation. These resultant photographic images could be described as contemporary ethno-photographs.

Also, ethno-photography does not only refer to photographing indigenous black populations. Although less common, it may also include photographs of white cultures. Many ethno-photographs were also staged resulting in some Eurocentric condescending photographs being produced.

There is no established style in ethno-photography. It may present formally posed photographs or the more spontaneous snapshot photographs.

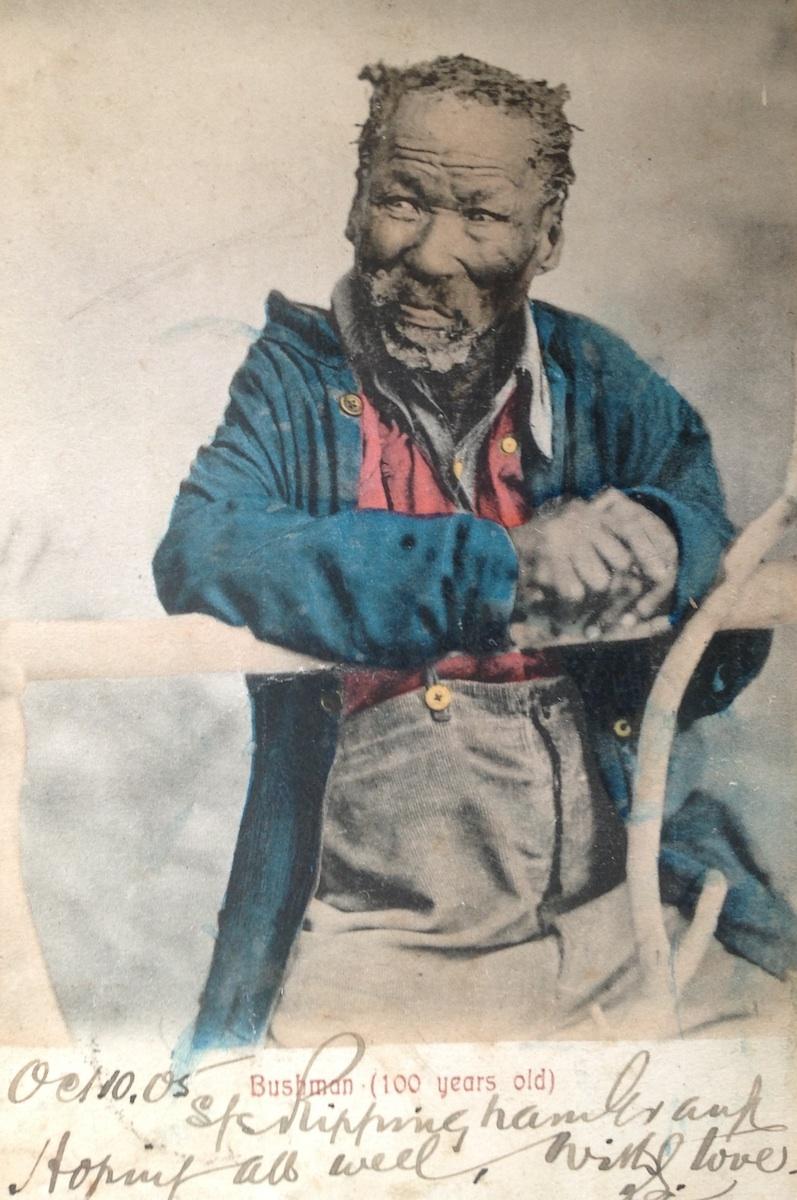

The author’s favourite of them all. The facial expression of the man speaks volumes. Card published by Cape Town based P.B.C. Dated October 1905. A Hand coloured card that was posted to New Zealand

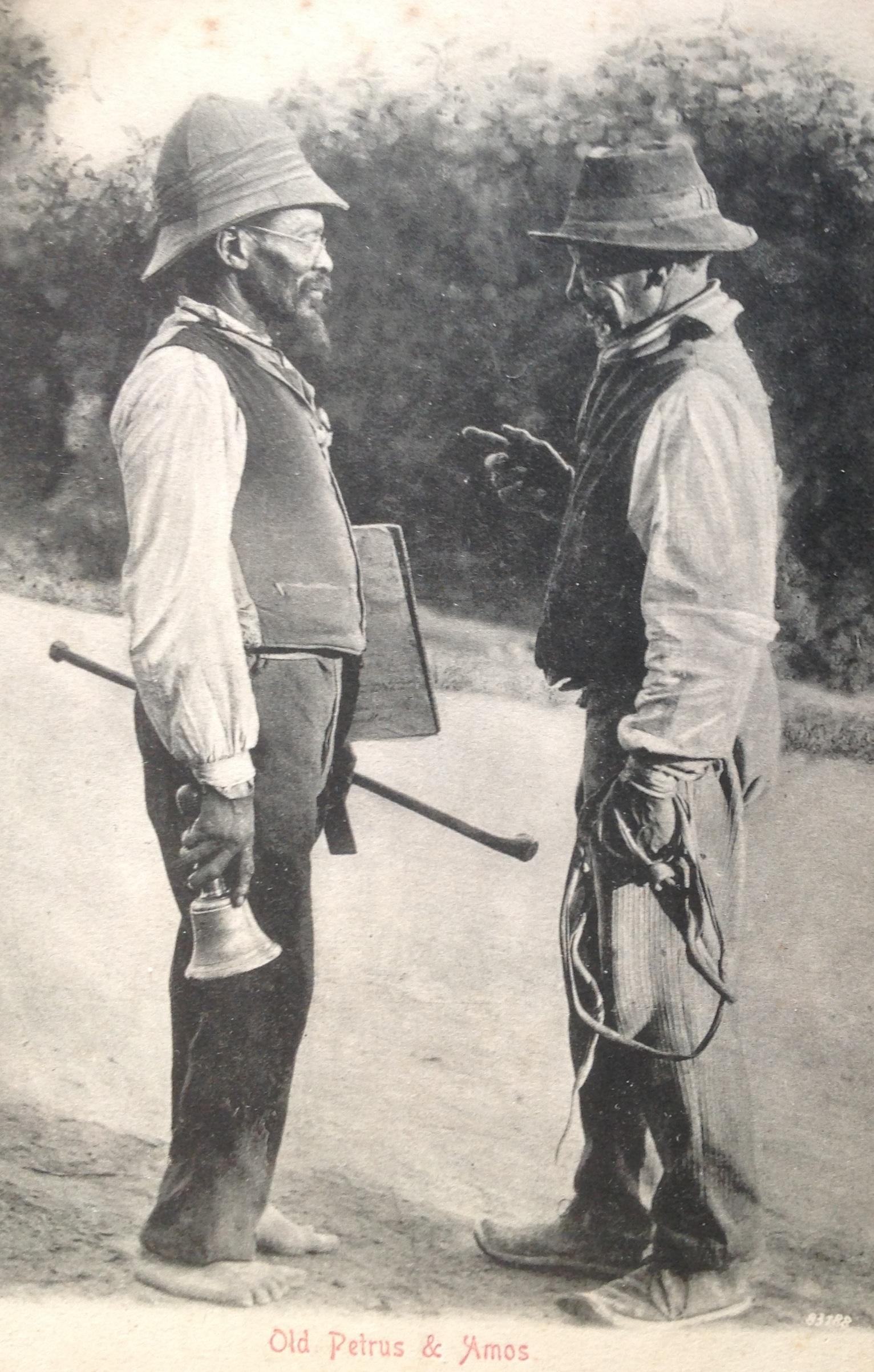

This photograph seems so natural that it raises the question as to whether the two individuals actually posed for the photographer? The whiplash held by the man on the right suggests that he may have been an ox-wagon handler whilst the man on the left, with his 1880s pith helmet, may have been a town crier. Photographer – T.D. Ravenscroft. This is the only image in this article where the photographer’s name has been recorded. Circa 1905

Photographers who focussed on ethno-photography presented their own bias or documentary styles in that the visual and psychological interpretation of the photographer played a vital role in how the culture of the indigenous people was captured.

Ethno-photographs are often images of a person seen primarily as a depiction of a “type” rather than an individual portrait study resulting in the social distance between photographer and his subject often being observable when studying the actual photograph.

The photographs produced from the undiscriminating lens rather than the selective human eye, however fudged or posed, possess an inadvertent truthfulness about them. The uniqueness of these images is undeniable – some even have a sense of theatre about them.

Today, ethno-photographs may contribute to:

- Visual anthropology – which, amongst other, utilizes photographs to analyse and interpret ethnographic data;

- Cultural anthropology – Seeks to understand the identity of a culture and provides a rounded view of the knowledge, customs and institution of people.

Ethno-photographs had a strong colonial influence during the late and early 19th century in that it was often the colonialist photographing the colonised. Photographs were mainly produced by Europeans living in, or visiting South Africa. The primary purpose and intent of the “picture postcard photographer” was to capture images for commercial reasons.

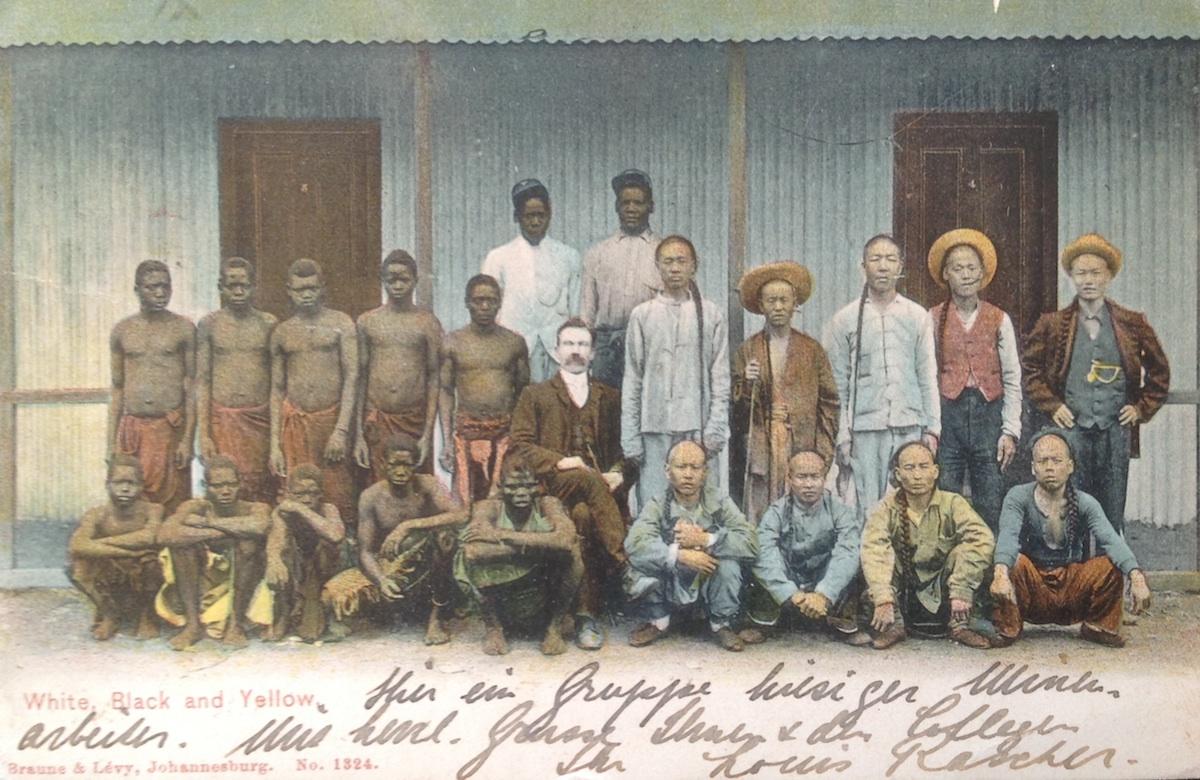

A significant image in that it portrays not only three different cultures namely black, white and Chinese but also different levels of social standing. The Chinese are dressed more elaborately compared to their younger looking African counterparts. The European dressed black men standing at the back clearly have a higher social standing compared to the Chinese and remainder of the black group. Card published by: Braune & Levy (Johannesburg). Posted to Germany during February 1907 - hand coloured card

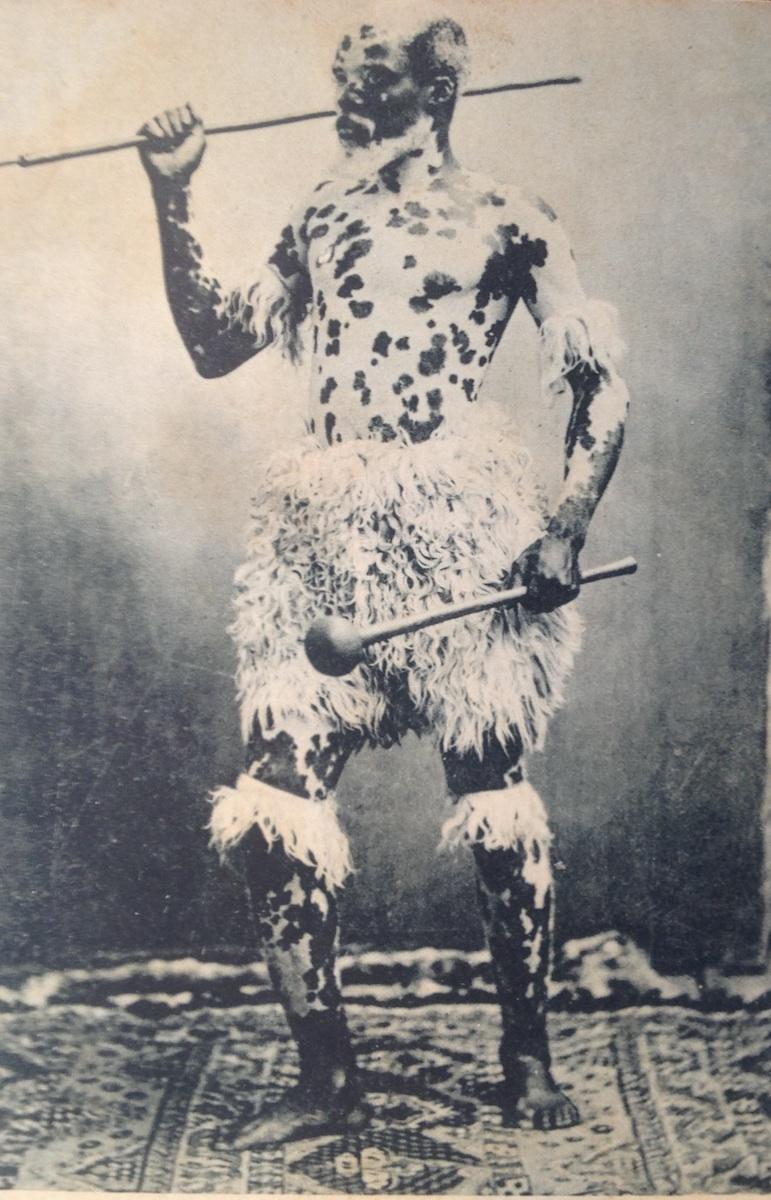

Studio photograph of a man with a skin condition referred to as Vitiligo caused by loss of pigmentation resulting in white patches developing on the skin (due to loss of melanin). Sadly the inscription, “a freak of nature” suggests that there has been no attempt to understand the condition. The commercial curiosity value was more important. The positive off-spin of this is that we are left with a historical photograph of this nature. Card published by WS (Details unknown). Circa 1907

Stevenson & Graham-Stewart (2001), state that Indigenous subjects usually struggled to retain their dignity and composure in the exploitative lens of the European traveller, tourist, scientist and commercial photographer. In the instances where the sitter’s humanity survived the racial prejudices and technology of the time, the resultant images survived to become historical records and can today be defined as proactive and even passionate works of art.

The process of taking an ethno-photograph entrenched the photographer’s position of power and often his alienation from the subject or sitter. It has been suggested that there was a strong resistance amongst black people to be photographed in that the concept of the photograph, or the technology behind it, would have been foreign and therefore intimidating.

Picture postcard images are not of the same quality compared to the original photographic images, but they remain significant nevertheless in that they provide evocative human portraits captured at a time of rapid change in Africa, leaving us with their aesthetic merits as well as their historical significance.

The wonderful diversity presented in South African ethno-photographs has a powerful presence in that the photographs express deep-seated connection with our country and the customs that gave our people their cultural identities.

Ethno-photographs have also been described as “exotic” images purely because they presented the reality of people in countries that most of the western population would never visit. The exotic notion in this context is therefore a western one. Postcard publishers relied on the “exotic” photographs to bring home the reality of the bigger world at the time.

Photography became the proof that the “exotic” was no longer the creative travelling painters or the sketchers tricking the viewer. Ethno-photographs instead became the affirmation of the truth.

Following the great cultural transformations of the present, namely the abandonment of traditional dress in favour of cheap eastern clothing, ethno-photographs present a vanished world of peculiar costumes and traditions.

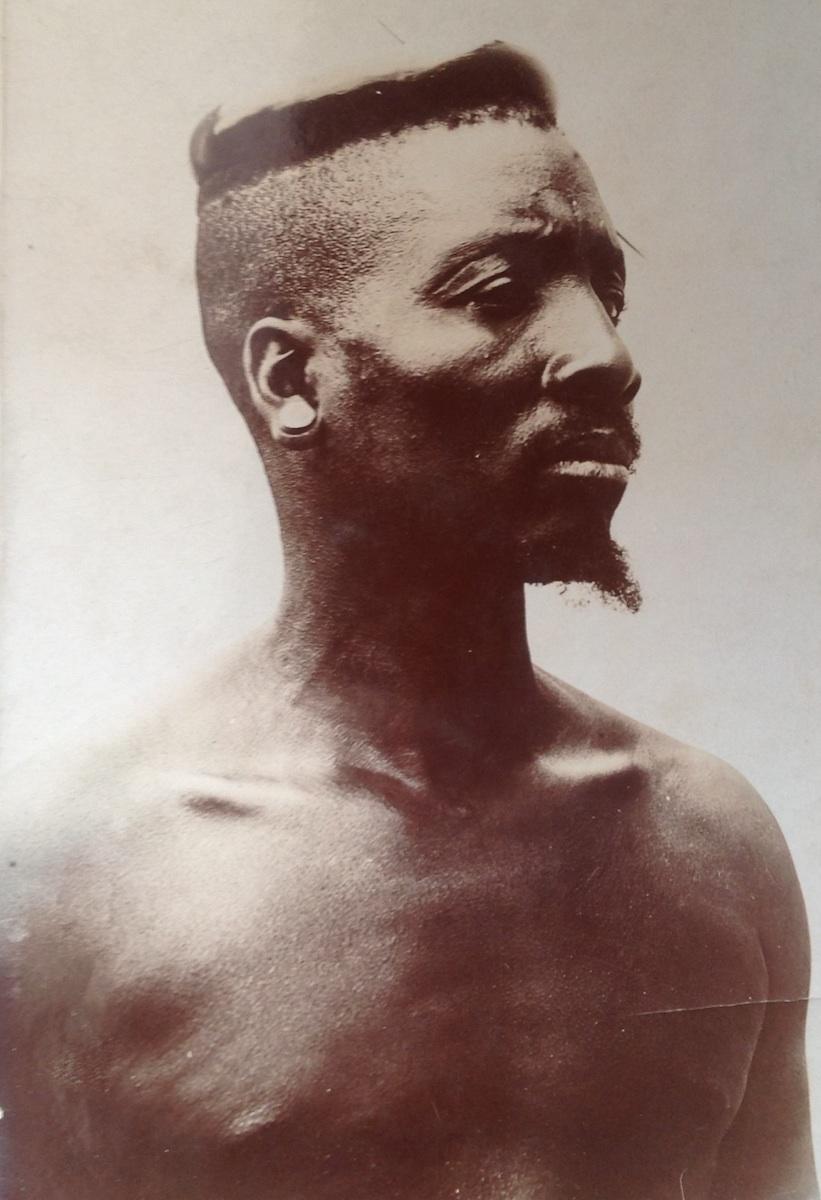

Real picture postcard produced by SAPSCO of a Zulu man. A pencil inscription on the back of the card suggests that this may be Bambatha himself (Bambatha rebellion took place during 1906). It is highly unlikely to be a card from that era in that this card dates from around 1912

Ultimately the initial narrative of a lost world, as presented in these images, was less about the subjects then the ones intended to be thrilled or titillated by them – the recipient of the postcard. It may now be argued that with ongoing modern-day research, this stance has now been inverted.

The picture postcards also include records of the naked body in all its postures from around the world. Some South African photographic cards were also produced of bare breasted women in their traditional and natural settings. The nature of these images did not have the same sexual undertone, or so it is assumed, compared to the Eurocentric full-figure nudes as produced mainly by the French. The intent with most of these images was an honest reflection of the cultural ways and dress at the time.

Sadly, little is known about the identities of the photographers of South African ethno-photographs that had their images produced into picture postcards, so much so that only one photographer could be identified in the 14 images included in this article.

Malcolm Corrigall, a photographic historian and researcher at the University of Johannesburg, is currently conducting research on the photographer Minna Keene. In the mid-1900s Keene published several picture postcards which reproduced her photographs of the 'Cape Malay' community. Keene was born in Arolsen, Germany in 1861 and moved to England around the late 1870s/early 1880s (Corrigall, 2018).

A sensitive question is, what did the subject or sitter receive in return for posing for the camera – ultimately most photographers took ethnic photographs for commercial reasons.

South African ethno-photographic images, as produced on picture postcards, in themselves provide for a multitude of potential sub-themes, namely hairstyles, daily activity, mining activity, traditional dress, jewellery, regalia, spiritual traditions, homesteads, rituals, mission activity or cultures, such as the Zulu’s, Xhosa’s, Matabele, Malay, Indian etc., each with its own character, traditions, language etc.

During the post-Victorian era, some condescending picture postcards images were meant to pass as humour. They may have been of bare breasted women from rural areas playing table tennis, holding tennis rackets or a couple in a western embrace etc.

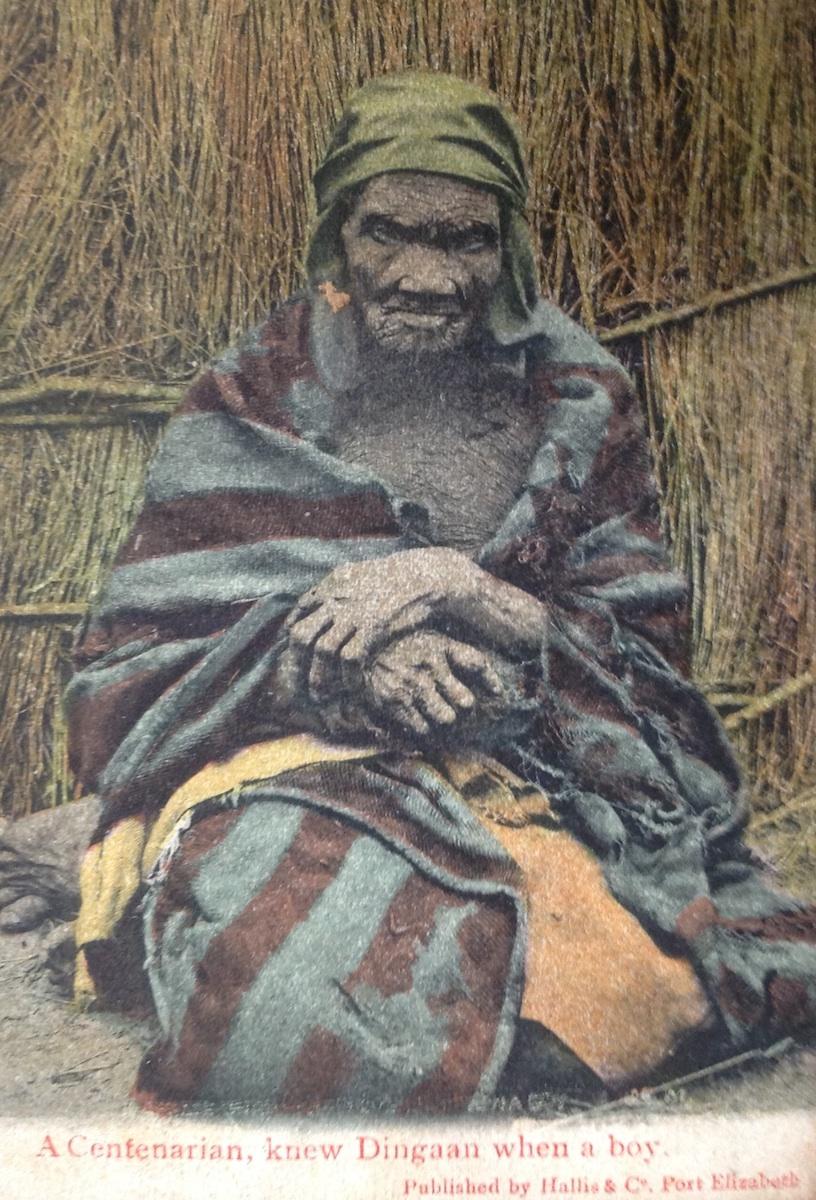

It can safely be assumed that the inscription on the card is correct. Dingaan was the Zulu King between 1828 and 1840. Card published by Hallis & Co – Circa 1905. Hand coloured card.

In South Africa today, it is essential that the cultures of its many people be recognised and safeguarded by museums and collectors, especially considering the current focus on capturing our countries Afrocentric history. Ongoing research and publication of such work remains crucial in terms of interpreting our own cultural history.

Brief history of South African Picture Postcards

South African picture postcards, published between 1896 and the late 1910s represent scenes frozen in time and in turn conjure up images of days gone by. These antique picture postcards, produced at the height of European colonialism, were send by Western travellers, business people, colonialists and traders.

Since their inceptions, picture postcards provided a leap into the world of wider communication, making people more aware of the world around them and allowing the ordinary man to buy cards that reflected his views/experiences, and if he so chose, enabled him to capture his own thoughts on the card.

The early picture postcard can be compared with the social media of today.

Communication, or social networking, took place via the postal system. People either wrote long letters posted in an envelope or wrote short, often cryptic messages, on the back of a postcard. These cryptic messages in themselves also provide us with a rich social historical context.

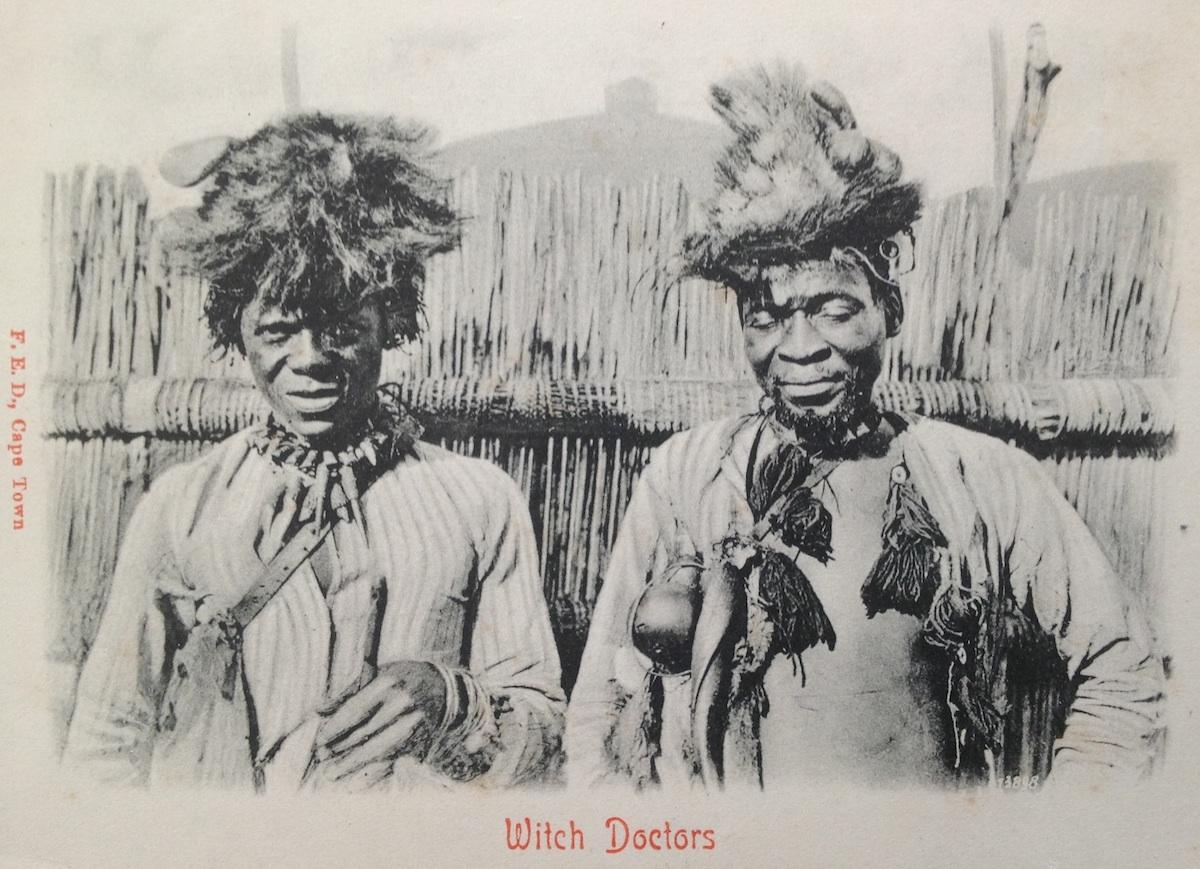

Witch doctors. Card published by Cape Town based F.E.D. Circa 1905

South African picture postcards produced between 1900 and mid 1910s can broadly be divided into four elementary categories, namely:

- Cards that contained no images, a photograph or any other form of art work;

- Cards produced locally or cards produced abroad;

- Early cards with undivided backs and later cards produced with divided backs;

- Hand coloured or black-and-white photographs.

Picture postcards have become highly collectable today. Many postcard collectors (referred to as deltiologists), collect and research many facets of early South African history, resulting in some fascinating and well researched collections.

The predecessor to the picture postcard was the postal stationary card of which many millions were mailed between 1885 and the late 1890s. First introduced in Europe during 1869 they achieved limited success in South Africa when introduced during 1877. These were postcards, without any images on them, provided for limited writing space.

Printing technology had been changing like any other industrial process. Picture postcards productions methods changed over time as new print technology became available. Three-colour printing and the photographic techniques used in process work, enabled pictures to be produced with the rotary process. Soon postcards were churned out in large numbers.

It has been suggested that the firm of Booleman & Epstein produced South Africa’s first picture postcard in the then Transvaal, with the Jameson raid during 1896 as the theme. The Cape followed suite the next year.

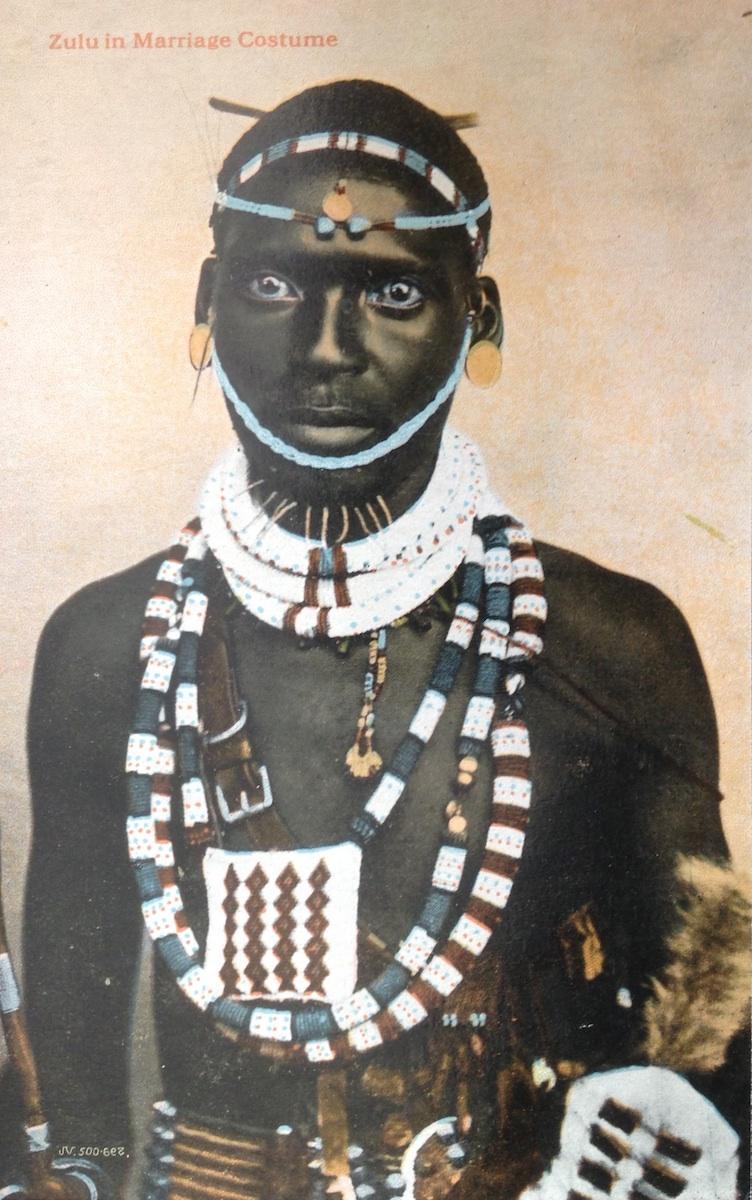

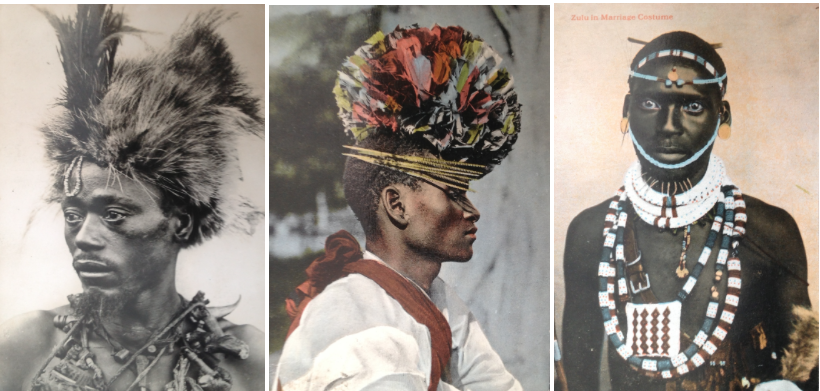

A Zulu male in traditional wedding attire. Card published by Valentine & Sons (Cape Town). Circa 1912.

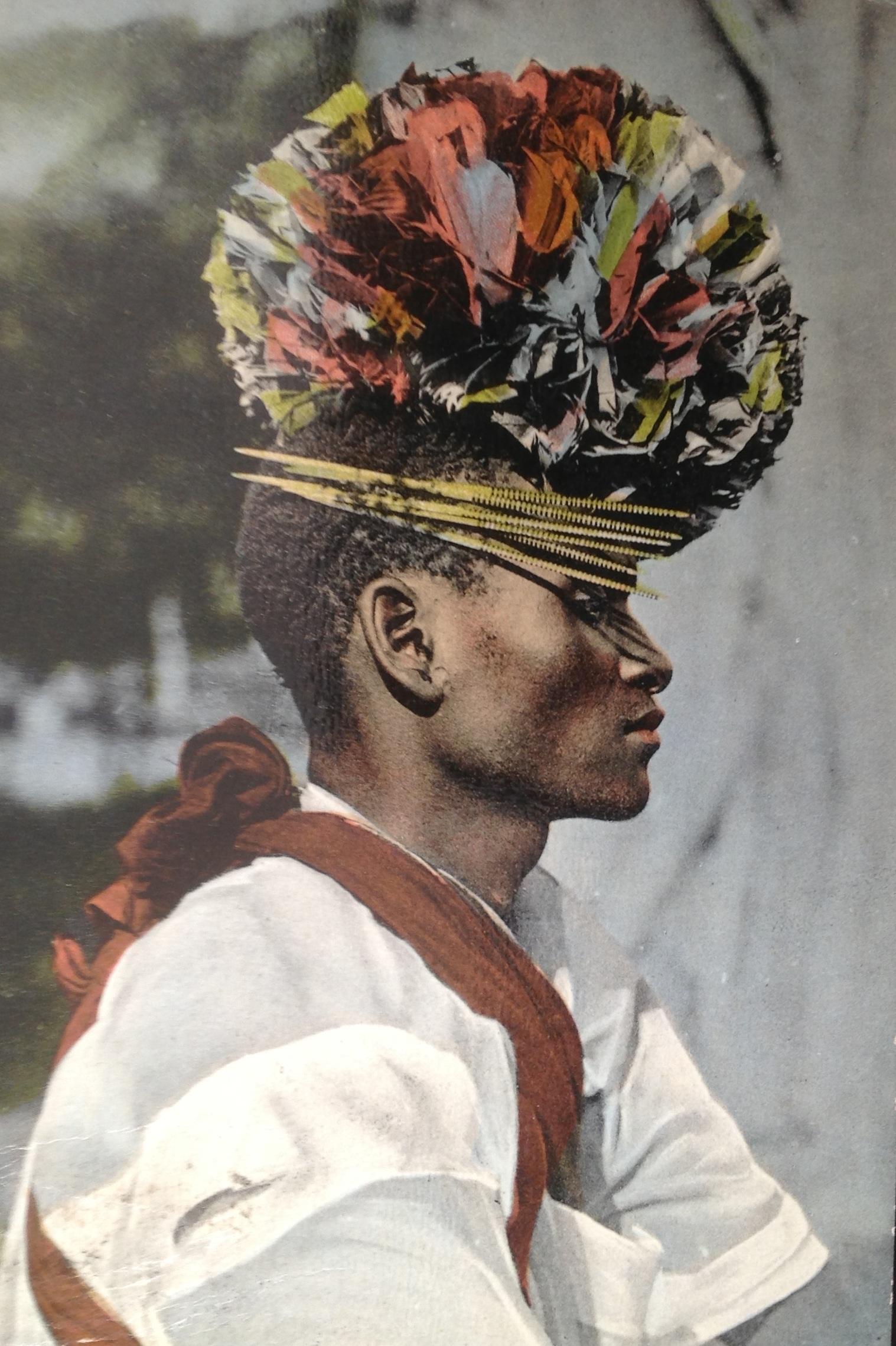

A Rickshaw with elaborate headdress. Card published by Hallis & Co (Port Elizabeth). Inscription on the back reads: “Photograph supplied by publicity department South African railways”.

Postcards, together with the mass-produced stereo cards, made people more aware of the world around them – it stimulated visual fascination.

This resulted in everyone being able to choose and buy cards with a multitude of photographic or artistic themes and topics. Correspondence by post was affordable and accessible to most people and hence the postcard was used to pass messages from one suburb to the next, one town to the other or one country to the next.

Today, many of the messages make for intriguing reading, contributing to a better understanding of social interaction at the time, especially also in times of crisis.

Messages were often as elementary as “Greetings”, “with love” or “arriving at station on Tuesday at ten”.

A series of events in South African history from the late 19th century onwards, such as diamond and gold finds or the Anglo-Boer war, resulted in an influx of photographers and artists who recorded these events. Photographers for postcard publishing companies were either professionals or semi-professionals. The irony is that no photographer, producing photographs for these companies, ever really became famous for applying their profession.

Picture postcard publishers also frequently regarded the photograph as a mere raw material for the final picture postcard. Something different was often created from the original photograph by means of retouching, colouring or combining several pictures into a montage.

Atkinson, as per Norwich (1986), determined that South Africa had 357 publishers whilst 72 overseas publishers published cards with South Africa related themes between 1896 and 1914. European publishers from England, Germany, Belgium, Holland and France were especially active during the Anglo-boer war.

Well known publishers were Sallo Epstein, Hallis & Co, Braune & Levy, R.O. Fusslein and SAPSCO. The latter produced Real Picture postcards. These were actual photographs published as postcards (click here to read the author’s previous article on Real Picture postcards – Place link here).

A Matabele male showing interesting costume jewelry. Card printed in England. Circa 1908

The variety of cards published in South Africa was not as diverse as those published in Europe or America. South African publishers for example, seldom produced cards depicting musicians, popular actors, glamour or even nudes.

“Postcarding”, as a means of communication, dissipated due to the wider use of the telephone and the increase in the postal rates during 1918.

Picture postcards of this era fortunately still surface on a regular basis as modern families rid themselves of documentary family history they cannot relate to or have no sentimental attachment to.

Most cards published in South Africa ended up in Europe. Europe, until today, remains a primary source for South African collectors to repatriate such cards.

Produced by companies or individuals, the subject matter that was presented on these cards was limitless. By far the most popular cards were topographical cards. These cards featured South African towns, with street scenes showing public buildings such as town halls, post offices, churches, hotels, schools, banks, railway stations, bridges market places, mission activity etc. Patriotic or propaganda cards were also very popular during times of conflict such as during the Anglo-Boer war.

Picture postcards of old have largely made way for modern cards in the form of Valentine cards, Mother’s Day cards and many variety of birthday cards. Until recently travellers would also often bring home modern picture postcards to show family and friend exotic destinations they had travelled to, but today images taken on cell phones have replaced the printed postcards. Who knows, maybe these modern cards will become highly sought-after collectors’ items in 100 years’ time.

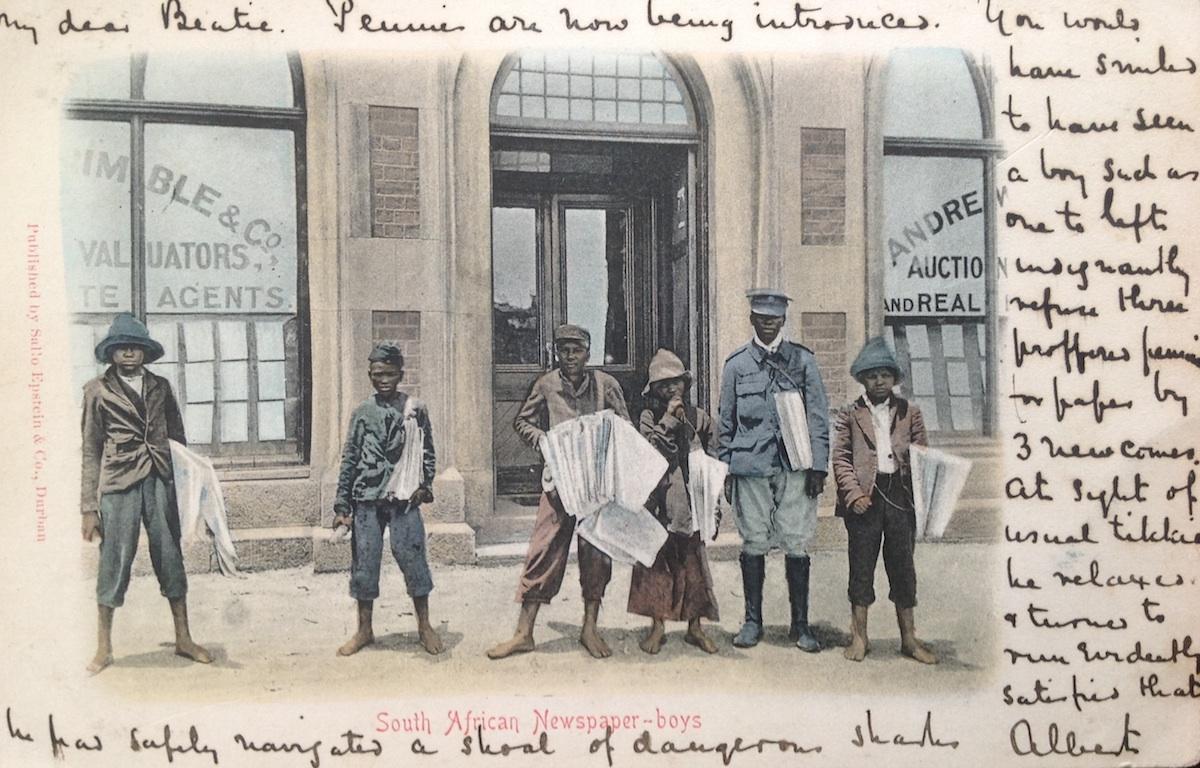

Young newspaper sellers in Johannesburg. Card published by Sallo Epstein. The handwritten note on the front of the card makes reference to new pennies that have just been introduced. Circa 1908.

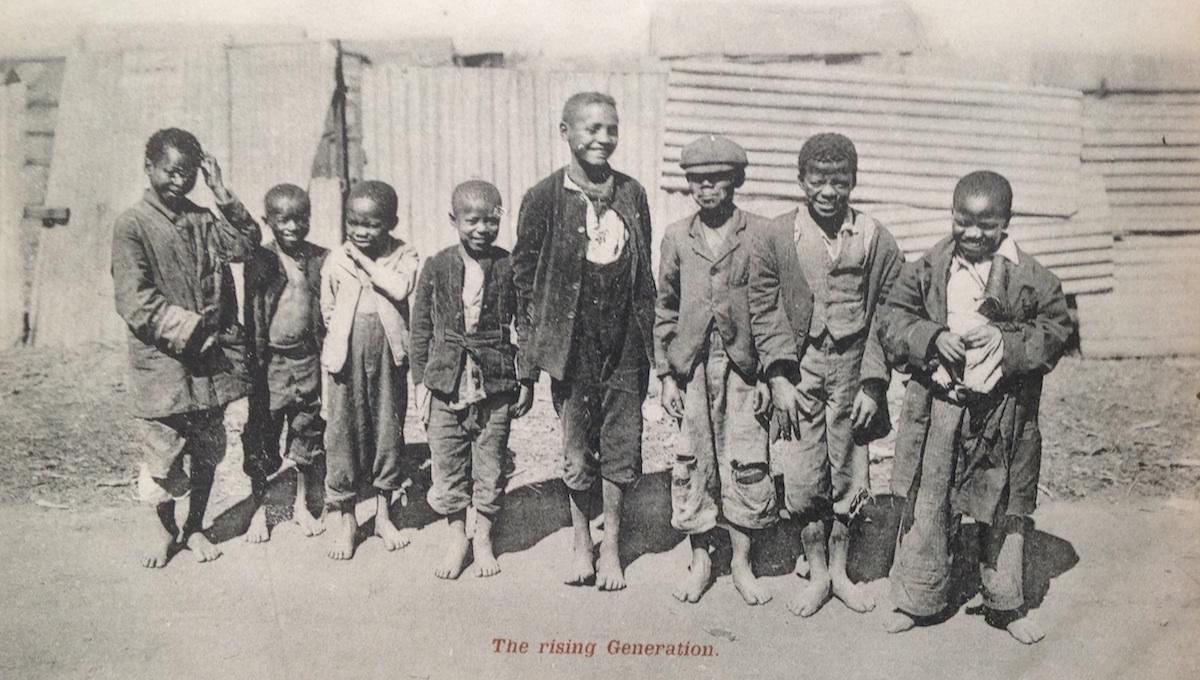

The rising generation. Card published by Hallis and Co (Port Elizabeth). Circa 1907

Following the European trend, a few South African books have been published making use of these picture postcards to portray a glimpse of days gone by, depicting town scenes of for example Johannesburg, Durban, Kimberley and Simonstown. The author understands that a book, with a limited print number, has been privately produced on Pretoria as well.

The heyday of the postcard as a cheap way for the public to correspond, has come and gone but we are left with an incredible valuable legacy for which we should be grateful to our forefathers.

Would today’s modern way of communicating and messaging via the various social media platforms still be accessible some 100 years from now? - Highly unlikely. This confirms the immense value in the historical images and messages on these antique picture postcards.

During 2016, the author exhibited a collection at a national level on Namibian Ethno-photographs in postcard format for which he was awarded the highest accolade.

The postcards presented in this article are an extract of some 160 ethno-photographic postcards that will be exhibited by the author at a national exhibition during October 2018.

About the author: Carol is passionate about South African Photographica – anything and everything to do with the history of photography. He not only collects anything relating to photography, but also extensively conducts research in this field. He has published a variety of articles on this topic and assisted a publisher and fellow researchers in the field. Of particular interest to Carol are historical South African photographs. He is conducting research on South African based photographers from before 1910. He is also in the process of cataloguing Boer War stereo images produced by a variety of publishers. Carol has one of the largest private photographic collections in South Africa.

Sources:

- Atkinson, A. (2007). Something of a novelty – Postcards of South Africa. S.A. Manx Association

- Beukers, A. (2007). Exotic postcards – The lure of distant lands. Thames & Hudson. New York

- Coan, S. (11 August 2018). Email communication confirming name of Zulu chief Ngcolosi.

- Corrigall, M. (25 July 2018). Email communication on his research on the photographer Minna Keene. University of Johannesburg.

- Frescura, F. & Maude-Stone, B. (2013). Durban – Once upon a time. Archetype Press. Durban

- Hardijzer, C.H. (2008). Old postcards tell their story. Village Life No 29

- Hardijzer, C.H. (2018). Images included in article form part of the Hardijzer Photographic Research Collection.

- Kumagai, Sare (internet extraction 18 July 2018). Bias and positivism – The dilemma of Ethno-photography (www.sarekumagai.com)

- MacDonald, I (1990). The Boer war in postcards. Bok Boeke International. Durban

- Norwich, O.I. (1986). A Johannesburg Album – Historical postcards. AD Donker. Craighall

- Oliver, R. S. (2012). Reflections on Southern Africa – A postcard collection. Africana library. Kimberley

- Oliver, R.S. (1997). Images of Kimberley – A postcard collection. Africana library. Kimberley

- Stevenson, M & Graham-Stewart, M. (2001). Surviving the lens – Photographic studies of south and east African people, 1870 – 1920. Fernwood Press. Vlaeberg

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.