When I was invited to review this book I had hoped that I would be in for a treat about the history of photography in Southern Africa and that the visual image seized upon joyously by the scholar as evidence of past societies would reveal new sources and insights. I was initially disappointed as there is little here about the history of photography in Southern Africa from its introduction in the 1840s and the technical advances that enabled photographs to record places, events and people. This is a scholarly study and the audience will be fellow scholars in universities; but I concluded that it is a book worth exploring for its multiplicity of interpretations, ambiguities, fascinating questions and breadth. It is a book about historical method and extending historiography through a study of photographic archives.

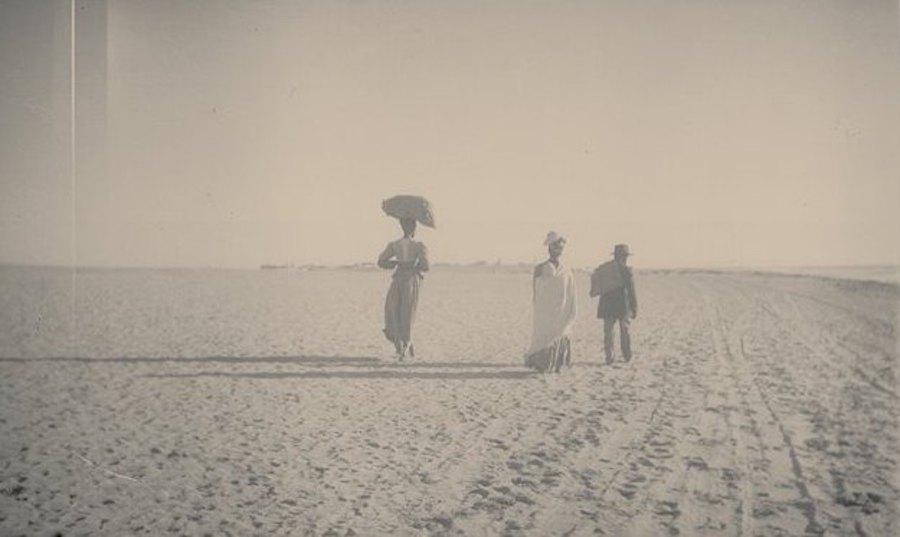

The author is not interested in the evolution of the process of capturing and fixing an image. Instead the author takes us on a journey of exploration of the photograph as evidence as to how colonial society worked in Southern Africa, i.e. in South Africa and Namibia. From the start of my reading of the book I had to rethink my own assumptions about the purpose of photography.

Book Cover

The author is an historian of Namibia and South Africa at the University of Basel and her special interests are in gender and visual history. Her objective is to probe the historical status of photography and its status as evidence that gives meaning to the colonial past. She breaks new ground in examining how the historical method and enquiry are extended through examining photographs within the context of a particular problem. She intertwines South African and Namibian colonial rule (I am not convinced that the two countries should be conflated in a single study); and unapologetically writes Namibian colonial history into South African visual documentation. The author sees the colonial archive covering both countries – although then I would ask - well why not a nod to the photographic image found in the archives of Botswana, Lesotho, Zimbabwe and so on. Of course there is a case to be made for colonial rule in the two countries having commonalities and this would take us back to the time of the explorers of yore who wandered through the whole of the southern sub-continent with wonder and awe and recorded their observations in watercolours, oils and sketches and only much later were the advantages of the camera seen. The cumbersome nature of the camera, glass plates and time exposures meant that the studio was more likely to be the site of the art of the photograph than the scenic landscape in the 19th century.

This is a rich scholarly study and one that relies not so much on the visual image or even on interpretation of that image but rather on reading the image for what it can reveal about colonial hierarchy, rule and assumptions. The author critiques the colonial archive. She argues that the serious scholar ought to be suspicious of colonial knowledge production. She sets out to refine and elaborate on the ambiguities and complexities to be found in the photographs of the official archive. What do photographs really reveal and what are their limits? I am intrigued by this approach. Overall this is a complex and deep study of the relationship between photography and history. Reading the introduction is an essential route into the mind and methodology of the author. There is a comprehensive bibliography and the research notes are impressive.

The chapters stand as separate studies of photographs drawn from a variety of archives at different moments in time. The common theme is what the photograph tells us about colonial rule; the archive is specific to the policing of people and place whether as criminals or as citizens wishing to travel and require passports or as a land management technique.

The first chapter looks at a collection of police and prison photographs and texts from Namibia under German colonial rule just prior to World War 1. Her study reveals that photographing and fingerprinting does little to advance the science of criminology but reveals more about state anxieties, racial categorization, assumptions by the state and surveillance. It’s a fascinating but grim account of the misuse of photography by pseudo-science.

The second chapter switches to South Africa and the theme is again that of state control over people using photographs to identify, classify, issue passports and determine race during a forty year period from the 1920s to 1960s. I had always wondered when passports were introduced (in fact they go back to the 15th century in England). But when did photographs become a component? Passports do not belong to the individual but are a travel document issued by a government to a citizen to enable the holder to “prove” who he or she is when crossing borders. Today we accept the state tracking of information with biometric data - the mapping of the iris in the eye; the machine taken photograph; or the finger print. The art of control of people by passport of a special type has been perfected by the Americans. I am astonished when I join the hundreds of newly arrived passengers at the Los Angeles airport all running as they step off the plane to get into the interminable queues to be machine processed. It is perhaps less fearsome when one produces a passport and visas for entry into Europe or Britain. With those experiences behind I wonder about the singularity of the South African experience but the author’s argument once again about state control over people is convincingly made. I found myself wanting to know more about how passports evolved and how travel shifts from the concept of a letter of introduction to population registration and documentation.

Then the scene switches back to Namibia and photographic images - many quite informal, for the period 1930s to 1960s. The author explores the problem of the moment when a photograph is taken. It is called the Augenblick. In other words what it means when a transient moment of the camera click is fixed in time and becomes the point of interpretation. Settler images were a particular category of image that portrayed a particular understanding of the country and society German colonists had come to govern. This is contrasted with the images captured by itinerant African photographers. Memory becomes distorted through the moment of the image on film. Here I found myself thinking about my own family and those black and white pitifully few, photos of grandparents who died before I was born or a great uncle killed in the Battle of the Somme - all one has is a photo image to “know” the ancestor. Yet how precious those photographs are. This chapter whilst grappling with the aesthetics of the photograph fits less easily into the key theme of the book as it moves more into the “private world“.

For me the most fascinating chapter is the one on the early days of aerial photography in the Eastern Cape between the 1930s and 1960s. The interest here is in military surveillance over the landscape and then in the subject of why aerial photography mattered in managing the physical separation of people according to race during the segregationist and the apartheid eras. Aerial photography on a large scale was possible through the development of the airplane, but the earliest known aerial photographs of the Witwatersrand were by Swiss-Italian stuntman and air balloonist Edward Spelterini. I am interested in Spelterini and his work and stunning photographs of the Pyramids and indeed he was the most extraordinary traveler, as well as being a showman and an artist.

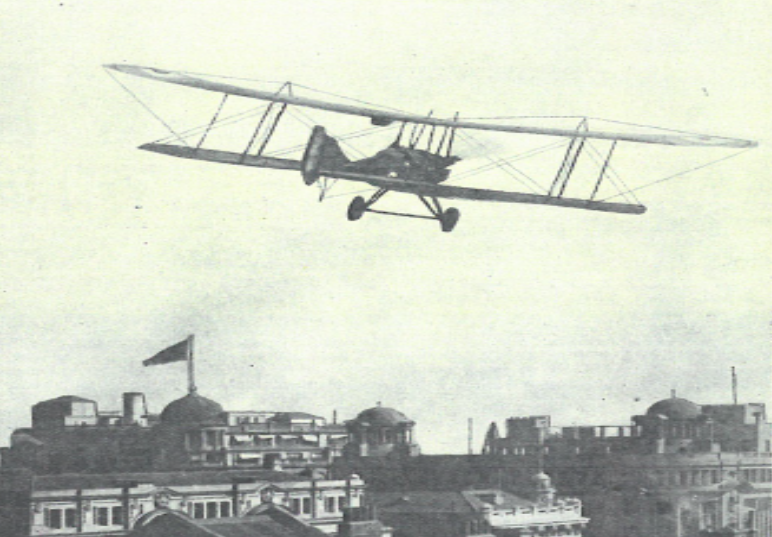

Then in the 1922 General Strike and insurrection, the new South African Air Force (established in 1920 took the earliest aerial photographs of Johannesburg for the purposes of an effective operation and a pinpointing of attacks on the strikers. Some aircraft were actually shot down by ground fire. This is an interesting account of the history of aerial photography and its military application as well as the possibilities for the survey of farms. The focus narrows to the Eastern Cape and the use of aerial photography by the Native Affairs Department, post World War II. The author concentrates on a specific album of photographs in the archive and draws conclusions about managing development and what these photographs tell about purpose and intent. It occurred to me that photography of this type needs to be linked to the efforts of the geographers to map and understand rural development. It’s an interesting insight but quite technically complex and cuts across several disciplines.

Plane flying over Johannesburg during the 1922 revolt

The final chapter is about photographic albums of the Breakwater Prison between the 1890s and 1900s. In this chapter the author completes a circular journey and reverts to the 19th century colonial world. She presents a fascinating rogues’ gallery of convicts in Cape Town and asks pertinent questions about purpose, what the photographs reveal and what was the intention of prison management in taking mug shots with hands positioned in front of the chest. Again it is an interesting but rather grim subject. The author diverts to personal musings when she finds photos of a convict with the same name as herself, Rizzo, and this raises possibilities of genealogical research in such albums, if you wish to look for such ancestors who ended up in prison. But such images whilst they add a dimension to family history reveal little beyond the photograph about the person or his criminal history. Today we take photographs of a prison population very much for granted, but here is an effort to trace the origins of this genre of photography with a specific example.

Overall, I found the book a fascinating introduction to looking at a different type of photograph and in a different way. So many questions are raised about social history and the hierarchy of controls governments imposed on its population. Photography is one such method. The book is the product of extensive and detailed research in many photographic archives. The subject is complex because historiographic theory is central to interpretation. The text of the book is not an easy read - I found myself reading and rereading sentences and then paragraphs. The author is interested in photographs as a route into a particular kind of historical understanding of colonialism in Southern Africa. This is an academic study and breaks new ground in probing ways to look at photographs in order to deepen knowledge, interpretation and understanding of the colonial world and how that world shaped our own.

Kathy Munro is an Honorary Associate Professor in the School of Architecture and Planning at the University of the Witwatersrand. She enjoyed a long career as an academic and in management at Wits University. She trained as an economic historian. She is an enthusiastic book person and has built her own somewhat eclectic book collection over 40 years. Her interests cover Africana, Johannesburg history, history, art history, travel, business and banking histories. She researches and writes on historical architecture and heritage matters. She is a member of the Board of the Johannesburg Heritage Foundation and is a docent at the Wits Arts Museum. She is currently working on a couple of projects on Johannesburg architects and is researching South African architects, war cemeteries and memorials. Kathy is a member of the online book community the Library thing and recommends this cataloging website and worldwide network as a book lover's haven.