Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

The article below forms part of Mike Alfred's series on Joburg personalities from the first decade of the 21st century. Click here to view Kathy Munro's fantastic introduction and here to view the series index. The stories were written in 2005/6.

* * *

Melanie Yap is a petite, attractive, Chinese South African. Until recently she lived in an old, beautifully restored house in Kensington. Her partner died, causing her to sell the house and move away from the general area in which she’d been living since birth. Speaking to her for this book made me realize that perhaps it’s not well understood that all the ‘dark’ South Africans suffered the indignities and prohibitions of apartheid; no group was exempt. Yap includes a description of such a life in her story which follows.

Melanie Yap (LinkedIn)

I attended the launch of Melanie Yap’s comprehensive history of the Chinese in South Africa, Colour, Confusion and Concessions, written in collaboration with Dianne Leong Man. A short time thereafter I asked her about her next project? As they say here, she looked at me ‘skeef’ [dismissively, if you like], replying that she had absolutely no intention of undertaking any other similar venture. This is also a story about the agonies of writing a documentary history. We may be thankful for Yap’s dedication, for the discipline and correct behaviour inculcated by her Chinese heritage. Without it there’d be a black hole, an absence, no record of a South African community huddling together behind its own particular ‘bamboo curtain;’ a community stoically prevailing in an uncertain world of racist indignity. Melanie Yap tells her tale:

Book Cover

My family came out to South Africa at the end of the nineteenth Century. I heard stories that my father’s grandfather came to Johannesburg to open a shop, a little trading store. Because at the time, the Chinese had heard tales of the gold rush and like many adventurers from around the world, the people from Canton Province in South China had easy access to the sea. They were very keen to follow the major gold rushes. They were among the first Chinese who went to Australia and California and were obviously the first Chinese who came out here.

When the gold mines imported Chinese labourers to work on the mines, that’s when a large influx of Chinese came in. Among them were a few Cantonese from the South, but the labourers were mainly from the North. They were sent out on contract, specifically tied to coming to South Africa, working and leaving. So the story in the book is not so much about the labourers who came and went, but about the forefathers of those Chinese South Africans who arrived in the nineteenth century.

Old postcard of Chinese miners (A Johannesburg Album)

Chinese South Africans have not up to now been the focus of much serious historical attention. Misconceptions about them are manifold, not least of which is the mistaken belief that the present day community is descended from labourers contracted to work on the Reef gold mines at the turn of the century. Most South African born Chinese are descendants of independent immigrants who arrived in the country from the 1870s onwards. They settled in the Cape, Natal and later the Transvaal, only to discover that being Chinese limited their opportunities and made them outsiders in a land where race drew the dividing line.

My mother was sent out here in the 1930s, just before the outbreak of World War Two. She was sent as a bride in an arranged marriage. Many Chinese men who first came out to South Africa had no means of marrying unless they returned to China to acquire brides. So for many, those who could afford it, arrangements were made in their home villages and brides were sent out. My sixteen year old mother didn’t take too kindly to her new husband. The arranged marriage lasted five or six years, She was used as cheap labour in her in-law’s shop. After she acquired some measure of independence and earned some money, she obtained a divorce and left. I think she showed enormous courage because in a sense she became an outcast. She eventually met and married my father and from there, our family emerged.

I was born in Johannesburg, here at the Marymount. We lived in Doornfontein, always a ‘grey area.’ I grew up here; I’ve spent my whole life here. I went to school just over the hill, Belgravia Convent of the Sacred Heart. My later life has been centred in this part of the world. The story of going to Belgravia Convent is quite interesting.

The Catholic schools were pioneers in enabling the Chinese to gain a good education. The Catholics and the Anglicans opposed the government’s separate schooling laws. From the time all of us were very young, it was inculcated into us that we had to be well behaved, we had to do exceptionally well academically. Your career path was mapped out for you from the time you were in the grades. It was the start of a long haul; you had to get through every class and then go on to university. The message was, that once you had a university degree, you could leave South Africa. As a Doctor or some other professional you could make a good living elsewhere. It was an escape from the racist society.

Looking back now, one realizes that emotional blackmail was very much a part of the fabric of one’s whole upbringing. Everything you did was scrutinized. If you were naughty at school, you weren’t punished more harshly than other kids but somehow it was more public, the humiliation was greater, because you were told you were now jeopardizing the position of every other Chinese in the school. So we had this collective sense of responsibility. We were regarded as hard working, well behaved, don’t-rock-the-boat, law abiding citizens. Of course it had a reverse side. When you did well, every Chinese kid basked in your success.

Through your school career, little things would happen. The nuns were very kind but they did make it clear to you, particularly when you were playing against other schools, or entering a tournament, they were careful not to create incidents. For argument’s sake, a Chinese child could be the best swimmer or the best netball player but sometimes in order to avoid an incident they’d leave the child out of the team. They’d explain it to the child, saying, look, we don’t want to cause a problem. You can play when we play other convents but not against Government schools.

The first time I became directly involved in problems is when I was about to serve on the Johannesburg Junior City Council. I had been appointed Head Girl. A very brave step for the school to take; a Chinese Head Girl at a white school. They were somewhat concerned that this might cause ructions, but the school accepted me. The tradition was that the Head Girl served on the Junior City Council. The principal called me aside and told me that she was going to contact the council and tell them I was Chinese and she hoped it didn’t cause a problem and if it did she’d send the deputy Head Girl. I said, no that’s fine. And there wasn’t a problem, except that I was aware that they had to ask, to ascertain there would be no public humiliation involved.

I was certainly very aware of being Chinese from the time I was very young. One valued the friendships with white kids, but you were always aware that you were different. You took children home and they commented on the differences in your life style; the fact that you ate different food. In many traditional homes you would have had an ancestral altar. We didn’t have that in our home, my parents were pretty modern. From the time we were very young, in the sense that they wanted us to blend well into the society in which we were growing up, they felt it was very important for us to speak the language. So we, in fact, spoke English at home. In many Chinese homes the parents thought it was important for the children to retain a Chinese background. And especially if a grandparent was living there, then they spoke Chinese at home. I learnt to speak English well because we spoke it all the time, but now as an adult I feel I’ve lost a great deal because I didn’t grow up speaking Chinese. It’s very difficult to go back and pick up one’s Chinese language, cultural connections.

We were living in Doornfontein which was considered a grey area and Chinese were allowed to rent houses there. Chinese were not allowed to buy properties in the Transvaal. It was a tenuous existence because landlords tended to exploit people in that they knew you had to have a place to stay and you were prepared to pay any rent they asked. It was very much later that Chinese were allowed to live in Kensington. Being a very middle class suburb, people were worried about the value of their properties going down if Chinese were allowed into the area. The Chinese first moved into Kensington in the late sixties.

Yes, mom and dad wanted me to be a doctor but as one grows up you realize either you have a scientific bent or you don’t. My forte was always language. It was something I enjoyed from a young age. Fortunately I was allowed at school to participate in things like debating competitions and what have you; so language opened up a whole new and different world for me.

There was conflict at the time I was finishing school. My father attempted to bribe me by saying he’d buy me a car if I applied to medical school and I said that I really didn’t think I could do it and I really wouldn’t enjoy it and I’d like to do a BA. But the problem with a BA was that people considered it to be a ‘nothing’ degree, in that it didn’t equip you to go and do a job. And that was my parents’ greatest concern. They thought a BA was almost too luxurious; to go and study English and arty things.

I managed to circumvent that argument when I discovered there was a Journalism degree at Rhodes University in Grahamstown. It suited me in two ways, first of all to move away from home, because as a teenager, one realizes you are too cloistered at home, and secondly I was able to point out that it was a more focused degree. If I qualified with a Journalism degree, I would more than likely get a job. They were very dubious about it but in the end agreed. And I worked very hard to find employment.

Clock Tower at Rhodes University (Wikicommons)

Our professor at the time organized vacation jobs and he managed to arrange a job for me on the Rand Daily Mail [RDM] at the end of my first year. From there I managed to get a bursary from the RDM which paid part of my University expenses and, that assured me of a job on the paper when I graduated. So, mission accomplished type of thing.

You grow up with these antennae. You try not to expose yourself to situations where people might say, we’re not going to let you in here. So you don’t try to go in there. But of course Johannesburg was reasonably cosmopolitan, so we weren’t plagued by the incidents experienced by young people say, in Port Elizabeth. In the 1970s when I went to University in Grahamstown, I learnt that the Chinese community in PE lived in a Chinese Group Area. They were far more restricted in many ways. If say, Chinese kids went to the skating rink the manager would tell them, sorry we don’t allow Chinese here! And then the press would make a big thing about them being turned away. The Chinese in those places encountered much more petty apartheid. At Rhodes, there were very few incidents, but a Chinese girl was chosen as a Rag Queen contestant and there was quite a scene about it. I think that the University authorities approached her parents saying they didn’t want this blown up by the media and asked her to withdraw. I don’t think she ever publicly said so. She cited personal reasons for her withdrawal, but pressure was certainly part of the issue.

When my parents agreed to my going to university in Grahamstown, this brought up a whole lot of issues about which I was not aware. In order to travel by train I had to have a permit issued by the Chinese Consulate General. This permit stated that I was a well behaved, Chinese lady of good social standing and thus may I be given a compartment in the white section of the train. Another Chinese girl had obtained a similar permit and we were put into a coupe at the end of the train reserved for whites. I remember my father going off to the Consulate to get this permit and I remember thinking that now I must be a lady of good social standing. I also had to apply for a permit to go to a white university.

At the University I joined the Chinese Student Society. After several months the Chairman asked me whether I’d reported to the police? I asked, what for? He told me that all Chinese from other provinces must report to the police station or we’d be chucked out. So those of us from outside the Cape duly marched off to the police station to report. Under old legislation, Chinese weren’t able to move freely between provinces. So from being relatively sheltered as a Johannesburg resident, I was introduced to other realities and legalities. As a university student turning eighteen, I became very much more politicized, realizing that other students now had an opportunity to vote, to participate meaningfully in political activities. Typically, my parents had told me not to take part in any student protests or marches for then I’d be thrown out and that would be the end of the career path.

My first year at university was quite an eye opener. It made me very aware of what it means to be Chinese. From there on I developed a strong sense of needing to do something about it; of course within the constraints laid down by my parents and my loyalty to the community which led me to behave safely. I attended all the protest meetings because I needed to know what was happening. But I didn’t march down the street. Rhodes had this wonderful thing. Everyone’d march down High street in their black academic gowns, be arrested by the police and bundled into the vans; part of being a student. But it was part of being a student I was never able to enjoy, much as I wanted to. Perhaps some of our fellow students may have thought we were cowards but others were sensitive enough to realize we didn’t have all the freedoms to do such things.

I wasn’t allowed to participate but I was allowed to study. Three years at university had given me a background. I chose subjects that would enable me to concentrate on areas of politics in which I had become very interested.

And then Journalism enabled me to do things which I couldn’t do as a Chinese person. Working on the Rand Daily Mail was quite an exhilarating experience. It allowed me to see just how things were operating out there. I was very fortunate to work there. I met such a wide range of people. And they were sensitive to the fact that I was Chinese and I think they protected me in terms of my assignments. I thoroughly enjoyed it; it opened up a whole new world: for the first time I met people of all colours. I worked with black journalists. I learnt what it was like to go to Soweto. You had to get a permit for that. One mixed far more freely. What was so exciting was just being in a world which seemed totally removed from the South Africa in which I’d grown up.

A more recent view over Soweto (The Heritage Portal)

When I joined the RDM after graduating, I was put on their cadet course. As part of the course they wanted us to work on a major metropolitan daily, the RDM, on a smaller newspaper, either in Port Elizabeth or Cape Town, and a weekly paper such as the Sunday Times. I spent six months with the RDM and then was sent to PE for six months to work on the Eastern Province Herald. Being sent down to PE, my editor discovered he’d have to find me a place to live. As a Chinese I should basically live in the Chinese Group Area which was twenty kilometers away from the centre, where the paper was situated. So they had to apply for a permit allowing me to have a flat in town. I think they were prepared to take a few chances, because if something happened to me they could make quite a scene about it. Nothing did happen! Then, serving on the Sunday Times with its different style of writing was also very interesting. Altogether it was a wonderful educational experience. I stayed in journalism for six or seven years and then moved off into advertising.

By then I was involved with the Chinese community. As a journalist writing objectively, I could not grind my own political axe. It suited me from a personal point of view; my parents had both died and I had a young sister and brother to bring up. I needed a job which wasn’t quite as erratic as, and better paid than journalism, so I started copywriting.

Regarding the germination of the book, it happened round about that time, in the early eighties. Through my journalism I’d become involved with the different Chinese associations. That was about the time of the Tricameral Parliament. Although a Chinese representative was elected to that Parliament, the community felt strongly that political rights should be extended to all, instead of just to those who were a lighter shade of dark. The Chinese didn’t wish to become a political football. They were often singled out as having received concessions even though they weren’t white. Some saw them being used as the thin edge of the wedge: if you favour the Chinese, where will it end?

I became involved with other like minded Chinese who were politically conscious and who were aware that our situation in SA was unacceptable. We had lost many young professionals to emigration. Many of my generation who became doctors, accountants, engineers, didn’t stay in South Africa. They went where their talents would be better used. Those of us who remained, felt it was up to us to do what we could to help our community. We felt that we’d received a privileged education and we needed to put something back into the community. We resuscitated the long standing Transvaal Chinese Association. A group of us became very involved in rejuvenating the Association which had been associated with Gandhi’s efforts way back in the first decades of the 20th century. We held elections within the local Chinese community saying we want this organization to speak on your behalf.

We wanted to rectify the need to obtain permits; all the niggling things that were affecting the Chinese in obtaining jobs. Many areas of business were closed to the Chinese. If you wanted to open a business you needed a permit. If you wanted to buy a house in a white area, you had to get a permit. So, all these things were making life difficult in the early eighties, and we wished to improve the situation.

We thought it was necessary to heighten the profile of the Chinese community in Johannesburg; to show that we were part of the wider community, that we weren’t foreigners, that we were South Africans. Although we weren’t overtly political in our approach, many of us believed that we were entitled to the same rights as others. We’d been here for three and four generations and we didn’t see ourselves going back to make a future in China. In 1982 we organised a Chinese Week. It was a public exhibition to which we invited the people of Johannesburg so they could learn about Chinese culture and heritage; to show what it meant to be Chinese but also indicate we were South African. We laid on Chinese cooking demonstrations, fashion, martial arts, dancing, music, all the cultural things. And a group of us, interested in the past, put up a photographic exhibition.

When we did this; finding pictures of people who’d come here early in the 20th century, and pictures of the Chinese mine labourers, we realized that to fill it out, we had to provide captions, captions which told a story. And then, we started the research! Gradually we realized that apart from individual recollections, there was no authoritative written history of the Chinese in South Africa. The beginnings of the book were born at that time, in those captions. We wanted to show that the Chinese were involved in many different things: different trades and professions, to get away from the stereotype that all Chinese people were shopkeepers. Those of us who put the photographs together realized that it was necessary to write our own history.

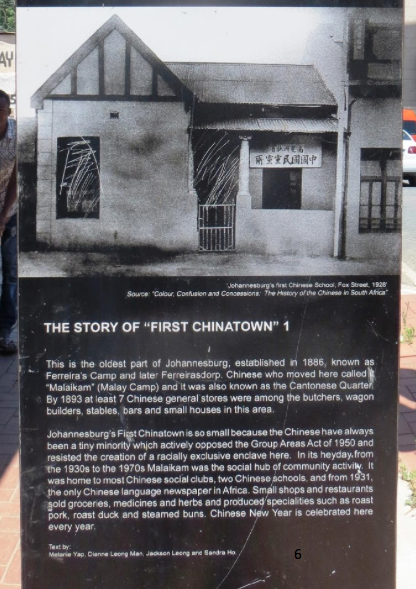

Info board erected by the City of Johannesburg

The historic Transvaal Chinese United Club (The Heritage Portal)

Blue Plaque (The Heritage Portal)

It started as a community project where four or five of us started working on it part time, over weekends, saying let’s find all the old people in the community and ask them to tell us their stories. We’d interview them with tape recorders. We had these huge language problems because many of the older generation didn’t speak enough English and some of us could only speak English. So those of us who could speak Cantonese would ask the questions and then translate for the others and we bumbled along. After three or four years we realized that doing one interview every three or four weeks was not sufficient. We realized that the aim to write a book would never materialize unless someone was prepared to put a substantial amount of work into it.

Three of us embarked upon this project: Dianne Man a librarian at Wits, Lynette Man, an attorney, and me as the journalist writer. We thought, if we pooled our skills we’d be able to put together a sufficiently balanced history of our community. When we sat down to plan the book, we realized that one of us would have to work full time on it. I wasn’t, at that stage of my career, over entranced with advertising and I thought that if we could raise enough money to cover my expenses, I could probably give up my job in order to write the book in two to three years. We wrote a proposal, we went to the community who provided half of what we were looking for, and the Johannesburg City Council provided the balance. But then reality caught up with us.

Imagining that one could work at a certain pace I worked on the assumption I could write so many thousand words a day. None of us was aware of the huge pitfalls that lay in research; how long it would take to find little bits of information and then the amount of cross checking involved. It was a task of such monumental proportions that, looking back on it now and knowing what I know now, I would never have undertaken the job. It was scary! Finding Chinese people in official records was like searching for a needle in a haystack. They were so far and few between. We were doing research in the dark. We might be looking for one Chinese in a time span of fifty years in a little town called Cradock. We didn’t know when we started, that the history of the Chinese went back three hundred and fifty years to the time of Jan Van Riebeeck. We thought Chinese history started around the time of the gold rush.

We kept on finding little bits which sent us off on wild goose chases which often led to more wild goose chases. Somebody would say, Oh you know, our great grandparents told us a story about this Chinese man who lived in Barberton. Then we’d spend days tracking records to find this man in Barberton. We had no way of knowing how the history would evolve. We were working from oral records which only go so far back. Then we realized we had to get all the disciplines right; we had to go to archivists, to librarians and they put us on the right path. We realized that it was far more than interviewing old people and writing a story. But because we aimed to write a documentary account of our community we needed to do the research as well as we could. This meant learning things we knew nothing about: perusing records dating back to the 1660s, and learning High Dutch in the process. We had to go into Chinese records, to find someone who could read Chinese and whose command of English was sufficiently good to translate for us. And also we sought Chinese records on the other side, in China. We had to read widely for little nuggets and snippets.

The whole thing turned into an investigative project, the scope of which we had no conception at the outset. And unfortunately, by starting off in such an ambitious way, we were tied. We had promised the community that we were going to give them a comprehensive record and we had to live up to that promise, no matter how difficult it was and no matter what one had to give up along the way. For instance we ran out of money after five years. We’d made it last longer than planned. But by then, we were all tied in. I realized I couldn’t go and get a job and do the book in my spare time. I had to finish the book first. Instead of taking two or three years as we’d hoped, it took nine years. It took a lot of pain and angst along the way.

The book got written and rewritten and rewritten. Because, as you did more research you had to go back and modify. The first three or four chapters got rewritten half a dozen times. I kept feeling that people weren’t seeing progress. I often wished we could say, OK, stop the research, we aren’t going to dig any more, that’s the history. Then we’d get a letter from China or North America saying , we understand you’re doing this research and I have these family papers which I’ll send you, and suddenly, it would turn a whole section we thought was complete, on its head.

We had all these unrelated, disjointed little bits and pieces that we had to put together. Many people say the book is too long and repetitive. It’s five hundred something pages, and if we’d written everything we’d recorded it would be thousands of pages long. We felt we had a duty to the people whom we’d interviewed, to present their story. We recorded over three hundred interviews. All told, we probably spent a couple of years reading archives and records. In my office stand two six foot cabinets filled with records. We were fortunate that as Chinese we were accepted and trusted with people’s personal recollections.

It was a wonderful thing to have finished but there were many, many times along the way, when I wished I hadn’t embarked upon it.

The work was completed somehow at the right time and it marked the end of an era for the Chinese as it did for all South Africans. The book stops in 1994. At our book launch in 1996, we said we didn’t realize that 1994 was going to happen but the timing was fortuitous in so many ways. From that date the Chinese community changed very dramatically. What was known as the Chinese community changed to such an extent, that it doesn’t exist today. The community we wrote about was a part of the South Africa of the past; a little group that had grown in dribs and drabs via immigration from the 1870s. A community of people who’d settled in a new country, learnt the language, become acculturated, given rise to third and fourth generations of which I am a product. Somebody who can never belong in China because I am South African. I look Chinese but I feel South African.

With the opening up of South Africa there has been a huge influx of Chinese from other parts of the world, new Chinatowns have sprung up, new languages spoken, new cultures from Hong Kong, from Taiwan, from Singapore, from the mainland. The triads have come in, the drug cartels, it’s all been opened up to this sophisticated international influx. Sometimes I feel as foreign as any other South African in the new Chinatowns. In Cyrildene, I see these signs I can’t read and have to ask for menus in English. So, our book marks the end of an era. Whatever else gets written now, will have to take cognizance of the fact that the Chinese community is different.

Entrance to Chinatown in Cyrildene (Mark Straw)

About the author: Mike has spent most of his life in Johannesburg. He earned his living as a human resources practitioner, first in large companies as a manager, [many stimulating years with AECI] and later in his own small HR consultancy. Much of his later occupational time was spent running training courses for managers on how to handle staff within the framework of South African labour legislation, He wrote and published The Manpower Brief, an IR, HR and sociopolitical newsletter, which was popular in many large companies during the 80s and early 90s. A selection of Briefs were incorporated into the book, People Really Matter published by Knowledge Resources. While working, he wrote several business books, one of which, on negotiating, was a sell-out.

In his ‘retirement,’ he has written extensively about Johannesburg, publishing articles mainly in The Star and Sunday Times. Working with Beryl Porter of Walk & Talk Tours, he developed and guided many walking tours around historic Joburg – Braamfontein, Parktown, Newtown, Centre City, Constitution Hill, Kensington & Troyeville, Fordsburg etc. He regularly took visitors to Soweto. His book Johannesburg Portraits – from Lionel Phillips to Sibongile Khumalo, offered popular biographical essays of well known Joburg citizens. His researched paper on Judge FET Krause who surrendered Johannesburg to Field Marshall Roberts during the Anglo-Boer War, was published in the Johannesburg Heritage Journal. The same journal published his series on famous local paleoanthropologists.

Mike is also a widely published poet. Botsotso recently published his third book of poetry, Poetic Licence. His current historical work, published by co-author Peter Delmar of the Parkview Press, The Johannesburg Explorer Book, takes readers on a journey through old Johannesburg, weaving together a history of events and people, which make this city such a fascinating place. His most recent book, a work of journalism, Twelve plus One, featuring transcribed interviews with Johannesburg poets was issued in 2014.

He lived with his wife Cecily, in a century old, renovated house on Langermann Kop, Kensington. A widower since July 2014, he now lives in Eventide Retirement Village in Muizenberg. He believes himself very fortunate in that his son, daughter in law and grandsons live nearby. His daughter lives in Sydney with her husband and son. In case you’re wondering, Luke Alfred, Mike’s son, is the well-known journalist and author.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.