Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

The zenith of long distance passenger travel by train world wide was during the period between the two World Wars (1919 to 1939) thereafter there was increasing competition from other modes of transport, notably the airliner and the motor vehicle (utilising modern road infrastructure), which led to a rapid decline in patronage for rail travel. At the ending of the Second World War (1945) there was a large surplus of Douglas Dakota twin engine aircraft that were sold off at bargain prices, this effectively kick started the modern airline industry.

One hundred years ago aviation had literally only just got off the ground and was at an early stage of development and road infrastructure was poor and not fit for long distance travel, thus the railway was the main carrier of freight and passengers.

The discovery of gold along the Witwatersrand (the “Rand”) in 1886 completely eclipsed Kimberley and the boom town beside the diggings, to be called Johannesburg became the driving force behind the South African economy, even before political union in 1910. The old saying “All Roads lead to Rome” could well be corrupted to “All Railways lead to the Rand” such was Johannesburg’s importance (click here for more details). Its geographic position on the Highveld, far inland meant that transport corridors from the coastal ports were quickly implemented, the most important being the main railway line coming up from Cape Town. The Cape Government Railways (CGR) had already pursued a policy of building railways towards the interior from the three major ports of Cape Town, Port Elizabeth (PE) and East London with the lines converging on a junction at a farm called De Aar, in the middle of the semi arid Karoo, known for its ample water supplies. De Aar was reached by 1884 and the rail link between Cape Town and PE was made, however that was not the final goal as the line was continued onward to Kimberley, which became a railhead 625 miles from Cape Town in 1885.

The political disagreements between the governments of the Cape Colony and the Transvaal Republic (read Cecil Rhodes and Paul Kruger) meant that an extension of the line from Kimberley to Johannesburg via Klerksdorp was not possible, therefore a less direct route was devised with the co-operation of the Orange Free State (OFS) whereby the line from PE to De Aar had a junction placed at Noupoort in order to project a new line (wholly financed and built by the CGR), that would cross the Orange River at Noval’s Pont and thence go onwards to Springfontein, Bloemfontein and Viljoensdrif on the south bank of Vaal River. The Transvaal government finally agreed to build a line southwards from the Rand to meet the CGR at the Vaal and a temporary bridge was placed across the river to allow the first train from Cape Town to cross to arrive at Park Station, Johannesburg on the 15th September 1892.

Cape Town was the first port of call for the ocean liners that sailed to and from Europe and although it was the furthest port away from the Rand the sea voyage was shorter than having to sail further round the Cape to reach the other ports. Even before the turn of the 20th Century advertisements by the Union or Castle Lines were offering journeys from Southampton to the Goldfields, taking 19 days - 17 days by boat and 2 days by train. When a ship berthed in the Cape Town harbour, there waiting at the pier was a train ready to speed the passengers on to Johannesburg. It was said “The transference from ship to train was as intimate as with a Channel packet steamer on the Admiralty Pier at Dover”.

Competition for the lucrative trade with Johannesburg came from the other ports around the Cape coast, namely (going anti-clockwise) Port Elizabeth, East London, Durban and Delagoa Bay (Maputo). Delagoa Bay was the nearest port to the Rand but was not developed to the extent of the other ports, primarily because it was in a Portuguese held territory. Durban however was in Natal and competition was fierce between the two British colonies of the Cape and Natal to the extent that at the height of the railway building mania into the interior (1888-1894) the Cape Colony had forged an alliance with the Orange Free State and Natal one with the Transvaal.

The early history of our railways (from 1860) hardly suggests anything in the way of luxury travel as it was generally the case of providing a means of basic transportation superior to the ox-wagon rather than fast comfortable trains, however a watershed was to occur shortly after the Second Anglo Boer War, when Britain had consolidated control of all four colonies. The Imperial Military Railways had given way to the Central South African Railways (CSAR) which ran the railway services of the Transvaal and the Orange River Colony until 1910. In 1903 the CSAR took delivery of some magnificent wooden bodied (mahogany panelled) bogie coaches, built in Britain by the Metropolitan Amalgamated Carriage Wagon Co. that were the most luxurious to be found anywhere in the world at that time. A premier through service between Pretoria and Cape Town was inaugurated with these coaches to serve the high end of the travel market.

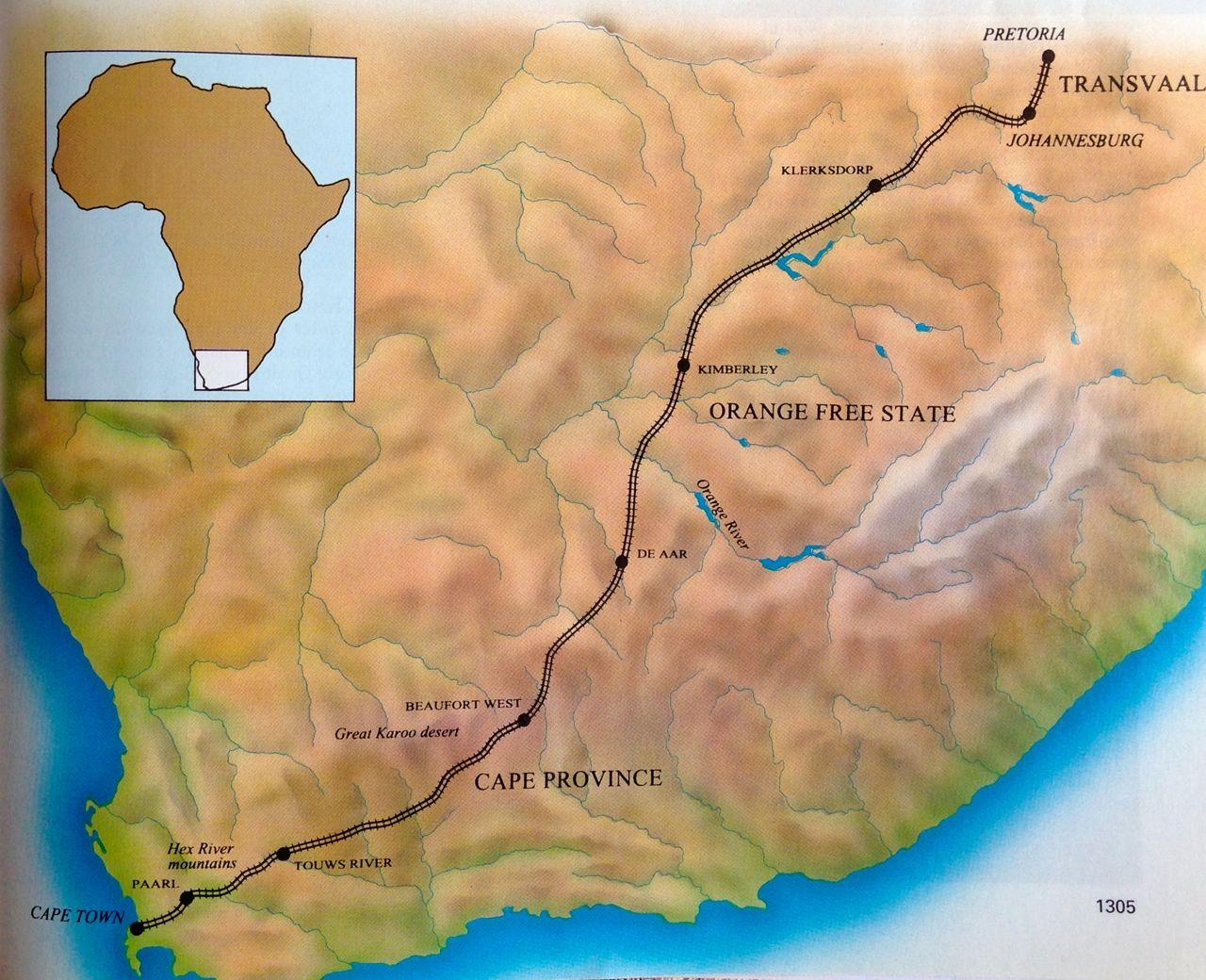

By 1906 the CSAR had connected with the Cape Government Railways (CGR) at the junction at Fourteen Streams (on the Vaal River), allowing trains to be finally run through via Klerksdorp instead of the more circuitous route via Bloemfontein. The “Down Run” from Pretoria was worked as far as Kimberley by steam locomotives of the CSAR after which steam locomotives of the CGR hauled the train onward to Cape Town. The distance between Pretoria and Cape Town is roughly 1 000 miles (1 609 km) and locomotive and crew changes were made at intermediate stations along the route, namely Klerksdorp, De Aar, Beaufort West and Touws River. The “Up Run” from Cape Town was handled in a similar fashion. The scheduled timings of the train were leisurely by comparison with European railways and in 1910, when the South African Railways (SAR) were formed (at the time of the Union), the “Down Run” would take 44 hours. The “Up Run” was always a slower affair by an hour or so, as Johannesburg (highest point) was 5 750 feet (1 753 m) above sea level and the engines had to slog up the gradient.

Rail Route from Cape Town to Pretoria (The World of Trains)

Not to be outdone the Natal Government Railways (NGR) in addition to it normal services commenced running a luxury corridor train between Durban and Johannesburg, advertised as “the most Direct Interesting Route to the Goldfields”, however to the many thousands of people flocking to the Rand from overseas the Cape Town to Johannesburg route was still preferred as less time was spent at sea.

Advertisement for Natal Government Railways shortly after opening of the rail link to Johannesburg (Transnet Museum via The Natal Main Line Story)

As time passed newer and more powerful steam locomotives were introduced and the timings between the Rand and the Cape were reduced so that by 1923, when the “Union Limited” was introduced, to coincide with the sailing of the Union Castle Liners the scheduled time for the trip from Johannesburg to Cape Town (“Down”) was advertised as 29 hours 21 minutes whereas the “Up” was 30 hours. An interesting quirk was that the “Up” was distinguished by being called the “Union Express”.

The Union Express leaving Cape Town (Railways of Southern Africa by OS Nock)

The “Union” trains were First Class only and although they ran with varnished wooden bodied coaches they were the forerunners of the world famous “Blue Train”. It was the addition of a new dining car named “Protea” in 1933, which had its sides painted in blue and cream and its roof silver, that would set the trend and by 1936 all the carriages had been painted to match. People standing on station platforms would oft say “there goes that Blue Train” as it passed through and that became the train’s nickname.

In 1937 an order was placed with Metro-Cammell of Birmingham, England for twelve luxury, air conditioned sleeping coaches of all steel construction, which was later supplemented with two dining cars, two kitchen cars and a baggage van. Delivery was completed by 1940 and the train ran until 1942 as a troop train, thereafter it was put into storage until the end of the Second World War. The nickname of “Blue Train” that had been given to the “Union” trains pre-war was officially recognised by South African Railways (SAR) and the Blue Train was inaugurated in 1946 by the then Minister of Transport, F.C. Sturrock.

Popular Books on the Blue Train

This set of coaches ran until 1972 when it was replaced by an even more luxurious set built locally by the Union Carriage Wagon Co. of Nigel; a true five star hotel on wheels costing the staggering amount of R4.5 million. The old set was not discarded and was refurbished and repainted light green and continued in service as the “Drakensberg Express”, between Johannesburg and Durban until 1985.

It may be thought of as strange that there was a requirement for a new luxury train at a time when jet air travel was shrinking the world and an overnight flight from London to Johannesburg took less time than a train journey from Cape Town to Johannesburg and therefore was there any longer a need for such a train? The answer was that the Blue Train ceased to be a means of getting from A to B in style but became a tourist destination in itself. This being so it no longer mattered where the start and finish of the journey was and new routes were advertised to attract tourism to South Africa. To augment the traditional route of Pretoria to Cape Town, new routes from Pretoria to the Victoria Falls and Pretoria to Hoedspruit (for the Kruger Park) were offered.

Blue Train moving across Victoria Falls Bridge (The Blue Train by Gus Silber)

The haulage of the Blue Train is either by electric or diesel traction, steam having been phased out by the early 1980’s. On the traditional route the Blue Train is usually pulled by two electric locomotives between Pretoria and Kimberley, energised by the 3 kV DC system. From Kimberley to De Aar it is hauled by two diesel-electric locos, which are then switched for two electric locos powered on the 25 kV AC system which take the train onto Beaufort West where there is a final change over back to the 3 kV DC system to take the train to Cape Town. One locomotive has the necessary power to propel the train but two locomotives (sometimes three) are used as a precaution against a break down.

While the “Blue Train” has always been considered the most luxurious train in South Africa there is another train that has vied for the title and that is the “Pride of Africa” run by the private concern - Rovos Rail. Both trains are opulent and offer similar itineraries; a case of “you pays your money and takes your choice”. Whereas the “Blue Train” has a reputation of long standing, the “Pride of Africa” has only been operating since 1989 and is the vision of one man, Rohan Vos (hence Rovos) a train enthusiast who had the resources to make a hobby into a business. He was able to take over the Capital Park steam locomotive sheds in Pretoria, which became his base for operations. Steam engines were at first a major part of the Rovos Rail programme, with the restoration of three SAR class 19D “light” 4-8-2 tender engines, however steam mileage has dwindled dramatically as the infrastructure needed to support the locomotives has deteriorated or has been removed, thus Transnet diesel and electric locos do most of the hauling. The most exclusive service to be offered by Rovos Rail is the once a year trip from Cape Town to Dar es Salaam, which takes 12 nights to complete. It is the nearest thing to a Cape to Cairo experience that one can get.

This article only scrapes the surface of what is a fascinating part of South African history, should the reader wish to delve more into the topic kindly refer to the list of further reading below.

Post Script Johannesburg took the place of Cape Town as South Africa’s main port of entry when Jan Smuts Airport (now O.R. Tambo) became the hub of the sub-continent for air travel.

References and Further Reading

- “Railways of Southern Africa” by O.S. Nock, first published 1971 by A C Black.

- “The Blue Train” by David Robbins, first published 1993 by VIKING.

- “The Blue Train” by Gus Silber, first published 1999 by David Barritt & Co.

- “This is SAR & H RAILWAYS Handbook 1978, A Thomson Publication.

- “The World of Trains” Part 65, “Great Journeys - The Blue Train”, 1993.

- “A Guide to TRAINS, the World’s Greatest Trains, Tracks & Travel” edited by David Jackson, first published 2002 by Fog City Press.

- “Great Railway Journeys of the World” Part 2 “South Africa - Zambesi Express” by Michael Woods, first published 1981 by the BBC.

- The Blue Train website: www.bluetrain.co.za

- Rovos Rail website: www.rovosrail.co.za

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.