Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

A modern photographic phenomenon that has emerged is “found photographs” – these include everyday snapshot photographs taken by others years ago, but have subsequently been discarded. These discarded photographs can today be bought up cheaply by photographic curators at car boot sales, charity organisations, fairs or auctions (online auctions included). These photographs are typically found in old photo albums, boxes with photo-odds or photo sleeves holding old prints.

As a single image, any “found”, or the converse thereof, “lost” photograph has sadly lost its original context when viewed by a total stranger who would not necessarily comprehend the context in which the photograph was taken in the first place. A different context can however be provided again when “lost” images are clustered together into a theme, such as those presented in this article.

“Found” photographs ultimately do create a sense of nostalgia for some.

Whilst any other theme could have been selected, photographs of vintage automobiles are used in this article to reflect on the concept of snapshot photography. At the time these snapshot photographs were captured, the vehicles were probably new. Today, most of these vehicles are more than 60 years old, resulting in us looking at them as classic or vintage automobiles.

This article not only reflects on snapshot photography itself but also on the visual evidence and human stories around the importance of car ownership. The photographs included provide for a visual narrative, reflecting on the cars bought, driven, occasionally raced, sadly crashed, sometimes cursed, often scrapped, potentially hated by the earlier generations – and then, of course loved - all aspects confirmed by the photographs presented.

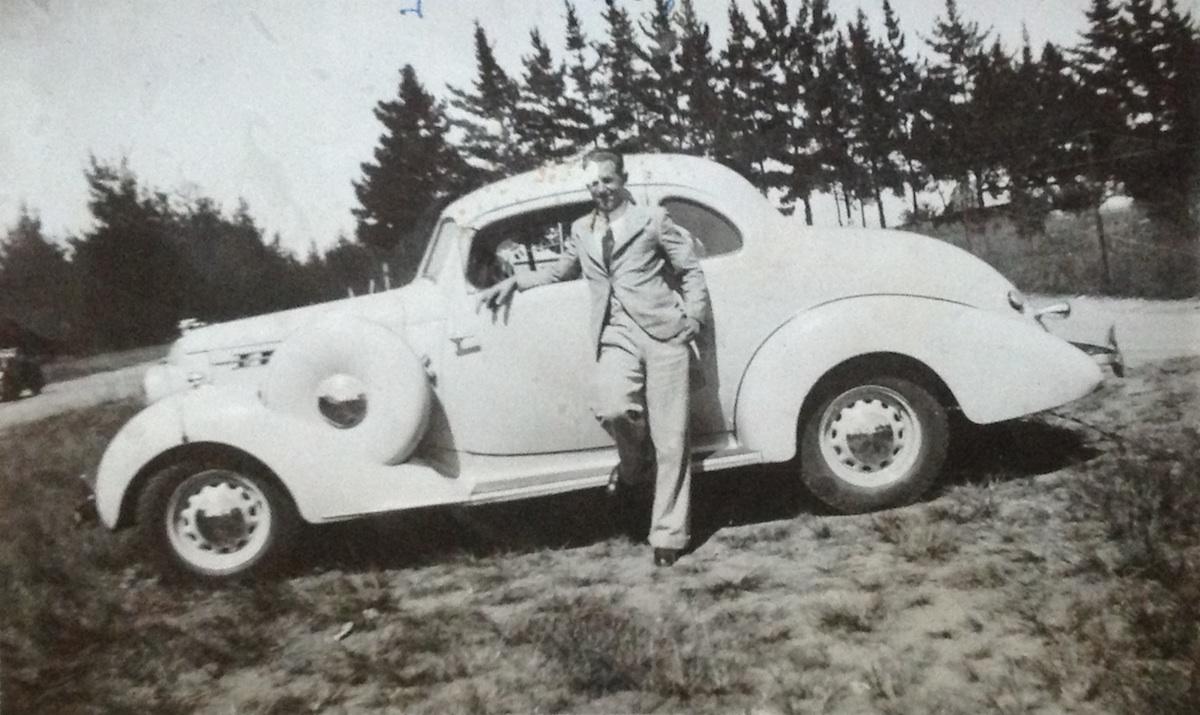

Richard Knoop with his 6-wheel Plymouth (1935/6). Described as the poor man’s Mercedes

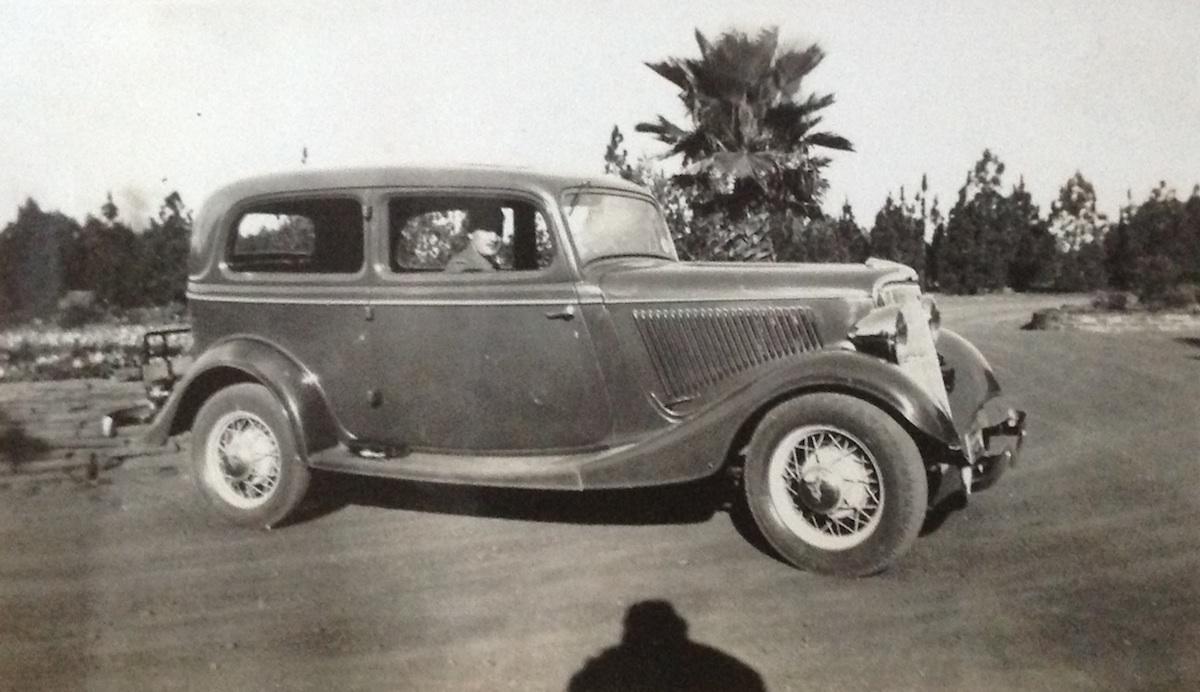

Ford V8 (1934). Typical of snapshot photographs is where the photographers shadow appears in the image.

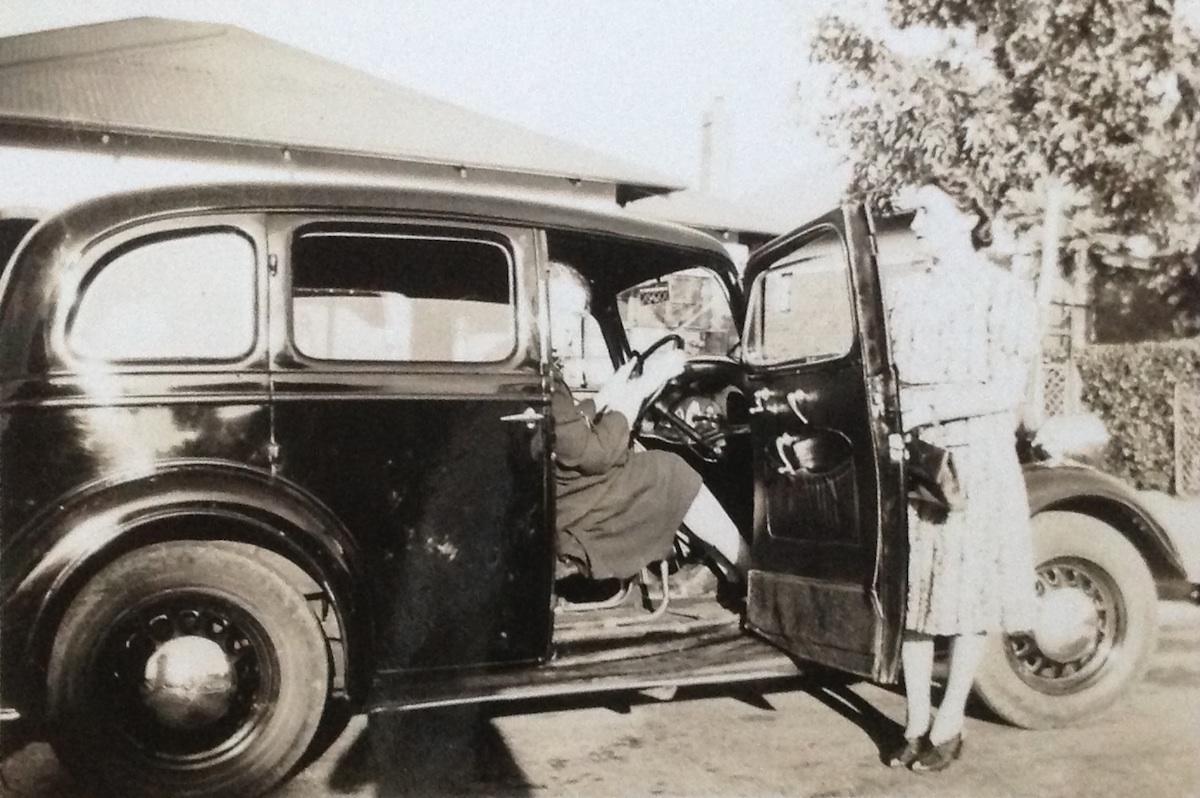

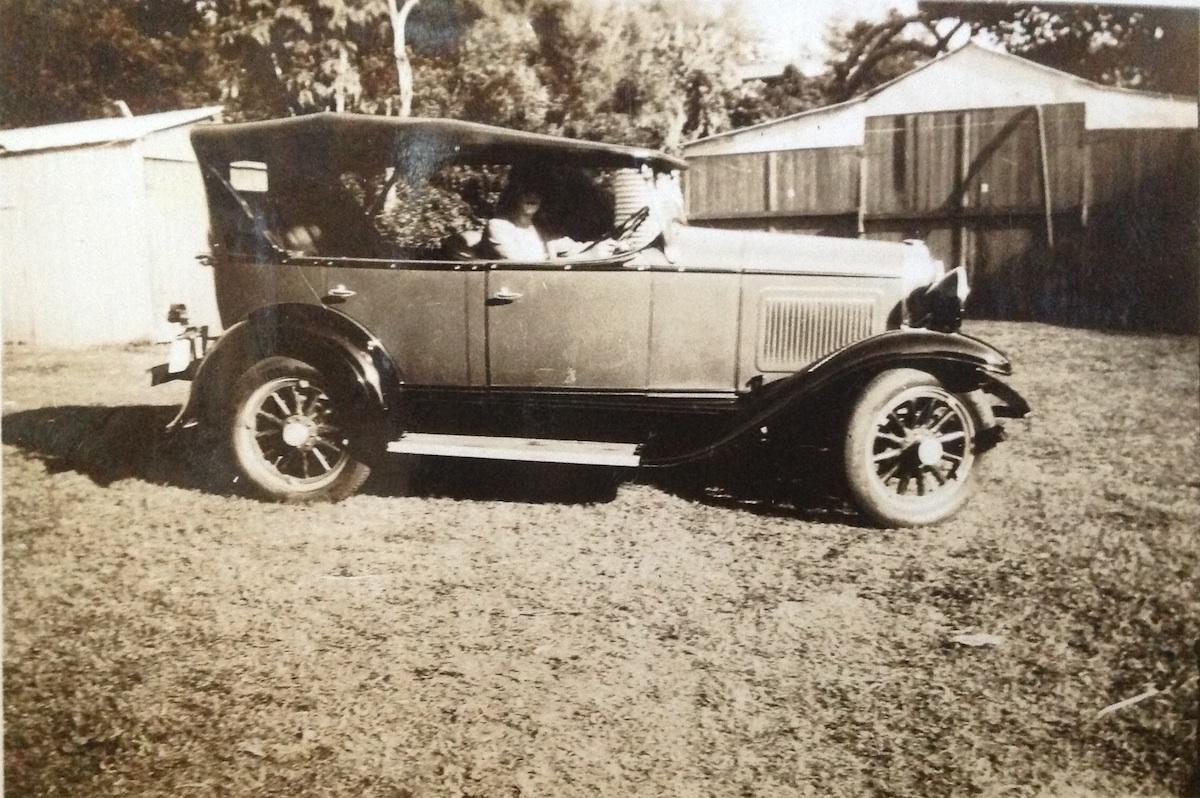

Late 1920s soft top – manufacturer unknown. This image is also of interest due to the fashion presented by the two ladies. Note the wooden spokes

Although the author’s main interest remains in antique photographs prior to 1915, he cannot reject the occasional snapshot photograph scratched out (or “found”) relating to old cars. This is ironic in a way, as he has no knowledge or interest in old cars – only appreciation.

Car enthusiasts from a Gauteng based car club assisted the author in identifying the various cars in the snapshot photographs included in this article. It was the earlier models that proved to be a challenge in terms of identification. It is therefore acknowledged that some of the models stipulated in the captions may be incorrect.

Snapshot photography in South Africa

Modeled on painted portraits, the photograph emerged in the early 19th century.

Not long after the invention of photography, South Africa’s first professional photographer, Julius Leger, established himself in Port Elizabeth during 1846.

Until around the 1880s, photographic equipment was bulky and used mainly by professional photographers. The capturing and development of photographs was also a difficult process involving long exposure times and complex chemical processes.

Photographs during the mid to late 1800s were described as studies in stiffness in that taking a picture then required the subjects to sit still for 30 seconds or more. Sitters were sitting straight, too afraid to move - or even to change their facial expression - for fear of a blurred image. In short – capturing a spontaneous image then was not possible.

Snapshot photography came into play during the early 20th century, thanks to Eastman Kodak. The first such images in the South African context were photographs taken by the warring parties during the Anglo-Boer war. Snapshots were taken mainly by the British soldiers, who brought their new, modern hand held cameras along from England.

1939 Ford Mercury – Note the Johannesburg number plate

Snapshot photography soon became an international craze. Various forms of the word “Kodak” entered common American speech such as kodaking, kodakers, kodakery. By 1898, just ten years after the first Kodak camera was introduced, one photography journal estimated that over 1.5 million roll-film cameras had reached the hands of amateur snapshot photographers.

“You press the button, we do the rest,” was the Kodak slogan that elevated snapshot photography. Later Kodak advertising urged consumers to "celebrate the moments of your life" and find a "Kodak moment".

In a South African vernacular, Mik-‘n-Druk (aim-and-press) also became a common descriptor in the latter years, clearly describing the ease of use.

By simplifying the apparatus and even processing the film for the consumer, Eastman Kodak made photography accessible to millions of casual amateurs with no professional training, technical expertise, or aesthetic inclinations. The initial Kodak camera offered simplicity - it arrived with 100 exposures preinstalled, and when they were taken, the entire camera was shipped back to the factory for development, where workers developed the photos and mailed them back to the owner along with the reloaded camera.

It still needs to be confirmed whether this same option was available within South Africa to the South African amateur photographers at the time.

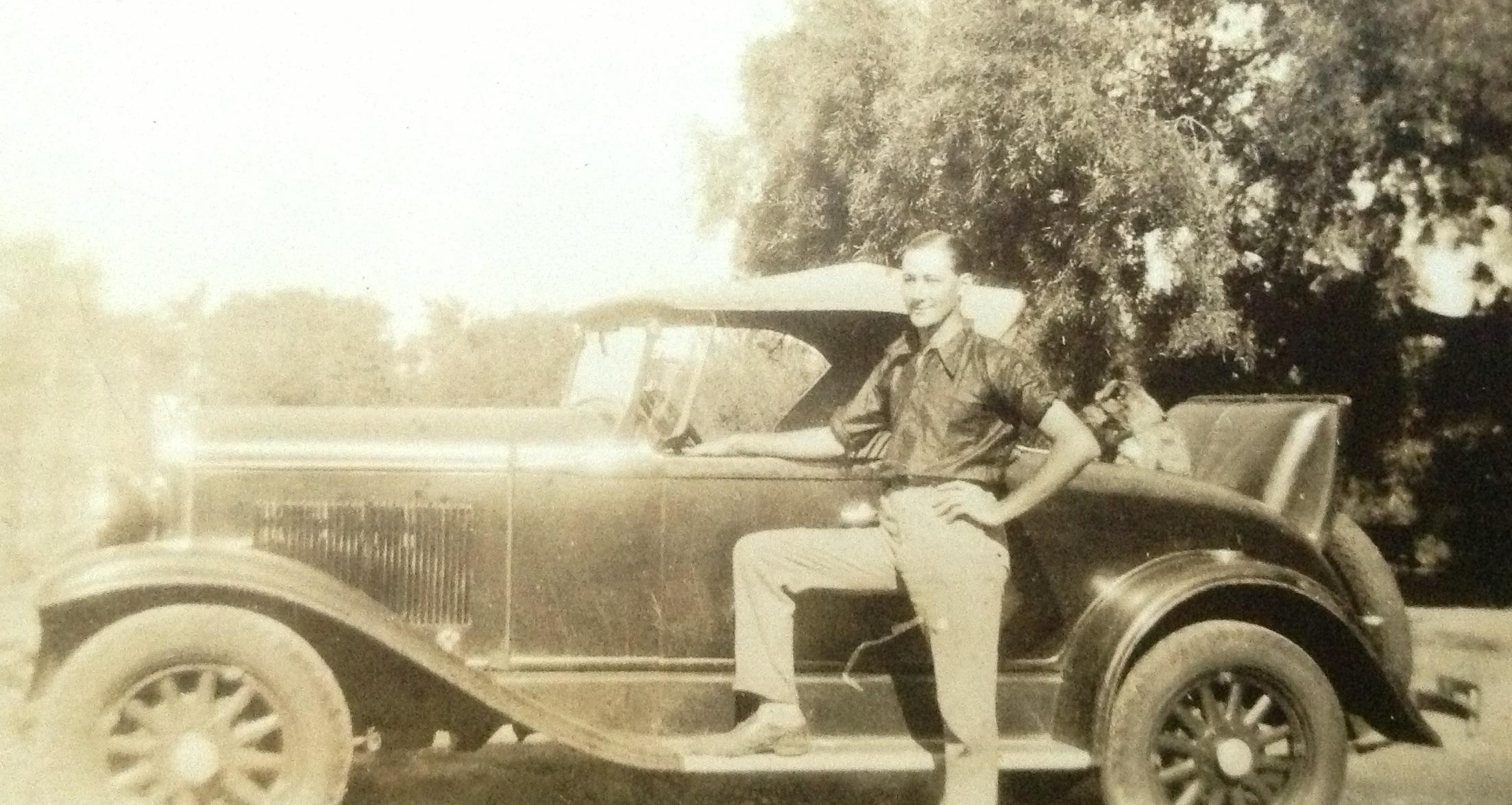

Dodge tourer from around 1926. Note the wooden spokes

Fuel carrying (Shell) Leyland Albion truck (1920s)

Part of the freedom came from surplus – pretty much the same surplus we have today with digital and cellphone photographic technology. With 100 possible exposures in the camera, each picture became less precious in that amateur photographers simply “snapped” away without concern for composition.

A snapshot is popularly defined as a photograph that is "shot" spontaneously and quickly using a small handheld camera, most often without artistic or journalistic intent.

Snapshots are commonly considered to be technically "imperfect" or amateurish – often out of focus or poorly framed or composed. Common snapshot subjects include the general events of everyday life. Snapshots are random, accidental or caught on the fly.

Indeed, the subjects or circumstances photographed may largely have been of the mundane and every day human activity.

The increasing ease (technically and financially) of taking a photograph led to more and more people shooting spontaneously and indiscriminately. People were free to take a multitude of spontaneous photographs of their everyday lives. The author refers to these indiscriminate photographers as “happy snappers”.

Photograph dated August 1967 – Leyland Albion. Note the Branding on the door: Bafokeng Tribe - Rustenburg

A wedding photograph? A rather non-elegant pose by the bride with a 1927 Studebaker

A 1942 Morris – Poor quality photograph - typically snapshot photograph standards - Note the photographer’s shadow

The word “snapshot” is often also used to describe a photograph in a somewhat derogatory sense. A photo that was taken quickly, with little regard for composition, framing, and camera settings. A photo that was taken without much thought.

As can be seen with some of the images included in this article, little effort was made in most instances in terms of photographic composition. Shots were often also out-of-focus. The resultant images remained a spontaneous capture – a snapshot.

However, when a photo is described as a snapshot, it does not necessarily mean that it is a bad photo.

Prior to the advances in cellular technology, people also enjoyed having snapshots taken of themselves – be that of them out shopping (an example is images captured by street photographers in the late 50s to mid 60s in South Africa’s main cities), at the beach, of children with their new toys or with their pets etc. The amateur photographer attempted to capture the moments they found themselves in or stumbled upon. Playfulness and humor was also present – at least for the people related to the photographer.

More serious photography is often based around capturing the less ordinary. Subjects such as beautiful landscapes and beautiful people. Snapshot photography is the opposite.

People rarely took pictures of anything sad. It was as if, after decades of morose stiffness they were releasing themselves from the old-fashioned studio settings. Previously, in the age of the studio photo, the sitter had to pose. This suggests consent being provided resulting in automatic cooperation. With a hand-held camera, a picture can now be taken of people unawares. This created a social conundrum in that suddenly personal privacy was being exposed.

A 1931 Model A Ford. Photograph clearly taken in a well-to-do suburb.

A 1962 Vauxhall Velox

This one had the fundis arguing – A Nash? A La-Selle or a Graham? Note the Cape number plate as well as AA badge

A game even emerged called “snap-shooting”, a sort of photographic version of tag where an individual would try to escape while the photographer raced around trying to capture the individual on film. A famous photo shows a laughing, 20-year-old Franklin Roosevelt hiding behind a female relative after he was pulled into such game.

Not everyone was happy with the rise of the snapshot. Professional photographers were repelled by the weird, ungainly, often out-of-focus shots that amateurs produced. One art photographer announced “Photography as a fad is well-nigh and on its last legs”. Others in turn bemoaned the “Kodak fiends” - camera obsessives who carried their device everywhere “snapping” away.

Snapshots, of course, typically lacked any purposeful artistic expression. While galleries would exhibit photographs, it is highly unlikely any of those photographs would have been snapshots in that pictorial photographers argued that snapshot photography lacked the aesthetic sensibility and technical expertise necessary to be considered as fine art.

The snapshot itself also evolved. Eastman ingeniously realised that people would take even more pictures if they were reminded of the power of photos to preserve memories.

In the 1943 edition of Eastman’s book How to Make Good Pictures, parents are encouraged to “lifelog” their children’s every step, producing “an intimate snapshot diary covering the entire period from cradle days to full man- or womanhood.”

A photo postcard showing an Austin Swallow (Top-hat Saloon) late 1920s – Taken somewhere on the beachfront in South Africa

A 1936 P2 Rover

Probably a pre-1925 Chrysler

During the 1940s, Polaroid technology arrived. Edwin Land, the creator of the Polaroid, regarded his device as a powerful memory device. He envisioned that one day people would have a wall at home, and would be snapping all day long and posting the resultant images on this wall, an aspect that social media would achieve successfully some 60 years later.

Most snapshots produced between the 1890s and the 1950s were destined for the family album, itself an important form of vernacular expression (vernacular photography is synonymous to snapshot photography in that it also describes photographs taken of everyday life and common things as subjects). The compilers of family albums often arranged the photographs in narrative sequences, providing factual captions along with witty commentary. In a 110 year old photo album in the Hardijzer photographic research collection the original owner wrote the caption “snapshot” underneath an image of two boys playing.

Removed from their original context in the family album, these anonymous snapshot photographs take on new meanings, inviting interpretation as a uniquely modern form of folk art.

Snapshots, in a way, contributed positively to the growth of professional photography in that it encouraged professional photography to stylistically become more loose. The spontaneity of snapshots with their candid subjects, unorthodox cropping, skewed horizons, motion blur, varying lighting conditions or photographer shadows captured on the image, became a part of our visual cultural language. There was an obvious demand for less formal and less contrived images. Professionals had to find a way to bring these elements into their work and do it better than the average hobbyist who had little to no technical skill or artistic intent.

Probably a Studebaker from around 1925/26

Hudson Commodore from around 1948

Andrew Bothma sent this photograph of his 1929/31 dickey seat car to Lulu Spangenberg (Note the wooden spokes). A dickey seat is an uncovered passenger seat that opens out from the rear of an automobile.

The more professionally inclined photographer bases the image around a careful, thought through structure. Choosing a focal length, framing, composition, depth of field, and shutter speed to create a picture that shows what they want to highlight about a subject, while eliminating or at least reducing what does not need to be shown. Their photos are therefore often planned and some take a lot of work to bring about.

One good example of such professional photographic imagery (amongst many other South African photographers) is the work produced by Obie Oberholzer.

For images used in this article, no photographer details are available – a common aspect for most snapshots or “found” photographs. The images are mainly smaller format prints (8,5 x 6 cm) with a small white frame. This frame has been cropped out for most of the images presented in this article.

It was the proud vehicle ownership, and the “happy snappers” that produced this endless source of photographic images. Multiple alternative thematic themes are possible to put some of the “lost” images back into some context again, albeit a different one to the original context – for example, children and their toys.

Not to be ignored. If adults may have prized possessions, so can I (Peddle car – Chief Fire Engine).

Brief history of the first car in SA

Times have changed immeasurably since South Africa's humble motoring beginning at Berea Park in Pretoria 120 years ago. The first car in South Africa predates the Model T Ford. This “horseless carriage”, a Benz Velo, imported by a local businessman, John Percy Hess, arrived in South Africa at the end of 1896.

Ironically, it did not run under its own power until January 4 of the following year. This was because there was a delay of a month in the arrival of the benzene fuel for the engine.

The first public demonstration of this car took place at the Berea Park sports ground in Pretoria. Paul Kruger, the President of the Transvaal Republic was present on the day of the introduction. The public announcement around the event urged Pretorians to attend this all-important event proclaiming that “the motor car, like the bicycle, has come to stay and will be the craze of the century.”

Accidents do happen – A “Studio Pfohl” photograph taken of an accident scene in Kroonstad. Note the time on the Dutch Reformed Church clock (17h30). Circa late 1940s.

Early 1960s Opel Car-a-Van.

Following this, South Africa was relatively quick out of the starting blocks as far as motorised transport was concerned. The first Ford to arrive in the country, a 1903 Model A, was in fact the first Ford to be sold outside North America. Cars became more readily available in South Africa with the arrival of the mass-produced Ford Model T, resulting in around 1000 cars a year going onto our local roads by 1910.

As a matter of interest, the Pretoria Lochhead directory for 1913, indicates that some 103 Pretorians either owned a car, a motorcycle or a Taxi-cab. Only the well-to-do could afford such luxury at the time. The white population in Pretoria stood at around 35 000 during 1913, meaning that less than 1% of the population could afford a vehicle then. Local assembly of cars in South Africa began in 1924 when Ford opened a plant in a disused wool shed in Port Elizabeth.

During 1913, South Africa imported 48% of its vehicles from the USA and Canada compared to 40,5% British imports. The US imports increased to 71,5% whilst the British imports decreased to 23% during 1921, confirming the reason for more American vehicles being on South African roads until the late 1940s.

Inscription on the back of the photograph reads: “Mandi in her boys car which she can drive all on her own now. He wants her to get her license”. Probably a 1927 Dodge.

Acknowledgement

Thank you to Brian de Kok and his fellow members of a Johannesburg Vintage Car Club for their assistance in identifying some of the vehicles in the photographs above.

About the author

Carol is passionate about South African Photographica – anything and everything to do with the history of photography. He not only collects anything relating to photography, but also extensively conducts research in this field. He has published a variety of articles on this topic and assisted a publisher and fellow researchers in the field. Of particular interest to Carol are historical South African photographs. He is conducting research on South African based photographers from before 1910. He is also in the process of cataloguing Boer War stereo images produced by a variety of publishers. Carol has one of the largest private photographic collections in South Africa.

Sources

- Johnston, R.H. (1975). Early Motoring in South Africa. Struik. Cape Town.

- Lochhead (1980 reprint). Lochhead’s guide, handbook and directory of Pretoria. State Library. Pretoria

- First Car in South Africa, Wheels24 website.

- Details on historic Motor Cars via the James Hall Transport Museum website.

- Wikipedia entry on Snapshot Photography

- Wikipedia entry for Vernacular Photography

- Kodak and the Rise of Amateur Photography, Met Museum Website.

- History of Photography: The Snapshot, photofocus website.

- The art of the snapshot photograph, Discover digital photography website.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.