Review of John Maud's City Government: The Johannesburg Experiment published by Oxford University Press in 1938.

John Maud (who later became Sir John Redcliffe-Maud) was a British Civil Servant and diplomat who became an expert in local government in Britain and led the 1960s commission into local government reform. This book was written when he was still a young academic at Oxford (a fellow of University College, Oxford) and regarded as an authority on Oxford city government (he had served for 6 years on the Oxford City Council). He was an accomplished, talented and skilled researcher and writer with plenty of hands on experience in local government. He was commissioned by the City of Johannesburg in 1935 to write a book reviewing the government of Johannesburg during the first 50 years of existence, and to relate the Johannesburg experience to that of other parts of the world. He also delivered lectures at Wits University to celebrate the 50th birthday of Johannesburg. Perhaps even rarer is the short book published by Wits University in 1937 called Johannesburg and the Art of Self-Government, which was published in English and Afrikaans. I own the Afrikaans version and am still in search of the English edition.

Book cover

This book stands in sharp contrast to the sort of book that has been published as celebratory achievement volumes after a decade of ANC led city government and the several books trying to sell Johannesburg on the occasion of development conferences. None of those publicists started with Maud, but they should have. The Maud volume has become collectable because of its sober, forensic approach. It is a very practical book.

This much more substantial book, published in 1938 was the product of his studies over several years. It is a serious study of City government as it had evolved by the mid 1930s. This book is a massive tome, its sheer weight and size combined with the thick section of essential data in innumerable tables makes for a daunting read.

The first four to five chapters are historical followed by an analysis of the shortcomings of Johannesburg and the various problems of city government. The chapters that follow deal with various problems of city government and places the Johannesburg experience in the context of city government in other parts of the world, particularly Britain. The key chapter is about the Finances of City government, though equally important is the chapter on the relationship of central government to the city. How did the city work and who provides leadership?

One interesting statistic is the size of the city. In the post Boer War period the boundaries of the town extended to 52 320 acres and by 1935 had only increased marginally to 53 478 acres. The population of Johannesburg in 1903 totalled 109 000 and by the mid-thirties had grown to just under half a million people. Johannesburg in the mid-thirties was still quite a small place. Maud makes a case for an extension of the city boundaries to avoid confusion created by numerous competing local authorities. Size makes for efficiency and economy in the supply of local services (transport, electricity water being the obvious ones). Of course he also notes that by 1934 the density of population in Johanesburg was only seven to the acre, so questions of densification were as relevant in the thirties as today.

There is an interesting section on the characteristics of what Maud called “the Johannesburg system” and these features bear repeating today to set an agenda for our own time – simplicity of a single elected council, extensive powers to engage in economic activities (e.g. a city market, water, abattoir, ice manufacture and sale) but in contrast taking responsibility for only a very narrow range of welfare or philanthropic activities. The city did not provide schools nor by the mid-thirties was there a city orchestra or a theatre. The Johannesburg Public Library and the city’s Art Gallery came comparatively late and relied heavily on private generosity. It was the citizens of Johannesburg who campaigned, led by John O’Hare, to create a city University (which became the University of the Witwatersrand) established in 1922. However, through the decades as the city’s wealth increased there were improvements in public parks and sporting facilities.

Johannesburg became a city in 1928, shifting its status from town to city with mature command over its rates and management. One is struck by the maturity of Johannesburg in the 1920s when essential laws and ordinances to consolidate local government were legislated. One interesting theme is the interplay of local authority, ratepayer ambitions to run their own show and the role of provincial and national government in city administration and controls. It was only in 1931 that Johannesburg obtained town-planning powers that had been on the table for 20 years. Politics mattered in local government and Maud reflects on the people who became involved in city government in the thirties.

This is one of those dense, heavy on facts, statistics and analysis studies that will defeat all but the most serious student of the city and for this reason it has been overlooked in favour of the more popular books. It is a book for and of its time but is a rich source of information about the history and details of city government by a young man on his way to becoming a world authority on city government.

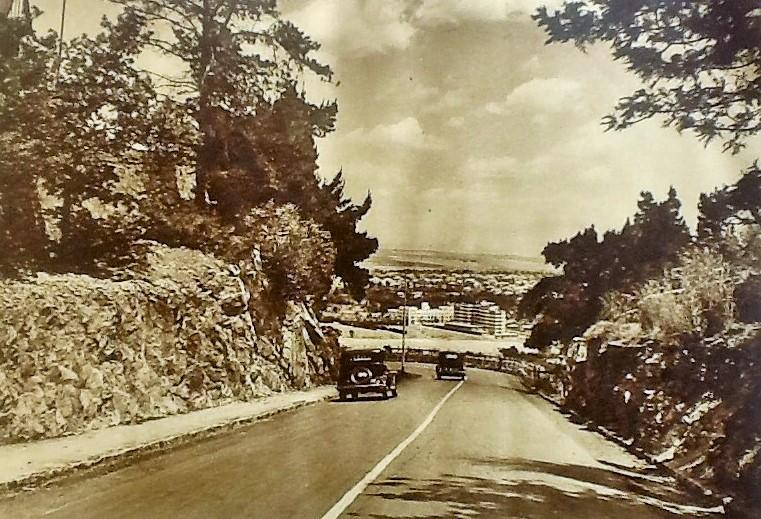

There are eight excellent black and white Johannesburg plates provided by the Rand Daily Mail giving a feel for Johannesburg in the thirties. This was the art deco city though Maud was hardly describing it as such. There is a wonderful photo of Munro Drive in 1936 described as "a suburb of Johannesburg”. Plein Square 1936 (facing page 96) in central Johannesburg (behind the old Transvaal University College) shows it to be a small symmetrical park, with the main paths crossing in an x design, scattered benches and a few new trees and shrubs. I recall that small park at the Attwell Gardens redesigned in the fifties as an oasis. Today Attwell Gardens Park has been developed (the price tag was R4.5 million) to create a safe play area with netball courts (many will argue that is has failed to live up to this description).

Munro Drive in 1936 (City Publicity Association)

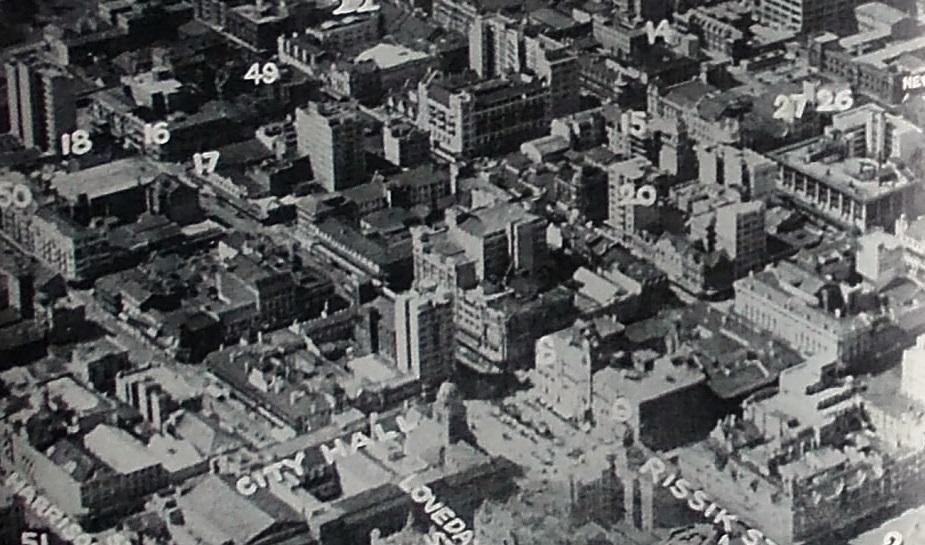

Johannesburg in the thirties was a new city, fairly contained, with downtown Johannesburg being at its core. The Art Deco city was appearing with new tall, exciting buildings such Astor Mansions, Manners Mansions, Clarendon Court, Escom House and the Ansteys Building. These were all emerging high rises that began to redefine the city in new ways. Suburbs clustered around the city’s core. Public transport was a combination of trams and buses. Maud has included two aerial views of the city in 1936 and, armed with a magnifying glass, it is a fun exercise to identify what of the 1930s city still remains. Certainly in the thirties the gold mines and the mine dumps were still a dominating presence in the landscape. Johannesburg was indeed the “golden city”.

Manners Mansions (The Heritage Portal)

Maud’s book still has relevance some 80 years later and could well be a guide to taking Johannesburg administration back to basics. Maud makes a strong case for city self-government as an art. The essential questions remain what should city government do for its city, how can it do so effectively and cost efficiently, and how should a city finance its operations. The challenge is that the city of Johannesburg is today 1645 square kms or 635 square miles.

This is an authoritative book about Johannesburg in the thirties. Don’t overlook the excellent bibliography which very usefully covers commissions of enquiry and essential Johannesburg reports before and after 1900. This book is another essential in any Johannesburg collection.

2017 Price Guide: The book is out of print but can be picked up via Amazon or Alibris books in a surprisingly low price range of anywhere between £14 and $30. Alternatively it can be searched digitally from the Hathi Trust digital files at the University of Michigan.

Kathy Munro is an Honorary Associate Professor in the School of Architecture and Planning at the University of the Witwatersrand. She enjoyed a long career as an academic and in management at Wits University. She trained as an economic historian. She is an enthusiastic book person and has built her own somewhat eclectic book collection over 40 years. Her interests cover Africana, Johannesburg history, history, art history, travel, business and banking histories. She researches and writes on historical architecture and heritage matters. She is a member of the Board of the Johannesburg Heritage Foundation and is a docent at the Wits Arts Museum. She is currently working on a couple of projects on Johannesburg architects and is researching South African architects, war cemeteries and memorials. Kathy is a member of the online book community the Library thing and recommends this cataloging website and worldwide network as a book lover's haven.