Review of Charles van Onselen's The Night Trains. Published by Jonathan Ball Publishers in 2019.

Charles van Onselen is the well-known successful social historian of Southern Africa. He has notched up several important books (The Seed is Mine, The Fox and the Flies, Cowboy Capitalist, Masked Raiders) that take pride of place in an essential Africana collection. His writing is never dull and he breaks the academic barriers to craft a superbly-researched account with style and verve. He writes with passion and burning white anger. His work transcends the more traditional approach to writing history. With van Onselen you know who the victims and villains are; he draws on the historical evidence rather like a musician, to orchestrate the story he wants to tell. He is not afraid to look at cause and effect and human agency and agony.

He probes the complexities of that mix of mining, technology and men embroiled in a herculean effort to either get rich or even just to scratch a living in a capitalist system. It was and still is a system stacked against the poor rural, underdog. This book is about the migrant workers who were recruited to become miners on the Witwatersrand; they worked on the terms and conditions set by the mining capitalists at wages determined by a complex interplay of the international price of gold and the local circumstances. A key function of the Chamber of Mines came to be that of centralizing labour recruitment of migrant workers, turning the Chamber of Mines into a monopsonistic purchaser of labour. The Chamber of Mines no longer exists as it has changed its name to the Minerals Council, but it was at the core of the success of the group corporate system of the gold mining industry. White mineworkers organized early and used tactics such as the racial colour bar and the closed shop to promote their interests and to challenge the mine owners in the great strikes of 1913 and 1922. But prior to the rise of the National Union of Mineworkers, black capacity to bargain through collective action was sporadic and limited; migrant labourers had little power to organize and strike.

Chamber of Mines Building in the Johannesburg CBD (The Heritage Portal)

The Witwatersrand Native Labour Association (WNLA), formed in 1902, recruited labour in Mozambique and so came to run trains to the Witwatersrand. Van Onselen is brilliant in combing the primary research records of the WNLA (later part of TEBA – The Employment Bureau of Africa) and has mastered all of the secondary literature.

Here is a fascinating story about the coming of the railway to Southern Africa and its impact on the potential for economic development and on the men of Mozambique who became the migrant labourers on the gold mines of the Witwatersrand. But before one gets to the story of the mass movement of people one has to take a step back into railway history and why steam locomotives and trains mattered.

Railways brought speed, quickened the pace of economic possibilities; drove investment, were the means of transporting people and goods. Millions of people could migrate across oceans in steam ships and then climb into carriages at railway stations and anticipate reasonably comfortable and safe transcontinental journeys by rail to fulfil manifest destinies. Railways conquered distance whether in Europe, North America, India or Africa. Railways were at the heart of the second industrial revolution during the first half of the 19th century and all countries wanting to advance their economies into modernity and permanent economic growth had the railway and the steam locomotive at the vanguard of progress. Railway lines, those parallel iron tracks cutting across continents, became the essential infrastructure for steam powered locomotives drawing carriages coaches and cargo trucks. Rails were the vehicles of progress in Africa for nearly a century. It was Rhodes’ dream for the British to open up the path of conquest into “darkest Africa” with a Cape to Cairo line.

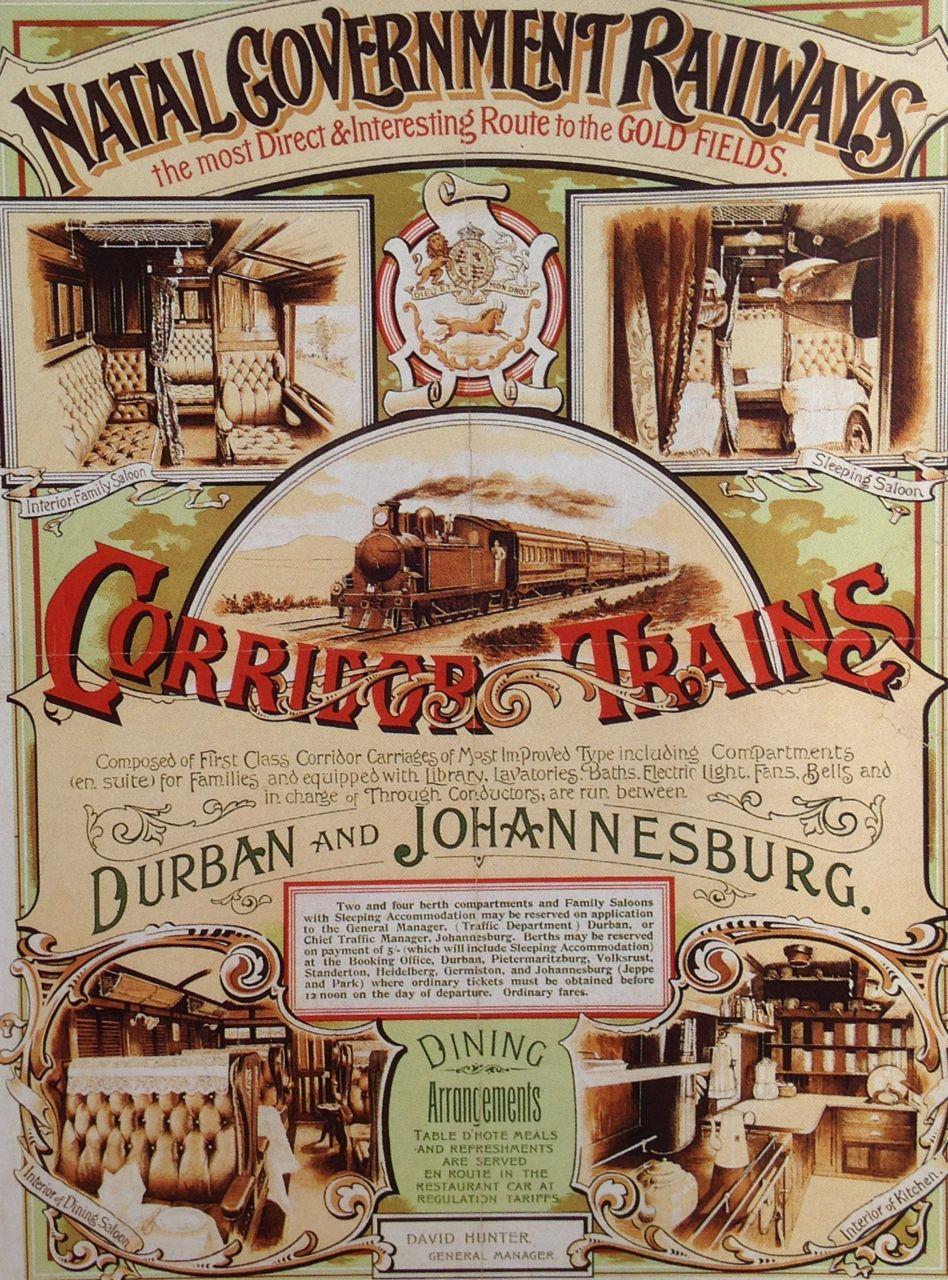

South Africa was relatively late in finding the capital to pay for railways and it was the discovery of diamonds in Kimberley that then determined the routes for the laying of those iron tracks. The focus was from the coastal ports inland to the Northern Cape from Cape Town, Port Elizabeth and East London. Then, when gold was the next bonanza, the railway lines extended north to the Transvaal, to Pretoria and Johannesburg and from Lourenço Marques to the then Zuid Afrikaanse Republic. As was the case elsewhere, the choice between state ownership and private company enterprise was keenly debated. Construction of a railway was expensive and risky and the volume of traffic from sparsely settled communities and rural produce was unlikely to lead to appealing profits, so that even where railway companies were floated government underwriting an acceptable return was both desirable and necessary. In Kruger’s Republic the NZASM or the Nederlandsche Zuid-Afrikaansche Spoorweg-Maatschappij was a private company established for profit whereas in the Cape and Natal, railways were run by government - in these facts there were huge complexities of logistics, economics, profits and politics. To get the most out of this book a prior grasp of how railways developed in disparate ways across the sub-continent is an advantage.

An old advert for the Natal Government Railways (Transnet Museum)

South Africa was unusual in that industrialization started with a mining revolution; industrial development was shaped by the mining sector – the needs of gold, coal and iron ore. Agriculture lagged way behind and an agricultural revolution which in other countries preceded industrial development only followed after World War II. Meanwhile mining and industry needed labourers drawn from traditional agricultural worlds which meant migrant labour and temporary sojourns on the mines and in the cities created an entirely different type of development trajectory. The migrant labourers retained their ethnic and tribal roots; families were fractured as the men came to work on the mines for short term contracts and men lived in monastic hostels. It was an unnatural life and sowed seeds for social dislocation. Today we are still left with that legacy of urban hostels where periodic violence spills out in erupting pressure points. This is the tragedy of our skewed economic development.

Van Onselen zooms in on the microcosm of history – a single railway line for a specific purpose in a defined period of time. Before you think The Night Trains has to be a railway romance, let me disabuse you. It is a moving story of people caught in a system, and a world defined by crude racism, unjust laws, attitudes of colonial superiority and inhumanity. The men of Mozambique were simply a factor of production in the equation of labour, capital and minerals.

Book Cover

The Randlords of the Witwatersrand were the immigrant capitalists who sourced the capital, formed companies, employed geologists and sponsored the technology to mine in totally new ways on the Witwatersrand. They needed that combination of capital, knowledge, skilled miners but also unskilled miners by the hundreds of thousands - brawny, healthy men with the physical attributes to work at high temperatures, in humid, stifling underground cramped stopes. Geological knowledge plus skilled international mining technology created a maze of tunnels two miles below the earth to enable teams of men to work underground and extract that gold bearing ore. Dynamite was laid to blast the pyritic low grade reefs. Deep level mining presented unique challenges. Smart technology used chemistry and science to crush, pulverize the rock and extract those golden specs from the ore. Payable gold was the objective when the price of gold under the gold standard was set by the international central bankers.

Gold underpinned the international monetary system that evolved from the 18th century until the 1970s, gold was needed to support currencies and expand the money supply in the major western economies. Being on the gold standard with a fixed price and stable price for gold meant that the economic fundamentals of supply and demand did not apply. Profitability in gold mining depended on producing more gold, noting that there was no limit to the amount of gold that could be sent to London or Fort Knox, but costs had to be contained and could never exceed the magical fixed price of an ounce of gold. The history of gold mining has to start with that peculiar almost illogical combination of sophisticated technology, international finance and raw muscle power. This was why a labyrinthine network of labour recruitment spread through Africa to bring men from remote rural areas thousands of miles away to Johannesburg at the centre of the Witwatersrand gold mining industry.

The author tells the human story of the men of Portuguese East Africa from places like Sul de Save who came on the Eastern main train line to Johannesburg to be exploited, badly treated, discarded and sent back to their homes often in broken health and suffering from miners phthisis at the end of their contracts. They were the migrants and victims of skewed industrialization.

Van Onselen concentrates on the years after the Anglo Boer War, post 1902, when the mining capitalists faced the challenge of finding low cost labourers equipped with rock hammers and drills to attack the pyritic ore deep underground on the Witwatersrand to release the gold bearing ores. Gold mining on the Witwatersrand was capital, technology and labour intensive. To start the mines after the Anglo Boer War, the importation of Chinese labour was attempted but ran into political headwinds and was cut short. Cheap manual labour had to be sourced locally, on the African continent. Mozambique, in the hands of the Portuguese was one of the territories that offered a ready large pool of cheap labour.

Old postcard of Chinese Miners

Between 1910 and 1960 some 5 million passengers were moved by train from the Komatiepoort / Ressano Garcia station on the Mozambique South African border to the Booysens Station in Johannesburg and then allocated to mines to then live in single sex mine compounds. It is a story worth telling and one that made me weep when learning about how men, whether well or ill were treated like cattle and cargo on that railway journey, in slow moving trains over that distance of several hundred miles.

Van Onselen, uses his insight and research to tell the story of the Mozambican people of the Sul do Save and their extraordinary journeys from the Indian Ocean coast and the low veld to the plateau and the Highveld and what those journeys meant as rural preindustrial men were transformed into miners in this stark industrial underground world. The climactic moment in the book was the so-called train accident on that fateful day in 1949 at Waterval Boven in the Eastern Transvaal (today’s Emgwenya). Van Onselen considers that this was no accident but was the consequence of a brutal labour and economic system. In this he is spot on. So often when one probes an accident in an inquest, cause and consequence are seldom acts of God.

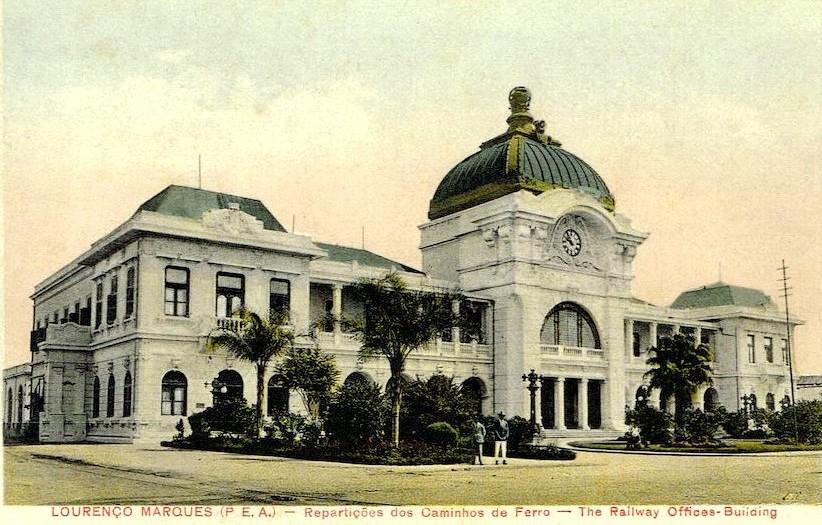

Johannesburg acquired the superb Leith and Moerdyk designed station of the 1920s with its gateway to Eloff Street while Lorenco Marques has its grand railway station opening on to the grand Portuguese plaza. Look beyond those grand edifices and ask questions about what really drove the economies of South Africa and Mocambique.

The Leith and Moerdyk designed station

Old Postcard of the Maputo Train Station circa 1920 (Wikipedia)

Van Onselen is dismissive of people interested in the heritage legacy of buildings and the visible remnants of the survivals of those railway lines; or what can be seen of the engineering feats of cuttings, bridges and shaped stones. He is sharp in his criticism that heritage-peddlers are too often lackeys of nationalist politicians and too readily look at the site of a single disaster (such as that 1949 train disaster at Waterval Boven) to weep crocodile tears and think they have found history.

Charles van Onselen (National Research Foundation)

Point taken, but I disagree with Van Onselen because heritage, if used with intelligence and insight, can be the tool to access the more complex history - the very history Van Onselen explores. History and heritage are not interchangeable. I agree nostalgia and railway romance should not drive the narrative but artefacts and objects, such as a locomotive or a railway tunnel are the survivals which can then trigger a deeper look at social history.

Van Onselen’s is a powerful voice in speaking for the migrant men of Mozambique who made gold mining on the Witwatersrand possible and who paid a high price.

Kathy Munro is an Honorary Associate Professor in the School of Architecture and Planning at the University of the Witwatersrand. She enjoyed a long career as an academic and in management at Wits University. She trained as an economic historian. She is an enthusiastic book person and has built her own somewhat eclectic book collection over 40 years. Her interests cover Africana, Johannesburg history, history, art history, travel, business and banking histories. She researches and writes on historical architecture and heritage matters. She is a member of the Board of the Johannesburg Heritage Foundation and is a docent at the Wits Arts Museum. She is currently working on a couple of projects on Johannesburg architects and is researching South African architects, war cemeteries and memorials. Kathy is a member of the online book community the Library thing and recommends this cataloging website and worldwide network as a book lover's haven.