Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

The William Cullen Library is a much loved landmark on Wits University's East Campus. It was built in 1934 on the west side of the Library Lawns and houses a vast number of valuable collections. The article below, compiled by Rowallan Hugh Fitchett, traces the architectural history of the building. It was originally published in a mid1990s edition of Between the Chains, the journal of the Johannesburg Historical Foundation.

The William Cullen Library on the east campus of the University of the Witwatersrand is almost certainly the building most appreciated by members of the academic staff. I have heard this opinion on numerous occasions from lecturers and students in a wide range of disciplines, outside as well as within the Faculty of Architecture.

My own interest in the building was stimulated first by architectural form, which appealed to me above all other buildings on campus when I registered as a postgraduate student in 1979. This interest was heightened in 1981 when my future wife informed me that it was the first building designed in this country by her grandfather, William George Whyte at the age of 25 after emigrating from Scotland. My interest was accentuated from 1987 onwards on account of the material contained in the library. I spent months if not years in transcribing material from irreplaceable 17th and 18th century volumes which (correctly) were not permitted to be photocopied. My association with the library is thus an intimate one, architecturally and academically.

The architectural history of the William Cullen Library begins with a fire which started in the early hours of the 24th December 1931 in Central Block (the first building of the University and still its focus). The fire caused extensive damage to the building, part of which collapsed entirely. This part, located behind the front wing, was a temporary structure built of timber and iron, as the Council of the University had not considered it necessary to use fire-resistant materials. The library had been located on the top floor of this inflammable structure, and its contents were thus entirely destroyed.

The original design for Central Block had included a domed and triple-volumed octagonal library as a central feature behind the entrance portico. However, this proposal had been rejected on the grounds that the silence in the library would have been compromised by the noise of the surrounding activities, and because it would not accommodate future expansion. The first reason is not convincing, as soundproofing methods were available in the 1920s. The second is equally questionable, as branch libraries were later to appear in different Faculties to accommodate the needs of an expanding student body. It is more probable that the costs involved were the major contributory factor in the decision to eliminate a permanent library from the first design of Central Block, with the concomitant (and probably greater) expenditure of replacing the entire contents of the library after the fire.

Ironically, the necessity for a permanent library had already been acknowledged by 1928, when a model was constructed to show the future development of the campus. One of the buildings in this model (no longer extant) was a library corresponding in location and general form with the building under discussion. The Council of the University had decided by 1930 to proceed with this project, but its appeal to the Government for a loan of £50 000 was turned down.

However, the necessity for building a new library (and of obtaining the books which it was to house) became unavoidable after the fire. Two architectural firms were commissioned to collaborate on the design. They were Emley and Williamson, in association with Cowin and Powers. The drawings were completed within a year and tenders were received at the end of 1932.

The lowest of these was from John Barrow, who was awarded the contract. He had in fact submitted two tenders, reflecting the discrimination prevalent in the 'pre-Apartheid' era. The lower was for £42 800, using 'African' labour, and the higher was for £45 600, using 'white' labour. The Council accepted the lower figure, but appealed to the Department of Labour for the shortfall to reach the higher figure. This was granted on account of the high level of 'white' unemployment in the years of the Depression.

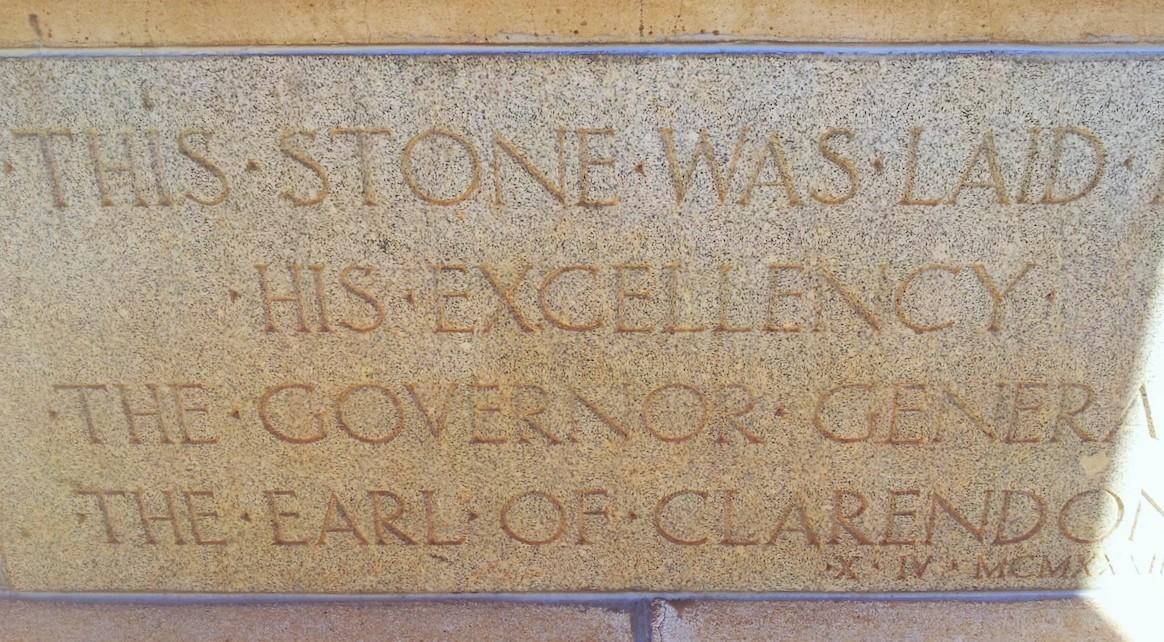

The foundation stone was laid on the 10th April 1933 by the Governor-General, the Earl of Clarendon, and the library was opened by Prince George, Duke of Kent, on the 12th March 1934. The total cost of the building, including its interior fittings was £55 000.

William Cullen Library Foundation Stone (The Heritage Portal)

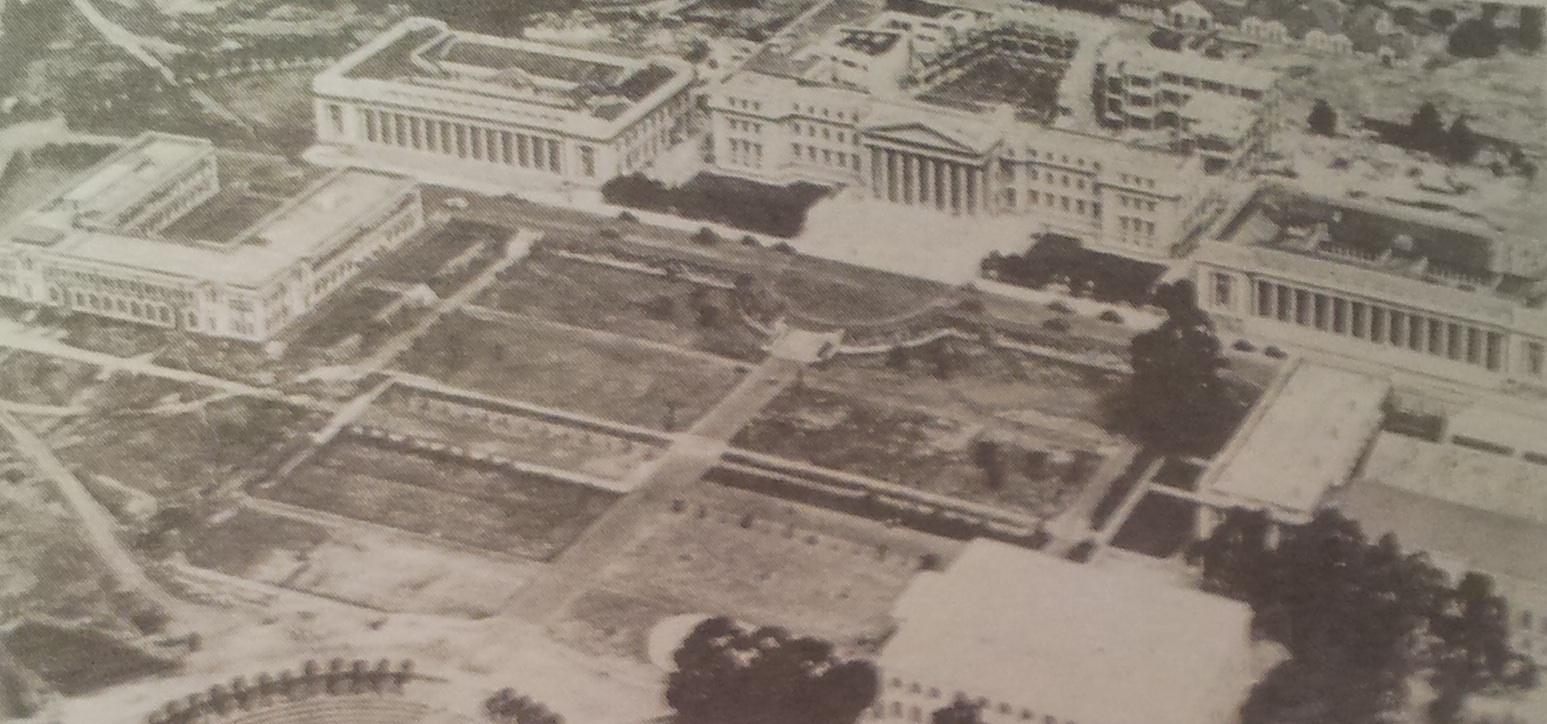

By this time a number of other University buildings had been erected (see image below). The first three were along the road (now closed) crossing the campus from east to west. These comprised Central Block, which was set back from the Physics and Engineering buildings flanking it on either side. Central Block had a portico in the Corinthian order, whereas the flanking buildings used the less elaborate Tuscan order for their columns.

Siting of the William Cullen Library

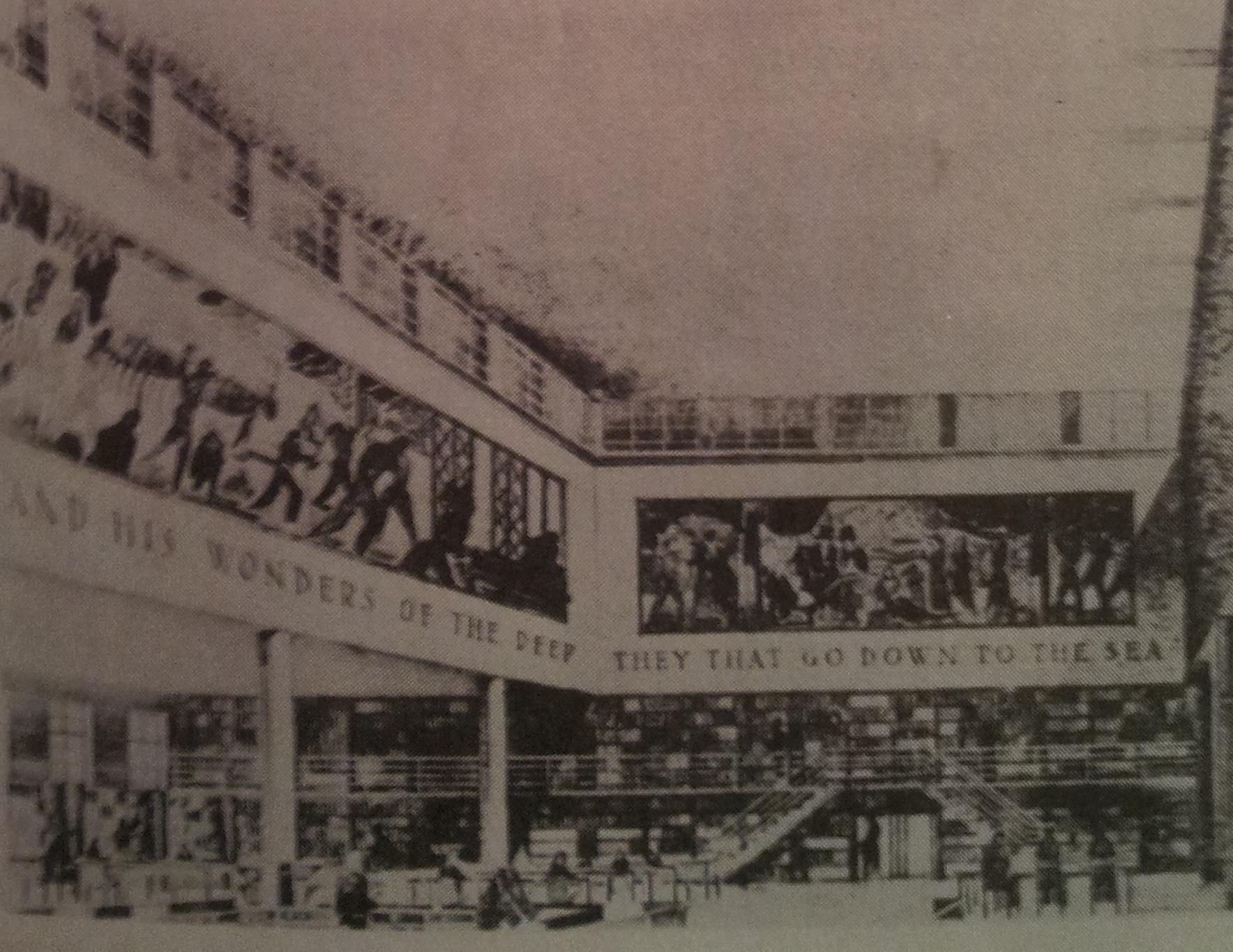

To the north were the Engineering laboratory (on the east) and the Biology block (on the west), set back from the inner edges of the two buildings flanking Central Block, and facing each other across the wide open space in front. This formal and symmetrical composition was concluded by the swimming pool further to the north, with its central amphitheatre and flanking towers, thus establishing a formal axis towards the portico of Central Block.

The William Cullen Library was sited to the north of the Engineering laboratory, and was set forward from it, thereby aligning with the inner edge of the earlier Engineering building flanking Central Block. The intention was almost certainly to erect an equivalent building across the open space (the present Library Lawns), thus establishing a cross-axis. If this had been implemented, the cross-axis would have been marked by projecting buildings, in comparison with the recessed Central Block on the principal axis. This plan was not realised, however, and the library therefore derives its impact solely from its individual architectural form without the assistance of an overall siting arrangement for Library Lawns.

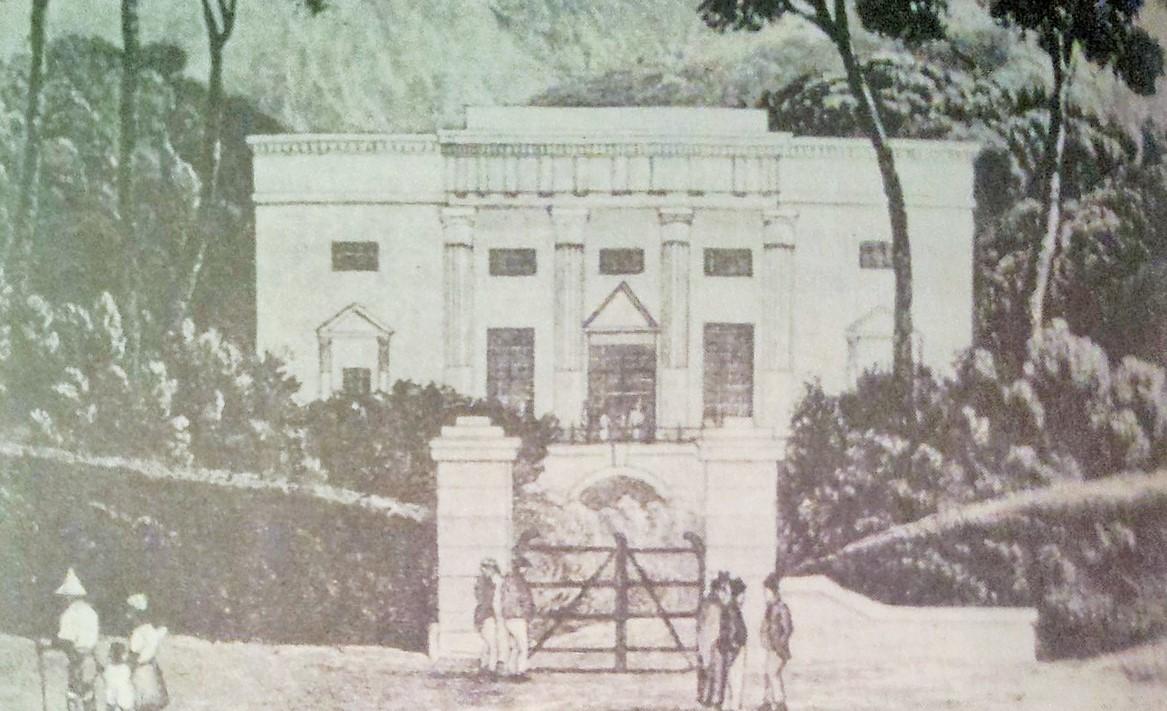

As an individual structure, the William Cullen Library is most notable for the fact that it is one of only two buildings in South Africa inspired by the Petit Trianon in the gardens of Versailles, designed by Ange-Jacques Gabriel in 1763. The first was the house Papenboom (otherwise known as The Brewery) built at Newlands on the Cape Peninsula by Louis-Michel Thibault between 1783 and 1786, but no longer extant. Thibault had been a student of Gabriel at the Royal Academy of Architecture in Paris, and is the best known architect of late 18th and early 19th century architecture at the Cape.

Papenboom, Newlands

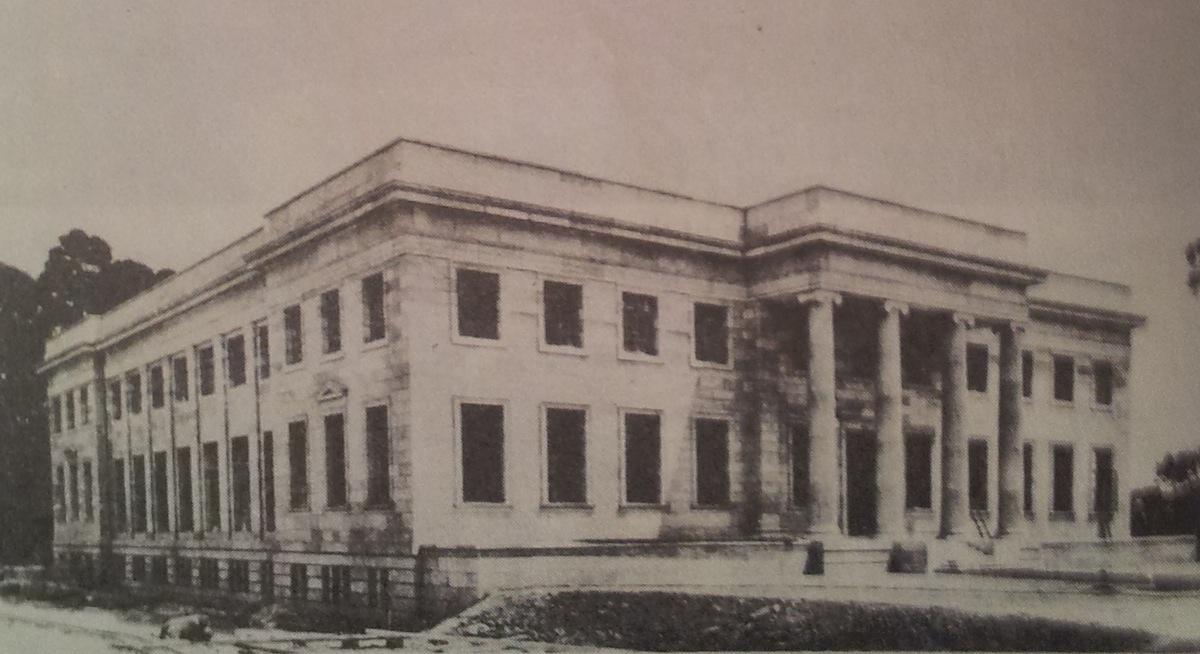

Thibault's Papenboom was a far closer copy of the Petit Trianon than was the William Cullen Library, which used its precedent in a less derivative manner. The portico of the library projects further from the facade, and there are four windows on either side instead of the one in Gabriel's and Thibault's buildings. Moreover, the parapet on the roof is solid, in comparison with the open balustrade of the Petit Trianon. Nevertheless, the inspiration for the design of the library Gabriel's Petit Trianon, as stated in the communication to my wife by William George Whyte, the architect entrusted with the design.

Exterior of William Cullen Library

Having established the provenance of the design for the Library, its architectural characteristics can now be examined. The exterior of the building is articulated by a projecting entrance portico, and with lesser projections on the sides corresponding with the front and rear ranges of rooms. These side projections are emphasised by triangular pediments over their ground floor windows, but the entrance portico had no pediment. This omission was probably intentional, in order to avoid competition with Central Block, the only pedimented building on the University campus.

The four columns supporting the portico are Ionic, thereby complementing the Corinthian and Tuscan orders of the Central Block and its flanking buildings. On either side of the portico are four windows on two storeys, those on the ground floor being considerably taller than those on the upper level, which are located directly beneath the triple-fascia architrave of the Ionic entablature.

The portico gives access to a square entrance hall containing two columns, which are aligned with the outer walls of two passages at the rear, leading to staircases on either side. These passages are reached through double doors with fanlights above, extending to the full height of the ceiling and thus establishing a strong cross-axis. Between the two columns, on the entrance axis, is the door to the main reading room.

The central area of the main reading room is the most notable space in the William Cullen Library. It is double-volumed, lit from above by clerestorey windows, and flanked to left and right by single-volumed spaces. These are separated from the central space by two slender piers, which support the walls of the upper volume on either side. Two of these walls contain large paintings of South African colonial history, and another has recently been commissioned for the third wall, to the right.

The Main Reading Room

The interior arrangement of the main reading room commenced with the librarians' enclosure to the left of the entrance (with a private staircase down to the stacks), balanced by an arrangement of shelving and catalogue cabinets to the right. Beyond this, the furniture layout was asymmetrical, with tables of different sizes to the left and right. However, the seating arrangements under the single-volumed flanking spaces were identical, although facing in opposite directions. This was to ensure that each reader received light from the left-hand side, and the likelihood of glare was diminished by the provision of built-in bookshelves at right angles to the walls between the windows.

The central axis is terminated by a door beneath the two lateral staircases which give access to the upper gallery of shelving. This door leads to an anteroom which opened on to a staff reading room to the left, a workroom to the right, and a service staircase ahead.

Returning to the passages opening off the entrance hall, these lead past two large rooms, the one to the right having contained the Gubbins Collection and the one to the left having served as the senior students' common room. Beyond these are two staircases, one on either side, leading to the upper floor. This had an exhibition room as its focus in the centre, behind the portico, flanked by a room for special collections to the left and staff rooms to the right.

The upper floor corridor continues around the blank walls of the double volume of the central part of the main reading room. These walls are used at present to display some of the library's collection of pictorial Africana. Three seminar rooms were located to the left and right of this central volume. Another two seminar rooms flanked the service stair behind, with offices beyond on either side.

The basements contained the stacks. The bookshelves took up the bulk of the area, with small study rooms located along the sides next to the windows. The rear part of this level, on either side of the service staircase, was taken up by service activities such as book-binding and photography. These lower levels have piers at much closer intervals than those in the main reading room, owing to the loads generated by the weight of the books.

The description outlined above is based on the drawings published in the South African Architectural Record in 1934. However, not much has changed since then apart from re-arrangements of furniture and re-allocation of rooms. The common rooms and seminar rooms have all given way to additional accommodation for books, but the study rooms in the basements still exist, and are used for specialised purposes such as microfilm readers. The stack rooms, moreover, have been given over to periodicals, as the books that used to be housed there are now accommodated in the Wartenweiler and other libraries of the University.

The William Cullen Library has thus become largely a research library, characterised by the quiet concentration of the serious students and staff members who make use of its resources. This is perhaps appropriate for a building which presents an appearance of Classical dignity to the outside observer.

Once inside, however, the building is transformed into the architectural language of the 1930s in which it was built. Its planning, its spatial conception and its detailing realise this language far more successfully and far less aggressively than many of the outwardly modern buildings erected during this seminal period in the development of 20th century architecture in South Africa.

The William Cullen Library is the essence of good architecture. It acknowledges its physical setting in terms of its exterior, but does not ignore its place in the modern world in terms of its interior. It must remain as it is, without alteration.

References

- Murray, B. Wits; The Early Years. (Johannesburg; Witwatersrand University Press, 1982).

- Pearse, G. E. The Library: University if the Witwatersrand.

- The South African Architectural Record, Vol 19, No 4, April 1934

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.