Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

In August 2020, a Blue Plaque was unveiled at Swartruggens on the 120th anniversary of the siege of the Elands River Post. It commemorates the remarkable resilience of a small garrison of Australians and Rhodesians during the South African War. General Jan Smuts, who took part on the Boer side, described it thus:

Never in the course of this war did a besieged force endure worse sufferings, but they stood their ground with magnificent courage. All honour to these heroes who in the hour of trial rose nobly to the occasion. (Jan Smuts Memoirs of the Boer War)

Despite the high praise at the time, the episode is often overlooked in latter-day accounts such as Thomas Pakenham’s celebrated book, The Boer War, for example.

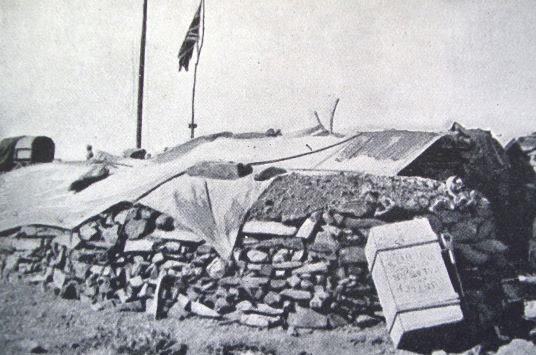

The military cemetery at Elands River (Vincent Carruthers)

The dedication of local history enthusiasts Peet Coetzee, Maarten Stols, John Pennefather and others has ensured that the battlefield is beautifully maintained and the siege is well interpreted in an interesting museum and an excellent book, The Siege of Elands River Battlefield Guide, by Peet Coetzee.

This is the story:

In the early months of the South African War, the British forces suffered a series of defeats that saw them besieged in Ladysmith, Kimberley and Mafeking. However, when the Boers failed to follow up their advantage, the tide of hostilities turned and by June 1900, the capitals of the Boer republics had fallen. Although this offered the illusion of conquest, the British in fact only occupied a few towns, threaded together by long, vulnerable lines of communication. Vast stretches of country remained in Boer hands and the commandos were regrouping into a dangerous guerrilla army.

One tenuous communication link was the road between Pretoria and Mafeking (now Mahikeng). After the relief of Mafeking, small garrisons were posted in the towns of the western Transvaal and by August 1900 hundreds of supply wagons plied the Mafeking road, carrying provisions to these outlying posts and constantly exposed to Boer attack.

Near the confluence of the Elands River and the Doornspruit, (now the town of Swartruggens), the British established a transit post on this dangerous route, and wagon trains assembled there before proceeding further in convoy. On 3 August 1900, the camp was crowded. More than a hundred loaded ox-wagons had arrived, and hundreds of drivers and porters tended the 1500 oxen. In addition, 30 pro-British civilians awaited transportation to Rustenburg. British military strength comprised just over 200 Rhodesians and 300 Australians under the command of Colonel Charles Hore.

That night 2000 burghers under General Koos De la Rey surrounded the camp. Six field guns and three rapid-firing pom-poms were placed on the surrounding hills and the Rustenburg Commando under Commandant Steenkamp crept stealthily along the Elands River, screened by the steep banks. Commandant Potgieter and the Wolmaransstad Commando moved similarly along the Doornspruit.

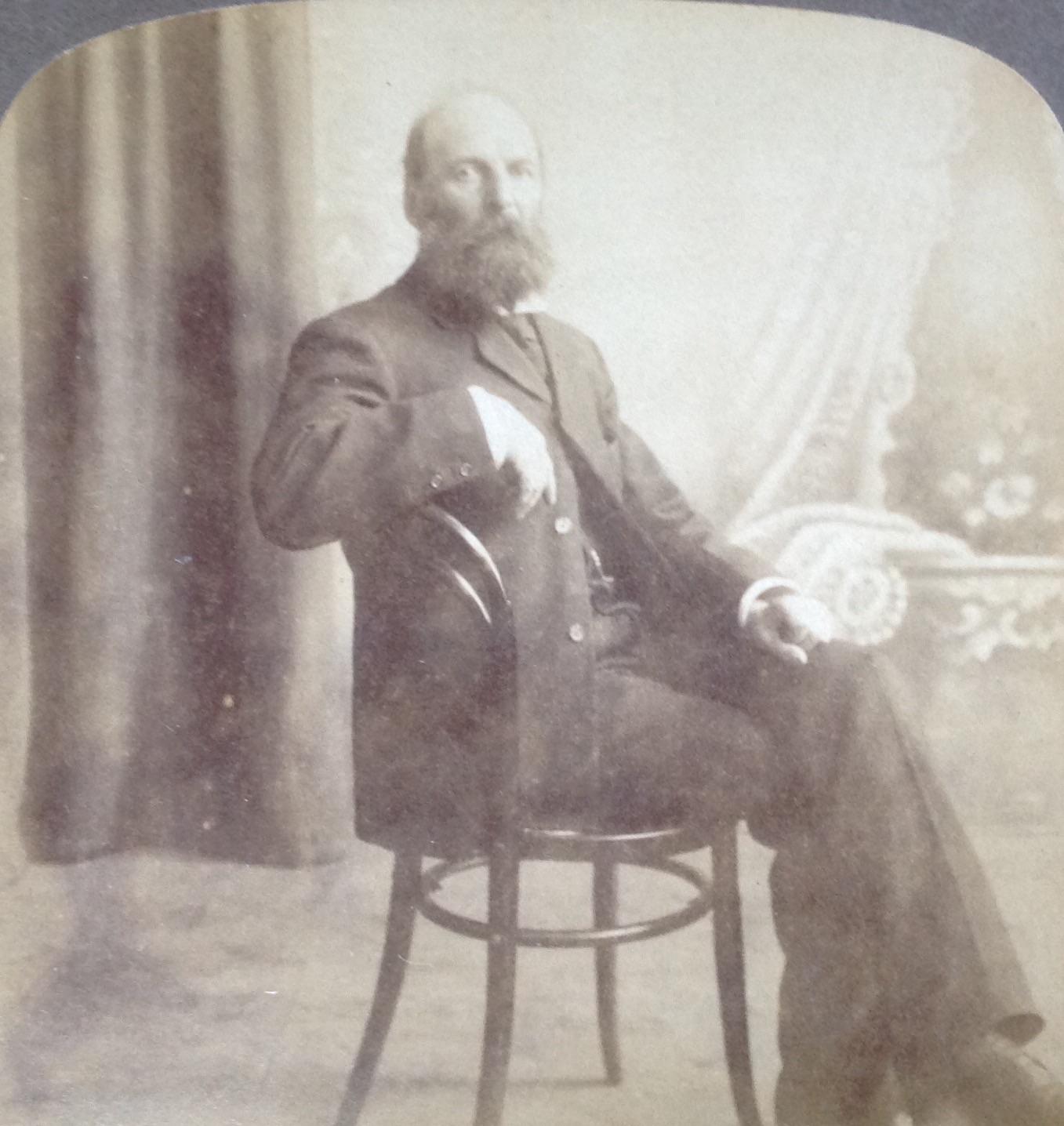

General Koos De la Rey (Hardijzer Photographic Collection)

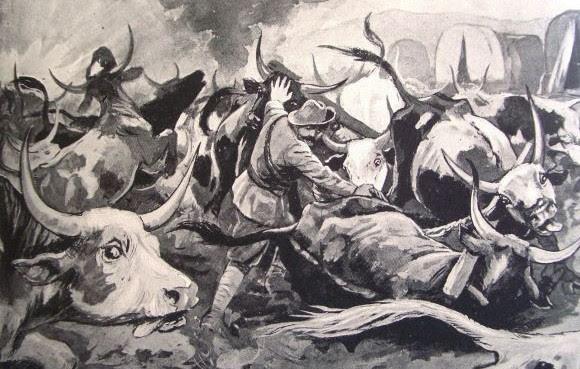

At dawn the Boers opened a relentless artillery barrage that lasted throughout the day. By nightfall 1700 shells had landed in the camp, causing 28 casualties and killing and maiming hundreds of draft animals. That night the men in the camp dug trenches in the stony shale while others undertook the dreadful task of despatching the wounded animals. A makeshift hospital and shelter for the women and children was quickly constructed. When the bombardment resumed the following day, the trenches offered some protection but most of the remaining animals were killed or had to be put down. The only comfort was the knowledge that General Carrington had left Mafeking with a large force several days previously and was expected to arrive at Elands River before long.

Indeed, Carrington’s column did appear the following day but when they were about 3 km away, they overestimated the strength of the Boer force and, to the dismay of the besieged colonials, Carrington ordered a hasty retreat. General Lemmer detached the Marico Commando to pursue the column back to Zeerust and from there the ignoble flight continued all the way to Mafeking.

Soon afterwards, the defenders at Elands River suffered another agonising disappointment. General Robert Baden-Powell, celebrated defender of Mafeking, led a strong relief force from Rustenburg, about 50km away. But soon after leaving the town he heard the fading sound of gunfire from Carrington’s retreat and incorrectly assumed that Hore’s small force had been rescued and was being escorted back to Zeerust. He ventured no closer to confirm his supposition.

The colonial troops were now on their own and their situation seemed so hopeless that De la Rey sent an emissary to Hore commending him on his gallant stand and offering generous terms of surrender. Hore refused the offer.

De la Rey then left the siege in the hands of the Rustenburg and Wolmaransstad commandos and rode westwards to continue re-recruiting Boers who had taken the oath of neutrality and returned to their farms. At Elands River, the intense artillery bombardment diminished but rifle fire continued to harass the defenders by day and night.

Carrington, meanwhile, had explained his shameful retreat by informing Lord Roberts that Hore was outnumbered and must have capitulated. By implication, no assistance was therefore required. On that unsound advice, Roberts ordered the evacuation of Rustenburg and the western Transvaal and turned his attention to pursuing Louis Botha in the east. Completely abandoned, the colonials endured another nine days under heavy Boer fire – thirteen in all – plagued by the stench of a thousand decomposing carcasses and an acute shortage of water.

Fresh water for the camp had to be drawn from the confluence of the Elands River and Doornspruit about a kilometre away. Captain Sandy Butters and Lieutenant Zouch, each with about 75 men, commanded two outposts on the high ground that overlooked the confluence and they supervised nightly patrols to collect water. They had cleared some of the Boers from the riverbeds, but snipers remained under cover and every mission to obtain water ran a gauntlet of lethal rifle fire. Not every sortie was successful, but water was imperative, and casualties were inevitable.

The hospital shelter in the main camp (After Pretoria The Guerrilla War)

On 14 August, ten days after the start of the siege, Lord Roberts finally learned that the Elands River post was still holding out. He signalled his “great distress that Hore should have been so long without help” and called on Generals Carrington, Baden-Powell, Methuen and Hamilton to try to assist before the garrison was forced to surrender. Carrington had fled too far from the scene to be useful; Baden-Powell and Hamilton had left Rustenburg; and Methuen was in hot pursuit of the elusive Christiaan de Wet. So, it was Lord Kitchener who eventually relieved the beleaguered Elands River camp on 16 August and congratulated the garrison for its valour.

Despite the horrors of the siege only five soldiers and four wagon drivers had been killed and are buried in the military cemetery. Fifty other men had been wounded, of whom 11 later died. Most of the casualties had occurred in the first two days before effective defences had been completed. The loss of animals was appalling. Of the 1540 cattle, horses, and mules at the depot on 3 August, only 214 were alive when the siege ended. A special monument near the museum commemorates the animals that suffered.

Despite the losses, this was a proud moment for the Australians and Rhodesians. Colonial troops were often treated with unjustified disdain by British-born officers, but on this occasion, they had not only demonstrated unquestionable ability and courage, they had also been the victims of remarkable incompetence by two ‘professional’ British generals. In Australian history, the siege of Elands River has special resonance because their country was about to be federated into one nation and this provided a grand moment of new national pride. The episode is prominently exhibited in the National War Memorial in Canberra.

Main image: Mercy-killing wounded cattle under bombardment during the siege. (From H.H.Wilson. After Pretoria The Guerrilla War)

About the author: Vincent Carruthers has written several books including The Magaliesberg (four editions), Cradle of Life (2019) and The Wildlife of Southern Africa (three editions). In 2006 he initiated the project to have the Magaliesberg region declared a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve. He has received awards from various institutions including the University of the Witwatersrand Gold Medal in 2016 and the North West University Chancellor’s Medal in 2013. He has been CEO of WESSA, chairman of Birdlife South Africa and member of the North West Parks and Tourism Board. Currently retired from his management consultancy, he is enjoying writing for the Magaliesberg Association for Culture and Heritage.

Sources

- Amery, LS. The Times History of the War in South Africa. Sampson Low, Marston & Co. London, 1907.

- Coetzee, Peet. The Siege of Eland River. Battlefield Guide. Published by the Author. 2019

- Spies, SB and Nattrass, Gail (eds). Jan Smuts Memoirs of the Boer War. Jonathan Ball: Johannesburg, 1994.

- Wilson, H.H. After Pretoria The Guerrilla War. Amalgamated Press:. London, 1902.

- Wulfsohn, Lionel. Rustenburg at War. Published by the Author. 1987.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.