Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

This article originally appeared in the do.co.mo.mo journal. Thank you to the authors for giving us permission to republish. Click here to view the article as it appeared in do.co.mo.mo journal 48 2013/1.

Aiton Court, in Johannesburg, is a case study in how heritage and economics clash in economically constrained cities. This iconic and formally innovative Modern apartment block from 1937 is located in an area where the income levels of tenants are now very low. Although the building is protected by legislation, the viability of its restoration is being further tested by a rent boycott. The article covers the building’s history, and questions how to approach its conservation differently, given the strong demand for housing at a cost level that would be excluded by purely market–led gentrification. We propose that locating conservation strategies in relation to the building’s history and to other subsidies aimed at the public good may provide other routes to preserving Aiton Court.

Aiton Court’s History

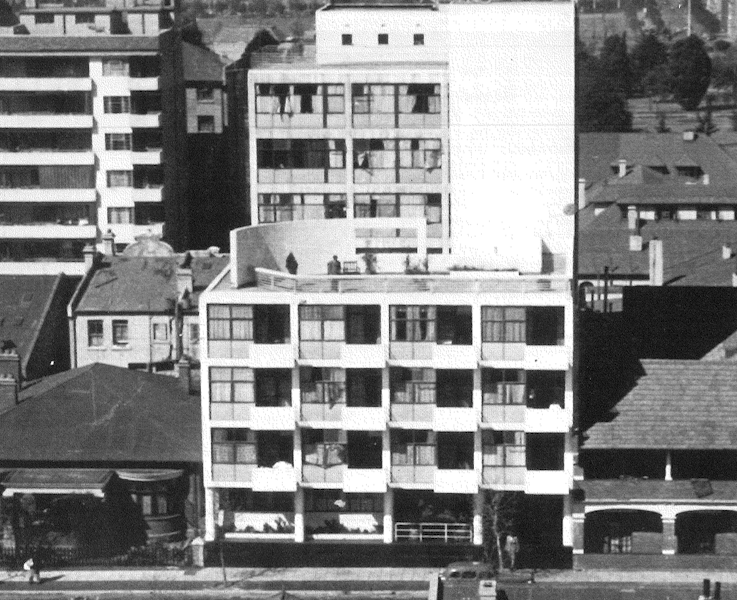

Aiton Court is an iconic and early Modern apartment building in Johannesburg’s dense suburb of Hillbrow [Main image / figure 1]. Designed by young South African architects Angus Stewart and Bernard Cooke in the mid–1930s, it reflects their exposure to the formal language of the CIAM architects through Cooke’s lecturer Rex Martienssen, the leader of what Le Corbusier termed the Groupe Transvaal (Le Corbusier, 1935; Herbert, 1975). The design of minimal apartments also shows the influence of their fellow student and political mentor Kurt Jonas who had studied housing rights in Berlin. Images of this first major work, likewise, circulated within Modern circles, published first in the South African Architectural Record of 1938, and then the Architectural Review, l’Architecture d’Aujourd’hui and The Modern Flat (Yorke and Gibbert, 1948).

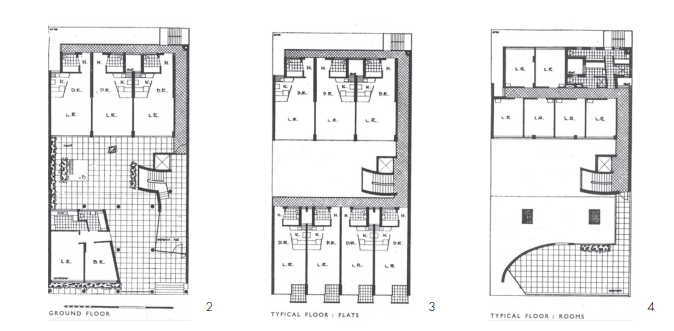

Aiton Court’s compact design fits 40 units on a single, 50x100 foot (15,5 x 31m) property, in two parallel blocks separated by a courtyard, which is overlooked by the glazed stair tower and two access galleries [figures 2, 3, 4]. The roof of the front block is accessible as a solarium. The four and seven storied blocks are orientated north and staggered in height to allow sun into most living rooms. The building typology is transitional between early 20th century rooming houses with courtyards, and the gallery blocks that were to follow after 1945. The top floors contain rooms with shared ablutions and the lower floors have more modern studio apartments with a bathroom and a fitted kitchen area. The caretaker’s flat was positioned at ground floor level to overlook the street and a generous entrance area. The building was well constructed with crisp plastered surfaces, modular steel windows and projecting balconies with steel balustrades, painted largely in white but with an expressive palette in its details [figure 5].

Figure 2: Ground floor plan. Figure 3: First to third floor plan. Figure 4: Fourth floor plan

Figure 5: Street façade, 1937 (Julian Cooke)

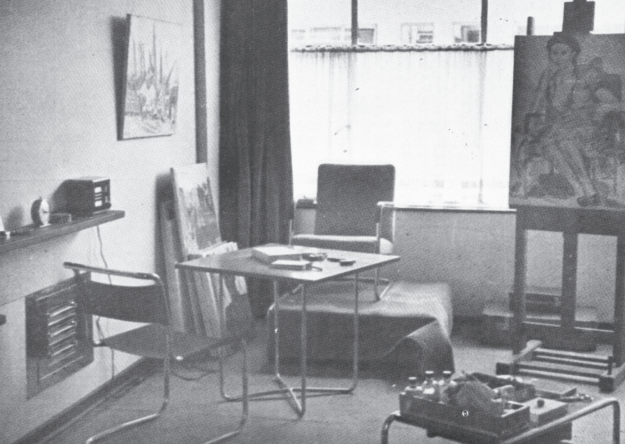

The building was built for commercial rental, so its Modern room norms, services and unelaborated finishes contributed to its relative economy. Nonetheless it was visually and spatially rich and welcoming. The building’s entrance was raised up a half level to a platform edged by the western party wall which was painted a rich green color. The architect Herbert Prins, who lived there in the 1950s, said “It was a beautiful place. You came in through a red pivot door, that was usually open, and there was a fountain in the courtyard” [figure 6]. The rooms and apartments housed young, mainly single tenants, including artists [figure 7]. The only black residents were a few workers who were housed on the top floor of the rear block in small, set back rooms with tiny windows.

Figure 6: Courtyard 1937 (Julian Cooke)

Figure 7: Apartment interior 1937 (South African Architectural Record)

Between the time of construction and the present, the tenant demographics of Aiton Court changed as white middle class tenants left the inner city and poorer African immigrants and former township residents moved in. In the 1980s it was taken over by two tenants of South African Malay descent, who allowed the courtyard to serve as a meeting space for anti–apartheid activities, and for political exiles to stay clandestinely in the apartments. Until their death, the couple, as devout Muslims, managed it from their home in the caretaker’s flat with often charitable intentions, using two apartments for a prayer room and feeding scheme. After passing into their daughter’s possession the building was run remotely, and management problems emerged until, heavily in arrears, it was resold to a large property management company, Trafalgar

Aiton Court in the Present

The purchase of Aiton Court was financed through the Trust for Urban Housing Finance (TUHF), an innovative finance company that provides loans for lower–cost housing projects in South Africa’s inner city areas. Their intention is to finance the renewal of the resource of tens of thousands of residential units in these areas, most of which were built between the 1930s and 1960s. These well located apartments provide a foothold in the city for people who were kept on the urban periphery during the years of urban segregation under apartheid.

The new owners set about painting the balconies red, their corporate color. They were unaware that the building, as a structure over 60 years of age, was protected from change under South Africa’s National Heritage Resources Act (Republic of South Africa, 1999). When the alterations came to their attention, the Provincial Heritage Resources Authority stopped any work on the building until a heritage study and proposal had been approved. Working in partnership with the University of the Witwatersrand, the authors surveyed the building and began to prepare guidelines for restoration.

Figure 8: Street facade 2012

The challenges faced in the repair and conservation of Aiton Court can be broadly defined into the following categories of failure: maintenance, material, detailing and lifespan failure (MacDonald, 1997, 38). The major failures in the building relate to services and structural maintenance. The overcrowding of the building, particularly while hijacked and unregulated, has further stressed an already deteriorating infrastructure and services. This, along with failure of the waterproofing of the trafficable surfaces of the courtyard and solarium and lack of general maintenance, has led to the corrosion of some of the steel in the reinforced concrete causing the spalling of the concrete work which could lead to long term structural deterioration if left unattended. The electrical installation of the building, having reached the end of its serviceable life, is unsafe and requires complete reinstallation.

Beyond these pragmatic needs, the opportunity offered by Aiton Court lies in the fact that, despite the severe neglect of the building, its external appearance has remained largely unchanged. With most surviving inner city contemporaries of Aiton Court similarly neglected or substantially altered, Aiton Court provides an opportunity to become a recognizable example of early Modern Movement in Johannesburg. Subsequently the restoration of the original external Modern color scheme was felt to be essential.

However, for the commercial property owner, explains Trafalgar’s managing director Andrew Schaefer, the heritage value of the building is not of significance. Commercial viability is the motivation for all acquisitions. Schaefer elaborates that properties with perceived heritage value embody a great degree of uncertainty, with undetermined financial outlay and a potential “bottomless pit” of maintenance costs. As incentive for declaration and the conservation of heritage resources the city of Johannesburg currently offers a municipal rates and taxes rebate of up to 20% on declared sites, which is financially insignificant in comparison to the additional costs involved in restoration.

The funding of the restoration is further challenged by the socio–economic context of the tenants and their reactions to longstanding problems with the building. Schaefer explained that when a building is not financially viable, due to low or non–payment of rents, maintenance stops, creating a downward spiral which, in Aiton Court, resulted in the building being “hijacked” by frustrated tenants leaving a legacy of animosity between the new landlord and tenants. Evicting non–paying tenants is not simple, as housing rights and legislation make it necessary for good, alternative accommodation to be found (Tissington, 2011). As a result, Aiton Court’s restoration is caught between two logics, that of social housing rights and that of market–driven gentrification.

Breaking the Deadlock

This research has pinpointed the tensions between tenant and landlord rights as the cause of Aiton Court’s ongoing deterioration. Despite its obvious global significance as an iconic Modern design, and its important local history, the resources available to support heritage restorations are insufficient to stop its decay and restore it. Raising rental income through gentrification, which would involve the eviction of existing tenants, is legally difficult and morally inappropriate. As a way of breaking this deadlock, it proposes that the conservation methodology expands to consider issues beyond its physical condition, to locate it in its history of use, its urban context, and a broader landscape of public subsidies. This research will in turn inform a strategy of critical conservation that proposes realistic and incremental renewals that do not exclude the possibility of a full restoration.

Three Contexts beyond Conservation

The first context is the historical record. Researching the building’s use across history, especially through oral narratives, allows insights into those times at which the building worked well. At the outset, it was successful in drawing innovative tenants who appreciated the physical support of well serviced, affordable apartments, and their visual qualities. The cultural capital represented by the design may again be rewarded by a high quality restoration, but at the moment, the urban context and its rental levels deny this option.

However, the physical qualities of the public areas, the flow between public and private realms and the potentially attractive courtyard, as well as the social benefit offered by these spaces, can be restored at a lower cost. History also suggests that the tenant–centered location of the caretaker’s flat supports better management. A trained, socially responsive caretaker could manage a social housing component in the upper floor rooms that could access further rental subsidies. Finally, the combination of such cheaper, communally serviced rooms and more independent apartments allows for tenants to move between these two housing options depending on their economic situation, so ensuring a longer stay within the same building and its community [figure 9].

Figure 9: Stair tower 2012

The second context is the building’s precinct, the Ekhaya Neighbourhood, which is an award–winning, socially driven neighborhood renewal project (The Housing Development Agency 2012). In its present state, Aiton Court brings down the appearance of the area and makes the adjacent buildings less attractive to tenants. The potential for its renovation to support this neighborhood improvement lies in the close physical relationship between the front apartments, roof terrace, entrance lobby and caretaker’s flat and the street. If this set of relationships could be restored then the precinct as a whole would benefit.

The third context regards the funding sources and subsidies that may exist as an alternative to the small heritage rebates on offer. These include a tax rebate on building improvements in the inner city (The National Treasury, 2004), and a contribution by the Johannesburg Development Agency of up to 70% of the capital costs of public space upgrade. The case needs to be made that the nominally private, but street–oriented spaces of Aiton Court would substantially improve the public realm.

Lastly, the carbon savings represented by the restoration of the building may qualify it for support by the Green Fund, a national initiative “that seeks to support green initiatives to assist South Africa’s transition to a low carbon, resource efficient and climate resilient development path delivering high impact economic, environmental and social benefits” (Development Bank of South Africa, 2013). This funding could be applied in research and reinstating the many plants that the original design included, and so become a capacity–building showcase for inner city greening. It could also restore the front windows, replacing them with solar–responsive double glazing that would alleviate the daytime use of curtains and reinstate relationships between residents and the street.

Critical Conservation

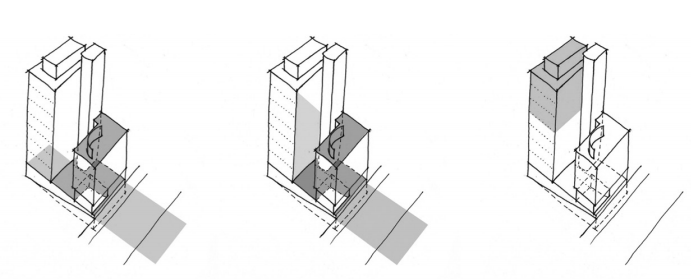

Critical conservation is a strategy that imagines a staged renewal of a building that mediates between a realistic approach to what is possible and the ideal of total restoration, without stopping the possibility of such a return. The immediate needs in Aiton Court are for the restoration of basic services, and the protection of the envelope. But beyond this, the staging of restoration could be planned strategically, to take advantage of alternative subsidies to those available for heritage buildings. The impact of the three strategies is illustrated in drawings that show the areas of the building that could be dealt with through three stages of restoration that might qualify for other areas of potential funding. The first image considers spaces in and beyond the building envelope that could be considered, and so renovated, as part of the public realm. The second image locates potential green surfaces that could be renovated via the Green Fund. The final image identifies the area of the building that could be managed as social housing for lower–income residents, so creating continuity in the tenant body and avoiding evictions [figure 10].

Figure 10: Spatial strategies for renewal: the location of public spaces, green elements and social housing. Mayat Hart Architects, Johannesburg

Conclusion

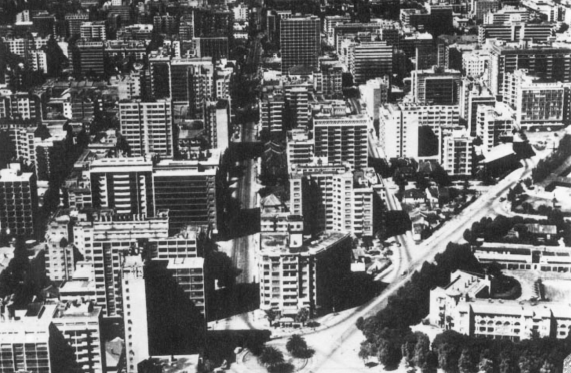

Although this is a single case study, many more inner city buildings, most less iconic but nonetheless valuable assets, are caught between economics and heritage [figure 11]. Getting Aiton Court’s restoration right will have an impact on all of them. The interlinked issues around Aiton Court need not be antagonistic and ultimately destructive. Low–income tenants and this heritage building could, with sufficient research and alignment with existing funding initiatives, once again become compatible.

Figure 11: Hillbrow, Johannesburg, ca. 1960. Photo from Davids

This achievement, by balancing social and physical environments would be in tune with the original ideologies behind Modern architecture. Towards this, conservation needs to be relocated into a broader but more nuanced public discussion, taking into account affordability, sustainability, history and incremental change.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.