Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

Durban, to me is a motley memory of youthful, carefree and sunny beach holidays. While Cape Town offers stunning vistas, top-end restaurants and a sense of Europe-in-Africa, it somehow feels clinical in comparison. The exotic fragrances, clamour, sub-tropical climate and personal recollections are what most attract me to this colourful Indian Ocean city.

A recent trip to the KZN South Coast concluded with a visit to the historic Brook Street cemetery. Driving down Theatre Lane, the din produced by a multitude of taxis, passengers and street vendors soon faded as I entered this peaceful oasis. Exiting my air conditioned vehicle in early winter, I found the climate pleasantly warm with just a hint of humidity. Glimpsing a snake charmer entertaining a crowd on the far side of the cemetery fence, my senses momentarily confused, I briefly pondered whether I was still in Africa, or somehow magically transposed to the Indian subcontinent.

This historic cemetery, surrounded by interesting markets and vernacular architecture, offers much to see and appreciate (see main photo with ‘The Mansions’ building dating from 1904).

My rather tattered copy of ‘Durban’s Heritage explored … on walks and drives around the City’, as always proved very useful, although many of the street names have changed since first published.

This cemetery, previously known as the West Street Cemetery, is still very well maintained and safe to visit. It is a veritable ‘Who’s Who’ graveyard of early settlers to Port Natal, or Durban as it was subsequently named.

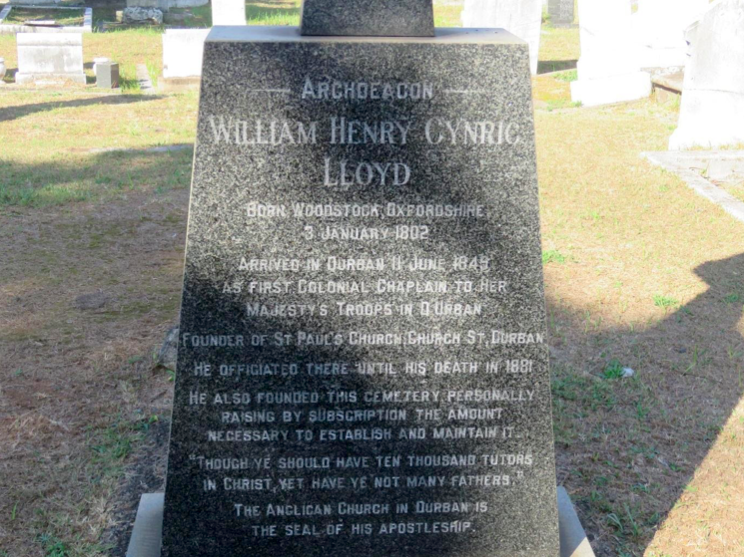

Tombstone of Archdeacon W.H.C. Lloyd, founder of this cemetery (SJ de Klerk)

According to the ‘History of Old Durban’, the Rev. W.H.C Lloyd induced the Governor to approve the reservation of a ‘God’s Acre’ at the West End of town and enclosing the graves already there, as a General Cemetery. The Surveyor General, William Stanger, mapped out an area of 100 yards square and the title deed was issued to the Bishop of Cape Town in January 1850. Rev. Lloyd went on to raise funds and encourage the public to enclose and lay out the ground. Convicts dug a ditch and arranged the grounds, while funds to construct the wooden gates were obtained through a general parish levy.

As the city expanded so too did the cemetery, and this symbiotic relationship only terminated many years later when the city authorities appropriated some cemetery land to extend Russell Street and construct the spur of the N3 between the cathedral and the above extension. Apparently 300 catholic grave sites containing the remains of some 503 deceased had to be relocated because of these road extensions.

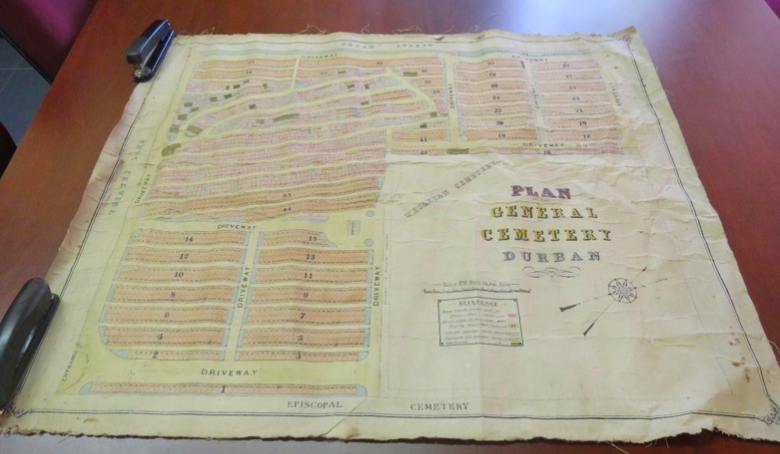

Old map of cemetery, circa 1894. Current access from left (South) via Theatre Lane (SJ de Klerk)

Over time the layout of cemetery changed somewhat, and the only road access now is from Theatre Lane. The old map above provides some orientation and the section at the bottom, left, (south/east) is where the older graves are found.

A few meters past the entrance and just before the coffin rest, lies the historic grave of Ensign John Morley of the 27th Inneskillings Regiment. He was killed at the entrance of the harbour on 2 June 1842, during the Siege of Port Natal. This is probably the oldest identifiable grave here.

Tombstone of Ensign John Morley of the 27th Inneskillings Regiment (SJ de Klerk)

Almost adjacent rests the tombstone of Captain William Douglas Bell. His interesting epitaph reads; ‘In memory of Captain William Douglas Bell. 25 Years Port Captain of this Port. Died 10 April 1869 aged 62 years. At the taking of Port Natal from the Insurgent Boers, he rendered valuable service by towing into Port under fire of the enemy, the boats of the Southampton frigate, and through his after career in life, was held in esteem as a faithful servant of Government, a good husband and affectionate father’.

Tombstone of Captain William Douglas Bell (SJ de Klerk)

Slightly further along but on the right-hand side of the roadway is the ornate, yet attractive tombstone of Sir David Hunter, K.C.M.G. Appointed in 1879 as the first General Manager of the Natal Government Railways, he retired in 1906 and died in 1914. He was responsible for increasing the length of the Natal railways from a mere 80 to a far more respectable 1300 kilometres. Upon retirement he entered politics and represented the Durban Central constituency in the Union Parliament from 1910, until shortly before his death.

Tombstone of Sir David Hunter K.C.M.G. William Stanger’s monumental tombstone is visible to the distant left (SJ de Klerk)

Proceeding past Hunter’s grave and just beyond the corner where the roadway turns left (West) towards the cemetery offices, lies the grave of George Christopher Cato, first Mayor of Durban. Cato came to the Cape with his father in 1826 and settled in Grahamstown. After joining the firm of J. O. Smith in Port Elizabeth, he was sent to Natal to open new trading stations. His first public service soon after arrival was to take the ship Mazeppa, formerly a slaver to Delagoa Bay to rescue the survivors of the Trichardt Trek. He was only able to bring back about two men and 60 women and children. To Cato also belongs the honour of laying out the town of D’Urban, which he did in 1840, under instructions from the Volksraad in Pietermaritzburg. He had business connections in every part of Natal and was said to be legal adviser, storekeeper, landing and shipping agent, banker, timekeeper. In addition to the above he also served as Consul for the USA, Denmark, Norway and Sweden. He died in 1893, a man apparently greatly loved by all who met him.

Tombstone of George Christopher Cato (SJ de Klerk)

Near Cato’s grave rests the monumental tombstone of the first Surveyor-General of Natal, William Stanger. He died unexpectedly in March 1854, aged merely 42 years and his funeral was large and imposing. The Lieutenant-Governor, local civil servants, officers from the military camp and 120 townsmen dressed in black followed. Shops along the way were closed and in the typically flowery 19th century narrative style, it is said the Bishop of Natal, assisted by the Rev. W.H.C. Lloyd conducted the service in a most solemn and impressive manner. The site of the grave was selected by Lieutenant-Governor Pine under a wide-spreading flat-crown tree. Pine also originated the design of the imposing tall column. His tombstone was placed fronting the main entrance and pathway of that period.

Monumental tombstone of Surveyor General William Stanger (SJ de Klerk)

Stanger’s constitution had been weakened by an expedition to Niger in 1840-41. Every member of the party contracted malaria and the party would have perished, if Stanger and another man had not brought the survivors out of the area and back to England. He then moved to the Cape where he served the Colonial Government as a geologist, naturalist and surveyor. When the British government took over Natal it quickly realised the area was totally uncharted and Stanger was sent from the Cape to remedy this deficiency. The lithographed map he subsequently produced was invaluable at the time, not only for administrative purposes, but also for emigration promoters like Joseph Charles Byrne who used it as part of the prospectus.

The epitaph engraved by James B. West is now badly weathered and difficult to read. The town of Stanger, now KwaDukuza was named in his memory.

Slightly to the south/east of Stanger’s grave lies the tombstone of one of South Africa’s most prolific 19th century artists and explorers, Thomas Baines, F.R.G.S. Baines travelled through much of South Africa, Botswana, Namibia and Zimbabwe and visited Australia and the East Indies. Born in King’s Lynn, England, he died in Durban in 1875 from dysentery.

Tombstone of Thomas Baines, looking east (SJ de Klerk)

The original epitaph reads: ‘This stone is erected by some of his loving friends and comrades who, amid hardship and perils, undergone in the interior of this continent, learnt to appreciate the nobility of his character’. A later addition reads: ‘The original stone having crumbled through age, this replica of it was erected by the Durban Corporation at the instruction of the SA National Society in 1966’.

In 1940 when the cross surmounting the memorial was in danger of collapsing, the late Sir Charles Smith K.C.M.G., the Natal sugar magnate, parliamentarian and Union Senator, not only met the cost of the renewal but also paid the cemetery authorities the requisite fee to ensure the maintenance of the grave site in perpetuity. Sad to relate the ongoing weathering of this tombstone may soon again necessitate restoration.

In this vicinity is the attractively engraved tombstone of Henry Francis Fynn, often referred to as the ‘First Natalian’. Born in London in 1803, he studied at Christ’s Hospital, (the ‘Bluecoat school’) where he obtained an elementary knowledge of surgery and the medical science. Joining his father in Cape Town in 1818, he subsequently travelled as trader to Delagoa Bay, now Maputo, where he met Lieutenant Francis G. Farewell. He and Farewell agreed to establish a trading post in Port Natal to secure a share of the profitable inland ivory trade.

Farewell, accompanied by a group of Whites and Khoisan arrived at Port Natal in May 1824, with Fynn joining them some six weeks later. The two of them travelled through hostile countryside to Shaka’s royal village, Bulawayo, near the current Eshowe. Fynn remained there when Farewell returned to Port Natal. Following an unsuccessful attempt on Shaka’s life, Fynn nursed him back to health and was consequently awarded a sizeable allotment of land, approximately forty by one hundred and twenty kilometres, for use by the White settlement at Port Natal. From 1834 to 1851 he served in the Cape Colony in various government roles. He returned to Natal in 1852 upon appointed assistant magistrate for Pietermaritzburg but retired from public life in 1857 due to his declining health. His remaining years were spent on the Bluff, where he died deeply disappointed because the government repeatedly refused to accede to his reasonable requests for a land grant.

Tombstone of Henry Francis Flynn (SJ de Klerk)

In the older sections of the cemetery are several graves associated with the military. The tombstone of Gustavus Morton Green is particularly interesting, as he was killed on the Zulu Border in 1879. His epitaph reads, ’In loving memory of Gustavus Morton, Isipingo Mounted Rifles. Only surviving son of T.R.M. & R.L. Green. Killed on Zulu Border on 2nd June 1879. In the midst of life, we are in death’.

Tombstone of Gustavus Morton Green (SJ de Klerk)

I was unable to find any reference to Green, in my admittedly limited library on the Anglo Zulu War. Major Tylden describes the Isipingo Mounted Rifles thus; ‘Formed near Durban in 1879. At the close of the Zulu War, most of the members transferred to the Alexandra Mounted Rifles, and the corps ceased to exist. Served on the Zululand frontier, strength 40. The commanding officer was Captain Dering Stainbank’.

Green was killed merely a day after the Prince Imperial, probably in one of the numerous minor skirmishes and ambushes occurring, before the war ended with the comprehensive defeat of the main Zulu impi at the Battle of Ulundi on 4 July 1879.

The Doble grave site is rather sad. The main tombstone commemorates the parents, George Robert, a Pioneer of Kimberley and Johannesburg and his wife Elizabeth Phoebe, but it is the smaller monument to the fore of the grave that is particularly sorrowful. It is to the memory of their three sons who were all killed in action. George Charles Robert of the Mounted Ambulance Corps at Spionkop on 20 January 1900, aged 23 years. The two younger brothers were both killed in France during the 1916 Battle of the Somme (1 July – 18 November 1916). Henry Wood of the Royal Warwickshire Regiment on 3 September, aged 20 years and George Robert Frederick of the South African Scottish, barely five weeks later, on 12 October, aged 18 years. George Robert Frederick was most likely killed during the assault on the Butte de Warlencourt.

The Floo'ers o' the Forest are a' wede away. Monument to three young Doble brothers killed in the Boer War and World War 1. (SJ de Klerk)

Durban has always been an important harbour on the Southern African coastline and many of the graves confirm this. There is an interesting monument to officers and men of the torpedo ship HMS Tartar, who died in places as diverse and distant as Luanda, Mombasa, Zanzibar, Durban, Mooi River and Estcourt. The nomenclature ‘Krooman’ indicated next to the name ‘Tom’ is noteworthy as many of the Royal Navy ships employed locals from West Africa to perform certain tasks aboard ship. Called Kroomen by the sailors, these men were hardy, experienced in the handling of small boats, and resistant to malaria. Hence, they played an important role aboard the smaller craft of the Royal Navy patrolling the East African and West African coastlines to suppress the slave trade.

Monument to Officers & Men of HMS Tartar. Note the snake charmer beyond the fence to the right. (SJ de Klerk)

The tombstone of the Reverend Horatio Pearse, Wesleyan Minister, is unusual and shows a mourner praying at a classical tomb covered by an urn wrapped in a shroud. An open book symbolising a bible and hence Christian faith, rests against the tomb.

Tombstone of the Reverend Horatio Pearse (SJ de Klerk)

For some reason, tombstones in the Art Deco style are rarely found in South African cemeteries and it was therefore pleasing to discover this attractive example, dedicated to the Shearer family.

Art Deco tombstone of the Shearer family (SJ de Klerk)

Moving to the northwest, I was disappointed to find both the Parsee and Jewish precincts closed to the public. In India, the remains of those of the Parsee faith are placed on high pillars called ‘towers of silence’, upon which birds of prey descend to devour the dead. In South Africa such practice is forbidden, and the small South African Parsee community accordingly bury their dead in public cemeteries. In Johannesburg, there is still a small but still active Parsee precinct in the Braamfontein cemetery.

Peering through the gate of the tiny Parsee cemetery (SJ de Klerk)

It seems the Jewish precinct only became available in 1880, some thirty years after the cemetery officially opened. The first official Jewish burial in South Africa had taken place more than four decades prior in Grahamstown.

The Jewish Precinct (SJ de Klerk)

The Muslim Cemetery on the other hand is still active, beautifully maintained and numerous people were present at the time of my visit. Visitors prayed or meditated at the tomb of Badsha Pir. He was one of the two Islamic saints who lived in Durban, having arrived as an indentured labourer, but honourably discharged not long afterwards. Many miracles were attributed to him and it is recorded that he lived in a constant union with God.

Tomb of Badsha Pir (SJ de Klerk)

A Muslim grave inscribed with the phrase ‘Hagee’ indicates the deceased went on a pilgrimage to Mecca, whereas ‘Hafez’ reveals the departed memorised the Quran in its entirety. Notice that almost all the graves have the number 786 which is considered a sacred number in the Islamic faith.

The grave of Aboobaker Jhaveri is also situated in this cemetery. He was the first Indian trader to set up business in 1872 in Durban. In 1893 he asked a young Indian Lawyer named Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi to take up a legal brief on his account. This was the start of Gandhi’s association with South Africa, lasting twenty-one years until 1914, when he returned to India.

Another prominent grave in the Muslim precinct is that of Dr Rick Turner, the young academic and anti-apartheid activist, murdered in 1978, most likely by the South African security services.

Tombstone of Dr Rick Turner (SJ de Klerk)

This historical cemetery is most definitely worth visiting and hopefully this article will entice those wishing to increase their knowledge of early times in Durban and Natal.

About the author: SJ De Klerk held many senior positions in HR during a distinguished career in the private sector. Since retiring he has dedicated time and resources to researching, exploring and writing about South African history.

References

- Buchan J. (Not dated). The South African Forces in France. Thomas Nelson and Sons Ltd. London.

- Campbell K. Mr. G. C. Cato. In Africana Notes and News. (March 1957, Vol. 12, No.5). Africana Society, Africana Museum, City of Johannesburg.

- Clark J. Dr W. Stanger, Natal’s first Surveyor-General (1845-1854). In Africana Notes and News. (June 1972, Vol. 20, No.2). Africana Society, Africana Museum, City of Johannesburg.

- De Kock W. J. (Hoofredakteur). (1976). Suid-Afrikaanse Biografiese Woordeboek Vol 1. Tafelberg Uitgewers Bpk. Kaapstad.

- Email correspondence between Ms Jane O’Connor & Professor Brian Kearney regarding previous road extensions impacting on the cemetery ground. (2015).

- Johnston P. & Naidoo H. (Not dated). Durban’s Heritage Explored …on walks and drives around the City. Adams Co. (Pty) Ltd.

- Russell G. History of Old Durban. (Reprinted 1971). T. W. Griggs & Co. Durban.

- The Grave Stone of Thomas Baines. In Africana Notes and News. (March 1966, Vol. 17, No.1). Africana Society, Africana Museum, City of Johannesburg.

- Tylden G. The Armed Forces of South Africa. (1954). City of Johannesburg Africana Museum Frank Connock Publication No. 2. Johannesburg.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.