Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

The article below forms part of Mike Alfred's series on Joburg personalities from the first decade of the 21st century. Click here to view Kathy Munro's fantastic introduction and here to view the series index. The stories were written in 2005/6.

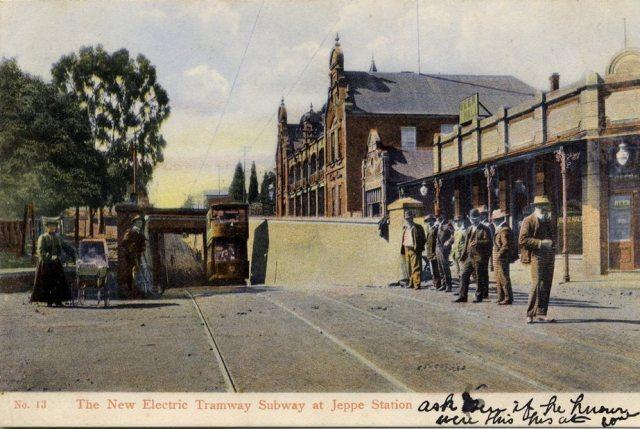

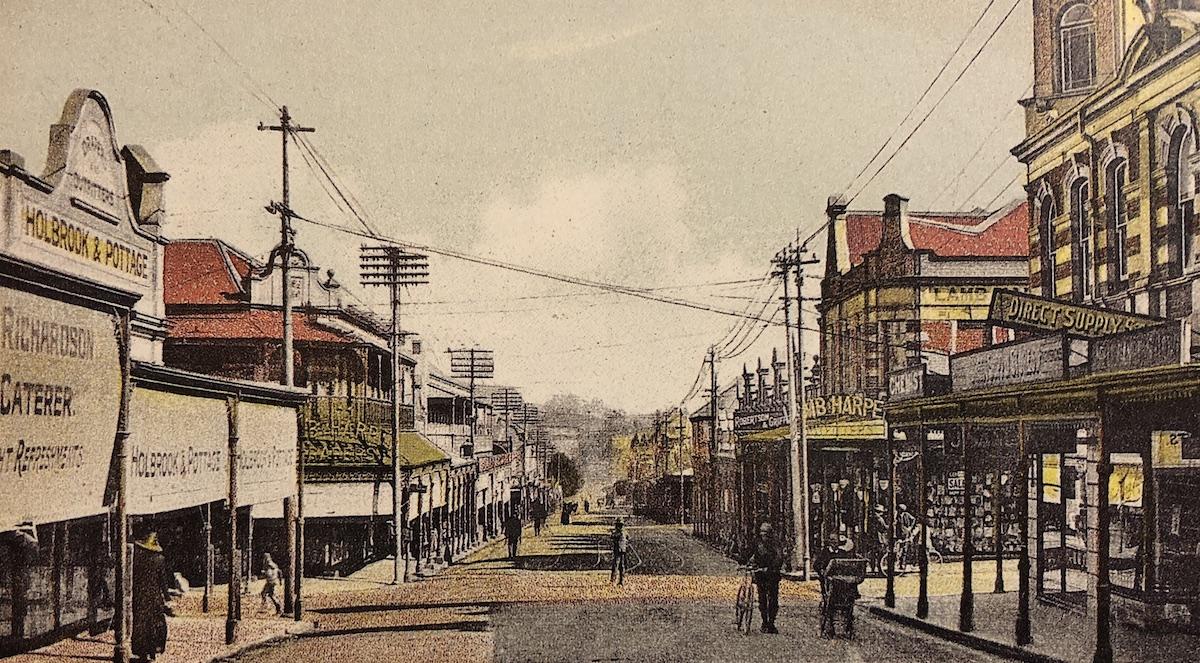

Ravindra [Ravi] Lalla, and his brother Narendra [Naren] started Popular Picture Framers and General Dealers in Main St, Jeppestown, some thirty years ago. From the start, it was successful as a general store and after the later addition of the framing business with its reasonable prices, customers come from far and wide, from all over Johannesburg and surrounds. Visiting this part of the city is an exercise in time travel. Jeppestown with Fordsburg, comprise Johannesburg’s earliest suburbs, established in gold rush days. In the area close to Jeppe Station, renowned for its Art Deco design, Main St, is lined with Victorian buildings housing hardly changed, yesteryear shops. There you will find not only the Lallas’ framing business, but the tailoring business started by Ravi’s dad and continued by his oldest brother. Ravi remembers the trams and electric busses on overhead power lines running up and down Main St. And he recalls a great deal else besides, because in this part of the city he spent his childhood and youth, and he’s worked here all his life.

Old postcard of the Electric Tramway

On a busy Saturday we make our way from the framers through a throng of black shoppers to the quiet of the tailor shop in the next block which is conveniently closed for the morning. We sit on either side of the measuring and cutting counter, the tape recorder between us. Ravi tells me that this is where his father’s independent economic activities began. He points to the surrounding shelves displaying high quality, suiting materials, ‘probably worth a million rand,’ which now, in this time of off-the-shelf, may never be used for their original purpose. Ravi Lalla tells his story:

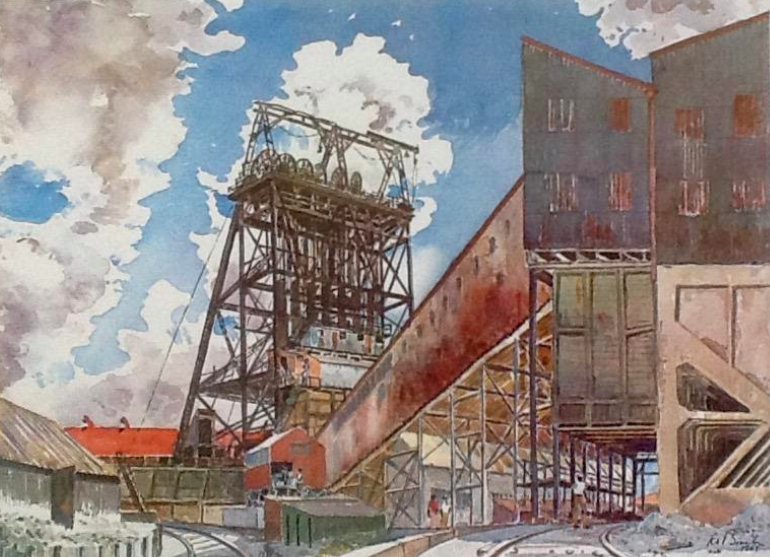

‘My father came here in the late forties, after the war, from the west coast of India, Mumbai side. He came from the village of Dandi where Mohandas Gandhi first opposed the salt tax. My close knit family decided to come to South Africa as a unit. Some of our cousins had a little bit of money from India so they could establish businesses more easily. My dad didn’t have money but he came to work here to establish a better life in South Africa. My cousin started a tailor shop and my dad worked for him. That’s where dad fitted into the pattern. The extended family started in Crown Mines, serving the mining community, the hostels and so forth. Later as families grew, some members moved away from Crown Mines to establish their own businesses and my father and his brother opened a tailor shop here in Jeppestown. I was born in India into a family of two sisters and three brothers, five children. When my dad collected a little bit of money, he decided to call mum and the family over here and we settled ourselves here in Jeppe. I arrived here when I was two, I’m now fifty four, which tells you that my whole life has been spent in Jeppe.

Crown Mines (Birch Collection)

‘We were among the last allowed immigrants. After that, apartheid placed many restrictions on us. For instance, Indians had to have a permit to move from the Transvaal to Natal or the Cape; the Free State wouldn’t allow us at all. But, by the implementation of apartheid laws the Indian families, the community, the Indian culture, grew stronger. We thought and acted together; we used to say, okay, we’ll apply for one joint permit to go to a wedding in Durban or whatever. And we went and came back as a group.

My uncle brought his family in, ten children. It tells you there was no TV there. We lived here, the shop was like this, as you see here, and at the back, we used to live. Because the Group Areas Act didn’t allow us to own houses in Houghton or Killarney or anywhere like that. We worked here, we had to live here, the kids played together, the boys played sport in the street, one street would challenge another, our community was close.

‘My father and my uncle established a tailoring business not far from here in Commissioner St. My late brother and my uncle’s son, the two of them used to sleep in this shop. They had to get into the business actively. Dad wanted somebody to assist. They both worked there after school. That’s where they picked up the business of tailoring, taught by the parents. Dad and my uncle carried on that business for a good ten, fifteen years. That’s when the children were growing, when they were getting educated. I’m proud to say that in my Uncle’s family there are three doctors today. One son today is in Australia, he’s got a huge practice there. He’s got four kids of his own who are doctors and lawyers. We created a family tradition of education, doctors, artisans; in my family there are musicians and so forth. Our parents wove their life around educating the kids first, giving them a good footing.

‘All the kids, all the cousins, we used to go to Gold St, Primary on the corner of Mooi and Durban Streets in City and Suburban. The Coloured Primary school was just across the road. There were a lot of clashes between the Coloureds and the Indians. When it came to break time we exchanged derogatory terms like coolie and bushman, all that type of thing. And it made us stronger. Now everybody lives more peacefully together but I really enjoyed my school life, all that conflict, but nothing too dangerous.

‘At that time there were no established Indian schools, schools which offered Indian culture and our mother tongue. So the community had to establish that. We had our Indian school in the afternoons on the same premises. The Muslim kids went off to the Nugget St, Mosque in the afternoon for their religious instruction. So in the morning we were under the Transvaal Education Department learning in English and in the afternoons they taught us Hindu literature, the Bhagavad Gita, they taught us Gujerati, to write, to read, to do arithmetic in Gujerati. The books and syllabus came from India. The teachers were very versatile. So we were at school twice a day. We knocked off only at about quarter to five. Then we came home and we did our English home work and later in the evening, our Gujerati home work. At the Gujerati school we didn’t have so much of sport but we had a lot of stage shows, we took part in Indian drama. Much of Indian culture was taught with drama. In the ‘English’ school we had our sports day. Always we were in white attire, white shorts, white socks and takkies, white shirts with our rosettes. Our parents had to buy all these things. We were so proud of that sports day. It was held at the Natalspruit Indian Sports ground.

‘We grew up in two worlds. I don’t regret one bit of that life. In fact I’d rather be living that life today. It was the most wonderful life; never mind the hardship and the lesser money. Before going to school each day, the cousins, we all received pocket money from our older brothers at the shop. In those days we had farthings and tickeys, shillings and that sort of thing. They gave us each a tickey. That tickey meant so much to us. We bought so much for so little; sandwiches, cold drinks, toffee sweets, ginger biscuits.

‘Our life didn’t end with school. We had to help at home. In those days we didn’t have electric heaters and so on. Those days we had those big, old, four plate stoves; we had to put wood and coal inside, there was a tank attached to give hot water. That stove kept the two roomed house warm in winter; my mother did all the cooking on those stoves. We had a bathroom, just closed off with a curtain. We boiled bathwater in those four gallon paraffin drums on top of the stove. Coal was freely available in those days. These black guys would deliver bags of coal off the trucks. But we needed wood for starting the fire in the stove.

‘There were a lot of furniture factories around with offcut wood. It was free. We were in competition with our cousins. We waited at the gate, waited for the school bell to ring, so we could race to the furniture factories. The first there at the factory gate got the wood. We also collected the wood in hessian sacks which we piled on our karretjies, which we made out of banana boxes. Some engineering companies gave us bearings for the wheels and the steering. They always wanted to know what these coolies wanted to do with the bearings? I remember those days, my sister, myself we used to take turns to clean the house. We brushed and polished the floor. I could go on and on with all my little memories. We played plenty soccer, plenty cricket, usually on Sundays. I was sport mad. Even today I go to gym at five thirty in the morning, I have my swim, do a little exercise and I’ve taken up bowls as my sport because of my age factor.

‘Let me tell you about this apartheid business. We Indians were shunted from place to place. All the Indians here in Jeppe used to live behind the shop. The business was in front and the house was in the back. But most of the shops were under a white nominee. The business was under a white name and we gave him a fee in order to keep the business running. No Indians were allowed to open up their own businesses, it was strictly for whites. There were signs all over here, you know, Europeans only and that sort of thing. Sometimes you were walking and the Afrikaners would call you coolie, they used to smack you, you couldn’t do anything, you couldn’t raise your hand, nothing. We didn’t say anything we just passed by like the blacks saying my baas! But it made us stronger.

We were shunted from house to house. The boertjies were moving us so much around. The law, the Group Areas Act said all Indians must be out of Joburg, all blacks must be out of Joburg. The black people around here they were harassed by the cops. We saw it. They were arrested and bundled into the vans and sent back to the homelands. With the Indians it wasn’t that harsh. They used to just say, they used to knock at your door, and say, “where’s your permit to stay?’ So we used to show them the permit, granted by the police station. That’s how we used to live. We didn’t know how long we’d be staying in a particular house. The group areas inspector would arrive. “You can’t stay here you must get out!’ We were always moving. We stayed in Madison St when we were young, we shifted to Commissioner St. From there, because the landlord wanted the place, we shifted to Anderson St, corner End. We lived in that yard for many years, staying in the Moslem community. And we hold that Moslem cockney community staying in the yard with us in such high esteem to this day. We shared so much together. They served an ejection order while we were in Anderson St. We came home from school one day, we found all our furniture outside. My cousin arrived from the tailor shop up the road. He said, “don’t worry.” They had a house in Gus St next to the shebeen. And they said, “listen, we’ll make a portion available to you to stay there with your family.” And that’s how they took my dad in. We were so bitter.

In the seventies they offered us homes in Lenasia. This was to be the Indian area for Joburg. They told us to take our pick. My cousins bought some land and started to build. Then my brother got a house for us and we shifted. At first there was nothing. I watched Lenasia growing street by street. I passed my matric at Nirvana High School. My father and brother shuttled from Lenasia to Jeppe every day. They contracted a monthly kombi taxi, my cousins and everybody would travel together. Eventually everybody got out of Jeppe and our lives started growing in Lenasia. Our families started growing in Lenasia. At first the government gave houses. Today you can’t even find a plot of land so people are building another storey on the same plot. All the Indians are still together; the families are together, the culture is very strong. Even though the country is free you won’t find every Indian wanting to settle in Houghton or Greenside. Other parts of Johannesburg are just too rough. Lenasia is green and pleasant; with the opening of the Trade Route Mall, a massive shopping centre, we are self sufficient.

’As for religion, yes in those days our temple was at the Gandhi Hall at 50 Fox St. It was sold to make way for the Hollard St, Stock Exchange and the Gandhi Hall is in Lenasia today. We worshipped there but I must tell you that our Hindu faith is different to the Moslem and other faiths. What I mean by that is that in every Hindu home you find a shrine, a little area demarcated for prayer. You find incense, you find the deities, you find prayers. We channel our energies through the deities. We do the daily prayer or puja. Our religion is centred in the home. Not like the the Muslims, they go several times a day to their mosques. But if it’s a major event, say the birth of Krishna, or Diwali the Festival of Light, then Hindus do go to one of the main temples in Lenasia. In South Africa, I’m glad to say, it’s not like India, here you find the Hindu and the Muslim communities knitted together. That’s what apartheid did for us.

‘Later when the need to look after the families became too heavy for one business, my father and my uncle split and each established his own business. My uncle opened his tailoring shop on the corner of End and Main streets. There’s a delicatessen there today. In 1963 my father and my brother established here at 278a Main St. Although my uncle and my dad had separate businesses the bond was strong, they stayed together in terms of family relations. My brother carried on with this business until last year, July 2005, when his life came to an end as a result of sickness of the heart. Prior to that, he spoke to me saying, “Look Ravi, my health is failing and I need you to take over this business.” So now I’m running both businesses. The pressure is enormous.

‘Popular Picture Framers came about when my younger brother Naren, completed his education. Before that, he worked after school at Transvaal Picture Framers. Money became an issue and we realized, that was my father, my older brother and I, that we must start a business for him. At that point I was a technician working down the road here at Sharp Electronics. We found the premises where the shop stands today, owned by a Jewish guy, he was a Mr Zinn of Zinn’s Furniture, who owned several properties in Jeppe. The previous tenant started a restaurant which failed. We decided to start a general dealer. My neice decided to come in with us, so the two of them started this small general dealer business. That was in 1975 and we found that it was growing and growing. I left Sharp and joined the business. ‘Then we tried various different lines. My father remembered that my brother had experience in framing, so why don’t we start framing? My brother-in-law and my late brother both invested money into the picture framing side and I became the managing partner. It grew and we decided not to give out the work but we employed someone to do the framing in our own workshop in the back. Petros came with his wife Eva and they worked for us for years. The simple framing for the black market grew and then people came to us with photos to be enlarged. We gave that out to someone local here, we didn’t want to buy equipment, but we made a profit and we grew. Our framing became more fancy, more sophisticated, we drew customers from all over, it just snowballed. Today I’d say our customers are 30% white and 50% black. People come because we give a good deal and we’re very helpful. It’s all word of mouth. Although framing is our main business the general dealer remains busy. We sell basic office stationery for small businesses, because there’s no one else around, Cosmetics and watches sell well, also air time contracts in this cell phone age.

‘Take this tailoring now. I haven’t done tailoring for 15, 18 years, my dad taught me the necessary hand skills. But although this sort of tailoring business is dying, we give service, we cater for everything here. I showed you that suit a guy purchased. He came in last night and he wanted it altered because he’s getting married today. So last night I had to get down, I had to take the trouser home. I measured it up and I shortened the trouser. He’ll collect it this morning. So when the push comes to shovel you please the customer.

Will Ravi’s children follow him into the business? He blinks and goes silent for awhile. ‘Didn’t I tell you about my son Atish?’ he asks. ‘This side of my life has become a very sad one. My son had a tragic accident. He’s 24, he graduated BSc, in Computer Science at Unisa. While working for Multichoice about a year and a half ago, driving home near Lenasia on death bend, he rolled his car. He broke his neck and he’s paralysed from his nipples down. Today he’s in a wheel chair at home. It cost me R300 000 for rehabilitation at New Kensington Clinic. His story is so beautiful; mentally he’s so strong it’s carried him through. They made a movie of his life at the rehab centre. Multichoice interviewed him last week, and he’s working there again as a systems analyst. Our family, my daughter my wife, we’ve become closer. My wife works as an accountant in a high profile job but she’s been such a nurse to our son and we’ve come out on top. I must be honest with you. Many times I used to cry, to see such a young boy suffering. [cries] But that’s life, and I pray to God to give us the strength to take care of him.’ Lean, energetic Ravi will need strength and more to keep two businesses going, in order to support his brother’s family as well as his own which includes an ailing mother. Among other problems he has to fight a land claim in India which will necessitate a visit.

‘As for being a South African, I’ve grown to love this country. I love it to bits. I wouldn’t exchange it for any other country. I took my parents to India, I paid for my daughter to travel to India. It was wonderful but they were glad to come home. I’m proud to be a South African. We’ve been through hard times but look what we’ve made.

About the author: Mike has spent most of his life in Johannesburg. He earned his living as a human resources practitioner, first in large companies as a manager, [many stimulating years with AECI] and later in his own small HR consultancy. Much of his later occupational time was spent running training courses for managers on how to handle staff within the framework of South African labour legislation, He wrote and published The Manpower Brief, an IR, HR and sociopolitical newsletter, which was popular in many large companies during the 80s and early 90s. A selection of Briefs were incorporated into the book, People Really Matter published by Knowledge Resources. While working, he wrote several business books, one of which, on negotiating, was a sell-out.

In his ‘retirement,’ he has written extensively about Johannesburg, publishing articles mainly in The Star and Sunday Times. Working with Beryl Porter of Walk & Talk Tours, he developed and guided many walking tours around historic Joburg – Braamfontein, Parktown, Newtown, Centre City, Constitution Hill, Kensington & Troyeville, Fordsburg etc. He regularly took visitors to Soweto. His book Johannesburg Portraits – from Lionel Phillips to Sibongile Khumalo, offered popular biographical essays of well known Joburg citizens. His researched paper on Judge FET Krause who surrendered Johannesburg to Field Marshall Roberts during the Anglo-Boer War, was published in the Johannesburg Heritage Journal. The same journal published his series on famous local paleoanthropologists.

Mike is also a widely published poet. Botsotso recently published his third book of poetry, Poetic Licence. His current historical work, published by co-author Peter Delmar of the Parkview Press, The Johannesburg Explorer Book, takes readers on a journey through old Johannesburg, weaving together a history of events and people, which make this city such a fascinating place. His most recent book, a work of journalism, Twelve plus One, featuring transcribed interviews with Johannesburg poets was issued in 2014.

He lived with his wife Cecily, in a century old, renovated house on Langermann Kop, Kensington. A widower since July 2014, he now lives in Eventide Retirement Village in Muizenberg. He believes himself very fortunate in that his son, daughter in law and grandsons live nearby. His daughter lives in Sydney with her husband and son. In case you’re wondering, Luke Alfred, Mike’s son, is the well-known journalist and author.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.