In its heyday in the 1970s and 1980s, Ravan Press was regarded as the daring, oppositional anti-apartheid publisher in Johannesburg, ready to take an alternative perspective of South African society. The publishing firm was established by Peter Randall, Danie Van Zyl and Beyers Naude and the firm's name, Ravan was an amalgam of their three names. They were publishers of the left and they supported the academic struggle for a different view and ideological interpretation of social issues of the day. Ravan would publish what other publishers thought unviable or too risky. This was a publishing story of courage and great achievement during difficult decades.

At the University of the Witwatersrand, the History Workshop, founded in 1978, emerged as an institutional presence to encourage and give substance to new forms of history and most particularly to give an authoritative voice to the working classes. This was to be social history from below. There was a ferment of activity as workshops, seminars, papers and publications appeared. It was an exciting time to be a student or a young lecturer to realize that history could be a tool for social justice and political change.

This book is a product of the link between Ravan Press and the Wits History Workshop. It was yet another publication to commemorate the centenary of Johannesburg in 1986, though strangely the date for Ferreira's camp (called here Ferreira's town) making its appearance in Johannesburg is dated 1885-6, but the sketchmap positioning Ferreira's camp was the first known map of Johannesburg and was 1886. A reproduction was included in Anna Smith's Pictorial History of Johannesburg as a prized insert. I suppose the argument can be made that the Struben brothers were prospecting in what is today Roodepoort as early as 1884 but their claim to being the Johannesburg founding fathers was dismissed long ago. Before I get into details let me make a few general points.

Pearson and Kallaway set out to produce a book of pictures of the early years of Johannesburg as a modest tribute to the early photographers of the town. Although they have gathered and set out well over 300 photographs, all in black and white and drawn from a variety of early newspapers, supplements, magazines, archives and Johannesburg Public Library collections, they have not researched who the photographers were.

The authors were not interested in the buildings, architecture and edifices of Johannesburg but turned the spotlight on working people in groups, at work, at leisure in street scenes and at political gatherings. There can be no sharper contrast in the use of the image than in setting the Kallaway and Pearson book alongside the Norwich, Johannesburg post card book (click here to read this review). The two books give very different perspectives of history and show precisely how the captured camera image or a newspaper sketch can tell very different stories through selection, the juxtaposing of images and interpretation. In that sense the two books together give a more comprehensive and realistic understanding of what life was like in Johannesburg in circa 1905 than each does on its own.

The objective of the authors in this book is to self-consciously pose the central question as to how to read a picture for its ideological content. They see a picture as an ideological or political statement and their book attempts to be a guide to ways of seeing. Collectively the selection of images itself becomes a source of evidence and interpretation of the past. These are images that try to answer the question as to the kind of society forged in the first fifty years of Southern Africa's industrial revolution. But because the focus is on working class life and working class people, the answer to their question is partial and incomplete. The argument would be far more convincing if the reader was left to draw her own conclusions about this new mining society, economy and community on the highveld. The divisions of that society along class, economic, race and gender lines is evident but what is missed is the fluidity of social mobility through gold mining wealth and accumulation. There is another missing story of entrepreneurship, risk taking, organizational skills and luck, all vital factors in the forging of the city of Johannesburg.

I have no quibble with the authors deciding to focus on the visual images and restrict their text, but then there is a duty to the reader to label and date photographs correctly, and to sequence these images in a date order. Many of the photographs have no other source reference other than JPL, i.e. extracted from somewhere in the Johannesburg Public Library (e.g. illustration 155 , "Indian brushmakers") and with no date, time or place, the image becomes meaningless for the reader. A photograph of "Johannesburg native township", also sourced from JPL, is similarly and hopelessly unhelpful. There are more than a dozen illustrations without labels at all. I would love to know what was behind the selection of say, illustrations 118 to 124 (not labeled).

Indian Brushmakers

Like the Norwich book there is also a separate chapter on the Chinese Labour experiment of the post Boer war period which lasted from 1903 to 1910 (when the last of the Chinese labourers left the Rand). Norwich provides a better account of the background and his postcards are well chosen. Pearson and Kallaway have more photographs, with a particularly vivid one of the roll call of the Chinese miners at Simmer and Jack (circa 1904-5). Both books include a "Greetings from Chowburg" postcard but with different vignettes.

The title of the book signals that it carried the story of Johannesburg through to 1935, but the only images I can spot from the decade of the thirties (a momentous decade of depression and then revival and the rebuilding of Johannesburg) are some pictures taken from a secondary source and supposedly showing Ferreira's Town slumyards of the thirties, when Ellen Hellman's study, which the slender text refers to, was all about Rooiyard in Doornfontein and one can hardly discern a relationship between the photograph of a so called slum yard of Doornfontein (image is actually of a simple street of bungalow houses), and the suburban vista of Lorentzville and Judith's Paarl. Most of the pictures are drawn from the first decade of the 20th century.

One ends with the view that the authors did not try hard enough or take enough time over their picture research or put enough thought into what these photographs said about the shaping of working class Johannesburg. Picture research is a specialist field. I found many of the images fascinating but the continuities were less evident. The book for me was and still is an interesting picture book but is only of limited value as an historical source.

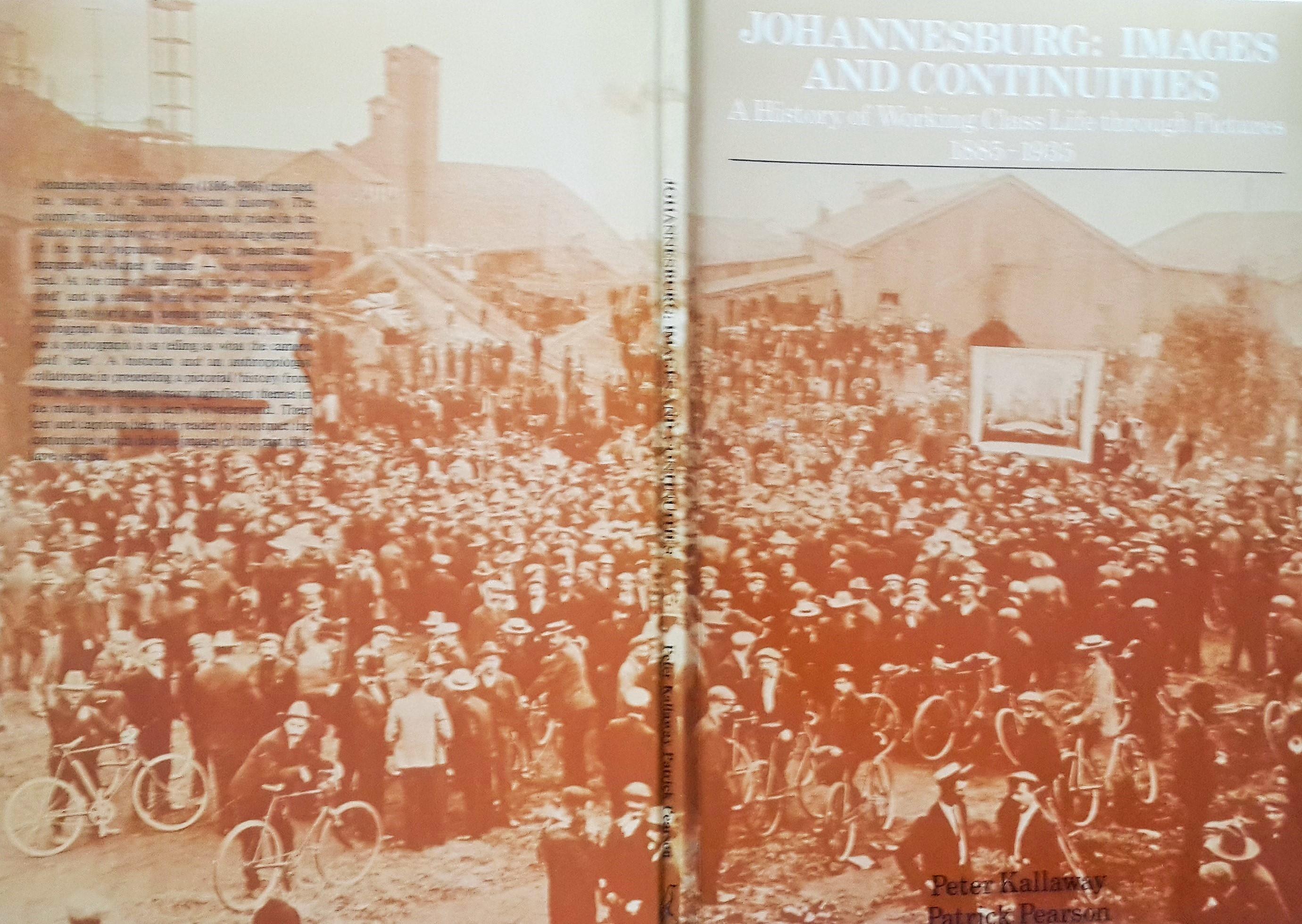

What is the cover picture all about?

The layout of the book with a dense spread of small black and white images was not very satisfactory, but cost of production and sale were kept modest to reach a wider audience. I still do not know what the one impressive cover picture of a crowd scene was all about... A gathering of male workers well dressed in weekend gear in cloth caps, homburgs, boaters, a crowd against the backdrop of mine buildings and headgear, many bicycles in the foreground. A little closer study of pages, 100 -101, with another photograph provided, pins the cover pic down to "A meeting of Germiston and ERPM strikers at Balmoral" at the time of the Miners Strike on the Rand in 1907, (illustration 265) but the illustration 266 is labelled "Strikers at Ferreira's Deep Mine waiting for scabs to come off shift", also features on the double page cover spread. Does it mean the cover picture was an amalgam of two different meetings at two places or has there been a superimposition of one photo on another? Both pictures were sourced from the Transvaal Leader Weekly for 18/5/1907. So are pictures meant to lie and who made the changes? Was it for dramatic impact or crowd management? Or just a better picture?

Illustration 265, A meeting of Germiston and ERPM strikers at Balmoral

Illustration 266, "Strikers at the Ferreira Deep mine waiting for scabs to come off shift "

The text just summarizes in a paragraph the miners struggles of 1907, 1913-14 and 1922 and calls it "Political Unrest".

Nonetheless, some 30 years since publication, the book also joins the array of older books on Johannesburg and has become an historical source of a sort. Perhaps the book is best read in conjunction with Charles Van Onselen's Studies of the Witwatersrand. Or to arrive at a more nuanced current multi-perspective, reflecting the experience of the working man or women, turn to the recently published book on migrancy and working class formation, in A Long Way Home- Migrant Worker World's, published by the Wits University Press in 2014 following the rich exhibition presented Wits Art Museum on Migrant Journeys, where the story of the workers' experience was told in art, image, souvenirs and text.

2016 Price Guide: Out of Print and price rising rapidly. Local bookshop may have a copy in the R150 range, but sale on a book auction pushed the price to $32 and hence international Internet prices come in with price quotes between $38 and $50.

Kathy Munro is an Honorary Associate Professor in the School of Architecture and Planning at the University of the Witwatersrand. She enjoyed a long career as an academic and in management at Wits University. She trained as an economic historian. She is an enthusiastic book person and has built her own somewhat eclectic book collection over 40 years. Her interests cover Africana, Johannesburg history, history, art history, travel, business and banking histories.