Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

This remarkable story of Fanny Klenerman and the Vanguard Bookshop first appeared in the journal Jewish Affairs in 2017. Click here to download the original article which includes full notes.

A lifelong rebel, a trade unionist and a Trotskyite, Fanny Klenerman’s name is chiefly associated with the Vanguard Bookshop, iconic of leftist circles in Johannesburg during the period 1931-1974. Although her shop is often cited, most recently by Mark Gevisser in his autobiography, Lost and Found in Johannesburg (Jonathan Ball, 2014), its history has never been told, while its eccentric owner has been largely forgotten.

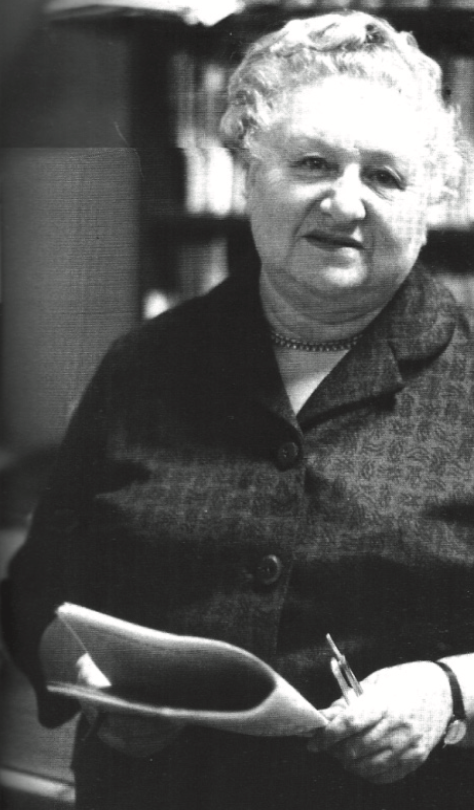

Fanny Klenerman, founder and director of the Vanguard Bookshop, Johannesburg (via Jewish Affairs)

In 1982, Fanny dictated her story to Ruth Sack, who recorded it on to audiotape and subsequently transcribed it. At that stage Fanny was virtually blind and unable to read or write her memoirs independently. In 1988, the tapes, the transcription, and a collection of pamphlets were donated to the Department of Historical Papers at Wits University by Rose Zvi, a South African novelist now living in Sydney, Australia. Zvi, who had met her in her shop, arranged for Ruth Sack to record her story. On the basis of her memoir, this article will attempt to reconstruct the story of Fanny Klenerman’s life and the history of the famous Vanguard Bookshop, so that they can assume their rightful place in the history of the Left in Johannesburg.

Fanny opens her memoir with the description of an incident for which she became notorious, namely when she and seven girl friends were arrested for bathing nude in a secluded remote mountain pool near Witpootjie in the Transvaal! The women were taken to the police station, fingerprinted, and only released on the payment of a bail of £500 that they managed to raise with the help of businessman, Fred Cohen, and trade unionist, Solly Sachs. However the incident made headlines in the newspapers. All their names and addresses were published as well as the fact that Fanny was the owner of the Vanguard bookshop.

On sentencing them to a fine of £2 each the magistrate declared that society had done its utmost to instil in them a sense of propriety. They had built public lavatories in the veld for Africans “to prevent them defiling the soil of the veld and here ... [they] Europeans, students and intellectuals furthermore [were] indulging in disgusting practices.”

Fanny succeeded in having the verdict overturned and the fine revoked on the grounds that the place where they had bathed was remote and inaccessible and could hardly be considered to be in the public eye. In order to substantiate her claim, her attorney had the place inspected by a group consisting of the magistrate, the press and various other officials. As none of them were familiar with the secret hiking trail, they managed, with great difficulty, to get only half way down. It transpired that the police who had arrested the girls had spied on them through binoculars from an adjacent ledge. Fanny was disgusted by the narrowness of officialdom in South Africa, pointing out that nude bathing was commonplace in Europe. She and her friends continued to bathe nude in mountain pools, “observed only by monkeys and baboons”.

Many felt that this incident would harm Fanny’s business. However, ever true to her beliefs, she had no regrets. In her words: “I have always tried to maintain my true opinion against those obscurantists and conservatives. And so far, people of intelligence have accepted me. They regard me as a well-meaning rebel, but certainly not immoral ... [Our] real customers – who also became friends – all respected me as the owner of the best bookshop in South Africa”.

Childhood years

Born in 1897 in Lutzin in the Vitebsk Province in Belarus (today Ludza, Latgale Province, Latvia), Fanny Klenerman immigrated to South Africa at the age of four or five together with her mother and older brother. They joined her father, who had arrived in Johannesburg in the late 1890s. With money scarce during the period of the South African War (1899-1902), Fanny’s mother operated a small store or ‘kremelke’, selling herrings, kvas (a popular drink made from the juice of fermented bread), pickles and brown bread. After the war the family moved to Kimberley, where Fanny’s father opened a men’s outfitting store. Self-educated and an accomplished Hebrew scholar who read very widely, he lost his religion but not his Jewish identity. Although they never belonged to a synagogue, Fanny’s mother insisted that the family attend services on the High Holidays so that the children should not “grow up to be savages.” The family supported Jewish organisations but were not Zionists.

Theirs was a Yiddish-speaking household. Fanny remembers first attending school in Kimberley not knowing a word of English, but she soon picked it up and by the age of seven or eight was an avid reader. At the age of eight Fanny became a vegetarian, having witnessed the killing of a chicken taken to be slaughtered according to Jewish law. She never again ate meat although as an adult she did eat fish for reasons of health.

She was first exposed to socialist ideas by her father, who imported The Clarion and other liberal and socialist newspapers from Britain. He and his friends were dedicated to socialism and to changing society and discussed these matters with Fanny. By the age of fifteen, Fanny was an accomplished public speaker and was invited to speak at the Zionist Hall on Sunday nights. She was also a great admirer of Voltaire and joined a group of Rationalists who met in Kimberley. At the University of Cape Town, where she graduated with a degree in English and History, she was a prominent speaker in the Students’ Parliament and her interest in socialism was encouraged by reading the New York Socialist weekly The New Age.

University of Cape Town (Don Shaw)

After graduating, Fanny taught at Wynberg Girls School but found the atmosphere “stuffy and repressive.” She returned to Kimberley, where she was unable to find work because of her outspoken political views, expressed in letters to the local newspapers. Shortly after the Rand Revolt in 1922, relying on her father’s connections, she left to work for the Labour Party in Johannesburg. Within a year she broke with the Party, objecting to its industrial colour bar. Many years later she recalled: “Here we’ve come to a country the British stole from the Africans ... They haven’t got money to go anywhere, and you’re excluding them from society and bringing them down to the level of serfs. And I said ‘I can’t take it’”.

Fanny joined the Communist Party of South Africa (CPSA), the only multi-racial party. Together with her great friend, Eva Green, she would distribute Umsebenzi (The Worker) newspaper in Rooiyard, Soweto, every Friday afternoon. Fanny was only a member for a short time. In 1935, together with four others, including Eddie Roux, she was expelled for being critical of the party’s policy.

On leaving the CPSA, Fanny joined the South African Workers’ Party. Inspired by the literature of Leon Trotsky, this had been founded by the Lenin Club in Cape Town in 1935. A branch was established in Johannesburg that had a small membership but was very active. The Party was born out of disgust over Comintern policy, but said Fanny, people were not sufficiently politically aware to understand the differences between them and the Communists. She defined their objectives as “to organise the workers, to accept change in society, and to resist the Communist alternative.” The members of the group were professional people, doctors, students and intellectuals. Because of the structure of South African society, where the workers were mostly black, they had little contact with working people and so could not influence them. The fact that none of these groups survived, says Fanny, was sufficient indication that there could be no such thing as a ‘workers group’ of intellectuals.

South African Women Workers’ Union

While working for the Labour Party, Fanny decided to enrol for legal studies in the extramural program at Wits University. She continued for two years, until she realised that these courses would not assist her in her chosen work, which was to organise working class women who lacked any means of safeguarding their positions as workers. After the 1922 Strike, wages fell sharply and there was a large movement of women from the country into the city where poverty was rife. The average monthly wage for working women was £7, a salary on which it was impossible to survive. Following the strike, the trade union movement was in chaos and Fanny determined to do something about this.

Wits University (The Heritage Portal)

Together with Eva Green (like herself, a teacher, humanist and socialist), she determined to form a union, and thus the South African Women Workers’ Union (SAWWU) came into being. The work was difficult as they had no form of transport, and took trams where possible to factory yards. They spoke to the women on their breaks, often in the face of strong resistance from the factory owners, who on occasion threatened to set their dogs on them should they return. Fanny managed to gain ground in some smaller factories and in addition was supported by the owner of Rondi’s, a large factory, whose Italian owner, Mr Rondi, a socialist, was not averse to enrolling his workers in a trade union.

They explained to the women their rights as workers, the wages due to them, the morning breaks they should be granted and the paid holidays to which they were entitled. The main aim was to raise their wages. Factory owners reacted in two ways. The more pleasant agreed but felt that they just couldn’t afford such wages while others simply refused to allow their workers to join a trade union. In such a case they would advise the women that if they could not achieve anything individually they must achieve it en masse.

Men’s wages tended to be better than that of the women’s and in several cases the men opposed the idea of a women’s union fearing that their wages would be reduced to allow for the raising of wages for women. Fanny assured them that if this occurred they were free to apply to the Wage Board. More and more women joined the Union, particularly from Rondi’s factory, and they made application to the Wage Board. As a result, women’s wages were upscaled, a new scale introduced, and workers were graded. This gave the SAWWU a great boost. Shop stewards were appointed to enrol members and to collect fees and the Union flourished.

As a trade union official, Fanny earned £17 a month, a very small amount. She shared a flat in Doornfontein with two friends, thus managing to live reasonably comfortably. They entertained friends and members in the living-cum-dining room where they also invited people to address their meetings. They would visit the women at their residences, where they were often sharing four to a room and living and cooking cooperatively.

Their work was universally praised. Eva, being a teacher, had to work quietly and surreptitiously and could not take an official position in the union. She would come after school and do whatever was needed - typing or recovering back pay or holiday pay from employers and sometimes threatening to sue. On occasion they would have to invoke the Labour Bureau, who would take on cases where the proper wages were not being paid. This Union continued for a few years until it was absorbed by a larger Union.

Fanny says about this period of her life:

During the course of my life, I have been associated with very many occupations, some more interesting than others. But speaking generally, I devoted myself to causes which were close to my interests. Frequently working with organisations, I became enlightened about how politics worked, and I grew disillusioned and also very sad that most of my ideals were not only not current in our society but impossible to be introduced into this capitalist system of exploitation and expression of greed and restriction of ideas.

The ICU and Night Schools

Fanny worked in the Industrial and Commercial Workers’ Unions (ICU), not as a paid official but as a teacher of English to Africans who had not had any education. It was a difficult task. She had to use her own initiative to devise her own system. There was a night school for those who had already attended school and had a rudimentary knowledge of the English language; and a school with various classes, such as rudimentary arithmetic, for those who had had no education whatsoever. Fanny did everything in her power to enrich the experience of her students. Although refused entry to the Johannesburg Art Gallery, as it was “For whites only”, on one occasion she managed to gain entry for her students to the Johannesburg Observatory.

Johannesburg Art Gallery (The Heritage Portal)

Because of the Pass system Africans were not allowed to be in Johannesburg beyond a certain hour. One Friday, one of her pupils was arrested and kept in jail over the weekend. Distressed Fanny went to the courts to explain that her pupils worked and had no way of attending classes during the day time. The official obliged by providing her with a note that her pupils could carry indicating that they were studying at the ICU School and that they were allowed to be in the city for extended hours to allow them time to get home.

Fanny attributed the ultimate failure of the ICU to lack of control over money. Too many people had their hands in the till. When the Trade Union Council in London sent out a supervisor, one W. C. Ballinger, a Scotsman who had been associated with the Trade Union movement for many years, it was too late. Ballinger was accompanied by Winifred Holtby, a writer, ardent feminist, socialist and pacifist and a staunch campaigner for the unionisation of black workers in South Africa. She was greatly admired by Fanny.

Besides teaching, Fanny also became involved in the library of the ICU, which Holtby and some other friends of the ICU had organised. It contained hundreds of books, mainly about the Labour movement in Britain and elsewhere. Fanny was dismayed at the indiscriminate lending to members who were not literate in English and at the number of valuable sets of books that went missing.

Between 1935 and 1940, Fanny also taught English to the Africans at a night school associated with the Union of Max Gordon, a good friend of hers whom she held in high esteem. Gordon, a Trotskyite and opponent of the CPSA organised several unions. By 1939, he had eleven unions representing 20 000 workers from the Joint Committee of African Workers. Fanny met him at a meeting of the Workers Party of South Africa. He rented a room in her cottage.

The night school was located in Exploration Buildings (demolished by 1982). Classes were small but those who attended were given an opportunity to acquire reading skills and numeracy. Fanny’s group had basic literacy and were official members of the trade union. She introduced them to the struggle for human rights that had been fought in the UK and in other countries; the stories of slaves, serfs, and workers without political rights, the struggles of the emerging trade unions and their fight for political rights. She organised a “Junior Class” that, she says, were devoted to her. These classes ended in 1940 when Max Gordon was interned for opposing the war and the committee collapsed along with his unions.

Frank Glass; the Jewish Workers’ Club

In January 1927, Fanny married Frank Glass, who for a number of years had been the Secretary of the Tailors’ Union – that is the Bespoke Tailors, because this excluded the Garment Workers. He was a talented speaker and a journalist. They met at the Trade Union Congress in Cape Town, where Fanny was a delegate for the SAWWU. They both continued with their work in the trade union movement after their marriage. Unfortunately, beset by financial problems, their marriage soon floundered.

At first they continued to live in Stewart’s building in Braamfontein in a comfortable flat, taking in a lodger, a Russian immigrant seamstress and milliner in order to make ends meet. After a while they decided to move to a less expensive semi-detached cottage in Van der Merwe Street, where they rented a room to a Scottish immigrant.

About a year into their marriage, Frank was obliged to resign from the union. With the shadow of his resignation also falling on her, Fanny likewise resigned from her Union, the largest section of which was the Sweet Workers’ Union. Even more pressed for cash, the couple were forced to give up their house and move to Pieterson Street to large rooms with a shared bathroom and little privacy.

To bring in some money, Fanny gave English lessons to the Russian Jewish immigrants who were streaming into South Africa at that time. At the same time she was approached by the Jewish Workers’ Club to organise classes, held at the H.O.D. Hall, for the new immigrants. She greatly enjoyed this work. While some members had little education, others were advanced Marxists, well versed in the works of the Russian authors, Dostoevsky, Tolstoy and Gogol, and they were eager and intelligent learners. Her main goal was to teach them to be able to read the English newspapers to understand what was going on around them. She also travelled to Vrededorp twice a week to teach a group of Jewish women who were unable to leave their homes to attend her lessons. Fanny admired the discussion groups and other cultural activities organised by the Club, but never joined as the majority of the members were Communist sympathisers and she was not.

Frank was appointed as a bookkeeper at the ICU to inspect the branches. When this work too came to an end, desperate to earn a living they took over a tearoom in a working class district with several small factories. Fanny did not enjoy this work, and employed her housemaid to work part-time in the tearoom. After a while it became clear that they could not make a living and they closed down the tearoom and moved to a one-bedroom apartment.

Their relationship ended when Frank decided to travel to China, although their divorce only became final in 1960. In China Frank continued his revolutionary work writing under the name of Li Fu-jen. In 1941 he left China and settled in Los Angeles, where he continued his journalistic work on the Left. Fanny remembered standing broken-hearted at Park Station watching him depart.

Fanny now met Joe Moed, a Belgian national, who would become her partner in life as well as in the bookshop, at a meeting of Duncan Burnside, a socialist member of parliament. Joe had previously patronised Solomon’s Bookshop but once he met her began coming to Vanguards. He became a good customer. When war broke out, Joe lost his job when the American steel company he worked for closed its Johannesburg branch. At Fanny’s suggestion, he became her assistant. He was very capable, accurate and well informed. He moved into her house in Hancock Street. “That”, says Fanny, “was the beginning of our ‘more-than-friendship’”.

The Vanguard Bookshop

Besides his journalistic work Frank Glass had also been running a bookshop, named Frank Glass Booksellers. To drum up customers, Fanny would drag a heavy suitcase full of books to potential clients. She was an omnivorous reader - mostly of American books on politics - and subscribed to many American magazines. In contact with publishers in the USA, she had an idea of establishing a depot in South Africa to distribute some of these political writings. They launched the business on a small scale. One of the publications they ordered, The New Masses, that was partly political and partly devoted to art, began attracting growing numbers of subscribers. Then she began to read the London Sunday Times to discover what literature was available. Slowly, the idea of the Vanguard Bookshop was born. When Frank decided to travel to China, Fanny took over the bookshop and renamed it the Vanguard Bookshop for the Vanguard Press (1926-1988), an American left wing publishing house that published an array of books on radical topics including studies of the Soviet Union, socialist theory and politically orientated fiction by a range of writers. The new bookshop opened on 17 April 1931, and on 16 June, Fanny became its director. The shop remained in Hatfield House in Eloff Street for a number of years. As the business grew, they acquired a second space with two doors between the two. For a long time Fanny was forced to struggle on her own, unable to leave the shop from 08h30 to 17h30.

Fanny acquired a reputation as a discerning bookseller. She stocked the European classics, such as Chekhov, Strindberg and Mann and made contact with distinguished publishers who sent her catalogues. She was guided by magazines, such as the aforementioned, New Masses, (1926-1948), the principal cultural organ of the American Left from 1929 onwards. Thus were books that might otherwise never have reached South Africa introduced.

Fanny introduced the books (published as cheaply as possible by Victor Gollancz) of the Left Book Club. She also subscribed to a couple of Soviet newspapers, the Moscow News, an English language newspaper, and ordered small numbers of the Russian language newspapers, Izvestia (Star) and Pravda (Truth), and Novi Mir (The New World) a monthly consisting of literature, literary opinion and some philosophy. The readership was small but some students became devotees. Later Mr Solomon, a Russian Jew who owned Solomon’s Bookshop, also began to stock these books and Fanny stopped her subscriptions as there was not sufficient readership for two suppliers. Apart from distributing these books, Fanny, with a few others, organised a Left Book Club discussion group. They hired a room in the Johannesburg Public Library and held regular meetings. One of the most eloquent and informed speakers was Professor John Gray from Wits University. Fanny often spoke there herself. Her chief opponent was Solly Sachs, Secretary of the Garment Workers’ Union and a Communist. The Left Book Club existed for several years before fading away.

Old photo of the Johannesburg Public Library

One of Fanny’s greatest triumphs was the introduction of James Joyce’s Ulysses into South Africa. They were the only bookseller in the country that stocked it as it had been widely banned. The book had been brought to her by a customer who worked for the State Department in Pretoria. She said that she sat up the whole night and spent several days reading and studying it, concluding that it would sell but in limited numbers. She sold her own first copy for £5. The book was imported from the original publisher - Sylvia Beach, at Shakespeare and Company in Paris.

Fanny also introduced the series known as the Modern Library, which she felt to be better than the Everyman Books series. The latter emphasized old English literature, while Modern Library was devoted to outstanding contemporary writers. No other South African bookseller stocked the Modern Library books.

Her bookshop became well known all over Johannesburg and drew numerous customers to its one room on the second floor of Hatfield House. Many patrons became her ardent supporters. Writes Baruch Hirson: “This was more than a shop – it was a forum for informed political ideas, and also for the latest currents in philosophy, literature and art.”

While most customers were white, the shop attracted black shelvers, some of whom found a niche in journalism in the post-war years in such publications as Drum. One, Todd Matshikiza, wrote the lyrics for the musical show, King Kong, while another, Bloke Modisane, wrote the book, Blame Me on History (published after he managed to leave the country). Fanny employed anti- Apartheid political activists, such as Helen Joseph and Shanti Naidoo, who were banned but allowed to work. She had a Chinese assistant, who was much loved by the public.

In his book Wasteland (Lowry Books, 1987, pp127-8), the travel writer and journalist David Robbins quotes the reminiscences of a former Vanguard employee:

During the war...I got a job in a bookshop, Vanguard, it was called, and it was run by perfectly crazy people - they were Trotskyites actually. Of course during those days we were heavily dependent on imported culture, on books from London and America. When consignments of new books arrived, everyone who was anyone came to browse. The shop stayed open on Saturday afternoons, and it was like a social occasion. I could name you at least fifty top people around today who all had accounts at the Vanguard ... And of course, Vanguard was an important meeting place for Black and White intellectuals. It was probably the only place they could meet in those days.

Fanny was twice invited to lecture to the Johannesburg Public Library staff on books, book selling and libraries. She presented five lectures on children’s literature for CNA booksellers, later published in the journal of the Transvaal Booksellers Association. Fanny believed very strongly that children’s books displaying any form of racial discrimination should be banned and was distressed that Helen Bannerman’s book, Little Black Sambo, that portrayed a southern Indian child in a deprecating light, was available in South Africa.

Von Brandis Street, 1939-1952

When the Hatfield premises finally became too small, Fanny moved to Warwick House at 51 Von Brandis Street. Here, the shop occupied a large ground floor area with two very large windows for displaying books. She acquired the premises through a friend whose family owned it and who wanted her daughter to open a children’s bookshop there. At her suggestion Fanny (who had already been promoting children’s literature, stocking beautiful carefully selected books) moved into the premises together with the daughter. They took a room on the floor above especially for the children’s books, which Fanny helped the young woman to select and organise. The woman’s heart was not in it, however, so after struggling for months, they sold off as many books as possible, absorbed the remainder into the bookshop and closed the upstairs shop altogether.

In Von Brandis Street, Fanny was visited by one of the Lane brothers, founders of Penguin books, who was impressed at finding two titles by the French linguist, Jacques Maurais, as well as several other titles in the Penguin series on her shelves.

Although for a long time Fanny worked on her own she later engaged a man called Schmidt, a diligent worker but one lacking any knowledge of books and literature and whose English was poor. But he learned quickly and soon he became a reader. After Schmidt went off to work for the CNA, she hired a young Australian girl.

However once war broke out her landlord, the real estate and cinema chain mogul I.W. Schlesinger, began to pressurize her to leave as somebody wished to move into the adjoining shop and take over her space as well. Unable to persuade his lawyer to allow her to remain, she approached a Cabinet Minister, who agreed to invoke legislation protecting tenants from being given notice during the war. Although she continued in the premises for quite a while, she realised that once the war was over and new laws put in place she would be given notice again. She thus began to search for new premises.

Joubert Street, 1952-1966

Opposite them was a dilapidated building that the Johannesburg Building Society was looking to restore. It was very near their old premises and the rental was very reasonable. The new shop in the JBS building had a small ground floor entrance section, but was mostly in the basement. Fanny decided to put the children’s books in the ground floor space and to keep the main stock in the basement. They also invested in a neon sign outside the shop to make it more visible from the street.

Since galleries in Johannesburg were costly, a gallery in the basement where artists could exhibit at a nominal fee was arranged. The first to exhibit was the painter, Douglas Portway, at the time relatively unknown. Their next exhibition was by Eduardo Villa, later to become one of South Africa’s premier sculptors. After a while they no longer held exhibitions of original works, but used the space to exhibit their very beautiful books on art and sometimes prints. Says Fanny: “We had simply not managed to make any money, as we could not bring ourselves to charge the artists much”.

In August 1952 Fanny’s partner, Joe Moed, became a director. Avid readers, they had an immense knowledge of books and became expert in tracing them. Fanny would read all the reviews in the British newspapers: The Observer, the London Sunday Times, New Statesman, Encounter, London Magazine. Then they would discuss them and order together.

They had a Bowkers Books-in-Print, as well as Whittakers Almanac, and the whole set of Transition (1961-1976), a unique forum from and about the African world and its diaspora, first founded in Uganda. Books were imported from many countries, and both in type and range, they were unmatched. They subscribed to Film Bulletin, Sight and Sound, Theatre Monthly, and Polemics, a theatre magazine, and also to architectural publications from Brazil, Bulgarian publications about the film industry, magazines on sex and how to explain sex to children. While in the Joubert Street building, they had a visit from Basil Blackwell from Blackwells, the famous bookshop in Oxford, who told them that they were a “Little Blackwells”.

Fanny writes that the shop flourished until the owners of the building were made an offer by American Express, who were very keen because the premises were very near the big hotels, such as the Carlton. The landlords could see that they were obviously more desirable tenants. Fanny and Joe owed R2000 in back rent.

Old postcard of the Carlton Hotel (Braune and Levy Collection)

At that time, the CNA were looking to open a bookshop opposite the university and wanted to buy their shop. They offered to employ Fanny at a salary of R600 a month. However, Fanny and Joe could not possibly accept the offer. Their stock was worth R31 000 and they felt that given time to pay off their back rent, they could easily remain in business.

Commissioner Street, 1966-1974

For months Fanny and Joe scoured the city as far as Braamfontein, looking for new premises with adequate space for their thousands of books. They had accumulated a huge stock and were under-capitalised. Desperate, they settled on a building in Commissioner Street under construction with heaps of sand and rubble outside and still without windows. On the ground floor there was the skeleton of a shop which was to have very large windows. It had numerous additional small rooms where the white and black staff could have tea separately as required by law. It was a good position and not far from their old Joubert Street premises.

With the windows installed, despite the fact that there was no lighting or plumbing, they moved in at the end of December 1966, storing crates of books in the basement. They had to install shelves in a hurry, and sold as much off as possible as they did not have sufficient space. R12 000 was spent on outfitting the store. Sales rose at Christmas but by then they were already in debt. “The move to Commissioner Street was to be the downfall of Vanguard books” Fanny wrote.

It was hoped that the new Carlton Hotel, then nearing completion, would bring an influx of tourists that would improve business. Unfortunately the building was delayed for several years, the street was dead and business was slow. Even when the hotel opened and business improved, the expenses of running a shop on two levels were great. They were forced to employ more staff and found that even highly educated staff did not necessarily know that much about books. Two typists were employed, one to attend to international orders and the other for local, in addition to a bookkeeper and an auditor. Fanny alone managed the subscriptions, a time consuming and onerous task, besides which she was always on call to help the customers, who valued her in-depth knowledge.

Old drawing of the Carlton Centre and Hotel

Then came a slump. People began to spend less money on books. In addition the shop was plagued by theft of money and of books by staff and customers. Fanny felt that to be a socialist and to be a boss was a contradiction in terms. As she put it, “As an employer I should have taken strict measures to stop the continual frivolity amongst my staff, but as a socialist it was difficult to become a tyrannical employer. I did not really want to be a boss and I think that is why I failed”.

The final blow was the increase in the rent that went up to R1400 a month. Moreover, they were asked to sign a lease for five years, at the end of which their monthly rental would be R3000. This was more than their business could stand. As trade declined they began to fall behind in the rent until they owed R4000. In the past their auditorhad issued letters to their customers to help them out and on another occasion they had raised a loan on the cottage that they shared that was almost paid off. But at that time they were not being harassed by their creditors. Their turnover at Christmas had been R31 000 and Fanny felt that they could have continued, had they not been facing a demanding landlord. “The failure of the Vanguard Booksellers rankled in my mind and affected my health” Fanny commented.

After the shop closed down, they were approached by Benny Sachs, brother of Solly, to start a mail order business. They named it the Fanny Klenerman Mail-Order Book Service. They hired a former typist of Vanguard who set about reconstituting a list of all their customers. Sadly, unable to work together with Sachs, they abandoned the business after a short while. The failed mail order business, said Fanny, damaged her reputation.

Conclusion: looking back

In selflessness and dedication, Fanny Klenerman’s contribution to the struggle against Apartheid was no less than any of the other political activists who were driven into exile. She was a trade union organiser and founder of the South African Women Workers’ trade union, and taught English to blacks in night schools organised by the unions. She ran a bookshop that was unmatched in South Africa.

Fanny remembered how it was sometimes impossible to get into their original small shop. Some of the students who had spent many hours in her shop had become world renowned, scientists, architects and writers. She prided herself for having been consulted by such widely-read, intelligent and left inclined academics as historians, Sheridan Johns and Iris Berger. Said Fanny, “People say that no shop has replaced Vanguards – not even Exclusives and others, which are run by staff not informed or widely read. I used to lecture the library staff, and what I would say to them was that no good librarian or person involved with books is able to work without reading widely.

Fanny’s one possible regret was not having made place in her life for having children. At the time she had weighed this up against her desire to organise workers - and she had rejected the idea. She explained that this was not because she didn't love children, but because she realised that working consistently as she had done, she would not have had the time to bring up a child and be a mother. So in retrospect, she felt that this was the right decision.

Fanny Klenerman passed away in 1983, within a year of dictating her life story.

Dr. Veronica Belling is the author of Bibliography of South African Jewry (1997), Yiddish Theatre in South Africa (2008), and the translator of Leibl Feldman's The Jews of Johannesburg (2007) and Yakov Azriel Davidson: His Writings in the Yiddish Newspaper, Der Afrikaner, 1911-1913 (2009).

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.